Charles François Gounod (1818 - 1893)

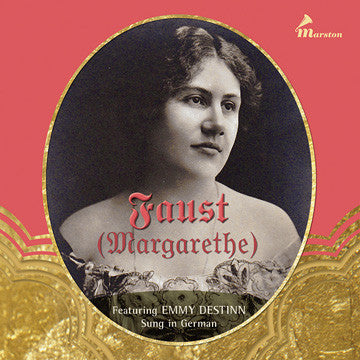

Faust (Margarethe)Featuring Emmy Destinn(Sung in German) Opera in Five Acts Libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré Based on the drama by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Recorded by the German branch of the Gramophone Company, Ltd. on thirty-four sides, February through May 1908 Twenty-two ten-inch sides and twelve twelve-inch sides

| |

| Margarethe | Emmy Destinn |

| Marthe | Ida von Scheele-Müller |

| Siebel | Marie Goetze |

| Faust | Karl Jörn |

| Mephistopheles | Paul Knüpfer |

| Valentin | Desider (Dezsö) Zádor |

| Brander | Arthur Neudahm |

| |

| Chorus of the Court Opera Berlin Grammophon Orchester Berlin Conducted by Bruno Seidler-Winkler | |

Producer: Scott Kessler and Ward Marston

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston and J. Richard Harris

Photographs: Gregor Benko, Harold Bruder, Charles Mintzer, and André Tubeuf

Booklet Notes: Michael Aspinall

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank Andy Moyer for making available his complete set of this recording.

Marston would like to thank Elizabeth Black and Carsten Fischer for editorial advice.

Marston would like to thank Christian Zwarg for discographic assistance.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

CD 1 (69:35) | ||

| 1. | Introduction | 3:53 |

| Orchestra (371 m) 040521 | ||

Act I | ||

| 2. | Rien! en vain j’interroge (Nichts! Umsonst befrage ich der lichten Sterne Chor) | 3:00 |

| Jörn (12596 u) 4-42075 | ||

| 3. | Ah! Paresseuse fille (Ah! Schlummernde Mägdelein) | 2:36 |

| Chorus, Jörn (12597 u) 4-42076 | ||

| 4. | Mais ce Dieu, que peut-il pour moi? (Doch dieser Gott, was vermag er für mein Glück?) | 2:41 |

| Jörn, Knüpfer (12749 u) 2-44366 | ||

| 5. | Et que peux-tu pour moi? (Was vermagst du für mich?) | 3:00 |

| Jörn, Knüpfer (12750 u) 2-44367 | ||

| 6. | Ô merveille (Ha, welch’ Wunder!) | 3:20 |

| Jörn, Knüpfer (12567 u) 2-44368 | ||

Act II | ||

| 7. | Vin ou bière, Bière ou vin (Wein und Bier und Bier und Wein) | 3:23 |

| Chorus (0811 v) 044503 | ||

| 8. | Ô sainte médaille (O heiliges Sinnbild) | 1:43 |

| Goetze, Zádor, Neudahm (12728 u) 2-44369 | ||

| 9. | Avant de quitter ces lieux (Da ich nun verlassen soll) [Valentin’s Prayer] | 3:09 |

| Zádor (12274 u) 4-42077 (transposed down a full tone to D-flat) | ||

| 10. | Allons, amis! point de vaines (Ihr Freunde, kommt! Laßt unmännliche Tränen) | 1:11 |

| Goetze, Zádor, Neudahm (12728 u) 2-44369 | ||

| 11. | Le veau d’or (Ja, das Gold regiert die Welt) | 1:48 |

| Knüpfer (12275 u) 4-42078 (transposed down a full tone to B-flat minor) | ||

| 12. | Merci de ta chanson! (Wir danken für dein Lied) | 4:11 |

| Chorus, Knüpfer, Goetze, Zádor, Neudahm (0808 v) 044081 | ||

| 13. | Ainsi que la brise légère (Leichte Wölkchen sich erheben) | 4:05 |

| Chorus, Destinn, Goetze, Jörn (0794 v) 044082 | ||

Act III | ||

| 14. | Faites-lui mes aveux (Holde Blümlein, o sprecht für mich) [Flower Song] | 3:59 |

| Goetze (0795 v) 043101 | ||

| 15. | Salut! demeure chaste et pure (Gegrüßt sei mir, o heil’ge Stätte) | 4:20 |

| Jörn (530 i) 042163 | ||

| 16. | Il était un roi de Thulé (Es war ein König in Thule) | 3:00 |

| Destinn (12500 u) 2-43095 | ||

| 17. | Ah, je ris (Ha! welch’ Glück) [Jewel Song] | 3:49 |

| Destinn (0806 v) 043102 | ||

| 18. | Prenez mon bras un moment! (Bitte, o nehmt meinen Arm!) | 2:26 |

| Destinn, Jörn, Knüpfer, Scheele-Müller (12568 u) 2-44370 | ||

| 19. | Eh quoi! toujours seule? (Und du bist stets alleine?) | 3:36 |

| Destinn, Jörn, Knüpfer, Scheele-Müller (0781 v) 044083 | ||

| 20. | Retirez-vous (Die Nacht bricht an) | 2:18 |

| Destinn, Jörn, Knüpfer, Scheele-Müller (12731 u) 2-44371 | ||

| 21. | Il se fait tard (Es ist schon spät!) | 2:40 |

| Destinn, Jörn (12509 u) 2-44372 | ||

| 22. | Eternelle! ... ô nuit d‘amour (Ewig dein! ... O Mondschein) | 3:14 |

| Destinn, Jörn (12510 u) 2-44373 | ||

| 23. | Il m‘aime! (Er liebt mich!) | 2:14 |

| Destinn, unknown Faust, unknown Mephistopheles (12501 u) 2-43096 | ||

CD 2 (78:10) | ||

Act IV | ||

Scene 1 | ||

| 1. | Déposons les armes (Legt die Waffen nieder) [Soldiers’ Chorus] | 3:56 |

| Chorus (0810 v) 044504 | ||

| 2. | Allons, Siébel, entrons (Nun, Siebel, kommt) | 2:02 |

| Ottilie Metzger as Siebel; unidentified baritone as Valentin; Eduard Erhard as Mephistopheles (7288 l) 2-44374 | ||

| 3. | Vous qui faites l‘endormie (Scheinst zu schlafen, du im Stübchen) [Serenade] | 2:33 |

| Knüpfer (12276 u) 4-42079 | ||

| 4. | Que voulez-vous, messieurs? (Ihr sollt mir Rede stehn!) | 3:07 |

| Jörn, Knüpfer, Zádor (12507 u) 2-44375 | ||

| 5. | Par ici, mes amis! (Schnell hierher, Nachbarn, kommt!) | 1:53 |

| Destinn, Goetze, Zádor (12569 u) 2-44376 | ||

| 6. | Écoute-moi bien, Marguérite (Hör’ mich jetzt an, Margarethe) [Valentin’s Death] | 4:11 |

| Zádor (0782 v) 042164 | ||

Scene 2 | ||

| 7. | Seineur, daignez permettre (O Herr, so lasse hier niederknien Margarethe) | 2:29 |

| Chorus, Destinn, Knüpfer (12733 u) 2-44377 | ||

| 8. | Dieu! quelle est cette voix (Gott! wie soll ich mich der Gedanken erwehren!) | 3:29 |

| Chorus, Destinn, Knüpfer (12732 u)2-44378 | ||

Act V | ||

| 9. | Va-t’en! Le jour va luire (Geh’ jetzt! Der Tag bricht an) | 3:47 |

| Destinn, Jörn, Knüpfer (0793 v) 044084 | ||

| 10. | Oui, c‘est toi, je t‘aime (Ach, ich dich jetzt umfange) | 4:04 |

| Destinn, Jörn (0809 v) 044085 | ||

| 11. | Alerte! alerte! ou vous êtes perdus! (Auf, eilet! Auf, eilet! Schon naht sich der Morgen) [Final Trio] | 2:15 |

| Destinn, Jörn, Knüpfer (12508 u) 2-44379 | ||

| 12. | Marguérite! (Margarethe!) [Finale] | 2:41 |

| Destinn, Jörn, Knüpfer (12511 u) 2-44380 | ||

Appendix | ||

A Selection of Emmy Destinn recordings, 1906-1909 | ||

| 13. | DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER: Johohoe! … Traft ihr das Schiff im Meere an [Senta’s Ballad] (Wagner) | 4:02 |

| 1906 (G&T 541 i) 043064 | ||

| 14. | LOHENGRIN: Euch Lüften, die mein Klagen (Wagner) | 3:50 |

| 1906 (G&T 4141 h) 43730 | ||

| 15. | LOHENGRIN: Einsam in trüben Tagen (Wagner) | 3:22 |

| 1906 (G&T 538 i) 043070 | ||

| 16. | TANNHÄUSER: Dich, teure Halle, grüß ich wieder (Wagner) | 3:17 |

| 18 October 1909 (HMV 272 ac) 043133 | ||

| 17. | TANNHÄUSER: Allmächt’ge Jungfrau! Hör mein Flehen! (Wagner) | 3:05 |

| 1906 (G&T 4140 h) 43767 | ||

| 18. | MIGNON: Je connais un pauvre enfant (Kam ein armes Kind) [Styrienne] (Thomas) | 2:58 |

| 1908 (HMV 12499 u) 2-43080 | ||

| 19. | IL TROVATORE: D’amor sull’ali rosee (In deines Kerkers tiefe Nacht) (Verdi) | 3:36 |

| 1909 (Odeon xB 4692) 99386 | ||

| 20. | AIDA: O Patria mia (O Vaterland) (Verdi) | 4:20 |

| 1908 (HMV 0800 v) 043095 | ||

| 21. | MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Un bel dì vedremo (Puccini) | 4:07 |

| 1908 (HMV 0801 v) 053371 | ||

| 22. | MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Tu, tu piccolo iddio (Puccini) | 2:23 |

| 1908 (HMV 12753 u) 53533 | ||

| 23. | DALIBOR: Jak je mi (Smetana) | 2:36 |

| 1908 (HMV 12719 u) 73309 | ||

| 24. | HUBICˇKA: Ukolébavka [Cradle song] (Smetana) | 4:08 |

| 1908 (HMV 0805 v) 073007 | ||

Gounod’s Faust

in German

Gounod’s Faust received its first performance in German at Darmstadt in 1861, just two years after its premiere at the Théâtre-Lyrique in Paris. It was billed as Faust in Darmstadt, but for later performances in German-speaking countries the title was changed to Margarete or Margarethe, to distinguish the opera from Goethe’s revered masterpiece, placing emphasis on the soprano heroine rather than the tenor. By the turn of the twentieth century Faust had become one of the most internationally-popular operas, and this 1908 recording was the first attempt to commit the opera to wax, albeit with some fairly major excisions. It was a bold venture for the Berlin branch of the Gramophone Company to record Faust, Carmen, and an all-star Die Fledermaus in 1908 with leading singers of the Berlin Opera. Records were expensive and few people could have afforded a complete Faust on thirty-four sides. It is fascinating to hear a complete opera with a legendary star such as Destinn; would that the London and New York branches had invested in similar generous offerings by Melba, Calvé, or Tetrazzini! Featuring Emmy Destinn as Margarethe, this recording has come to be known as the “Emmy Destinn” Faust.

Emmy Destinn

In 1971 the English magazine the Record Collector published, in Vol. XX Nos. 1 & 2, a detailed biography of this great soprano by Artus Rektorys.

Emílie Veˇnceslava Pavlína Kittlová was born on 26 February 1878 in Prague. As a child she studied not only the violin and piano, but also the guitar, mandolin, and accordion. As her mother had been a professional singer before her marriage, it was no surprise when her daughter Ema’s voice was discovered. She was fourteen when she began a five-year course of study with the mezzo-soprano Maria Loewe-Destinn. Not much is known about Maria Loewe-Destinn’s career, so I was delighted to discover that she had sung at Covent Garden in 1864 in La favorita and Le prophète with the famous German tenor Theodor Wachtel. In No. 1906 of the Athenaeum, 7 May 1864, the feared critic Henry Fothergill Chorley revealed that the teacher did not rank so high among singers as her famous pupil would, forty years later: “Mdlle. Destinn is by no means so good a Fidès as Madame Nantier-Didiée; both ladies having modelled their conception of the part after Madame Viardot’s creation. … Mdlle. Destinn has neither Madame Nantier-Didiée’s range of voice nor her cultivation. The lower notes called for by the music are weak and limited in her case. Her execution is unpolished; her acting is strenuous—too strenuous—yet, in places, it won applause.”

Emílie Kittlová was only fifteen when she was admitted to the acting classes of the Prague National Theater. She also studied German, English, French, and Italian. It must have been devastating for the nineteen year-old soprano, endowed with a very susceptible nervous and artistic temperament, to be rejected at auditions with the Dresden opera house, the National Theater of Prague, and the Theater des Westens, Berlin. However, the director of the Berlin Hofoper heard her, liked her, and offered her a contract. As Bohemian nationals were unpopular in Germany and Austria at that time, Miss Kittlová changed her name to Emmy Destinn, after asking her teacher’s permission. She made her debut on 19 July 1898 as Santuzza in Cavalleria rusticana at the Kroll Opera House, Berlin, to rave reviews. In August 1898 she began to appear regularly at the main Berlin opera house, the Hofoper, where she was a contracted artist until 1909, singing in repertory favorites such as Die Zauberflöte, Don Giovanni, Le nozze di Figaro, Der Frei-schütz, Euryanthe, Les Huguenots, Robert le diable, L‘Africaine, Le Maçon, Le Postillon de Longjumeau, Mignon, Faust, Carmen, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Die Meistersinger, Der fliegende Holländer, Rienzi, Aida, Pagliacci, Prodaná Neveˇsta, Dalibor, Evangelimann, and Madama Butterfly. She also appeared in several Berlin premieres, including Feuersnot, Louise, Salome, and The Queen of Spades. On 14 April 1905 she sang in the world premiere of Leoncavallo’s Der Roland von Berlin, specially commissioned by the Kaiser from his favorite composer.

On the recommendation of the conductor Karl Muck, Cosima Wagner invited Destinn to create Senta in the first Bayreuth performances of Der fliegende Holländer (22 July 1901). Her triumph could not but increase her prestige—and she was only twenty-three years old! She returned in 1902 to repeat her Senta, after which the conductor Felix Mottl invited her to do regular guest performances at Munich. Richard Strauss told her that he had composed Salome with her voice in mind, after having been impressed by her singing in Feuersnot, and was surprised when she initially refused to sing the first Berlin performances of the new opera. In the end she allowed herself to be persuaded, and enjoyed another great triumph (5 December 1906). She sang Salome twelve times in Berlin, with further performances at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris, in 1907. Interestingly, she then dropped Salome from her repertoire, saying that the Strauss roles made her voice too heavy for lighter parts. Strauss wanted her to create Ariadne, but when she made it a condition that there should be a part in the opera for her lover, Dinh Gilly, Strauss explained that there was no role for a star baritone in Ariadne auf Naxos, but offered the couple three performances of Salome at Stuttgart. When Destinn learned that these performances would have to be on three consecutive nights, she turned down the offer; Maria Jeritza created Ariadne.

Destinn sang for the first time in London in 1902 in a series of Wagner concerts conducted by Hans Richter, then on 2 May 1904 she made her Covent Garden debut as Donna Anna, with Suzanne Adams as Donna Elvira, Alice Nielsen as Zerlina, and Maurice Renaud as Don Giovanni, conducted by Richter. Herman Klein described her as “the admirable, nearly perfect Donna Anna, and with no lack of ‚freshness‘ in her round, penetrating tones”. At Covent Garden she sang Aida every season from 1904 to 1914, usually to the Amneris of Louise Kirkby Lunn, and Butterfly every season from 1905 to 1914. Her other popular Covent Garden roles included Senta, Tosca, Nedda, and Valentine. Her lovely Elsa was only heard once. She made a handful of appearances in Andrea Chénier with Caruso, Eugene Onegin with Battistini, Un ballo in maschera, Armide, La Gioconda, Cavalleria rusticana, and d’Erlanger’s Tess. In 1911 and 1912 London heard her Minnie in La fanciulla del West. Despite all her European fame as a veritable “tigress” as Carmen, she managed only two London performances, in 1905, being soon eclipsed by Kirkby Lunn and Maria Gay. She never sang Marguerite in Faust either in London or New York. The London critics loved her, though the Musical Times for 1 July 1910 reports that “The Tosca of the cast was Mlle. Destinn, who has many qualifications for the part. These, it must be admitted, are chiefly vocal, for an histrionically telling interpretation of the character calls for a rather less impersonal style than that with which she favours her British admirers. The best representation of the work was given on June 14, when, with the assistance of Signor Baklanoff, the performance reached a higher level than has ever been attained before in this country.” The reviewer later describes Madama Butterfly: “Mlle Destinn, who can claim to be the original exponent of the part in this country, even though she may have her superiors, was the Cio-Cio-San, and in the latter and more tragic portions of the opera sang with considerable effect.”

Like Lilli Lehmann before her, Destinn heard the siren call of the Metropolitan, but had the greatest difficulty in persuading the management in Berlin to release her for long enough to take part in the New York seasons. Her Met debut finally took place on 16 November 1908, as Aida, with Homer, Caruso, Scotti, and Didur, conducted by Toscanini. She returned every season until 1915–1916. In the pages of the New York Times Richard Aldrich welcomed her: “Mme. Destinn … has a voice of great power, body, and vibrant quality, dramatic in expression, flexible and wholly subservient to her intentions, which are those of a singer of keen musical feeling and intelligence. She showed the possession of strong dramatic gifts. She was a most interesting figure in the performance, and what she did may well have aroused a lively expectation of what she has in store for frequenters of the Opera House this season.” Unfortunately, Destinn found such well-established prime donne as Eames, Gadski, Fremstad, and Farrar rather difficult to dislodge. Farrar, in particular, had almost a monopoly of Tosca and Cio-Cio-San, so Destinn never managed to chalk up as many performances of these Puccini roles as she did in London. On the other hand, she created La fanciulla del West with Caruso and Amato in 1910, singing in a total of twenty-four performances of this work between 1910 and 1914. Of her Minnie, Aldrich wrote: “Mme. Destinn was singularly delicious as Minnie. … She acted the part with great energy and sincerity, and her singing of the music, which is very well adapted to her, was of splendid power and expressiveness.” Her Aida, too, was not seriously challenged (fifty-two performances in the house and on tour!). After the Caruso-Destinn opening night of Aida in 1908, the spectacular soprano-tenor combination was also featured in the opening nights of 1909 (La Gioconda), 1911 (Aida), 1913 (La Gioconda) and 1914 (Un ballo in maschera). Her musicianship made her invaluable to the Metropolitan for revivals of less familiar works, so in her first season she sang in the first American performances of Tiefland, La Wally, and The Bartered Bride, besides appearing as Santuzza, Nedda, Eva in Die Meistersinger, Butterfly, and Mistress Ford in Falstaff. She sang in a gala performance, a miscellaneous concert, and in the Verdi Requiem. This pattern, amounting to about thirty-two performances, would be repeated each season. At the Metropolitan she also sang in Der Freischütz, Germania, Les Huguenots, Lohengrin, The Queen of Spades, Tannhäuser, Il trovatore, Die Zauberflöte, and one performance only as Gerhilde in Die Walküre, one of her Berlin roles. In the 1915–1916 season, after singing only six performances, she hurriedly returned to Europe to be with Dinh Gilly, who could not get to America; the Austrian authorities confined her to her castle for the duration of the war. Considering herself to have been penalized for her Czech-nationalist sympathies, when she returned to New York and London in 1919 she “nationalized” her own (already borrowed) name to Ema Destinová. At Covent Garden, in this her last season, she again appeared as Aida, Amelia, Cio-Cio-San, and Tosca. Although she was rapturously received, her records from this time suggest that her voice, after a “rest” of three years, was no longer quite what it had been. On 8 December 1919 she returned to the Metropolitan for three performances only, in her “own” role of Aida—though now she was sharing it with Claudia Muzio—appearing also as Santuzza. In the 1920–1921 season, her last, she sang Santuzza and Nedda with Caruso once more, Tosca with Gigli, and Verdi’s Requiem, also deigning to sing in one Sunday evening concert, her first since 1908. Over the years she had sung 247 performances with the Metropolitan, in twenty-two roles.

During her great years she made guest appearances in her homeland, singing not only her usual repertoire but also operas by Dvorˇák, Fibich, and Smetana (including Libuše, from which, unfortunately, she recorded nothing). She also appeared in a great number of concerts in Europe and America. The magazine Music and Musicians, published in New York by A. Salmaggi, in its issue of March 1916, lists the program of her recital at the Aeolian Hall, in which she was accompanied by Homer Samuels:

Schubert: Im Abendroth; Die Post; Auf dem Wasser zu singen; Erlkönig

Dvorak: Als die alte Mutter; Zigeunerlied

Kienzl: Frühlingsankunft

Liszt: Die Lorelei; Oh! Quand je dors

Grieg: Ein Traum

Stange: Die Bekehrte

Bohemian songs, and encores including “Vissi d’arte”

Besides all this singing activity, Destinn was a prolific and respected author of novels, essays, plays, and the words and music of songs. She collected not only jewels, cats, dogs, birds, and reptiles, but also books. Mr. Rektorys reports that: “Her taste in literature was odd, although many of the seven thousand books in her library at Stráž were of classical and contemporary authors, the majority comprised such subjects as Alchemy, Astronomy, Black Magic, Necromancy, Witchcraft, Flagellation, Sonnambulism, Spritualism, and the Occult Arts.”

Much has been written about her private life, many gentlemen having “kissed and told,” notably Arthur Rubinstein, who in My Young Years (Knopf, New York 1973) relates that after the last of the 1907 performances of Salome in Paris, for which he had acted as répétiteur, he found himself alone with Destinn in her hotel suite. Although he thought he was doing the right thing in fervently praising her use of rubato, it turned out that she had other things in mind: she let her dressing-gown fall open, revealing a tattoo of a boa constrictor curling round her generously plump leg from the ankle to the thigh! Mr. Rubinstein is kind enough to enthuse about Destinn’s art, which he had already admired in Berlin—in fact, he places her in the same bracket as Caruso, Battistini, and Chaliapin—but he also unchivalrously reveals that in Berlin “she was known for her love affairs with several young music students.” Although she would repeatedly pick artistic or cultivated men to be her lovers—Caruso, Puccini, and Toscanini were all wild about her—only Dinh Gilly seems to have lasted for five years. “Gilly was the only man who really penetrated into the depths of Ema’s being and was able to exercise any influence over her,” according to Mr. Rektorys. In 1923 she married Joseph Halsbach, a Czech Air Force officer who, legend has it, had parachuted into her castle grounds. The marriage was apparently successful. On 28 January 1930 she suffered a stroke, most conveniently while she was being examined by her doctor, and died in hospital later that day.

Destinn’s Singing on Records

Destinn’s place in the operatic hierarchy of her day was so exalted that one longs for her records to be wonderful—some of them are. In 1911 the Gramophone Company (His Master’s Voice) published an attractive illustrated brochure entitled Stars of Grand Opera and Oratorio: the first two pages are dedicated to Melba, followed by Patti, Tetrazzini, Clara Butt, Kirkby Lunn, and then Destinn. After these ladies come Caruso, Battistini, Scotti, Tamagno, Sammarco, Jean de Reszke, and John McCormack. The order of precedence gives us some idea of the importance of the artists to the Covent Garden management and the value of their contracts to HMV. (Calvé and Farrar come next after McCormack—Calvé’s Covent Garden career was over and Farrar never sang there.)

Without subscribing too much to the old system of classifying the soprano voice into such categories as soprano leggero, soprano sfogato, soprano drammatico d’agilità, etc. (Verdi wrote that the “dramatic soprano” did not exist—there was only the soprano), Destinn’s voice might be described as a lyric soprano of enormous volume. The critic Max de Schauensee used to say that the loudest sound he ever heard in an opera house was the union of Destinn’s voice with Caruso’s in La fanciulla del West. Despite the dramatic roles in her repertoire, she does not have the cutting edge to the tone or the well-developed chest register of the traditional “dramatic soprano.” Her superbly trained voice has a fluent emission, a lovely pearly sheen, a warm, pure, silvery, and rounded timbre that appealed to the connoisseurs of London and New York, who accepted her as a worthy successor to Nordica as Aida, Gioconda, Elsa, Valentine, and Leonora (in Il trovatore). She has a complete mastery of her head register, enabling her to take high notes in various different mixtures of registration. Though her soft singing is usually hauntingly beautiful, her floated pianissimi above the stave are sometimes “fixed” and not perfectly in tune. Her legato singing is very finished in her Berlin records, though she does not seem to possess a very long breath span. This is particularly noticeable in the duets from Lohengrin with the tenor Ernst Kraus: both singers scrupulously observe all Wagner’s dynamic and phrasing markings, but it is Kraus who never breaks a phrase with a stolen breath.

Destinn made over two hundred records, so she must have enjoyed the process and the revenue. The results vary from thrilling to disappointing and, sometimes, perplexing. Her first significant group was recorded by Fonotipia in Berlin in early 1905, and among these are some Czech folk songs, very closely recorded, which capture the extraordinary beauty of her voice. Then, if we listen to two arias from Leoncavallo’s Der Roland von Berlin it seems scarcely possible that this is the same singer, for some notes are shrill, some are wobbly, and the high notes have that “fixed” sound that Latin ears cannot tolerate. Interpretation often seems limited to a generalized hysteria, and though many of the sounds are lovely, there is no lack of hooty, acidulous, sour, or unsteady notes, not to mention a curiously “howling” emission of tone. It is somehow typical of her erratic musicianship that, despite all her technical skill, in her Berlin HMV record of “Vissi d‘arte” from Tosca she is unable to execute cleanly the five acciaccature with which Puccini graces the melody. Perhaps her most successful records are those made in Berlin by the Gramophone and Typewriter Company—later the Gramophone Company—between 1906 and 1909, including the complete recordings of Faust and Carmen. Here she often seems to have been placed close to the recording horn, and the technicians caught the fresh, lyrical timbre of the voice and something of the thrilling dramatic sweep of her impassioned numbers, particularly Elisabeth’s Greeting from Tannhäuser and Senta’s Ballad from Der fliegende Holländer. These records triumphantly uphold her great fame, as do the scenes from Butterfly and the “O Vaterland” from Aida. Recordings of the same arias made for the Odeon Company at about the same time are sometimes less satisfactory, though there are some attractive titles including two well-sung and stylistically-appropriate excerpts from Robert le diable. When she began to make her most widely-distributed records, for Victor between 1914 and 1921, her lower-medium tones had become spread, unfocussed, and gummy-sounding, though she retained control of her brilliant high notes. In these Victor records we notice that her voice has become unwieldy: in her only duet record with Caruso, from Il Guarany, she cannot sing quick passages with ease or accuracy. While Scotti, Amato, and Journet, for example, listened to Caruso in their duets with him and did their best to emulate his purity of tone and cello-like legato, Destinn is almost clumsy in comparison with her tenor.

An All-Star Cast for Margarethe

Bruno Seidler-Winkler (1880–1960) was the musical director of the Gramophone Company in Berlin for over thirty years, making hundreds of records both as pianist and conductor. He is an excellent accompanist, and we can be sure that when conducting any orchestral or operatic music he will give us the “traditional” tempi and include plenty of tempo rubato, string and vocal portamento, and other features of contemporary performance practice. The recording of the voices is surprisingly lifelike, with the star singers standing close to the recording horn. Of course, the orchestral accompaniments—sometimes feeble, sometimes raucous—suffer from the usual studio practice of re-orchestration to suit the needs of acoustic recording. The leader must have been playing a Stroh violin, the strings do not nearly balance the woodwind and brass, but never mind! To follow this performance with the score is to learn a lot about how Faust should go (there is no anachronistic metronomic rigor) and to meet with several surprises. Destinn and Jörn, in particular, introduce changes and variants that must belong to a now lost German performing tradition, unknown to singers and audiences at Covent Garden and the Metropolitan, unless Lilli Lehmann and Max Alvary sang the music this way in the uncut German performances at the Met in the 1880s. The many little cuts in this recording are regrettable, but understandable. Sensibly, preludes and intermezzi are generously pruned, but it is irritating to find that the Church Scene has been ruthlessly compressed to fit onto two ten-inch sides: we even lose half of Mephistopheles’s solo “Souviens-toi du passé”. The other unfortunate cut is in the final trio, the last repeat of which, in B major, is reduced to a few bars—but this was stage practice in many theaters.

Although Marguerite was one of the first parts that the young Emmy Destinn studied, she did not sing it so often as Carmen. She demonstrates complete command of all aspects of this complex role, which begins lightly, requiring flawless lyrical singing with some bursts of coloratura in the Jewel Song, and graduates into full-blooded dramatic singing in Marguerite’s last two scenes.

The contralto Marie Goetze was an important enough singer to seriously interfere with the progress and success of Schumann-Heink in her Hamburg days. She was born in Berlin in 1865 and died there in 1922. She studied with Désirée Artôt de Padilla, a favorite pupil of Pauline Viardot-Garcia, and made her debut in 1884 as Azucena at the Kroll Opera House, Berlin. She was a member of the Berlin Hofoper between 1884–1886, and from 1892 to 1920. Her Hamburg engagement was from 1886 to 1890, and in 1891 she sang in Le prophète and Aida in Vienna.

The excellent tenor Karl Jörn was born in Riga in 1873 and made his debut in Freiburg in 1896, as Lionel in Martha. He was engaged at Zürich in 1898–1899, at Hamburg 1899–1902, and from 1902 to 1908 was a member of the Berlin Hofoper company. He sang at Covent Garden in the seasons of 1906, 1907, and 1908, appearing in Das Rheingold and Poldini’s Der Vagabund und die Prinzessin, Der fliegende Holländer, Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor, and Die Meistersinger. From 1908 to 1914 he sang regularly at the Metropolitan, not only in Die Meistersinger, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Das Rheingold, Die Walküre, Siegfried, Parsifal, Der Freischütz, Zar und Zimmermann, Die Zauberflöte, Der Rosenkavalier, Königskinder, and The Bartered Bride, but also in Les Contes d’Hoffmann (with Hempel, Fremstad, Bori, Gilly and Didur), Faust, Cavalleria rusticana (with Destinn), Manon (with Farrar), and Pagliacci. Despite the blandishments of the Kaiser, he would not return to the Hofoper, though in 1914 he sang in the first Berlin performances of Parsifal at the Deutsches Opernhaus. He then returned to America and took American citizenship. He dedicated several years to unsuccessfully trying to market an invention of his for locating mineral deposits, losing all his savings. When Johanna Gadski returned to America with her German Opera Company in 1929 she looked up Jörn and persuaded him to try a comeback. He enjoyed a phenomenal success and added Tristan to his repertoire. He dedicated his last years to teaching in New York and Denver, and died in Denver in 1947. Jörn offers a sound interpretation with moments of distinguished singing.

The famous bass Paul Knüpfer was born in Halle in 1865 and died in Berlin in 1920. He made his debut at Sondershausen in 1884 and was contracted to the Leipzig theater from 1888–1898, after which he spent the rest of his career at the Berlin Hofoper. He was a frequent guest at Bayreuth and, between 1904 and 1914, at Covent Garden, where he sang Gurnemanz in the first local performances of Parsifal, also appearing in Lohengrin, Die Meistersinger, Tannhäuser, Tristan und Isolde, Der Barbier von Bagdad (with Jörn), Der fliegende Holländer, Die Walküre, Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (with Hempel and Jörn), Der Rosenkavalier, and Götterdämmerung. Knüpfer’s performance of Mephistopheles in the complete Faust is that of a charismatic star singer a little past his best. After years of singing at Bayreuth his voice, an important-sounding bass with a wide range, has become somewhat toneless above the bass stave, with intonation problems probably arising from attempting to fix the larynx in a set position. In the medium range his voice has a rich and brilliant tone, and displays the agility in rapid passages, both florid and “patter”, typical of the artist who has had a long experience in buffo parts. He never pushes the tone, and tries to keep the voice light, agile and expressive. He was forty-three at the time of this recording but sounds older: so, too, does thirty-five-year-old Desider Zádor, another victim of the répétiteur Julius Kniese at Bayreuth.

Desider (Dezsö) Zádor was born in 1873 at Horná Krupá in Slovak Hungary, and died in Berlin in 1931. He made his debut in Czernowitz in 1898 as Count Almavia in Le nozze di Figaro. Engagements followed in Elberfeld, Prague, Dresden, and Munich, and from 1906 to 1911 he was a member of the company at the Komische Oper, Berlin, and from 1920–1924 at the Berlin State Opera. His busy career brought him to Dresden (1911–1916), Budapest (1916–1919), and to the United States in 1922–1924. Between 1905 and 1910 he was a regular visitor to Covent Garden, singing Alberich in Das Rheingold, and in Der Barbier von Bagdad, Siegfried, Bastien und Bastienne, Hänsel und Gretel, Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor, and Die Meistersinger. Kutsch and Riemens report that later in his career he mainly sang bass roles. He has a fine voice but faulty technique impedes him from realizing all his good intentions.

The Performance

This particular “Opera at Home” session begins well, with sensitive phrasing of the opening part of the Prelude. Jörn declaims Faust’s opening soliloquy and air with intense dramatic fervor and brilliant tone, though occasionally he sacrifices legato to over-articulation of the words. When he invokes Mephistopheles, up from the depths arises Paul Knüpfer, whose singing, in comparison with Jörn’s more lyrical outpourings, displays all too well the influence of Bayreuth. When they come to the vision of Marguerite at her spinning wheel, “Ô merveille”, Jörn sings the orchestral melody instead of the few phrases of recitative found in the score, rising to a splendid high B natural. His high notes are those of a virtuoso tenor, taken in a mixed voice, always brilliant, and he can swell or diminish them at will. The technique involved is Germanic in style and, to the Latin ear, some of these well-controlled but not always spontaneous acuti will sound squeezed.

After the “Vin ou bière” chorus, neatly and carefully sung, though the gentlemen outnumber the ladies (the contralto part seems to be entrusted to one voice), we hear the recitative and aria of Valentin sung a tone down from score pitch in D-flat by Desider Zádor. (Downward transposition was common in this aria, composed especially for the high voice of Charles Santley.) Zádor is trying to realize all the dramatic possibilities of the scene, but legato and bel canto are missing. His well-trained voice tends towards the fixed sound on high notes and his enunciation of the text could be clearer. It is a relief when Knüpfer comes back in for The Calf of Gold Aria, which he sings quite neatly a tone down from score pitch, with clear articulation and smooth legato in the florid passages. In the second strophe he introduces a few variants. After the Sword Scene comes an abbreviated version of the Waltz and Finale, where Destinn makes her long-awaited appearance, singing with great delicacy and charm. It is not her fault that the famous phrase (that connoisseurs would cross the English Channel to hear Melba sing), “Non, Monsieur! Je ne suis demoiselle, ni belle,” has been musically spoiled by being twisted to fit Goethe’s original lines; the Ballad of the King of Thule has also been musically distorted to fit Goethe’s text, which had been unwisely dragged in by the German translator of the day.

Marie Goetze, although only forty-three years old, sounds weak and hooty in her early recitatives, but makes a good job of the „Flower Song“ in the original key. Her classical training comes out when we hear her introducing appoggiature into Gounod’s music, as if it were by Rossini or Donizetti. (Zádor also does this.) Karl Jörn offers a polished rendering of “Salut! demeure chaste et pure”, with good legato and a splendid, if hardly spontaneous high C; he decorates the aria with a few turns and appoggiature. Destinn’s Ballad of the King of Thule and Jewel Song are both deprived of their recitatives, but although her voice loses focus in the lower passages of the Ballad, she is in fine fettle for the Jewel Song. She is light and brilliant in the opening trill and run, and a sense of humor peeps out now and then. She phrases the aria exactly like the Gounod pupils (Patti, Melba, Eames, and Adams) but also introduces some embellishments unknown to those ladies. The Garden Quartet has been well-rehearsed and is well sung by all, though here again the German text does not properly fit the music. Knüpfer declaims well in the Invocation. The Love Duet suffers from some unfortunate cuts, which, again, may simply reflect stage practice. Both singers perform attractively and eloquently and Jörn finds a lovely head voice piano for “Éternelle!”. In her concluding solo “Il m‘aime!” Destinn sings splendidly in the kind of ecstatic, impulsive music that suits and inspires her, with some soft touches and some thrillingly expansive moments, and a good high C, even though, like many another great singer of the period, she has not yet realized that what is effective on stage cannot always be successfully reproduced on the gramophone.

Act Four begins with a rather gruff Soldiers’ Chorus, but with a few decent tenors audible. Then comes Mephistopheles’s Serenade, which Knüpfer tries to make interesting, including some variants. The Duel Trio suffers from rather jerky singing, and Zádor has some trouble with the high tessitura of Valentin’s Death Scene. In the Church Scene Destinn is at her best and her broad style and vigorous attack must have been thrilling in the theater. In the cadenza, her easy ascent to the high B-natural, with brilliant and unforced tone, is notable indeed.

In the final scene of Act Five Destinn and Jörn are very fine: she phrases “Oui, c’est toi, je t’aime” beautifully, but he is even more touching when he repeats the phrase. I find Destinn’s singing of the reminiscence of the Waltz, “Attends! Voici la rue”, quite memorable in its heartfelt simplicity. Then comes another surprise, for Marguerite sings some softly dreaming phrases, not to be found in my scores, while the orchestra plays the reprise of “Je veux t’aimer”. In the final Trio both Destinn and Jörn are in top form. The last repeat of the melody gains immeasurably (despite the cut) from the conductor’s observing Gounod’s instruction: molto maestoso e grandioso. The last side of the set gives us the apotheosis of Marguerite.

Supplement: An Aria Concert by Emmy Destinn

We have included a few of Emmy Destinn’s Berlin recordings, which show something of the lovely quality of her voice, her temperament, her versatility, and her technical control of her voice before any decline began to set in. On the ten-inch record side there was only room for the first half of Elisabeth’s Prayer from Tannhäuser, which she opens with a clean attack and ascent to the G-flat above the stave on “Allmächt’ge Jungfrau”, grandly imposing without any strain or shouting. This is a lovingly molded performance with warm tone in the middle and lower notes, in which she maintains a flowing legato. Even in the lower passages there is scarcely a hint of the unsteadiness that would later intrude. She introduces some downward portamento to great effect, for example in the phrase “ein weltlich Sehnen”. Her upward portamento is not always so successful: she tends to execute a sort of upward flick or swoop in the general direction of the note she is aiming for, without achieving an unbroken line.

A group of recordings from Lohengrin also finds her at her very best. Elsa’s Dream gives a good impression of her voice, floating dreamily in the first half, ringing out excitedly in the martial declamation of the second. Her very first phrase, “Einsam in trüben Tagen”, is deliciously poised on the breath. Elsa’s song to the breezes, “Euch Lüften, die mein Klagen” is a great record, with a lovely legato and gracefully turned phrasing. Her enunciation of German has nothing of the harshness of Bayreuth: her consonants are clear and limpid, never exaggerated, and she never indulges in a glottal stop. In this record she produces her F, fifth line, in various different mixtures of register; when she sings it pianissimo it is particularly successful, especially on the attack of the last phrase, “In Liebe”. This is virtuoso singing of a high order.

Although she was the first Bayreuth Senta, she does not observe all of Wagner’s piano and pianissimo markings, but her performance of the Ballad remains extraordinarily vivid and varied, giving us some inkling of the impression she must have made in the theater. “Dich teure Halle” is another precious example of the Destinn impact.

A group of Italian arias introduces her in the repertoire that she was mostly to sing in London and New York. “O Vaterland” (“O patria mia”) from Aida, which she would later record in Italian for Victor, is a beautifully dreamy performance, only slightly spoilt by some rather contrived and pinched head notes. Her opening phrase is imaginatively individual, and there is a lot of the authentic Destinn magic in this record. (In “Ritorna vincitor”, on two ten-inch sides, she catches all the varied emotions of Aida and her performance is thrilling. Though she observes all Verdi’s piano markings and is hauntingly lovely in “Numi, pietà”, her emotional involvement with this music causes her to push her chest voice up to F, to force the tone in the middle, and the high B-flat is suspiciously like a scream. From her other popular role of Butterfly she made three records using the 1906 score (the third published version), whereas we are more accustomed to the fourth version (1907). The differences are most marked in the words of “Che tua madre”, where Destinn’s vowels are sometimes naggingly open. Much better is the exquisite attack on the opening phrase of “Un bel dì vedremo”, a performance of much delicacy and charm. All her upper notes from E-flat (fourth space) to the A-flat above the stave are beautifully sung and recorded, though the recording horn could not do justice to her two perfectly placed B-flats at the conclusion. In the final scene of the opera, “Tu, tu, piccolo iddio”, we can feel how awe-inspiring it must have been in the theater to hear her soar up to the high A of “O a me, sceso dal trono”, marked exaltedly by Puccini.

She is rather too solemn for such a playful piece as the “Styrienne” from Mignon and she simply cannot laugh as required, but she does not let us down when she comes to the trill and the high D! She is, naturally enough, most at home in her scenes from Czech operas, and the early ten-inch version of Milada’s aria from Dalibor, sung to the original text, is more exciting than her later German language version. We can hear that her love of her country and her country’s music is sweeping her off her feet, but despite the impulsive tempo and her hell-for-leather approach, her singing is accurate and brilliant, her voice impressive in quality and power from A-sharp below the stave to the high B. In contrast, the lullaby from Hubicˇka is lovingly, caressingly vocalized. It is rather surprising that there should exist so many good performances on record of that particularly demanding aria, “D’amor sull’ali rosee” from Il trovatore, from Siems and Gadski to Raisa, Ponselle, and Arangi-Lombardi, from Turner and Amerighi-Rutili to Callas, Caballé, and Sutherland. Destinn joins the ranks of these virtuose with her stunning performance in German on an Odeon record of 1908, displaying a considerable grounding in the requirements of bel canto: her voice floats on the breath, she has an easy command of high notes (up to the D-flat) both soft and loud, and a clearly defined and elegantly turned trill.

© Michael Aspinall, 2016

The Gramophone Company recorded its first complete operas in 1907. Pagliacci was produced under the direction of Carlo Sabajno, the musical director of the Italian branch of the company, while Die Fledermaus, Die Lustige Witwe, and Ein Walzertraum (Oscar Straus) were entrusted to Bruno Seidler-Winkler of the German branch. Other complete opera recordings followed in 1908 including Leoncavallo’s Chatterton, produced by Sabajno, as well as Bizet’s Carmen and this recording of Gounod’s Faust, both sung in German and directed by Seidler-Winkler. It is puzzling that two French operas of such popularity as Faust and Carmen were undertaken by the German company rather than its French counterpart. Sadly, no correspondence on the planning and recording of these operas exists, and therefore we will likely never know why these two German versions were produced.

This recording was made, as best as can be determined, between February and May of 1908, with all but three sides recorded by HMV’s “recording expert” Charles Scheuplein, who was assigned the matrix number series bearing a suffix “u” for ten-inch sides and “v” for twelve-inch sides. CD 1, Track 1 and CD 2, Track 2, were recorded by “expert” Franz Hampe, whose series bears suffixes “l” and “m” for ten and twelve-inch sides respectively. CD 1, Track 14, Karl Jörn singing “Salut! Demeure” is the only side not recorded specifically for this set. Jörn recorded the aria in March 1906 as a single offering with William Sinkler Darby as “expert”, who used suffixes “h” and “i”. Rather than recording the aria again in 1908, the company used the 1906 recording instead. This set contains another anomaly that needs to be mentioned. Matrix 12728 u appears as both tracks 8 and 10 on CD 1. This is not an error in the listing. This disc comprises the music that comes directly before Valentin’s aria “Avant de quitter ces lieux”, but omits the aria itself and concludes with the music that follows leading up to “Le veau d’or”. Valentin’s aria is recorded separately on matrix 12274 u. In order to keep musical continuity, Matrix 12728 u is divided as tracks 8 and 10 with matrix 12274 u placed in between.

In remastering this performance, we were fortunate to have two sets of original discs, most of which were in usable condition. The only serious challenge was the issue of playback speed, which varies from one session to another. Additionally, many of the discs change speed from beginning to end causing a gradual shift in pitch that needed correcting. As is our customary practice with old recordings, we have removed objectionable surface noise but have tried not to compromise the music with excessive noise reduction.