CD 1 (75:55) | ||

Leopoldo Signoretti, 1840-1915 | ||

ANGLO-ITALIAN COMMERCE COMPANY [DISCO ZONOPHONO] | ||

1902, Milan / With piano | ||

| 1. | LUCREZIA BORGIA: Di pescator ignobile (Donizetti) | 2:21 |

| (10675) 10675 | ||

| 2. | LA FAVORITA: Una vergine, un angiol di Dio (Donizetti) | 2:47 |

| (1171) 1171 | ||

| 3. | LUISA MILLER: Oh! fede negar potessi … Quando le sere al placido (Verdi) | 3:56 |

| (1170-1) 1170 | ||

| 4. | LUISA MILLER: Quando le sere al placido (Verdi) | 3:25 |

| (1170-2) 1170 | ||

| 5. | ERNANI: Tutto ora tace intorno … Solingo, errante, misero (Verdi) | 2:56 |

| (1814) 1814 | ||

| 6. | LA FORZA DEL DESTINO: O tu che in seno agli angeli (Verdi) | 3:29 |

| (1173) 1173 | ||

Giovanni Battista De Negri, 1851-1924 | ||

ANGLO-ITALIAN COMMERCE COMPANY [DISCO ZONOPHONO] | ||

1903, Milan / With piano | ||

| 7. | NORMA: Ah! troppo tardi (Bellini) | 1:54 |

| (1564-1) 1564 | ||

| 8. | NORMA: Ah! troppo tardi (Bellini) | 1:55 |

| (1564-2) 1564 | ||

| 9. | OTELLO: Ora e per sempre addio (Verdi) | 1:27 |

| (1566) 1566, Transposed down a semitone to G | ||

| 10. | OTELLO: Niun mi tema (Verdi) | 2:48 |

| (1561-1) 1561 | ||

| 11. | OTELLO: Niun mi tema (Verdi) | 2:58 |

| (1561-2) 1561 | ||

| 12. | Der Asra (Rubinstein) | 2:27 |

| (1563-1) 1563 | ||

Alfonso Garulli, 1866-1915 | ||

ANGLO-ITALIAN COMMERCE COMPANY [DISCO ZONOPHONO AND PATHÉ] | ||

1903, Milan / With piano | ||

| 13. | LOHENGRIN: Nun sei bedankt, mein lieber Schwan (Mercè, mercè, cigno gentil) (Wagner) | 2:53 |

| Disco Zonophono (1547) 1547 | ||

| 14. | PAGLIACCI: Vesti la giubba (Leoncavallo) | 2:33 |

| Disco Zonophono (1549) 1549, Transposed down a semitone to E-flat Minor | ||

| 15. | MIREILLE: O Magali (Gounod) | 2:59 |

| with Ernestina Bendazzi-Garulli, soprano Disco Zonophono (1548) 1548 | ||

| 16. | DIE MEISTERSINGER: Am stillen Herd (Nel verno al piè) (Wagner) | 2:32 |

| Pathé-AICC (84082) 84082 | ||

| 17. | AIDA: La fatal pietra (Verdi) | 2:38 |

| Pathé-AICC (84086) 84086 | ||

| 18. | MEFISTOFELE: Forma ideal, purissima (Boito) | 2:11 |

| Pathé-AICC (84088) 84088 | ||

| 19. | Aprile (Tosti) | 3:30 |

| Disco Zonophono (1540) 1540 | ||

| 20. | Ideale (Tosti) | 3:09 |

| Disco Zonophono (1545) 1545 | ||

| 21. | \tSerenata (Sera di paradiso) (Composer unknown) | 2:28 |

| with With Ernestina Bendazzi-Garulli, soprano Disco Zonophono (1543) 1543 | ||

| 22. | Ovunque tu (van Westerhout) | 2:47 |

| Disco Zonophono (1542) 1542 | ||

Francesco Signorini, 1860-1927 | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD. | ||

May 1908, Milan / With orchestra, conducted by Carlo Sabajno | ||

| 23. | GUILLAUME TELL: Asile héréditaire (O muto asil) (Rossini) | 3:51 |

| (1493c) 052230 | ||

| 24. | LE PROPHÈTE: Sous les vastes arceaux ... Pour Berthe, moi je soupire (Sotto le vaste arcate ... Sopra Berta, l’amor mio) (Meyerbeer) | 4:02 |

| (1491c) 052229 | ||

| 25. | IL TROVATORE: Ah sì, ben mio (Verdi) | 3:32 |

| (11235b) 2-52669 | ||

| 26. | IL TROVATORE: Se m’ami ancor … Ai nostri monti (Verdi) | 4:26 |

| with Carolina Pietracewska, mezzo-soprano (1486½c) 054210 | ||

CD 2 (75:55) | ||

| 1. | AIDA: Celeste Aida (Verdi) | 3:57 |

| (1478c) 052231 | ||

| 2. | AIDA: Fuggiam gli ardori (Verdi) | 4:21 |

| with Ines De Frate, soprano (1492c) 054213 | ||

| 3. | CHATTERTON: Stanco, spossato, arresta il triste pellegrino! (Leoncavallo) | 3:45 |

| with orchestra conducted by Ruggero Leoncavallo (1469c) 052253 | ||

| 4. | CHATTERTON: Tu sola a me rimani, o Poesia (Leoncavallo) | 2:38 |

| with orchestra conducted by Ruggero Leoncavallo (11210b) 2-52668, Transposed down a semitone to A Minor | ||

Edoardo Garbin, 1865-1943 | ||

GRAMOPHONE & TYPEWRITER, LTD. | ||

November 1902, Milan / With piano, Salvatore Cottone | ||

| 5. | LA FAVORITA: Una vergine, un angiol di Dio (Donizetti) | 2:18 |

| (2843b) 52434 | ||

| 6. | LA TRAVIATA: Un dì felice (Verdi) | 1:55 |

| (2841b) 52428 | ||

| 7. | CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: Intanto amici, qua … Viva il vino spumeggiante [Brindisi] (Mascagni) | 1:54 |

| (2840b) 52433 | ||

| 8. | MANON LESCAUT: Donna non vidi mai (Puccini) | 2:24 |

| (2838b) 52429 | ||

| 9. | MANON LESCAUT: Ah! Non v’avvicinate! … Guardate, pazzo son (Puccini) | 2:18 |

| (2844b) 52430 | ||

| 10. | LA BOHÈME: Aspetti, signorina (Puccini) | 2:59 |

| (2842b) 52431 | ||

| 11. | LA BOHÈME: Mimì è una civetta (Puccini) | 2:54 |

| (2839b) 52432 | ||

GRAMOPHONE & TYPEWRITER, LTD. | ||

1903, Milan / With piano, Salvatore Cottone | ||

| 12. | MANON LESCAUT: Donna non vidi mai (Puccini) | 2:41 |

| (Con586) 052010 | ||

FONOTIPIA | ||

1904-1905, Milan / With piano | ||

| 13. | LA FAVORITA: Una vergine, un angiol di Dio (Donizetti) | 2:41 |

| 21 November 1904; (XPh61) 39029 | ||

| 14. | LA FORZA DEL DESTINO: Solenne in quest’ora (Verdi) | 3:54 |

| with Mario Sammarco, baritone May/June 190;5 (XXPh294) 69015 | ||

| 15. | AIDA: Nume custode e vindice (Verdi) | 4:08 |

| with Oreste Luppi, bass; and chorus May/June 1905; (XXPh91) 69016 | ||

| 16. | MANON: En fermant les yeux (Chiudo gli occhi) (Massenet) | 2:33 |

| 21 November 1904; (XPh59) 39038 | ||

| 17. | CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: O Lola ch’ai di latti la cammisa [Siciliana] (Mascagni) | 2:58 |

| 23 November 1904; (XPh86) 39039 | ||

| 18. | CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: Intanto amici qua … Viva il vino spumeggiante [Brindisi] (Mascagni) | 3:19 |

| with chorus May/June 1905; (XXPh290) 69011 | ||

| 19. | MANON LESCAUT: Donna non vidi mai (Puccini) | 2:35 |

| 21 November 1904; (XPh62) 39116 | ||

| 20. | LA BOHÈME: Addio, dolce svegliare (Puccini) | 4:41 |

| with Adelina Stehle, soprano; Gina Camporelli, mezzo-soprano; and Mario Sammarco, baritone May/June 1905; (XXPh265) 69014 | ||

| 21. | LA BOHÈME: Che penna infame! … O Mimì, tu più non torni (Puccini) | 3:03 |

| with Mario Sammarco, baritone 15 May 1905; (XPh254) 39223 | ||

| 22. | ZAZÀ: È un riso gentil (Leoncavallo) | 1:57 |

| 21 November 1904; (XPh60) 39075 | ||

| 23. | TOSCA: E lucevan le stelle (Puccini) | 2:45 |

| 21 November 1904; (XPh57) 39043 | ||

| 24. | ADRIANA LECOUVREUR: Ma, dunque, è vero? (Cilèa) | 3:03 |

| with Adelina Stehle, soprano 23 November 1904; (XPh95) 39117 | ||

| 25. | ADRIANA LECOUVREUR: Mi basta il tuo perdono … No, più nobile (Cilèa) | 3:21 |

| 21 October 1904; (XPh54) 39036 | ||

| 26. | Sento che t’amo (Fatuo) | 2:27 |

| 21 November 1904; (XPh56) 39065 | ||

CD 3 (78:59) | ||

Fiorello Giraud, 1870-1920 | ||

GRAMOPHONE & TYPEWRITER, LTD. | ||

April 1904, Milan / With piano, Salvatore Cottone | ||

| 1. | TANNHÄUSER: Dir töne Lob! (Sia lode a te!) (Wagner) | 2:37 |

| (2190h) 52047 | ||

| 2. | DIE MEISTERSINGER: Am stillen Herd (Nel verno al piè) (Wagner) | 3:31 |

| (2191h) 52048 | ||

| 3. | DIE MEISTERSINGER: Fanget an! So rief der Lenz in den Wald (Appena il mite aprile) (Wagner) | 3:29 |

| (274i) 052071 | ||

| 4. | CARMEN: La fleur que tu m’avais jetée (Il fior che avevi a me tu dato) (Bizet) | 3:29 |

| (272i) 052069 | ||

| 5. | LUISA MILLER: Quando le sere al placido (Verdi) | 3:29 |

| (273I) 052070 | ||

| 6. | ANDREA CHÉNIER: Come un bel dì di maggio (Giordano) | 2:42 |

| (2188h) 52046 | ||

| 7. | Oblio! (Tosti) | 2:47 |

| (2192h) 52049 | ||

| 8. | Ancora! (Tosti) | 4:04 |

| (271i) 052067 | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD. | ||

1916-1917, Milan / With orchestra | ||

| 9. | Rosa (Tosti) | 3:47 |

| 16 March 1916; (6439ae) 7-52081 | ||

| 10. | Sogno (Tosti) | 2:48 |

| 16 March 1916; (6440ae) 7-52082 | ||

| 11. | Io ricordo, madonna, quella sera (No. 1 from Per Lei) (Tosti) | 3:02 |

| 16 March 1916; (6441ae)7-52084 | ||

| 12. | Invano! (Tosti) | 3:30 |

| 16 March 1916; (6443ae) 052085 | ||

| 13. | Serenata (Toselli) | 2:48 |

| 18 March 1916; (6445ae) 052091 | ||

| 14. | Lungi (Tosti) | 3:12 |

| 18 March 1916; (6446ae) 052088 | ||

| 15. | Primavera (Tosti) | 2:43 |

| 18 March 1916; (6447ae) 052089 | ||

| 16. | Oblio! (Tosti) | 2:57 |

| 1 April 1916; (6488ae) 7-52083 | ||

| 17. | Ave Maria (Grigolata) | 3:27 |

| 1 April 1916; (6489ae) 052090 | ||

| 18. | Non m’ama più (Tosti) | 3:31 |

| 1 April 1916; (6490ae) 052086 | ||

| 19. | JOCELYN: Berceuse (Godard) | 2:48 |

| 18 July 1917 (20092b) 7-252182 | ||

| 20. | Sérénade d’autrefois (Serenata medioevale) (Silvestri) | 3:26 |

| 18 July 1917; (20093 ½ b) 7-52133 | ||

Fernando Valero, 1856-1914 | ||

GRAMOPHONE & TYPEWRITER, LTD. | ||

1903, Milan / With piano, Salvatore Cottone | ||

| 21. | Mattinata (Leoncavallo) | 3:30 |

| (Con672) 052022 | ||

| 22. | RIGOLETTO: La donna è mobile (Verdi) | 2:18 |

| (Con280) 52009 | ||

GRAMOPHONE & TYPEWRITER, LTD. | ||

16 June 1903, London / With piano | ||

| 23. | Dormi pure (Scuderi) | 3:16 |

| (3922b) 52716 | ||

| 24. | CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: O Lola ch’ai di latti la cammisa [Siciliana] (Mascagni) | 2:23 |

| (3924b) 52717, Transposed down a semitone to E Minor | ||

| 25. | CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: Intanto amici qua … Viva il vino spumeggiante [Brindisi] (Mascagni) | 2:04 |

| (3925b) 52718 | ||

| 26. | El amor es la vida (De los Moteros) | 2:28 |

| (3926b) 52719 | ||

| Languages: All tracks on all three CDs are sung in Italian except CD 3, Track 26, which is sung in Spanish. | ||

Producers: Scott Kessler and Ward Marston

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston and J. Richard Harris

Photographs: Ashot Arakelyan; Girvice Archer; Gregor Benko; Harold Bruder; Richard Burch; Flavio Cella; Civico Museo Teatrale “Carlo Schmidl”, Trieste; David Contini and Marco Contini; Richard Copeman; Michael Hardy; Néstor Masckauchán; Charles Mintzer; Miquel Perez; Tully Potter; and Barbara Tancil

Booklet Notes: Michael Aspinall / Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank the following for making their record collections available for the production of this CD release: the late Sir Paul Getty, Lawrence F. Holdridge, Otto Striebel, the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Laurence C. Witten II in the Yale Collection of Historical Sound Recordings, Yale University Library, and John Wolfson.

Marston would like to thank Roberto Marcocci for providing the chronologies for all seven tenors.

Marston would like to thank Elizabeth Black, Rudi van den Bulck, Stephen Clarke, Carsten Fischer, and Christian Zwarg for editorial advice.

Marston would like to thank Richard* and Mary-Jo Warren for their generous financial contribution to this set.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

* Deceased 7 October 2012

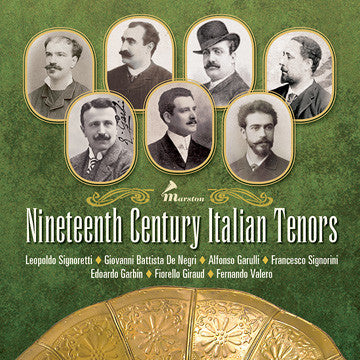

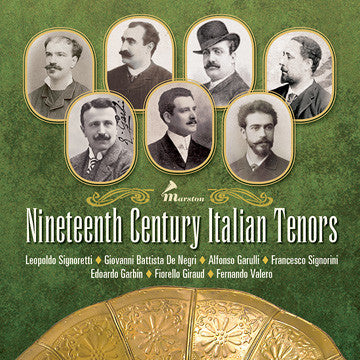

Italian Tenors before Caruso

At about the time that Leopoldo Signoretti made his Zonofono records, the critic Amilcare Lauria dedicated an article to him—“Canto Moderno—Economia e Resistenza” [Modern Singers - Economy and Endurance]—in Le Cronache Musicali Illustrate, Year 1 No. 18, Rome, 20 June 1900:

“One of the last among the survivors of the glorious Italian school of singing, who, the other evening at the Teatro Costanzi, triumphed over his young colleagues, most of whom had weak, tremulous, unsupported voices lacking in everything, especially intelligence … in the opening movement of the dangerous Finale to Act One, Leopoldo Signoretti, though no longer young, proved himself such a great artist that every evening he had to encore O figlia mia diletta. And now, reflecting on all the accomplishment revealed by the Signoretti of today in L’ebrea, you will understand what I mean by miracles of endurance based on economy of voice, which no one possesses and applies as he does! ... After considering a great artist in his artistic sunset: a splendid, rose-coloured and protracted sunset, now we introduce the dawning artist, the blazing dawn of Enrico Caruso. In only two years this Neapolitan artist has taken the first place among today’s young tenors. Just like Caruso today, when Signoretti was young he must have sung well; you can be sure of this, because otherwise we would not still be able to admire his art. If he continues with the same method, Enrico Caruso will be such another in thirty, or forty years’ time. … When I heard Caruso for the first time—in Iris—I was agreeably surprised by the sweetness of his timbre, and … after the Serenata … I thought that Enrico Caruso possessed all the finest qualities of a voice of moderate volume. I was wrong! In the second act finale, when Osaka’s erotic fever erupts, his voice doubled, quadrupled in volume, and the sonorous fullness of his magnificent high notes filled the theatre. … Now, are there other examples of artists who are able to “reduce” their voices as Caruso can? Do any tenori di forza exist who can offer, as he does, all the attributes of a tenore di grazia, deluding you into thinking that they would not be able to make the change from one style to the other, and then doing just that? In the old days there were such great Italian singers, and now there is Caruso, an artist who controls his own voice, restraining its volume, its force, its robustness, using the method of ‘vocal economy’ without your being able to explain to yourself how he does it.”

Lauria’s is one of the earliest rave reviews we have of a Caruso performance written by a distinguished critic, long before he had made his first gramophone records or sung at Covent Garden or the Metropolitan. It is fascinating that Lauria should place him in the same category as Signoretti, an accomplished tenore di mezzo carattere of the “good old school”, whereas other critics described him as “a modern tenor for the modern operas” without glimpsing the technical virtuosity praised by Lauria. We know, alas, that only twenty-one years later Caruso would have been gathered to his forbears, and that, in any case, his artistic development would not echo that of Signoretti. Where Signoretti continued to develop his repertoire with the passage of time, he would almost certainly, in his daily practice, have endeavoured to preserve his voice, technique, and style as they had always been (the line pursued in our time by Alfredo Kraus); Caruso allowed his phenomenal powers to develop to an extent that Amilcare Lauria could not have anticipated. Nor could anyone in 1900 have anticipated the influence that Caruso would exert over tenor singing in general: as Michael Scott has written, nobody today sounds like Hermann Jadlowker, Edmond Clément, or Dmitri Smirnoff, all Caruso’s contemporaries at the Met, but there are still many who take Caruso’s records as their model.

Among Caruso’s great Italian predecessors only Francesco Tamagno (1850-1905), Francesco Marconi (1853-1916), and Fernando De Lucia (1860-1921) left an extensive recorded legacy. For this collection we have gathered together the few, very rare examples recorded by seven celebrated tenors, one of whom, Valero, was Spanish, but, like his predecessor and model Gayarre, enjoyed great popularity in Italy. Very loosely speaking, we can point out that Signorini, Signoretti, De Negri, Garulli, and Valero did not employ an insistent vibrato but, like Marconi and Caruso, tried to preserve a rounded and velvety sound, the “Cremona tone” praised by the critic Lord Mount Edgcumbe (in Musical Reminiscences of an Old Amateur, London, W. Clarke, 1827). Giraud and Garbin more resembled the De Lucia school, with an obvious fluttering vibrato.

Leopoldo Signoretti

Life and Career

After hearing Signoretti‘s very impressive singing on the discs he recorded for Zonofono in 1901, when he may have been about sixty years old, it is not surprising to learn that his contemporaries thought highly of him. Like Stagno, Masini, and De Lucia he sang the repertoire of what was then termed the tenore di mezzo carattere: this meant that he could sing everything from Il barbiere di Siviglia, Mosè, and Semiramide to La Gioconda, Gli Ugonotti, L’Africana, and Lohengrin. As if this were not enough, Signoretti became a famous exponent of the role of Eléazar in L’ebrea (La juive). Even in his last season at a major theater, the Teatro Costanzi, Rome, from March to May 1900, he sang Rossini’s Stabat Mater, L’ebrea (with Maria De Macchi as Rachel), L’elisir d’amore (which he sang for the first time on this occasion), Il barbiere di Siviglia (with Barrientos), and Lucia di Lammermoor (with Torresella).

Some mystery surrounds his early years. Roberto Marcocci believes he may have been born in Rome in 1846, but the research of Michael Tinsley has revealed that Signoretti became a member of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia, Rome (probably as a chorister) in 1860, when he was listed as a “professional singer”, so a date of about 1840 seems more likely. His earliest traced appearances were as Elvino in La sonnambula, Almaviva in Il barbiere, Contino in Crispino e la comare, and Fernando in La favorita at the Teatro Municipal, Santiago del Chile in June and July 1870. Then comes a mysterious five-year gap until May 1875, when he turns up at the Teatro de la Opera, Buenos Aires and in Rio De Janeiro, in Un ballo in maschera, Il barbiere, La favorita, and I Capuleti ed i Montecchi. His Rosina, Leonora, and Romeo was the famous mezzo-soprano Marietta Biancolini, with whom he also appeared in La Cenerentola in Rio. We find him at San Paolo in March and April 1876 for Almaviva again, and Poliuto; he must have sung other roles and in other towns while he was in South America. In September 1876 we find his first documented performances in Italy, at Cingoli in Diana di Chaverny by Filippo Sangiorgi; the same cast repeated the opera in Genoa, Iesi, and Nice. In October and November 1876 he sang Il barbiere and Un ballo in maschera at the Teatro Paganini, Genoa. On 20 May 1877 he created the role of Ascanio in Benvenuto Cellini (Emilio Bozzano). In this last and other operas in this part of his career he was sometimes joined by a certain Adelaide Ollandini Signoretti—his wife, perhaps? In the 1880s we often find Amina Signoretti in the cast with him—a daughter?

Highlights of his long career include a season in Nice in 1877-1878, in which he sang La favorita with Victor Maurel, and Faust, with Virginia Ferni Germano and Pauline Lucca alternating as Margherita. From November 1878 until February 1879 he was in Palma de Mallorca, followed by a season in Alicante, including Roberto il diavolo, while in May 1879 he sang Rigoletto in Bilbao with Giuseppe Kaschmann. In August 1879 he sang Dinorah in Perugia with Battistini, and La sonnambula. In August 1880 in Udine he sang Amenofi in Mosè for the first time, repeating it in Conegliano, Florence, and Venice. He sang Attila in Genoa in 1880, Luisa Miller at Padua in 1880 (and subsequently at the Teatro Apollo, Rome, in 1888 with Elena Boronat, at Teatro Nazionale, Rome, in 1896 with De Macchi, at Pergola, Florence in 1897, and at Storchi, Modena in 1899), I due Foscari in Adria in 1896, and Teatro Rossini, Venice in 1897.

In February 1880 he sang Il barbiere and La traviata with Adelina Patti at the Théâtre de la Gaîté, Paris, and in October Lucia di Lammermoor with Emma Nevada at the Politeama Rossetti, Trieste.

1881 brought seasons in Havana and Porto. Back in Nice in 1882 Medea Mei sang Maddalena to his Duke in Rigoletto. Then he sang with Giuseppina Pasqua in Berlin and Warsaw, followed by a Seville season with Josephine de Reszke, Fanny Torresella, and Francesco Navarini. A summer season in Aix-les-Bains included Bottesini’s Ero e Leandro. In 1883 he sang L’Africana with Elena Theodorini and his first Lohengrin at the Liceu, Barcelona, followed by La Gioconda, La traviata, and Lucia di Lammermoor at the San Carlo, Naples. In the early months of 1884 he returned to Seville, singing La traviata and Faust with Battistini, alternating with performances at the Théâtre-Italien, Paris with Edouard de Reszke, Emma Nevada, and Félia Litvinne. From November 1884 he enjoyed his first season at the Teatro Real, Madrid, culminating in Lucia di Lammermoor with Sembrich and Battistini. From May to October 1885 he was in Montevideo and Buenos Aires with Eva Tetrazzini as the company’s star: they sang in Semiramide with Vittoria Falconis as Arsace and Delfino Menotti as Assur. In 1886 came his first performances as Eléazar in L’ebrea (La juive) at the Costanzi, Rome; he repeated the role in Verona and Madrid, also at the Teatro Argentina, Rome in 1887, at the Teatro Dal Verme, Milan in 1891, the Politeama, Palermo in 1892, the Teatro Coccia, Novara in 1895, and the Politeama Giacosa, Naples in 1900. His last appearances as Eléazar seem to have been at the Teatro Verdi, Salerno in 1901, followed by performances of Gli Ugonotti.

In January 1887 he appeared at the Teatro Apollo, Rome in Luisa Miller, La favorita, and as Erik in L’olandese Volante (Der fliegende Holländer) (in which Elena Boronat and Jules Devoyod were called upon to encore their duet—the Overture was also encored). In between performances he sang La dannazione di Faust by Berlioz at the Teatro Argentina. He returned to Madrid in October 1887 and, despite competition from the galaxy of Marconi, Stagno, De Lucia, and Tamagno, managed to sing La Gioconda, L’ebrea (La juive) (with De Lucia as Leopoldo), Pacini’s Saffo with Eva Tetrazzini and Guerrina Fabbri, and Un ballo in maschera. In January 1889 he sang Lohengrin in Barcelona with Gemma Bellincioni as Elsa. In January 1892 he sang in Lucia di Lammermoor and La traviata with Nellie Melba at the Politeama, Palermo, followed later in the year by a season in Odessa. He sang Lucia di Lammermoor with Luisa Tetrazzini at the Teatro Malibran, Venice, in August 1896 and at the Teatro Apollo, Lugano, in September 1901. Tours in later years took him to Rosario de Santa Fe (Argentina), Porto, Marseilles, Helsinki, and Rostov-on-Don. His last public appearances seem to have been in L’Africana at the Teatro Adriano, Rome in June 1901, followed by a concert at the Teatro Sociale, Monza in July. He retired to Milan and dedicated himself to teaching, dying there in 1915.

Repertoire

Signoretti’s repertoire included: Marina (Arrieta), I puritani, La sonnambula, La dannazione di Faust, Carmen, Mefistofele, Ero e Leandro (Bottesini), La Dolores (Bretón), La favorita, Linda di Chamounix, Lucia di Lammermoor, Maria di Rohan, Fosca (Gomes), L’ebrea (La juive), Ruy Blas (Marchetti), Cavalleria rusticana, Roberto il diavolo, Gli Ugonotti, Dinorah, L’Africana, Saffo (Pacini), La Gioconda and I Lituani (Ponchielli), Il barbiere di Siviglia, Mosè, Semiramide, Aida, Attila, Un ballo in maschera, Don Carlo, I due Foscari, Ernani, La forza del destino, I lombardi, Luisa Miller, Rigoletto, La traviata, Il trovatore, L’olandese Volante (Der fliegende Holländer), Lohengrin, and Tannhäuser. He created roles in the premieres of Mancinelli’s Isora di Provenza (Comunale, Bologna, 2 October 1884); Il Principe di Viana by Manuel Fernández Grajal (Madrid, 1885); Don Cesare di Bazan by the baritone Senatore Sparapani (Teatro Manzoni, Milan, 8 September 1886); Janko by Primo Bandini (Teatro Vittorio Emanuele, Turin, 25 November 1897); a double bill of premieres: Editha by Emilio Pizzi and Il veggente by Enrico Marco Bossi, winner of Sonzogno’s one-act opera prize (Milan, Teatro Dal Verme, 4 June 1890).

Among religious works we find him singing Elia by Mendelssohn and L’entrata di Cristo in Gerusalemme by A. Ambrogi.

The Recordings

Signoretti’s record of the recitative “Tutto ora tace d’intorno” and the opening Allegro assai moderato of the trio “Solingo, errante, misero” from Ernani is perhaps the highlight of this collection. It would be difficult to find anywhere a more splendid example of the grandiose and noble style that Verdi hoped singers would bring to his music. The voice is impeccably produced, a lovely voice though not as golden-toned as some, a boyish voice though not that of a young man. Signoretti’s attack is always clean and his vibrato almost imperceptible. The lower and medium tones flow freely without any throatiness, then when he comes to the D, fourth line, he invariably makes the passaggio di registro, and when he reaches F, G, and A the tone becomes of a trumpet-like brilliance. The ringing interpolated high B-flat at “Lascia ch’io libi almeno” worthily crowns a magnificent performance. This voice is always supported on the breath, making it easy for Signoretti to achieve a flawless legato line, even in the upwardly arching phrases Verdi loves to set for his tenors: in these excursions above the stave his tone is unforced and his enunciation of the words impeccably clear. It will be noticed that Signoretti is in better voice in this Ernani excerpt than in the other records, which may all come from a different recording session.

Amilcare Lauria, in the article quoted above, refers to Signoretti’s singing of “Quando le sere al placido” at a concert at the Costanzi: “one of the most dangerous [arias] that Verdi ever wrote: Verdi was the first Italian composer to ask the tenor voice to perform those acrobatic leaps from the low notes to the highest notes, a feature that many rebelled against (I shall never forget those who rose up against ‘O tu che in seno agli angeli’). Signoretti had to repeat ‘Quando le sere al placido’! I never heard anything like it: and I thoroughly enjoyed watching the artistic way in which he resisted the terrible challenge of Verdi’s desperate phrases; the crescendo of despair that crowns the explosion of the high notes. All his subtlety in saving his breath and his forces, all his little cunning tricks for containing his voice in the medium range and letting it out, fresh and brilliant, in the high notes, without the audience ever catching on; all his art in equalizing the passage from the medium to the high notes without any obvious explosions, made up that skill which will always be called ‘economy of voice’.”

There are two alternative takes of “Quando le sere al placido”, one of them including the recitative but only one strophe of the aria. This recitative is magnificently delivered, in tones of fiery disdain, and with a discreet use of portamento di voce where fitting—as on the words “menzongna, tradimento, inganno!”. In the ensuing strophe of the aria, however, all this fervid declamation seems to have slightly tired the voice, which flows more freely in the other take, where Signoretti has omitted the recitative. In these last years of his career Signoretti does not risk much soft singing, and for that we have to go to De Lucia or Pertile in this aria. However, the beautiful poise of the legato in the opening phrase, marked by Verdi appassionatissimo, is a lesson, as is the rounded and heady sound of the words “chiaror d’un ciel stellato” in which Signoretti employs the typical mixed registration with discreetly darkened vowels pertinent to the passaggio. Like Giraud, De Lucia, and Pertile, Signoretti makes a rallentando on the phrase “lo sguardo innamorato” and again at “amo te sol dicea”, where he interpolates a high B-flat, not without obvious effort. Signoretti’s record of “O tu che in seno agli angeli” from La forza del destino is perhaps less a competitive recording of the aria than a master class: he has all the notes, both high and low, and can join them together with an elegant portamento, as in the downward leaps of an octave at the end of the first two lines, on the words “angeli” and “incolume”. Where he disappoints is in the central cantabile section, “Leonora mia, soccorrimi”, where he cannot reproduce the dolce effect requested by the score. (Caruso does this wonderfully without actually singing softly!) The 7-inch Zonofono of “Di pescatore ignobile” from Lucrezia Borgia, an opera he had last sung at Milan and Verona in 1891, is an attractive, if slightly effortful performance reflecting the sound performance practice traditions of Signoretti’s day. The legato is exemplary, the high tessitura sustained with elegance, the little ornaments and changes neat and expressive. Only the ending is slightly disappointing: the interpolated B-flat is forced and the voice sounds perilously near to cracking on the high A of “obbedito”.

Giovanni Battista De Negri

Life and Career

De Negri was born in Alessandria on 30 July 1851. He was working in his father’s business when, one evening, angered by the drunken warblings of some men in a bar, he sang some phrases from Marchetti’s Ruy Blas, which he had been listening to every evening at the local opera house; to his surprise, everyone exclaimed on the beauty of his voice! He studied with a certain Moretti, and then with Carlo Guasco, Verdi’s first tenor for I lombardi, Ernani, and Attila, and also with Luigia Abbadia. De Negri made his debut on 26 December 1876 at the Teatro Sociale, Bergamo, in Diana di Chaverny by Filippo Sangiorgi, followed by Donizetti’s Poliuto. In 1877 he sang Il Conte Verde by Giuseppe Libani and Ruy Blas at the Teatro Nuovo, Verona. From 1878 to 1882 he sang in Zagreb, in Ernani, Lucia di Lammermoor, Lucrezia Borgia, Nabucco, Il trovatore, Gli Ugonotti, La traviata, Norma, Aida, Faust, La forza del destino, Un ballo in maschera, Roberto il diavolo, and created Lizinka by Ivan Zajc, which he sang in Croatian. In Zagreb he met and married the Countess Fanny Scotti; their daughter Margot also sang. In 1881 he sang in Budapest and Prague. In September 1882 he sang Petrella’s Jone, and both Il trovatore and Norma, with Marie Wilt, at the Politeama Rossetti, Trieste, after which he went to the Teatro Vittorio Emanuele, Messina for Il profeta, followed by L’Africana, La favorita, and others. In 1883 he was heard at the Teatro del Principe Alfonso, Madrid. He began 1884 at the San Carlo, Naples, with Lucrezia Borgia and La traviata and later sang Il profeta, La Gioconda, and Simon Boccanegra at La Fenice, Venice. In April 1885 he was heard in Lucrezia Borgia (with Theodorini), Rigoletto (with Ella Russell), and La traviata (with Theodorini and Mariano Padilla) at the Carltheater, Vienna. In Turin (1885-1886) he sang L’ebrea (La juive) and Il duca d’Alba. He spent the summer and autumn of 1886 at the Teatr Wielki Theater, Warsaw, and went on to Barcelona in November 1886 for Aida, La forza del destino, Il franco cacciatore (Der Freischütz), and Tannhãuser. In December 1887 he scored a definitive triumph at the Teatro Regio, Turin, with twenty-four performances of Otello, alternating with twelve of Aida. He repeated Otello in Fermo, Treviso, Genoa, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo (with Battistini), Trieste, Turin again (1889), Saint Petersburg, La Fenice, La Scala, Alessandria, Fiume, the Costanzi, (with Darclée), and for the very last time, in Turin in February 1894 with Febea Strakosch and Ramon Blanchart.

In 1888 he had another long season in Warsaw and in 1889 others in Buenos Aires and Montevideo. In November and December 1890 he was in Saint Petersburg for a short season. He appeared at La Scala in January 1890 in Simon Boccanegra with Battistini, followed in February 1891 by the premiere of Condor by Gomes. He opened the 1891-1892 Scala season with Tannhäuser with Darclée and Scheidemantel on 29 December 1891, followed by ten performances of Otello with Teresa Arkel and Victor Maurel. On 26 December 1893 he sang his first Siegmund in La Walkiria with Ada Adini, Margaret Macintyre, Juan Luria, and Vittorio Arimondi. His last performances at La Scala were in Guglielmo Ratcliff in February 1895 with Adelina Stehle and Giuseppe Pacini, Sansone e Dalila with Félia Litvinne in January 1896, followed by six more performances of Guglielmo Ratcliff in February. On 23 September 1894, at the Teatro Faà, Canelli, he created L’assedio di Canelli by Delfino Thermignon, then, on 15 November 1894, sang one performance of Tannhäuser at the Teatro Real, Madrid. He returned to Genoa in 1895-1896 for Tannhäuser and Guglielmo Ratcliff. According to Schmidl’s dictionary of music, it was in 1896 that “a cruel malady obliged him to undergo several operations, which robbed him of a large part of his splendid gifts …”. His career was over after only twenty years; he gave “Farewell Performances” of Tannhäuser and Sansone e Dalila at the Teatro Comunale, Trieste. He died at Nizza Monferrato on 3 April 1924.

Repertoire

De Negri’s repertoire included: Norma, Il duca d’Alba, La favorita, Lucia di Lammermoor, Lucrezia Borgia, Maria di Rohan, Poliuto, Condor, Faust, L’ebrea, Ruy Blas, Cavalleria rusticana, Guglielmo Ratcliff, L’Africana, Il profeta, Roberto il diavolo, Gli Ugonotti, Jone (Petrella), La Gioconda, Sansone e Dalila, Aida, Un ballo in maschera, Ernani, La forza del destino, Nabucco, Otello, Simon Boccanegra, La traviata, Il trovatore, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, La Walkiria, Il franco cacciatore (Der Freischütz).

The Recordings

De Negri was no longer singing in public when he made his handful of records, his voice now rather tremulous and unreliable. His choice of repertoire is odd, but presumably all the pieces had some special meaning for him. The voice, however damaged, is still agreeable in tone and without an intrusive vibrato, and his manner of singing is aristocratic and distinguished. De Negri has preserved his technique of joining the registers, as we can hear when, in the passage from Norma, he lifts his voice effortlessly from B-natural to the G above the stave at “Sublime donna”. This fragment of Bellini is not sung with meticulous fidelity to the score, but, as often happens with singers of his generation, his changes are slight but musically meaningful, and command our attention. We note several effective examples of rubato and an interpolated high A in the penultimate bar that modern tenors might well adopt. His “sarà ch’io t’amo” is touching, especially in the second take. There is an attempt at colorful interpretation in Rubinstein’s once popular song “Der Asra”. What we are waiting for, of course, are the two selections from Otello, in which, according to Verdi, he sang some passages—especially the love duet in Act I—better than Tamagno. De Negri is generally more observant of note values than Tamagno and has a warmer voice, with a velvety rather than a brazen quality; although the velvet is wearing thin in patches, the higher notes—like the G on “Oh! Gloria!”—are still brilliant. When he sings more softly, as in “E tu…come sei pallida!” he can still call upon some lovely covered tone on his C-sharp and D. The interpretation, especially on the second take, is quite vivid in a more “gentlemanly” manner than Tamagno’s. Although he has transposed the aria a semitone down and is unable to sustain all the notes for their full length, his performance of “Ora e per sempre addio sante memorie” is surpringly effective. From an obituary notice by the impresario Gino Monaldi, published in Musica e Scena, we learn that De Negri, after his retirement, sang this aria in a benefit concert and was forced to encore it twice—“A thing”, said the astonished tenor, “that never happened to me before!”

Alfonso Garulli

Life and Career

Alfonso Garulli was born in Bologna on 2 December 1856 and died there on 28 May 1915. While working as a bank clerk he studied with Alessandro Busi at the Liceo Musicale, Bologna. He began his singing career in operetta, and made his operatic debut at the Teatro Municipale, Reggio Emilia, in the comprimario part of Lisimaco in Pacini’s Saffo in February 1881, followed by some performances as El Dancairo in Carmen at the Regio, Torino. In April 1882 he appeared at the Teatro Alighieri, Ravenna as Rambaldo in Roberto il diavolo and in La traviata—maybe as Alfredo, because he sang that role in Treviso in November, and at the Filarmonico, Verona in January 1883, where he also sang in Macbeth. In February 1884, at the Teatro Argentina, Rome, he sang Mignon, which he repeated at the Teatro Manzoni, Milan, adding Carmen, Anna e Gualberto by Luigi Mapelli, and La fata del Nord by E. Zoelli. In January 1885, he arrived at La Fenice, Venice, alternating with De Negri in La Gioconda, and after various performances of Carmen not only in the provinces but also at the San Carlo, Naples (January 1885) he managed to get himself engaged at Covent Garden, where he sang one performance of Don José in July to the disappointing Carmen of Patti. He managed slightly better when he was summoned again by Mapleson to London for the 1887 season for four performances of I pescatori di perle. In April, May, and June 1885 he was at the Carcano, Milan, where he sang with his future wife, Ernestina Bendazzi Secchi, in Samara’s Flora Mirabilis, Carmen, and Mireille. They would repeat Flora mirabilis in Rome (Teatro Argentina, 1886), Turin (Regio, 1889), and Treviso. In Italy, Spain, and Poland they sang together in I pescatori di perle, Il franco cacciatore (Der Freischütz), Mignon, Faust, Emilio Pizzi’s Guglielmo Ratcliff (Bologna, 1889), Lohengrin, La traviata, Cavalleria rusticana, Pagliacci, Manon, Werther, and Il sogno di Rosetta by Carlo Mussinelli (Lucca, 1901). They last sang together on the stage on 7 September 1904 at the Grand-Cercle, Aix-les-Bains, in the one-act opera Adagio consolante by Pompilio Sudessi.

In January 1887 Garulli sang at La Scala in Flora mirabilis with Emma Calvé, and in April returned for I pescatori di perle with Antonio Magini-Coletti. At the Costanzi, Rome in November 1888 he sang La favorita with Litvinne and Kaschmann, and at the Teatro Argentina in 1890 Le Roi d’Ys with Calvé and Theodorini. In 1892, as part of the Rossini centenary celebrations, he sang Almaviva in Il barbiere di Siviglia at the Teatro Rossini, Pesaro, with Regina Pinkert, Francesco Navarini, and with Antonio Magini-Coletti and Antonio Cotogni alternating as Figaro. In September 1897 he sang Stelio in Smareglia’s La falena with Emma Carelli and Alice Cucini at the Teatro Rossini, Venice, and in November Siegmund in La Walkiria at the Comunale, Bologna.

Important engagements abroad for Garulli included seasons at the Liceu, Barcelona in 1886 and 1892, Nice in 1886 and 1887, Madrid in April 1889, 1895-1896 and 1896-1897, Valencia in 1892 including La jolie fille de Perth, and two Seasons in Lisbon (1898 and 1899-1900). He was in Saint Petersburg in 1894, where he sang Carmen with Calvé and Cotogni, and his only performances of Don Ottavio in Don Giovanni with Olimpia Boronat as Elvira, Marcella Sembrich as Zerlina, and Battistini in the title role. The following year he reappeared in Saint Petersburg in Pagliacci with the dazzling cast of Sembrich, Cotogni (Tonio), and Battistini (Silvio), in Tannhäuser with Battistini and Carmen again, with Calvé.

He seems to have sung his first Canio in Pagliacci, an electrifying interpretation, which brought him new fame, in September 1892 at the Teatro Malibran, Venice, reprising the role later that month at Vienna’s Ausstellungstheater. October brought further performances at the Teatro della Pergola, Florence, the Teatro Nazionale, Rome, and the Dal Verme, Milan; later appearances were in Palermo, Warsaw, Milan (Teatro Lirico), Saint Petersburg, La Coruña, Madrid, Pamplona, and Lisbon. After 1901 Garulli appeared less frequently, his last performances being at the Teatro del Corso, Bologna: Werther in 1907 and Lohengrin in 1911.

Repertoire

Garulli’s repertoire included: Carmen, La jolie fille de Perth, I pescatori di perle, La favorita, Faust, Mireille, Le Roi d’Ys, Pagliacci, Cavalleria rusticana, Manon (Massenet), Werther, Roberto il diavolo, Don Giovanni, La Gioconda, Il barbiere di Siviglia, Flora mirabilis, La falena, Mignon, Macbeth, La traviata, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, La Walkiria, and Il franco cacciatore (Der Freischütz).

The Recordings

In his monumental work Le Grandi Voci (Istituto per la Collaborazione Culturale, Rome 1964) Rodolfo Celletti analyzes Garulli’s voice, technique, and style with enthusiasm; he declares that, despite the technical limitations of his clear lirico-leggero and a restricted range, Garulli “compensated for this by the expert use of the mezzavoce, pianissimo, and when necessary, the falsetto; but among his characteristics were the sweetness and charm of his phrasing and his perfect taste in the use of elegiac shadings.” In lyrical works his singing had a tension and warmth unusual for a light tenor, and in his later years “this sweetest of singers—thanks also to his notable powers of immersing himself in his character—was changed, in Act IV of Carmen or in Pagliacci, into an interpreter who was not only pathetic, but savage, violent, even brutal. But even then his voice still preserved the timbro toccante, fatto di lacrime (touching timbre, made up of tears) praised by the critics.” All of this is confirmed by Garulli’s few recordings, made even though they were in his vocal decline, and we even begin to understand why Celletti should claim that Caruso preferred Garulli to all his tenor contemporaries.

Comparing two very different discs among the Zonofoni, “Ovunque tu” by Niccolò Van Westerhout and “Vesti la giubba” from Pagliacci, we can confirm the soundness of Celletti’s remarks. “Ovunque tu” is a carefully composed salon song (by one of Ricordi’s young hopefuls) that never quite reaches the dignity of a real tune, but which is gratefully written for the voice, giving Garulli an opportunity to demonstrate a beautiful legato style, with model enunciation, rising at the end to an enthusiastic high B-flat. There is considerable charm in this singing, as also in Tosti’s “Ideale” (of which the last phrases are cut.) The familiar aria from Pagliacci comes as something of a shock: have we ever heard it sung quite like this? Leoncavallo marks the aria Adagio; perhaps, on records, only De Lucia sings it as slowly as Garulli. What we hear is almost painfully appropriate to the situation: a tenor, a lirico leggero perhaps in younger days, has suddenly blossomed into a tragic and heroic figure. The opening words are muffled by emotion (the score asks for declamando con dolore—declaiming sorrowfully) only to be followed by an ironic inflexion on “la faccia infarina” (whiten your face with flour). Like De Lucia, at “e rider vuole qua” Garulli ignores the instruction to carry the voice up to the upper G, then reminds us of his training in older operas by his playing with the time effectively at “t’invola Colombina”. Like De Lucia and unlike Caruso, he does not mind snatching a breath between “ridi” and “Pagliaccio” because his sustained singing is well supported, with a very prolonged high A on “infranto”. For the attack on the last phrase, “Ridi del duol”, Garulli finds a unique effect: we suspect we are about to hear a violent explosion of sobbing, but Garulli surprises us with a restrained, but bitterly choked grimace. There is no vulgar outburst of unmusical sobbing. This interpretation rewards study: one has to get used to it.

A brief passage from Lohengrin’s farewell, “Cigno fedel!”, comes as a welcome reminder of how Italian tenors used to bring out all the inherent melody in Wagner’s vocal writing, lovingly sculpting the phrases with a natural feeling for rubato and for the beauty of Salvatore Marchesi’s Italian words. Garulli begins pianissimo with a hauntingly beautiful sound, despite a tendency to tremulousness. His execution of the line “e che il San Graal ti salverà” is truly memorable, a precious, though a brief record. In two duets with his wife, the soprano Ernestina Bendazzi-Garulli, we hear the kind of cultivated duet singing, each voice listening to and blending with the other, so prized in those days. Bendazzi-Garulli, daughter of the more famous Luigia Bendazzi (who created Maria in Simon Boccanegra) seems to sing well, with a strong, vibrant voice, but is perhaps less interesting an artist than her husband.

Francesco Signorini

Life and Career

Signorini was born in Rome in 1860 or 1861. He studied with Ottavio Bartolino and then with Tamberlik. He made his debut in Nabucco at the Politeama Vittorio Emanuele II, Florence, in May 1882, and in 1884 was heard in Faust at the Teatro Grande, Brescia, and in Faust and La forza del destino at the Politeama Umberto, Rome. After Il trovatore at the Teatro Brunetti, Bologna and Poliuto in Brescia in 1885, he went to the Teatro Solis, Montevideo, where he sang in Il trovatore and Norma with Eva Tetrazzini, in La favorita and other operas. In December 1886 he sang Don Carlo at Modena, with Eugenia Mantelli as Eboli. In September 1888 he departed for a season in Lisbon, meeting up with Eva Tetrazzini again, singing with Battistini in Faust and Ruy Blas, and with Regina Pacini in Lucia. In Alessandria, in November 1889, he sang his first Arnoldo in Guglielmo Tell, which he would later sing in La Spezia, Budapest, Fermo, Pesaro, Mexico City, Florence, Matelica, Bari, and Piacenza. He then left for Buenos Aires and Montevideo, where he sang with Patti in Lucia and added Ponchielli’s I Lituani to his repertory. Back in Italy he sang Don Carlo at the Regio, Parma in December 1889 with Adalgisa Gabbi and Giuseppe Kaschmann, followed by Aida with Gabbi and Mario Sammarco and Ernani, in which Kaschmann alternated with Sammarco. In March 1890 he arrived at the Fenice, Venice, with Faust and Serenata Veneziana by A. Alfred Piatti.. He returned to La Fenice in January 1911 for performances of Ernani, his last operatic appearances.

His marriage to a singing teacher, Camilla Botti, resulted in improvements in his singing technique, as was noticed when he sang Cavalleria rusticana at the Teatro Pagliano, Florence, in December 1890, followed by Il trovatore, Lucia di Lammermoor, Le Cid, and Spinelli’s Labilia at the same theater. During an extensive season in Budapest in 1891 he sang Roberto il diavolo for the first time. In February 1892 he sang L’ebrea in Budapest followed in March by Pagliacci. In May 1892 came his first Otello at the Krolloper, Berlin, with De Macchi and Sammarco. In 1893-1894 he enjoyed a season in Bucharest with Sammarco, including his first Lohengrin, and sang Otello with none other than Victor Maurel. During his Bucharest season he darted over to Madrid to sing Lucia in November 1893, and would return to the Teatro Real in 1902-1903 for Aida and Guglielmo Tell. In September and October 1894 he was in Mexico City, alternating with Tamagno in Il trovatore and Gli Ugonotti. The summer of 1896 was spent in Buenos Aires and Montevideo, while the following summer found him in Santiago, Chile. In February 1897 he sang one performance of Don Carlo at La Scala, Milan, after which he enjoyed a long season in Odessa from November 1897 to February 1898, singing with Luisa Tetrazzini in Gli Ugonotti, with Ines De Frate in Aida, Il trovatore, and Otello, with Alice Cucini in Il profeta, and with Sammarco in Andrea Chénier. He sang Gli Ugonotti and Il trovatore at the San Carlo during the 1898-1899 season. (His final return to Naples for one performance of Ernani in 1911 was a flop.) At the Costanzi, Rome, he sang Gli Ugonotti in 1904 and Don Carlo in 1910. In 1900 he created Ivan by the twenty year-old Pasquale La Rotella at the Teatro Piccinni, Bari: “a splendid impersonation by the tenor Signorini, who added to his exquisite art the phenomenal power of his voice, which is absolutely necessary to Maestro La Rotella’s opera.” (Le Cronache Musicali, 1 July 1900.)

During the last decade of his career he was heard in many Italian theaters: the Adriano, Rome; the Regio, Parma; the Comunale, Trieste; the Goldoni, Livorno; and in Florence, Palermo, Padua, and Turin. He also made many appearances abroad in this period, traveling to Prague (1901 and 1902), Alexandria (1903 and 1904), Lisbon (1904 and 1905), Constantinople (1907), and from September until December 1907 he was busy with a touring Italian Opera Company, singing Aida, Pagliacci, Il trovatore, and Otello in Kansas City, Los Angeles, Oakland, San Francisco, St. Louis, and Berkeley. He died in Rome in September 1927.

Repertoire

Signorini’s repertoire included: Noma, I puritani, Carmen, Mefistofele, La favorita, Lucia di Lammermoor, Poliuto, Andrea Chénier, La Regina di Saba (Goldmark), Faust, L’ebrea (La juive), Pagliacci, Ruy Blas, Cavalleria rusticana, Guglielmo Ratcliff, Le Cid, Erodiade, Il profeta, Roberto il diavolo, Gli Ugonotti, I promessi sposi (Petrella), I Lituani (Ponchielli), Guglielmo Tell, Labilia (Spinelli), Aida, Un ballo in maschera, Don Carlo, Ernani, La forza del destino, Otello, La traviata, Il trovatore, I vespri siciliani, and Lohengrin.

The Recordings

Signorini is a typical example of the kind of tenore drammatico who specialized, in the years before the 1914-1918 war, in operas like Gli Ugonotti, L’Africana, Il trovatore, Aida, and Guglielmo Tell. Sheer bulk and volume of tone, with easy and trumpeting high notes, were what audiences eagerly awaited. Refinements, such as the trills and runs that even Verdi sometimes requires of his tenor, were scorned. Signorini’s medium register is pleasantly warm, rather beefy, and free of the throat. When he rises to the F-sharp, top line, he switches disconcertingly into a rather uncomfortable sounding mixed register to produce squeezed high notes that seem to be based on the vowel E. However, the high B-flat is always forthcoming, though sometimes with a slightly strangled sound. On the whole Signorini is rather monotonous in his stodgy outpourings, but there are some moments of considerable distinction. The two excerpts from Il trovatore are appealing. He sings “Ah sì, ben mio, coll’essere” with a good legato, some expressive rubato, and includes a beautiful soft head note on the upper G-flat. He even seems to attempt the two trills: if so, he is the only Italian tenor on record before Bergonzi to include them. He mixes up the words, but that scarcely matters. In the duet “Ai nostri monti” with the excellent Carolina Pietra-cewska he includes some nice touches of soft singing (though by no means observing all of Verdi’s dynamic indications). “O muto asil” from Guglielmo Tell is a rather strenuous performance, lacking the brilliance of tone and skillful management of the softly taken upper G that enabled the elderly Tamagno to make such an effect in this aria. He is unable to follow any of Verdi’s expression marks in “Celeste Aida”, and breathes wherever it suits him. He is better in the duet from Act III, in which Ines De Frate, a favorite soprano drammatico of many record collectors, also has no scruple about breathing in the middle of words. The owner of a fine and fairly well-trained voice, with some lovely head notes, she offers some curiously distorted vowels.

Whereas the label of the record modestly promises only the “Pastorale” from Le prophète, the disc actually begins with the “Racconto”—“Sotto le vaste arcate”, a dramatic recitative in which Jean de Leyde describes a dream in which he sees himself being crowned in a great cathedral, only to fall victim to Satan. The mood changes as he reflects on his love for the village maiden, Berthe, in the “Pastorale”. Signorini must be thanked for having recorded this passage, but he is quite unable to make any contrast between the two sections: each is lustily bawled, to brilliant effect in the bravura passage at the close, with repeated ascents to the high B-flat.

Signorini also participated in a complete recording of Leoncavallo’s Chatterton, sharing the title role with Francisco Granados. He sings particularly well—in his now familiar hefty style—in his first lyrical outpouring in Act I, “Ricomposi l’antica favella”, with a solid line and some nice piano touches. From Act II he sings splendidly and with more than his usual feeling for words and music in the recitative “Stanco, spossato”, with some attractive softer passages, followed by the aria “Tu sola a me rimani, o Poesia”, with a superb upward lift to a ringing climax. In these pieces Leoncavallo’s sinuous and flexible conducting shows how a loving and knowing hand can bring out the expression lurking in a typical Leoncavallo tune. The complete recording can be heard on Marston 52016.

Edoardo Garbin

Life and Career

Garbin was born in Padua on 12 March 1865. Coming from a poor family, he was working as a stable boy when his voice was discovered. After studying with Antonio Selva and Vittorio Orefice (who also taught Pertile), Garbin made his stage debut at the Teatro Comunale, Vicenza, in September 1891 as Alvaro in La forza del destino, which he was to repeat in Conegliano (November 1891), at the Teatro Dal Verme, Milan (January 1892), at the Teatro Regio, Turin (December 1894), and, later on, in Warsaw (in 1898, with Salomea Krushelnytska, Tilde Carotini, and Battistini). He also sang Cavalleria rusticana at the Dal Verme, at the Politeama Genovese and at the San Carlo, Naples (March 1893, with Bellincioni), where he also sang Rigoletto. He then created roles in two important and widely performed operas: Franchetti’s Cristoforo Colombo and Verdi’s Falstaff. The former was first produced at the Carlo Felice, Genoa, in October 1892, with Kaschmann, Antonio Pini-Corsi, Navarini, and Arimondi in the cast, and was repeated at La Scala (December 1892 and March and May 1894). He sang the opera again in Buenos Aires in 1906.

After his success in the first performances of Falstaff (La Scala, February 1893) he repeated his Fenton on a triumphal tour that year with most of the original cast intact (though Victor Maurel as Falstaff was occasionally replaced by Ramon Blanchart or Arturo Pessina): Genoa (April), Rome Costanzi, (April), Trieste, Venice, and Vienna (May), Berlin (June), and Brescia (August). He sang in Falstaff again at the Dal Verme in December 1895, at La Scala in March 1899 (with Angelica Pandolfini, Adelina Stehle, Elisa Bruno, Antonio Scotti, and Rodolfo Angelini Fornari), at the Costanzi, Rome in May 1911 (with Frances Alda, Guerrina Fabbri, and Scotti), and in the Verdi Centenary performances in Busseto (September 1913) with Linda Canetti, Lucrezia Bori, Fabbri, Pasquale Amato, and Fernando Autori, and at La Scala again with largely the Busseto cast (Scotti and Sammarco alternating as Falstaff).

In his lucky year 1893 Garbin met the soprano Adelina Stehle, his future wife, who is said to have had a great influence in perfecting his technique and helping him form an individual style. He added Manon Lescaut to his repertoire, including some performances in Genoa with Cesira Ferrani, the original Manon of Puccini’s opera. In 1894 he dipped into the older repertoire, singing Lucrezia Borgia in Genoa, and in 1895 he sang Lucia di Lammermoor in Turin (with Regina Pinkert) and Trieste. He first sang Massenet’s Manon in 1895 at the Pagliano, Florence, and the Comunale, Trieste, with Gemma Bellincioni, and in Naples with Elisa Frandin; at the Teatro Nazionale, Rome, he divided his attentions between the Manons of Stehle and Rosina Storchio.

Stehle came to share the stage with Garbin for the majority of his performances: they appeared in La bohème in Florence, Lucca, Palermo, Milan, Rome, Madrid, Barcelona, Alexandria, Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Odessa, Padua, and Naples. Other operas in which they sang together included Manon Lescaut, Ero e Leandro, Mefistofele, Fedora, Werther, Adriana Lecouvreur, and Lohengrin. Lesser known works in which they sang include I dispetti amorosi by Gustavo Luporini (Teatro del Giglio, Lucca, September 1894), La cortigiana by Antonio Scontrino (Dal Verme, Milan, January 1896), Maruzza by Pietro Floridia (Palermo, Politeama, June 1896), and Giovanni Gallurese by Italo Montemezzi (Dal Verme, October 1905). Their last appearance together seems to have been Lohengrin at La Fenice, Venice, in January 1906.

Garbin sang frequently with Bellincioni: at the Politeama Genovese in April 1897 in Manon once more, and in Cavalleria rusticana with Bellincioni’s sister Saffo Bellincioni Frigiotti as Lola, in April 1897 at the Politeama Genovese in A Santa Lucia by Pierantonio Tasca (with sister Saffo as Maria) and Carmen; in Fedora (Lisbon 1900 and 1901), Tosca, and La bohème (Lisbon 1901), Cavalleria rusticana (Lisbon 1901), and La figlia del reggimento (presumably one of Bellincioni’s gala nights, Lisbon 1901), and Adriana Lecouvreur (San Carlo, Naples, February 1905).

Other highlights of this long and busy career include a season at Barcelona from November 1899 to April 1900. On 10 November 1900 he created the role of Milio in Zazà at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, with Storchio and Sammarco, repeating his success at the Politeama Genovese in May 1901 (with Emma Carelli as Zazà), and in Buenos Aires and Montevideo in August 1902 (with Hariclea Darclée and Titta Ruffo).

He first sang Iris with Rosina Storchio in Barcelona in 1900, and in Lisbon in 1901 (with Giuseppe De Luca as Kyoto) together with Tosca with Bellincioni and Darclée alternating in the title role. He sang in a revival of I lombardi in Florence in January 1902 with Adalgisa Gabbi. In Buenos Aires in July 1902 he sang Germania with Mario Ancona as Worms, repeating the opera in Montevideo, where Ancona was also Scarpia to Garbin’s Cavaradossi. They appeared together in Germania and Tosca in a season at the Zizinia Theatre of Alexandria in December and Cairo in January 1903. In May through August 1904 he was back in Buenos Aires and Montevideo, where he sang with Angelica Pandolfini in Adriana Lecouvreur and Tosca, Maria Farneti in Manon Lescaut and La Wally, and with Storchio in La bohème, Manon, and in her first re-trial of Madama Butterfly after the Milan fiasco. His Odessa season of January-February 1904 included Nápravnik’s Dubrowski. In April 1905 Garbin and Stehle sang Adriana Lecouvreur in Son-zogno’s season at the Théâtre Sarah Bernhardt, Paris, to which he added Zazà (with Sammarco). In his 1906 season in Buenos Aires and Montevideo Garbin sang with Krushelnytska and Riccardo Stracciari in La Gioconda (with Ninì Frascani), La Wally (with Esperanza Clasenti), Tosca and Loreley (with Clasenti). Storchio joined him again for Madama Butterfly and La traviata. In December 1906 he returned to La favorita, after some years, with Parsi-Pettinella and Sammarco. Returning to Buenos Aires yet again for the 1907 summer season he sang Mefistofele with Krushelnytska and Didur, Carmen with Maria Gay and De Luca and La favorita with Parsi-Pettinella and De Luca, and other operas including Smetana’s La sposa venduta (Prodaná neveˇsta) in which De Luca also appeared.

He repeated Lohengrin at the Teatro Adriano, Rome in October 1906, in Buenos Aires and Montevideo in July 1907 (with Krushelnytska, Parsi-Pettinella and Didur), and at the Teatro Bellini, Catania in March 1913 (with Anna Fitziù).

At the Teatro Verdi, Florence, in April 1908, he sang in Rhea by Spyros Samaras (repeated in Parma and Rome the following year); in June he made his less than triumphant appearance at Covent Garden in Tosca with Lina Cavalieri and Antonio Scotti. In October he was Don José to the Carmen of Eugenia Mantelli at the Politeama Genovese, which was one of her last appearances. In December he returned to La Scala in Andrea Chénier, followed in February by a revival of Iris.

At Buenos Aires, Rosario de Santa Fe, and Santiago de Chile in the summer of 1909 he sang mostly with Carelli and the baritone Viglione-Borghese, but with Virginia Guerrini, Nunzio Rapisardi, and Nazzareno De Angelis in La favorita. 1909 also brought first performances of Montemezzi’s Hellera at the Regio, Turin in March, followed at the same theater in December with his first Tristan, with Elsa Bland as Isolde; Fiorello Giraud sang the sailor. In February 1910 Elsa Bland rejoined him for La festa del grano by Don Giocondo Fino at the Regio, followed by further performances of the opera at the Costanzi, Rome. After performances in Valparaiso and Budapest, Garbin returned to Florence in October 1910 for Loreley with Eugenia Burzio. In April 1911 he sang Mugnone’s Vita bretone at the Massimo, Palermo and in November 1912 La Dubarry by Ettore Camussi at the Lirico, Milan.

His only appearances in Saint Petersburg were in January-February 1912: Rigoletto with Olimpia Boronat, Battistini, and Arimondi; Manon with Cavalieri and Arimondi; Tosca with Cavalieri and Battistini. Later in the year he returned to Barcelona. He had another chance to sing I lombardi at the Comunale, Bologna in 1913, with Ester Mazzoleni. Vocal generations overlapped when, in January 1913, he sang Rigoletto at the Costanzi with Amelita Galli-Curci. At the Regio, Turin in February 1914, he made one of his rare appearances in Madama Butterfly, with Maria Farneti.

During the war Garbin made sporadic appearances in Florence, Rome, Padua, and Venice, including Renzo Bianchi’s Ghismonda at the Quirinale, Rome in June 1916, and at La Scala in September 1918. He sang Madama Butterfly with Storchio and Eugenio Giraldoni at the Opéra-Comique, Paris, in February 1917 and Tosca with Tina Poli-Randaccio and Sammarco in Zurich in June 1917. His last traced performance was Tosca with Bianca Scacciati at the Teatro Sociale, Lecco in September 1920. He died in Brescia on 12 April 1943.

Repertoire

Garbin’s repertoire included: Ghismonda (Bianchi), Carmen, Mefistofele, La Dubarry (Camussi), Loreley, La Wally, Adriana Lecouvreur, La figlia del reggimento, Lucia di Lammermoor, Lucrezia Borgia, La festa del grano, Cristoforo Colombo, Germania, Andrea Chénier, Fedora, Siberia, Zazà, Ero e Leandro (Mancinelli), Cavalleria rusticana, Iris, Manon (Massenet), Werther, Hellera, Vita bretone, Dubrowski (Nápravnik), La Gioconda, La bohème, Madama Butterfly, Manon Lescaut, Tosca, Rhea, La sposa venduta (Prodaná neveˇsta) (Smetana), Falstaff, La forza del destino, I lombardi, Rigoletto, La traviata, Lohengrin, and Tristano e Isotta.

The Recordings

The only Italian I have ever met who remembered hearing Garbin sing in the theater declared: “Garbin had a green voice.” Certainly, it is an unusual voice, and though Garbin had the misfortune to live in a period rich in golden-voiced tenors, he managed his resources skillfully and enjoyed a long and successful career. A well-trained voice, with a fluent and spontaneous emission, but with the peculiar feature of a very open sound in the medium register combined with a traditionally placed, properly “covered” and very brilliant and easy top. The open vowels in the medium range were cultivated by certain nineteenth-century Italian tenors, perhaps to suggest a boyish quality, corresponding to the “girlish” quality in the voice of Tetrazzini and other coloratura sopranos. We find it also in the records of Valero and Viñas. Often described as voix blanche, this open quality was adversely commented upon by New York critics during Caruso’s first season there; he was quick to correct this “fault”. The progressive darkening of Caruso’s voice set such a fashion, spread through the medium of his records, that most tenors would henceforth avoid the “open” sound. To Anglo-Saxon opera lovers the “open” vowels, especially when combined with a vibrato as evident as Garbin’s, suggested an unmanly bleating. Garbin’s vibrato, although it displeased London audiences in 1908, does not seem excessive on records and must have added brilliance and impact to the voice in the theater. His distinctive style is a mixture of the caressing, lovingly lingering manner of the previous generation (De Lucia) with the forthright, impetuous, and even barn-storming phrasing of the new verismo school. His records may, at first, be slightly disconcerting, for Garbin’s approach to his music is not regulated by any very sound or refined musical taste, but his interpretations are both impassioned and sensitive. His enunciation is well forward on the lips and his pronunciation of Italian, despite the “open” vowels, is a delight.

Garbin has his importance as a first-generation interpreter both of Verdi and Puccini. Unfortunately he never recorded Fenton’s song from Falstaff, of which in 1913 the Corriere della Sera said: “It seems that time stands still for this tenor, who, last night, after twenty years, sang the third act sonetto with all the sweetness with which he sang it on the night of the opera’s first performance.” His prowess as a Verdi singer is revealed in his lovely performance of the duet “Solenne in quest’ora” from La forza del destino, the opera of his debut, with a colleague with whom he sang frequently, the baritone Mario Sammarco. Both voices are well recorded and Sammarco is at his best, his rich baritone well focused. Garbin phrases “Or muoio tranquillo” beautifully, though, like Caruso in his matchless recording, he breathes after “Vi stringo” in order to have enough breath for the loving fermata he effects on the high A of “al cor mio”. (The elderly Marconi manages this long phrase in one breath.) The two colleagues also collaborate in an elegant version of the duet from Act IV of La bohème, with expressive rubato and some charming coloring from Garbin. Although Garbin never sang Aida, both he and Oreste Luppi declaim with appropriate breadth and grandeur the temple scene, “Nume custode e vindice”, in which, curiously, Garbin repeats the words of the opening bass solo instead of what is set down for Radamès in the libretto.

Like De Lucia and Zenatello, Garbin thought fit to enrich the G&T catalogue with a record of the duet “Un dì felice, eterea” from La traviata sung as a solo, and like them he graces the “big tune” at “dell’universo” with the same lovely ornament that we hear in their records, too, as well as in the records of “Ah, fors’è lui” by many sopranos.

The G&Ts bring us two selections each from Manon Lescaut and La bohème, operas which he was among the first to sing, and which he kept in his repertoire for years. Within their limitations, they do, indeed, teach us something about the manners of early Puccini singers. On two G&Ts and a Fonotipia (discounting a later Columbia) we have three similar, but not identical interpretations of “Donna non vidi mai”, an aria that might have been written for Garbin, so skillfully does he realize Puccini’s alternating between loud (con anima) and soft singing (dolcissimo). The ten-inch G&T reproduces most thrillingly the brilliant high B-flats, whereas the Fonotipia is perhaps a more polished performance. His gentle attack on the first phrase—“I have never seen a woman anything like this one”—(marked con accento appassionato though also piano) perfectly suggests a delighted inner communing, and he produces a lovely soft head note at “l’alma mia si desta”, and again at “parole profumate”. He underlines his points with unwritten, though convincing rallentando. There is a smile always present, and a youthful ardor. At the first appearance of the phrase “O sussurro gentil” Garbin makes the same musical mistake in all three versions. A deliberate change is made in the last phrase, “deh! Non cessar!”, where he executes the triplet on the second syllable instead of the first, as written. “Guardate, pazzo son” is an interesting contrast. Here Garbin manages to express the passionate hysteria of De Grieux without ever distorting the musical line; he wrings out the last drop of anguish without resorting to sobbing. From the first notes of the recitative, “Ah! Non v’avvicinate!”, the voice is carefully placed in the mask with the correct “covered” tone, with thrilling sound on the high G and A. When he comes down into the medium range, Garbin does not here indulge in his usual “open” vowels, and this seems to be typical of his method when the musical phrase begins high and drops gradually into the medium. His technique is more sophisticated than it might at first seem, and he is able to control the sounds he wants to make. After these two splendid performances, the abbreviated “Che gelida manina” is rather disappointing: Garbin ignores the many piano markings, changes several notes, and lacks charm; at least he does supply a grand portamento di voce on the many occasions in which Puccini demands it. He manages better in his vivid enunciation of the dramatic monologue “Mimì è una civetta” from Act III, but even here he could have used more dynamic contrast as the score does call for it.

Despite all his vivacity and charm, one begins to notice that Garbin’s singing essentially lacks just that finishing touch of loving care for the music that distinguishes the greatest artists. His attractive record of “Il sogno” (The Dream) from Manon illustrates this: his is a typically Italian performance of its day, similar in style to the versions by Anselmi, Caruso, and De Lucia, with pleasingly light head notes and a very liberal use of Massenet’s permission to hold a note as long as you like while the pianist waits. However, the other tenors mentioned are all far more polished, and however ambitious Garbin may be, his effects are not always accomplished with complete success; sustained notes at the end of phrases tend to lose support. Both the “Siciliana” and the “Brindisi” from Cavalleria rusticana are of interest because Garbin reproduces what he can manage of the then “traditional” embellishments of Stagno, the original Turiddu. With the tenor hidden behind the curtain, it must have been difficult for a conductor to keep singer and harp together with such liberal rubato and so many pauses; the vocal line is graced with many a mordent. Garbin sings this appealingly, and his attempt at the Stagno variants (minus the long trill) in the “Brindisi” is praiseworthy. (These ornaments will be familiar to those who know the Caruso record.) Garbin avoids Caruso’s falsetto high C but, like Schipa, enjoys emitting a resounding B-natural on the last chord.

The Quartet from La bohème and the duet from Adriana Lecouvreur give us our sole opportunity to hear the voice and art of Adelina Stehle, for these are her only published recordings. She seems to possess a good, strong voice, very pleasant except when she forces her chest register up to A-flat, and though her style is that of a polished verismo singer, she is able to float a beautiful soft A-flat above the stave at “Niuno è solo l’april”, suggesting a fine basic training. This is an effective performance of the Quartet, in which a great deal of expressive rallentando is introduced—like many others, Stehle slows down considerably for “Soli!” on the low E-flat—D-flat, though Puccini has instructed Mimì to accelerate slightly here. Camporelli is an excellent Musetta (a role she sang at La Scala), humorous without heaviness, and Sammarco is at his best as Marcello. Garbin phrases well, but here again one wishes he would introduce more shading. Shading is not required in the duet “Ma, dunque è vero” from Adriana Lecouvreur, where husband and wife, having already sung their roles in the theater, go at it hell-for-leather. Like Caruso, Garbin recorded part of the opera’s final duet, “No, più nobile sei delle regine” without bothering to engage a soprano for Adriana’s part—I wonder what Stehle thought about this! Although Garbin is not as accurate as Caruso in the execution of the gruppetti, this is a meltingly lovely performance in which he manages to observe all the contrasting dynamic requirements of the score.

Leoncavallo spent part of his youth as a cafe pianist, and in Act One of Zazà (as in Act Two of Pagliacci) he was able to make use of this experience, writing some delightful “vaudeville” music. It is sadly typical that when, in 1947, the Sonzogno publishing house printed a new edition of Zazà, the editor cut out Milio’s arietta “È un riso gentil” together with the bubbling duet for Zazà and Cascart, “Il bacio”, that follows it. Garbin’s performance of the arietta makes a charming souvenir of the last important role he was to create—he is so winning that we are not surprised to learn that, on the first night of the opera, he was called upon to encore it.

Fiorello Giraud

Life and Career

Giraud was born in Parma on 22 October 1870, son of another parmense tenor, Lodovico Giraud, born on the second of March 1846, and who made his debut at the Teatro Dal Verme, Milan, in 1872 in Petrella’s Jone. In 1879 Lodovico Giraud sang with Battistini in Persiani’s L’assedio di Cesarea at the Teatro Marrucino, Chieti. He died of yellow fever in Guadalajara in 1882.

Fiorello studied with the tenor Ernesto Barbacini at the Conservatorio in Parma, and made his debut at the Teatro Civico, Vercelli, in Lohengrin in December 1891. Although the word was being passed around that Giraud was effeminate on stage, Leoncavallo went specially to hear him sing, liked him—“that poor boy”—and engaged him to create the role of Canio in Pagliacci at the Teatro Dal Verme, Milan, on 21 May 1892, with the all-star cast of Stehle, Maurel, Mario Ancona, and Francesco Daddi, conducted by Arturo Toscanini. The young Giraud’s interpretation became famous and was heard in 1892-1893 in Ancona, Parma, Alessandria, Brescia, Modena, Verona, Ballarat, and Melbourne. (In February and April 1893, at Modena and Verona, he may have been the first tenor to sing both Cav and Pag on the same evening.) He continued to sing Canio in 1894 at Pavia’s Teatro Manzoni, Milan and Warsaw; in 1895 at Milan’s Teatro Lirico and Rome’s Teatro Nazionale; in 1898 at the Municipal, Santiago de Chile; in February 1899 (and eleven years later in March 1910) at Lisbon’s São Carlos; and in 1903 in Buenos Aires and Rosario de Santa Fe. In the 1890s his repertoire included Falstaff (conducted by Toscanini at the Teatro Comunale, Bologna, and the Teatro Carlo Felice, Genoa in November and December 1894), L’amico Fritz (Melbourne 1893), Cristoforo Colombo, Carmen, Isidore De Lara’s Amy Robsart at the Pagliano, Florence in March 1896, Leoncavallo’s Chatterton at the Teatro Brunetti, Bologna in June 1896, and Puccini’s La bohème (Teatro Filarmonico, Verona, 1897). At the Teatro Nazionale, Rome, on 29 February 1896, he sang in a performance of Rossini’s Petite messe solennelle, conducted by Mascagni, which was repeated in Pesaro.

In May 1895 he sang with Luisa Tetrazzini and Pietro Cesari in Rosario de Santa Fe. From December 1896 to January 1897 he was at the Teatro Liceu, Barcelona, where he sang La Gioconda and Manon Lescaut with Eva Tetrazzini and Elisa Petri alternating as the heroine, and his first Tannhäuser, and spent a season from June 1898 touring South America, Portugal, and Spain with Eva Tetrazzini. In December 1901 he sang in Cairo and Alexandria with Angelica Pandolfini and Titta Ruffo in Fedora, La bohème, Tosca, and Iris. At Madrid in 1899-1900 he sang in La bohème, Tosca, Lohengrin, Carmen, and in 1908-1909 in La Walkiria, Sigfrido, and Tosca. In January 1899 he sang Massenet’s Sapho at the São Carlos, Lisbon, returning there in 1902, 1903, and finally in March 1910 to sing Tristano e Isotta and Lohengrin. His first Tristan was also the opera’s first performance in Rome, at the Teatro Costanzi on 26 December 1903 with Amelia Pinto and Antonio Magini-Coletti, conducted by Luigi Mancinelli, followed by Tosca with Hariclea Darclée, Lohengrin, and Mancinelli’s Ero e Leandro. Then came other Wagnerian roles: La Walkiria and Sigfrido (Teatro Verdi, Trieste, April 1906) and Il crepuscolo degli dei (La Scala, 1907-1908). At La Scala he also took part in Toscanini’s successful presentations of Charpentier’s Louise and Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande (1908). At La Fenice, he appeared in Falstaff and Le Villi (1895), I maestri cantori di Norimberga, Il trillo del diavolo (Stanislao Falchi), and Iris (1899-1900), and one performance only of Lohengrin in 1911.

Other world premieres for Giraud included Vendetta by Arturo Berutti at the Carcano, Milan (October 1892), Pater by Stanislao Gastaldon at the Manzoni, Milan (April 1894), Il piccolo Haydn by Gaetano Cipollini (Warsaw, November 1894), Fadette by Dario De’ Rossi (Teatro Nazionale, Rome, 28 January 1896), Lena by T. Zignoni (Verona, April 1897), Medea by Vincenzo Tommasini (Teatro Verdi, Trieste, 8 April 1906), and Sperduti nel buio by Stefano Donaudy (Teatro Massimo, Palermo, 27 April 1907).

After 1910 his public appearances seem to have been confined to concert work. He died in Parma on 28 March 1928.

Repertoire

Giraud’s repertoire included: La dannazione di Faust, Carmen, La Wally, Louise, Pelléas et Mélisande, Amy Robsart, Il trillo del diavolo, Cristoforo Colombo, Germania, Andrea Chénier, Fedora, Siberia, Faust, Chatterton, Pagliacci, Zazà, Ero e Leandro, L’amico Fritz, Cavalleria rusticana, Iris, Lorenza, Sapho (Massenet), La Gioconda, La bohème, Madama Butterfly, Manon Lescaut, Tosca, Le villi, Ernani, Falstaff, La traviata, Il crepuscolo degli dei, Lohengrin, I maestri cantori di Norimberga, Sigfrido, Tannhäuser, and Tristano e Isotta.

The Recordings