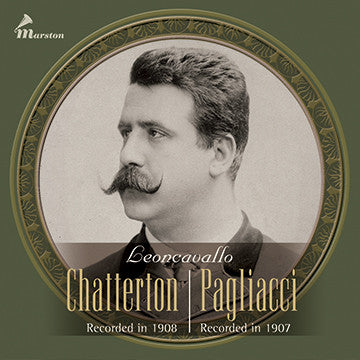

Ruggiero Leoncavallo (1858-1919)

ChattertonRecorded in Milan, May 1908Opera in three acts Recorded in twenty-six parts Words and music by Ruggiero Leoncavallo Set in the vicinity of London, ca.1770 (First performed at the Teatro Drammatico Nazionale, Rome, 10 March 1896) | |

| Thomas Chatterton | Francisco Granados |

| Thomas Chatterton | Francesco Signorini |

| John Clark, a wealthy proprietor | Francesco Frederici |

| Jenny Clark, his wife, a Puritan | Ines de Frate |

| Young Henry, her brother | Annita Santoro |

| Giorgio, an elderly Quaker, Jenny’s uncle | Giuseppe Quinzi-Tapergi |

| Lord Klifford | Francesco Cigada |

| Skirner, a moneylender | Gaetano Pini-Corsi

|

|

Ruggiero Leoncavallo, conductor Chorus and orchestra: Teatro alla Scala Producer: Stephen R. Clarke Audio Conservation: Ward Marston Photographs: Roger Gross Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi Marston would like to thank Richard Bebb, Leonard D. Court, Ruth Edge, Lawrence F. Holdridge, Iain Miller, Alan McCormack, and Lloyd Stickles for their help in the production of Chatterton. Marston would also like to give special thanks to Richard Bebb, Lawrence F. Holdridge, and the late Sir Paul Getty for their generosity in sharing exceedingly rare recordings. | |

| |

Ruggiero Leoncavallo (1858-1919)

PagliacciRecorded in Milan, June 1907Opera in two acts Recorded in twenty-one parts Words and music by Ruggiero Leoncavallo | |

| Canio (Pagliaccio) | Antonio Paoli |

| Nedda (Colombina) | Giuseppina Huguet |

| Tonio (Taddeo) | Francesco Cigada |

| Silvio (Villager) | Ernesto Badini |

| Beppe (Arlecchino) | Gaetano Pini-Corsi |

| A peasant | Giuseppe Rosci

|

|

Ruggiero Leoncavallo, conductor Chorus and orchestra: Teatro alla Scala Producer: Stephen R. Clarke Audio Conservation: Ward Marston Photographs: EMI Archive and Roger Gross Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi Marston would like to thank Roger Beardsley, Ruth Edge, J. Neil Forster, Lawrence F. Holdridge, Johnson Victrola Museum, Delaware State Museums, Dover, Delaware, Leigh Martinet, and Mark Obert-Thorn for their help in the production of Pagliacci. | |

Chatterton | ||

| CD 1 (79:04) (FS) Francesco Signorini, (FG) Francisco Granados | ||

| ACT I (31:33) | ||

| 1. | Charley! Holger! Chatterton (FG); Giorgio; John | 2:09 |

| 1462c (54233) | ||

| 2. | Lord Klifford qui desidera John; Jenny; Giorgio | 2:06 |

| 11205b (54389) | ||

| 3. | Uh! L’orso si allontana! Henry; Chatterton (FG); Giorgio | 2:48 |

| 11202b (54388) | ||

| 4. | Che hai? Scrissi una lettera Giorgio; Chatterton (FS) | 3:02 |

| 11199b (54386) | ||

| 5. | Vedeste Mistress Clark? Chatterton (FG); Giorgio; John; Lord Klifford | 3:21 |

| 11201b (54390) | ||

| 6. | Signori, vi presento Jenny; Chatterton (FG); John; Lord Klifford | 3:30 |

| 1465c (054234) | ||

| 7. | Dacchè sei giunto Chatterton (FG); John; Giorgio; Lord Klifford | 4:13 |

| 1461c (054235) | ||

| 8. | John, dite che ci apprestino Chatterton (FG); Jenny; John; Lord Klifford | 3:22 |

| 11203b (54391) | ||

| 9. | Gli amici suoi perchè Jenny; Chatterton (FG); Giorgio | 3:17 |

| 1470c (054236) | ||

| 10. | Ne’ pieghi del sudario Jenny; Chatterton (FS) | 3:45 |

| 11200b (54374) | ||

| ACT II (36:33) | ||

| 11. | Preludio orchestra | 2:54 |

| 11295b (50579) The month of this recording is not documented. | ||

| 12. | Intermezzo: A Dio sia gloria chorus | 3:49 |

| 1474c (054515) | ||

| 13. | Stanco spossato arresta il triste pellegrin Chatterton (FS) | 3:45 |

| 1469c (052253) | ||

| 14. | Tu sola a me rimani Chatterton (FS) | 2:31 |

| 11210b (2-52668) | ||

| 15. | Son certo ch’ei dorme Henry; Chatterton (FG) | 3:04 |

| 11211b (54392) | ||

| 16. | Là... là.... presso a quel tavolo Henry; Chatterton (FG) | 3:19 |

| 11209b (54393) | ||

| 17. | Che hai? Tom di’, che hai? Henry; Jenny; Giorgio | 3:37 |

| 1468c (054237) | ||

| 18. | Un angiol sei! Ma datti pace Jenny; Giorgio | 3:48 |

| 1471c (054238) | ||

| 19. | Skirner! qui!... Voi stesso! Chatterton (FG); Skirner | 3:12 |

| 1463c (054239) | ||

| 20. | È finita, mio Dio! Chatterton (FG); Giorgio | 3:16 |

| 11212b (54394) | ||

| 21. | Che parli mai! Che vuoi tu dire! Chatterton (FG); Giorgio | 3:18 |

| 11215b (54395) | ||

| ACT III (18:12) | ||

| 22. | Ah! Mistress! Chatterton (FG); Lord Klifford | 3:14 |

| 11214b (54396) | ||

| 23. | Di lacrime Chatterton (FS) | 4:24 |

| 1472c (052255) | ||

| 24. | E un pane chi chiedeva a costui? Chatterton (FS) | 3:20 |

| 1473c (052254) | ||

| ||

| CD 2 (78:14)

| ||

| Chatterton (continued) ACT III (continued) | ||

| 1. | Sui vanni suoi la morte Jenny; Chatterton (FS) | 3:44 |

| 1466 1/2c (054232) | ||

| 2. | …e perché mai? Ah! Patria infame Jenny; Chatterton (FS) | 3:43 |

| 1467c (054231) | ||

Pagliacci | ||

| 3. | Prologo, Part I: Si può? Tonio | 4:05 |

| 1209 1/2c (052163) | ||

| 4. | Prologo, Part II: Un nido di memorie Tonio | 3:07 |

| 1208c (052162) | ||

| ACT I (14:39) | ||

| 5. | Son qua! chorus | 2:32 |

| 10601b (54673) | ||

| 6. | Mi accordan di parlar…Un grande spettacolo! Canio; chorus; Tonio; Beppe; A peasant | 2:54 |

| 1215 1/2c (054156) | ||

| 7. | Un tal gioco Canio; chorus | 3:58 |

| 1216c (052168) | ||

| 8. | Ah! Andiam! (Coro della campane) chorus | 3:02 |

| 1212c (054507) | ||

| 9. | Qual fiamma avea nel guardo... Stridono lassù Nedda | 4:23 |

| 1225c (053130) | ||

| 10. | Sei là? Credea che te ne fossi andato... So ben che difforme Nedda; Tonio | 3:58 |

| 1221c (054150) | ||

| 11. | Bada! Oh, tosto sara i mia…Decidi il mio destin Nedda; Tonio; Silvio | 3:44 |

| 1218c (054147) | ||

| 12. | Nedda, Nedda, rispondimi…E allor perchè Nedda; Silvio | 3:23 |

| 1219c (054148) | ||

| 13. | Nulla scordai…Cammina adagio Nedda; Silvio; Tonio | 3:04 |

| 1220c (054149) | ||

| 14. | Aitalo…Signor Canio; Nedda; Tonio; Beppe | 4:02 |

| 1230 1/2c (054157) | ||

| 15. | Recitar!…Vesti la giubba Canio | 6:50 |

| 1210c (052166) | ||

| 16. | Intermezzo | 3:54 |

| 10596b (50544) | ||

| ACT II (17:51) | ||

| 17. | Ohè! Ohè! Presto! chorus; Tonio; Beppe; Silvio; Nedda | 3:15 |

| 1213 1/2c (054146) | ||

| 18. | La commedia: Pagliaccio, mio marito…Ah! Columbina Nedda (Colombina); Beppe (Arlecchino) | 3:53 |

| 1222 1/2c (054151) | ||

| 19. | La commedia: Di fare il degno convenuto Nedda (Colombina); Tonio (Taddeo); Beppe (Arlecchino) | 1:59 |

| 1229c (054152) | ||

| 20. | La commedia: Arlecchino!…Colombina! Nedda (Colombina); Beppe (Arlecchino); Tonio (Taddeo) | 2:38 |

| 10605b (54338) | ||

| 21. | La commedia: Versa il filtro, nella tazza sua! Beppe (Arlecchino); Nedda (Colombina) | 2:58 |

| Nome di Dio! Canio; Nedda; Tonio | ||

| 10609b (54339) | ||

| 22. | No, Pagliaccio non son! Canio; chorus; Silvio | 3:08 |

| 1211 1/2c (052167) | ||

| 23. | Finale: Ebben se mi giudichi di te indegna Nedda; Canio; Beppe; Tonio; Silvio; chorus | |

| 1231c (054158) | ||

The Leoncavallo Recordings

1907/1908

Chatterton

The known facts of the life of Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770) are very sketchy. He was born in Bristol where he received a good education at a local school. His family was poor and he fabricated some poems for sale, claiming they were manuscripts of the work of one Thomas Rowley, a monk and poet resident in Bristol. Rowley is now accepted to be fictitious. Chatterton used some of these faked manuscripts in an attempt to obtain financial assistance from Horace Walpole, who was temporarily taken in but eventually declined to assist Chatterton. He made a few sales and decided to come to London in 1770 to attempt his fortune. He successfully produced a burlesque opera, The Revenge, but soon ran out of money and supporters and he took his own life with arsenic on 24 August 1770. The poems that survive, his own and the faked archaic poems, are universally conceded to be the work of a poetical genius.

For six or seven decades after his death a scholarly debate ensued about the authenticity of the early poems and the existence of Rowley, but it is generally conceded that all the surviving poems are the original work of Chatterton himself. His story became the subject of much interest. It is a stretch to suggest that he was the real life prototype for Werther but the romantic writers were much taken with the story of his life and with his writing. Coleridge wrote a ‘Monody on the Death of Chatterton’ in 1796. Blake believed that the archaic poems were genuinely the work of Rowley. Keats wrote an ode to Chatterton in 1815 and in ‘Resolution and Independence’ Wordsworth refers to Chatterton as ‘…the marvelous boy…who perished in his pride.’

Interest in the story was waning in England when it traveled to France, where it became the vehicle for a successful play by Alfred de Vigny, which premiered in 1835. In the play, the story was embellished to include a love interest between Chatterton and his landlady Kitty, who was played by the popular actress, Marie Dorval. She created a very melodramatic fall to her death down a staircase after she discovered Chatterton’s corpse. (In Leoncavallo’s opera Kitty is renamed Jenny.) The play was a great hit and was revived regularly in Paris over the next thirty years. The play also was a foreshadowing of modern theater and modern opera in that there was little action, just the psychological tension of the central figure contemplating suicide throughout. Balzac saw the play and summarized it: ‘First Act: shall I kill myself? Second Act: I should kill myself. Third Act: I do kill myself.’

The play was translated into German and Italian and caught the fancy of the young Leoncavallo, then eighteen, who was trying to be both a successful poet and a successful musician. He had just graduated from the Naples Conservatory. He wrote the opera Chatterton in 1876, originally in four acts, and even succeeded in arranging for it to be produced. He put up some funds himself but the promoter of the planned performance absconded, leaving Leoncavallo with serious debt. He spent the next fifteen years of his life taking any work he could procure in cafés, giving voice lessons, teaching piano, and accompanying, including even a brief spell as a piano recitalist in Cairo. His years of travail finally ended in 1892 with the success of Pagliacci, a short potboiler written when he was at the very bottom of his fortunes. With its success it was possible for him to have Chatterton produced in 1896, now reworked for publication into three acts. Although Chatterton never achieved the success of Pagliacci, and nothing he wrote ever repeated that success, Chatterton was not completely unsuccessful. Massenet wrote to Leoncavallo in 1896 to congratulate him after he had read that the tenth performance had been an enormous public success. Chatterton was revived several times in Leoncavallo’s lifetime, most often in France, where it has been occasionally revived since and where de Vigny’s play is still occasionally performed. Leoncavallo talked of reworking the opera for a baritone lead and Tita Ruffo even recorded the aria ‘Tu solo a me rimani’ in November, 1908. In October, 1909, Leoncavallo wrote to Ruffo to say that he had sent the transcribed score of Chatterton to Sonzogno, his publisher, so it appears that he did complete it, but it doesn’t seem to have been performed.

Pagliacci

While it seemed important to add Pagliacci to this re-issue of Chatterton, it didn’t seem necessary to write detailed notes about Pagliacci or to include a libretto. It is worth noting, however, that this recording of Pagliacci is virtually complete except for a note or two here and there.

The Recordings

HMV’s recordings of Leoncavallo’s operas Pagliacci and Chatterton made in 1907 and 1908 are of seminal importance in the history of recording, not only for the participation of the composer but also as the beginning of a century-long commitment to the recording of complete works. The Pagliacci recording was an enormous success for HMV and the first great success of a many-sided recording of a vocal work. Some of the sides were available separately and are consequently fairly common. Others are far more elusive. The Chatterton recording was not a success and all of the sides are among the rarest of 78s. So far as can be determined, no single archive or collection contains a complete set of the 28 sides that were recorded. Richard Bebb and the late Sir Paul Getty, who amazingly owned all of the sides between them, were very generous to allow all of them to be transferred digitally for the purposes of this CD reissue. Lawrence Holdridge also supplied excellent copies of several of the Francesco Signorini sides.

Not much documentation survives about the recordings, but there are a few pertinent items in the EMI Archive at Hayes. A wire dated 3 April 1907 reads that Leoncavallo is prepared to direct Pagliacci for a fee of £200 and a decision is needed. The reply accepts Leoncavallo’s terms and adds that the contract must provide for repetition ‘until perfect of all records’. The contract either wasn’t signed or is lost. A letter of 1 August 1907 shows that Leoncavallo had still not signed the contract but that the records were made in any event and that they have ‘come out very good.’

HMV was evidently confident enough in the result that a contract dated 23 September 1907 was entered into, which does survive. HMV acquired the recording rights to Leoncavallo’s Chatterton, Maia, Camicia Rossa, and the rights to any other opera he might write in the future for 1,000 francs for each act of each opera plus 25 centimes royalty for every record sold. Leoncavallo undertakes to ‘conduct personally on the request of the company the performances that will be necessary for the perfect recording of his operas.’ It was planned to record Chatterton in the autumn of 1907 but for reasons that are unclear in the correspondence the recordings did not take place until 1908. A budget also survives, which was submitted to London by the Milan office for recordings to be made in 1908 with 3,000 francs duly budgeted for Leoncavallo based on Chatterton being three acts long.

No publicity literature survives for Chatterton and it is not known just how and where it was ever released. The sides sung by Francesco Signorini were released as red label recordings and, though rare, do show up. The rest of the opera was issued with black labels and they have almost never surfaced. To our knowledge only one complete set of the black label series is extant. Publicity literature does survive for Pagliacci. The set sold in the U.K. for £6.00 and the front page of the brochure states: ‘Each one of these Records was made in the presence of and under the Conductorship of the Composer, Sig. R. Leoncavallo.’ Later in the brochure there are two further things worth noting. It states that Signor Caruso has also sung Canio’s ‘songs’ and says that ‘the advantage of Leoncavallo’s presence as musical director is one that should make this issue ever valuable and unique.’ A photograph was taken of the entire cast and both Leoncavallo and Carlo Sabaino are in the photograph, each described as ‘Maestro.’ Finally, there is a letter in the file at the EMI Archive dated 6 September 1907 from the English Branch of The Victor Talking Machine Company asking HMV to send to them, at the earliest possible moment, a complete set of the shells for Pagliacci, excluding the tenor aria ‘Vesti la giubba.’ In fact, The Victor Company offered the Pagliacci set with ‘Vesti la giuba’ sung by Enrico Caruso rather than Antonio Paoli, which accounts for Victor not requesting the Paoli master.

This review of the surviving material related to these recordings raises two big questions that have never really been answered. First, in spite of the labeling of the Pagliacci records themselves, who was actually conducting this recording and second, why in the course of the Chatterton recording are two different tenors, Francesco Signorini and Francisco Granados, singing the part of Chatterton?

Until Fred Gaisberg published his memoirs, it was always assumed that the Pagliacci recording was conducted by Leoncavallo. Gaisberg said that, although Leoncavallo was present, Carlo Sabaino conducted, which permitted HMV to say that the recordings were conducted by the composer, which is how the labels actually read. Gaisberg, in his memoirs, was often free with the facts if it improved his story line. It will never be possible to say for sure who conducted each side. It is surprising that in the Leoncavallo files at Hayes there is nothing in internal correspondence that corroborates Gaisberg’s story. In fact, Sabaino is not mentioned at all in any of the internal correspondence. It is also surprising that the contract documents that postdate the Pagliacci recording make it clear that Leoncavallo is to conduct Chatterton personally. That seems an unusual turn of phrase if at that point HMV was in fact only seeking his imprimatur. You would think that, if the Gaisberg story were completely accurate, the contract would require his presence at the recordings and not that he conduct. In the recording budget that survives for 1908, there is no budgeted fee for Sabaino, but there may not have been since Sabaino was on staff at HMV. Gaisberg does not mention the Chatterton recordings at all. One could understand how HMV might have been happy to fool their buyers in order to increase sales, but why would their internal documents be written as though they were also trying to fool themselves?

Concerning the second question, one possible explanation about the fact that there are two tenors singing Chatterton’s music is that HMV didn’t have the idea that they were recording a single unbroken performance but only that they were making all of the music in the opera available. Another possibility is that Signorini had not learned the complete role and HMV was pressed for time. We deduce that both tenors were at the same recording session since matrix 1468c is a Granados side, 1469c is a Signorini side, and 1470c is a Granados side. They each recorded the aria ‘Tu sola a me rimani.’ Granados’s recording of it is matrix number 11216b, which was issued as 2-52688 and appears erroneously in Alan Kelly’s His Master’s Voice/La Voce del Padrone with the title ‘Son certo.’ Space exigencies have caused us to spare the listener his performance and we can only lament here that Signorini did not record all of Chatterton’s music.

Chatterton, as published, is in three acts. In this recording, each act was somewhat abridged, with Act 3 being the most heavily cut. Fortunately, these excisions do not alter the story line. The aria for Lord Klifford sung by Cigada (CD 1, Track 6) has a second verse that does not appear in the published score and despite the patient efforts of several Italian-speaking listeners, it was not possible to decipher the words completely. Finally, a careful examination of the harmonies of the recorded music leading to ‘Tu sola a me rimani’ and the final track of Act 3 reveal changes from the published score that cause the music that follows to be a semitone lower than the published score. Whether the changes were to accommodate Signorini or were yet another re-working of the score by Leoncavallo, we cannot tell.

All that was recorded is set out on 26 tracks, although 28 sides were recorded. The first seven pages of the score were recorded twice and this section was released as two ten-inch sides and alternatively as one twelve-inch side. Comparing these two versions, we found that the orchestra was too remotely recorded on the first ten-inch side. In addition, there are some vocal problems toward the end of the twelve-inch version. Therefore, for this re-issue, we have chosen to include the first half of the twelve-inch version followed by the second ten-inch side. (CD 1, Track 1.)

The Singers

Ernesto BADINI

(Silvio in Pagliacci) Baritone 1876-1937 • sang mainly in Italy and South America and specialized, particularly later in his career, in buffo roles. He made many recordings and appeared in several complete operas other than Pagliacci including La Boheme, The Barber of Seville, and an electric recording of Don Pasquale. He was the first Gianni Schicchi at both La Scala and Covent Garden.

Francesco CIGADA

(Tonio in Pagliacci and Lord Klifford in Chatterton) Baritone 1878-1966 • sang a very wide range of leading baritone roles from Wagner to Montemezzi, Puccini, and Rossini. He never appeared in the USA and recorded only for HMV in Milan (1905-1908). He gave up his career in 1924 after the death of his only child and retired to his hometown of Bergamo.

Francesco FEDERICI

(Giorgio in Chatterton) Baritone 1873-1934 • beginning in provincial Italian houses his career grew steadily. He appeared throughout Italy, in Helsinki, Havana, Mexico City, and for four seasons, 1913-1916, in Chicago. He collapsed while singing Fra Melitone in La Forza del Destino in Amsterdam and died there a few days later. He recorded only for HMV in Milan (1908-1912).

Ines DE FRATE

(Jenny Clark in Chatterton) Soprano 1854-1924 • the first record of her appearing in opera is of Violetta in Piacenza in 1892. She appeared as Norma at La Scala in 1898-1899 under Toscanini. Her recordings were all made for HMV in Milan including several duets with Signorini and arias from Aida, Nabucco, Lucrezia Borgia, and Norma. There is a letter in the archives of EMI written in 1908 recommending both Signorini and de Frate to the head office of the company in England, which states that ‘Signorini has a magnificent dramatic tenor voice and sings with good school and Madame De Frate although she has had 20 years career is still a fine dramatic soprano with fine old classic school so rarely to be found among young artistes of to-day.’

Francisco GRANADOS

(Thomas Chatterton in Chatterton on the sides where the part is not sung by Signorini) Tenor 1870-1946 • sang leading tenor roles in Spain (where he was born), Russia, and Italy between 1898 and 1908 and after that specialized in Zarsuela parts in Spain. His only recordings are those of Chatterton and a Pathé of ‘O Paradiso’, all recorded in 1908 in Milan.

Giuseppina HUGUET

(Nedda in Pagliacci) Soprano 1871-1951 • born in Barcelona and made her debut there in 1889. She sang in London, Paris, Milan, and Russia. She appeared at the New York Academy of Music for one season in 1898. She retired in 1912 and taught in Barcelona. She made recordings for G & T in 1903 and for HMV in 1908.

Antonio PAOLI

(Canio in Pagliacci) Tenor 1871-1946 • born in Puerto Rico, studied in Spain, and made his operatic debut in Bari in 1895. In 1902-1903 he belonged to an opera troupe assembled by Mascagni that toured the USA and Canada. He frequently toured South America and in 1920 spent a season in Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia. He eventually returned to Puerto Rico to teach. His only recordings were for HMV in Milan.

Gaetano PINI-CORSI

(Beppe in Pagliacci and Skirner in Chatterton) Tenor 1860-? • brother of the baritone, Antonio Pini-Corsi, sang for twenty seasons at the opera house in Catania and between 1892 and 1906 was regularly heard at La Scala. He sang many character parts including Mime in Siegfried and Goro in the world premiere of Madame Butterfly. He was still singing in 1932 but nothing could be discovered of his life beyond that. His recordings were for HMV in Milan.

Giuseppe QUINZI-TAPERGI

(John Clark in Chatterton) Bass 1883-? • made his debut in 1908 in Palermo and was at La Scala by 1909. He sang the King in Aida, Pimen in Boris Godounov, Boito’s Mefistofele, and Sparafucile in Rigoletto. His career was spent mainly in Italy and Argentina. He sang until 1935 in small parts. He recorded for Odeon and HMV before the First World War.

Annita SANTORO

(Young Henry, Jenny Clark’s brother, in Chatterton) Soprano 1885-? • little is known about her career except that she appeared in provincial houses in Italy and is mentioned on several recordings of ensemble scenes made by HMV in Italy before the First World War. Young Henry is of course a pants role and it is to be hoped that, in order to appear to be a young boy, she intentionally adopted the sound she makes on this recording.

Francesco SIGNORINI

(Thomas Chatterton on CD 1, Tracks 3, 9, 12, 13, and 22; CD 2, Tracks 1, 2, and 3) Tenor 1860-1927 • born in Rome and trained at the Accademia di Santa Cecilia. He made his debut in 1882 in Florence and after 1897 sang regularly in leading dramatic Italian roles at La Scala. He made guest appearances in 1907 in San Francisco and Los Angeles and also appeared in Buenos Aires. He retired in 1910 and taught in Rome. He made records for HMV and Pathé.

Stephen R. Clarke, ©2004

The two operas presented here are among the first complete operas ever recorded. Considering the limitations of the acoustical recording process, the sound of these recordings is truly spectacular. What is more, one can really feel a sense of listening to an integral performance. This is primarily due to the fact that the orchestra sounds so natural. Much of the singing is also well-recorded and the total effect is amazingly satisfying. Transferring these discs was not an easy job, however, and I feel I ought to mention some of the challenges that I encountered along the way.

The Pagliacci was originally issued on twenty-one single-sided discs, comprising seventeen twelve-inch and four ten-inch sides. It was apparently issued as a set in its own album with a brochure, although I have never known one to have surfaced. Since the complete edition would have been quite costly, buyers would have been able to purchase each disc separately. That is why the Prologue, for example, is quite common, whereas other discs such as the orchestral intermezzo are almost never seen. Later on, some of the sides from this recording were offered as double-faced discs but as far as I am aware, the solo discs by Antonio Paoli were only issued single-faced. When this recording was issued in America by the Victor Talking Machine Company, six sides were omitted: nine, ten, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, and eighteen. Since the Victor pressings tend to be quieter than their HMV counterparts, I have used mint condition Victors whenever possible. The sides that were only issued by HMV are quite scarce but fortunately, I was able to locate excellent copies of these discs. The sound on this set is extremely well balanced with the voices perfectly focused. The major flaw in the recording is the severe pitch instability that afflicts many of the sides. In order to keep the pitch constant, it was necessary to decrease the speed by several RPM during the transfer of each side. There were also some sudden lurches in pitch that I have tried to correct.

The Chatterton recording, made a year later, posed different problems than Pagliacci. The sound of the orchestra is possibly the best I have ever heard on an acoustic recording, although the playing itself is terrifically unrehearsed. The orchestration sounds quite realistic except for some harp passages that are obviously played on an upright piano placed far from the recording horn. When I began to remaster these discs, I was immediately relieved to hear that the pitch throughout the recording was quite constant. I was, however, dismayed to find that the overall sound level was considerably lower than in the Pagliacci recording which makes the background noise more prominent. By carefully choosing the proper stylus to play each side and with subtle changes in equalization, I have been able to reduce the noise to some extent. I have not employed any invasive computer-based noise reduction software which can adversely affect the sound of the recording. The singers are all clearly recorded with the exception of the tenor Francisco Granados who is, on most sides, placed so far from the recording horn as to make him almost inaudible. Perhaps this was a conscious decision either by the composer or the recording engineer since he is obviously the weakest member of the cast. In this instance, I decided not to tamper with the original sound and have therefore left Granados in the background. The only other serious problem with the recording can be heard on matrix 1473c (CD 1, Track 24.) Toward the close of the side, the sound deteriorates drastically, most likely due to a malfunction of the recording apparatus. I have only ever seen two copies of this disc and both contain the same sonic flaw.

Since no publicity documentation exists for the Chatterton recording, it seems doubtful that it was ever offered as a complete set. Given the extreme rarity of the Chatterton discs, we can assume that only a small number of each disc was pressed and even fewer were ever sold. Fortunately, at least one copy of each disc still exists so that we can hear the opera in its entirety conducted by none other than its composer. Concerning the question of whether Leoncavallo actually conducted the Pagliacci recording or merely supervised the sessions, we will probably never know the answer. In either case, this recording, replete with marvelous singing by the entire cast must be clearly viewed as the authentic version of Leoncavallo’s most popular opera.

ChattertonLyric Drama in Three Acts Words and Music by Ruggero Leoncavallo Dramatis personae | |

| Thomas Chatterton | tenor |

| John Clark, a wealthy proprietor | bass |

| Jenny Clark, his wife, a Puritan | soprano |

| Young Henry, her brother | soprano |

| George, an elderly Quaker, Jenny’s uncle | baritone |

| Lord Klifford | baritone |

| Lord Strafford | bass |

| Lord Lingston | tenor |

| Skirner, a moneylender | tenor |

| Six or seven young lords, friends of Klifford | |

| Labourers in the workhouse of John Clark | |

|

Set in the vicinity of London in the period of 1770. First performed at the Teatro Drammatico Nazionale, Rome, 10 March 1896. | |

| ATTO PRIMO La scena rappresenta una gran serra addossata a destra ad un muro della casa di John Clark. Due or tre larghi scalini danno accesso per una larga porta alle stanze terrene della casa. Due tavoli rustici e sedie di legno sono a destra ed alla sinistra della scena, presso i vetri in fondo ed a destra, piante. La gran porta in vetri della serra situata nel mezzo, è aperta. Al di là della serra che dà nel giardino si scorge a destra nel fondo il gran cancello che serve di entrata, poi il muro di cinta che va da destra a sinistra e su questo lato sinistro lo spigolo e la porta d’entrata della fabbrica di John Clark. Al di là del muro, paesaggio di campagna invernale. È una fredda ma bella giornata d’inverno. |

ACT ONE The scene is of a large conservatory against the wall of John Clark’s house on the right; three wide steps provide access through a large doorway to the ground floor rooms of the house. Two simple tables and wooden chairs are located at the right and the left of the stage, plants in the background near the glass wall and at right. The main door in glass of the conservatory, situated in the centre, is open. Beyond the conservatory, which opens onto the gardens, the main gate appears on the right which functions as the entrance; the garden wall leads from right to left and on the left side, the corner and entrance door of John Clark’s workhouse. Beyond the wall, a wintery countryside. It is a cold but beautiful winter’s day. | |

| (Giorgio è assiso al tavolo leggendo. John discende vivamente i gradini della porta a destra, va sino alla porta della serra e guardando dalla porta della fabbrica grida irritato) John Charley! Holger! Qualcuno, orsù che diamine! (i due servi accorrono timorosi dalla fabbrica) La signora ha finito? |

(George, Jenny’s uncle, is seated at table reading. John quickly descends the steps from the door at the right and going up to the conservatory door calls out angrily toward the workhouse) John Charlie! Holger! Somebody, come on! What the devil! (two servants nervously run from the workhouse) Has her ladyship finished? | |

| Un servo (timidamente) Quasi. |

A servant (timidly) Almost. | |

| John Ditele che si spicci. Io l’aspetto. |

John Tell her to hurry up. I’m waiting for her. | |

| (I due servi si affrettano verso la fabbrica: John passeggia di cattivo umore) | (The two servants hurry to the workhouse: John walks about in a bad mood) | |

| Ubbie di femine! Gire a pagar la gente de la fabbrica Di propria mano, perché la vigilia Ricorre del Natal! Mia moglie esagera. Troppa bontà è nociva! Essi lavorano. Io pago e basta. Così me li guastano! |

Women’s ideas! Going around to pay the workers personally, because it is Christmas Eve again! My wife goes too far. Too much kindness is harmful! The employees labour. I pay and that is enough. They’ll ruin them for me! | |

| Giorgio Tu non li guasti certo! |

George You surely won’t ruin them! | |

| John Voi, buon quacquero, Vedete il mondo a modo vostro! Io sembrovi forse crudel? |

John You, my good Quaker, see the world in your own way! I suppose I seem cruel to you? | |

| Giorgio Che importa il mio giudizio! Un giusto sei per la legge degli uomini E ciò ti basta! |

George What does my opinion matter. According to the laws of man, you are just and that’s enough for you. | |

(John volge furiosamente le spalle a Giorgio mentre dal fondo arrivano Jenny ed Henry. Henry corre subito a Giorgio che lo prende sulle ginocchia) |

(John furiously turns away from George while from the background arrive Jenny and Henry. Henry runs immediately to George who sits him on his knees.) | |

| John (scorgendo Jenny) Eccovi alfin, uditemi. Lord Klifford qui desidera Sostar, passando, con gli amici suoi Che a caccia l’accompagnano. Il tutto a preparar pensate voi. Bisogna ben riceverlo! Bisogna ben ricevere Di Lord Maire il nepote e fargli festa, Ch’è grande onor per noi s’ei qui s’arresta. (Jenny s’inchina e fa per entrare in casa dalla gran porta) Un motto ancor. (quasi cercando il nome che non si ricorda) Quel ... Tom, non ha pagato? |

John (seeing Jenny) Here you are at last. Listen to me. Lord Clifford is passing through and wishes to stop here with his friends who are hunting with him. Look after all the preparations. He has to be well-received! The Lord Mayor’s nephew must be well-received and feasted properly, It’s a great honour for us if he should stop by. (Jenny curtsies and is about to go into the house by the main door) One more thing. (as if looking for a name he cannot recall) Has that ... Tom ... made any payment? | |

| Jenny Ei non deve pagar che domattina. |

Jenny He doesn’t have to pay until the morrow. | |

| John Uhm! Ha l’aria ben meschina! Ricco non è sicuro... Ha un fare incerto. |

John Uhm! He has a miserable appearance! He’s surely not wealthy ... He has a dubious occupation. | |

| Giorgio Ei Lord Klifford per te non vale certo! (John fa un passo, irritato, come se volesse rispondere a Giorgio poi gli volge bruscamente le spalle, esce dalla serra e va via) Henry Uh! L’orso si allontana! Ridersi può. Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah! suona la campana. |

George For you, even Lord Clifford is not worth much! (Annoyed, John makes a move as if he wants to answer George, but then abruptly turns away, leaves the conservatory and departs) Henry Uh! The old bear is leaving! One may now laugh. Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha! Ah! the bell is ringing. | |

| (Henry corre verso il fondo guardando l’uscita degli opererai dalla fabbrica. Dopo il loro coro escono in fretta in disordine. Chatterton compare. Henry corre allegro a lui) | (Henry runs toward the back of the garden watching the exit of the workers from the workhouse who are leaving pell-mell. Chatterton appears. Henry runs quickly to him) | |

| Alfin! Buondi. | Good day! At last! | |

| Chatterton Buondi. |

Chatterton Good day. | |

| Henry Deggio parlarti. |

Henry I must speak with you. | |

| Chatterton (sorridendo) Sul serio! Un bacio. |

Chatterton (smiling) Indeed! A kiss. | |

| Henry (corre ad abbracciarlo e baciarlo) Toh! |

Henry (runs to embrace him and kisses him) There! | |

| Chatterton Sto ad adscoltarti! |

Chatterton I’m listening! | |

| Henry Diman del Natale ricorre la festa E liete sorprese tal giorno m’appresta. Ognuno il suo don m’ha già preparato |

Henry Tomorrow is the feast of Christmas And I’m ready for pleasant surprises that day. Everyone has surely prepared a gift for me | |

| E a me, come gli altri, tu pur hai pensato! Or veh, di buon’ ora quel dono lo vo’ E a l’uscio a destarti domani verrò! Verro! (Chatterton è interdetto) |

And you, like the others, have thought of me too! Now then! I want that gift early And I’ll come to the door to wake you! I’ll be there! (Chatterton is dumbfounded) | |

| Giorgio (severo ad Henry) Henry!! |

George (sternly) Henry!! | |

| Chatterton (a Giorgio) Perché sgridarlo? (poi ad Henry sorridendo) Vieni! Destami! (Henry porge l’orecchio per accertarsi del suono del corso) |

Chatterton (to George) Why yell at the boy? (then smiling at Henry) Do come! Do waken me! (Henry listens checking for the sound of horses) | |

| Henry Già risuonano i corni! È d’uopo correre A prevenir Jenny! (gridando verso la casa) Son essi! Arrivano! (esce correndo dalla gran porta) |

Henry There! The hunting-horns are resounding! We need to run to forewarn Jenny! (yelling toward the house) They’re here. They’re coming! (he runs out through the main door) | |

| Chatterton Di chi parla? Chi giunge? Giorgio Alcuni giovani, Dei Lord nel gire a caccia qui fan sosta. |

Chatterton Of whom does he speak? Who is arriving? George Some young men, some lords out hunting are making a stop here. | |

| Chatterton Usciamo allor! Degli uomini la vista m’è incresciosa. |

Chatterton Let us leave then! The sight of these men is not to my liking. | |

| Giorgio Orvia, lontani son essi ancor. Calmati. Vien qui. Turbato sei! Dammi le mani. Che hai? |

George Come now, they are still a long way off. Calm yourself. Come here. You’re upset. Give me your hands. What is it? | |

| Chatterton Scrissi una lettera che molto mi costò! |

Chatterton I once wrote a letter which cost me much! | |

| Giorgio Tu se’ spossato! Le veglie ti consumano! E viver conti molto in tale stato? |

George You are weary! The evenings are wearing you out! Does life mean much in this condition? | |

| Chatterton Il men che sia possibile! |

Chatterton Not very much at all! | |

| Giorgio Sei folle! E che, non hai forse una meta? Inutile è la tua vita ormai? |

George You’re a fool! Do you have any purpose in life? At this point is your life not useless? | |

| Chatterton La mia vita è un martirio. Eppure la mia meta Era il sogno più candido che mai sognò un poeta! Ricomposi l’antica favella tutta mistica, pura infantil, E le vecchie leggende, e le vecchie leggende con quella Ho cantato a un troviero simil. Il Re Aroldo e Guglielmo evocato Ho nel semplice antico parlar, E con esso quel mondo obliato Io potei de la tomba destar! E con esso quel mondo obliato potei de la tomba destar! |

Chatterton My life is a martyrdom. And yet my goal was the most pure dream that a poet ere dreamt! I restored the archaic tongue, wholly mystical, pure naïve, And with it the old legends, the old legends I intoned like a troubadour. King Harold and William I evoked in the simple language of old, and with it I could rouse from the tomb that forgotten world! And with it I could rouse from the tomb that forgotten world! | |

| (to George) Vedeste Mistress Clark? Son qui, s’appressano. Partiam. |

(to George) Have you seen Mistress Clark? They’re here, they’re approaching. Let’s go. | |

| Giorgio (mettendo il cappello che è su di un tavolo poi dice guardando all’interno) Si vieni. Distrar dei lo spirito. Lasciamo ora Sir John tutto alla gioia D’inchinarsi a Lord Klifford! |

George (putting on his hat which was on the table, looking inside says) Yes, do come along. Take your mind off things. Let us now leave to Sir John all the joy of bowing to Lord Clifford! | |

| Chatterton Che diceste? Lord Klifford? |

Chatterton What is that you said? Lord Clifford? | |

| Giorgio Si. |

George Yes. | |

| Chatterton È lui che vien! |

Chatterton Is he the one arriving! | |

| Giorgio Ei stesso. |

George The very one. | |

| (John scende frettuloso, chiama i due servi della fabbrica e con essi va ad aprire il gran cancello) | (John hurriedly comes, calls the two servants from the workhouse and goes with them to open the main gate) | |

| Chatterton Maledizion! Perché mi riteneste? Come sfuggirlo adesso! |

Chatterton Damn it all! Why did you hold me back? How can I escape him now! | |

| Giorgio Lo cononsci? |

George Do you know him? | |

| Chatterton Purtroppo! |

Chatterton Only too well! | |

| Giorgio Ebben paura hai d’un amico? |

George Then you are afraid of a friend? | |

| Chatterton Voglio fuggir. Voglio fuggir. |

Chatterton I want to escape. I want to escape. | |

| Giorgio Alle porte giungono già! |

George They’re already at the doors! | |

| Chatterton (sdegnato) Su ... fiato ai corni ... forte. (colpi di scudiscio al di là del muro e risate allegre) Halalli! Hallali! L’hanno scovato il cignal solitario! |

Chatterton (indignant) Come on ... the sound of the horns ... hurry. (cracks of riding whips outside the wall and cheerful laughter) Halalli! Hallali! They have flushed out the solitary wild boar! | |

| (Jenny ed Henry appaiono) | (Jenny and Henry appear) | |

| John Oh! quale onore Mylord ... Signori! Quale onore! |

John Oh! Such an honour my lords ... Gentlemen! Such an honour! | |

| Lord Klifford Buondì, John, Buondì. La gioia che nel vedervi, Mistress Clark, io sento Ridir vorrei ma ... (s’interrompe scorgendo Chatterton) Toh! Chi vedo! È desso! (Klifford corre allegramente a Chatterton aprendogli le braccia) Tu Chatterton! Ma si ... Qui, qui, amico mio. Ma che? Si freddo! Ora i tuoi vecchi amici, perché celebre sei, più non conosci! |

Lord Clifford Good day, John, good day! The joy of seeing you, Mistress Clark, that I feel I wish I could tell you again, but ... (noticing Chatterton, he breaks off) Whom then do I see! ‘Tis he! (Clifford runs quickly to Chatterton taking him by the arms) You, Chatterton! But yes ... Here, my friend is here. But how can it be? So cold! You forget your old friends now because you are famous! | |

| Chatterton Klifford! Klifford (a John) Perché voi non mi preveniste? |

Chatterton Clifford! Clifford (to John) Why didn’t you warn me? | |

| John (confuso) Di lui, Mylord, nulla sappiam. Condotto fu qui da un suo parente ... Sotto il nome di Tom prese una stanza e il resto tacque. Chi credere potea ch’intimo fosse di vostra signoria! |

John (confused) We knew nothing about him, my lord. He was brought here by one of his family ... He took a room as Tom and for the rest he said nothing. Who would have thought he was a close friend of your lordship. | |

| Klifford Studiammo insieme in Oxford Ma quest’è tutto un romanzo! Ah! Ah! Ah! (a Chatterton) Tu incognito! |

Clifford We studied together at Oxford But that is just a mediaeval tale! Ha! Ha! Ha! (to Chatterton) You, incognito! | |

| Signori, vi presento ... | Gentlemen, I present to you ... | |

| Chatterton Taci! |

Chatterton Do be quiet! | |

| Klifford ... Tommaso Chatterton, poeta, Il celebrato autore de l’Aroldo. (a Chatterton presentandogli i due Lord) Ed ecco due ferventi ammiratori tuoi. (poi volto ai Lord ed a Jenny dice additando Chatterton) Suo padre è un ricco capitano di mare. |

Clifford ... Thomas Chatterton, poet. The celebrated author of Harold. (to Chatterton while presenting two lords to him) And here are two of your fervent admirers. (turning to the lords and Jenny while pointing to Chatterton) His father is a rich sea captain. | |

| John (a Jenny) Or via, gentile convien mostrarsi subito a l’amico di Mylord, ed offrirgli un’altra stanza. |

John (a Jenny) Go on, it would be good to be nice to my lord’s friend right now, and offer him a different room. | |

| Jenny Ei povero non è com’io credea! |

Jenny He’s not poor as I thought him to be! | |

| Klifford (osservando l’abito di Chatterton) Ma! ti veggo abbrunato! Che ... tuo padre?! (John affretta i domestici a preparare le tavole) |

Clifford (observing Chaterrton’s clothes) But I see that your in mourning dress! Who ... your father? (John hurries the staff along to prepare the tables) | |

| Chatterton Ei più non è! |

Chatterton He is no longer! | |

| Klifford Perdon se ridestai tal duol! Egli era vecchio! Eccoti erede. |

Clifford Pardon me if I mocked your sorrow! He was an old man! So now you’re the heir. | |

| Chatterton (sorridendo amaramente) Di quanto gli restava. |

Chatterton (smiling bitterly) Of whatever remained. | |

| John (indicando le tavole ed inchinandosi) Miei Signori, se ci fate l’onore. |

John (pointing to the tables and bowing) My lords, if you would do us the honour. | |

| Klifford (a John) Certamente! |

Clifford (to John) Certainly! | |

| I Lord Tu se’ dei nostri. Klifford (Chatterton cercando rifiutare) E che! Tu vuoi fuggirmi? Orso! No, dei restar con noi! |

The Lords You will join us. Clifford (Chatterton trying to refuse) What! You want to escape me? Old grump! No, you must stay with us! | |

| (Jenny, Chatterton, Klifford, Henry e gli altri Lord siedono alle due tavole. I due servi e John servono. Giorgio è nel fondo in piedi osservando Klifford.) | (Jenny, Chatterton, Clifford, Henry and the other lords sit down at the two tables. The two servants and John serve. George stands in the background watching Clifford.) | |

| (a Jenny) Dunque incognito ne venne Qui Tommaso ad albergar. Ben felice è ‘l vate nuovo Se a voi presso può restar |

(to Jenny) So Thomas was unknown when he came here as guest. Our new bard will be quite happy If he may remain with you. | |

| Jenny (timida e confusa) Mio Signor! |

Jenny (shy and confused) My lord! | |

| Klifford Timida tanto esser sempre non convien ... Voi si bella e si gentile! (a Chatterton) Via, correggila tu al men! |

Clifford You must not always be so bashful ... You are so beautiful and polite! (to Chatterton) Come on, at least admonish her! | |

| Jenny O Mylord. O Mylord, ve ne scongiuro, più non dite! |

Jenny O my lord. O my lord, I beseech you, say no more! | |

| Klifford (a Jenny) Orvia! Orvia, perché bella diss’io vi turbate? (a Chatterton) Di’ su, bella essa non è? (ridendo) Di’ su, bella non è! |

Clifford (to Jenny) Come! Come! Why get upset when I call you beautiful? (to Chatterton) Tell me, is she not a beauty? (laughing) Come on, say it, is she not a beauty? | |

| Giorgio Dacché sei giunto, mio bel giovane, Un motto non dicesti qui che inutile... E di troppo non fosse! |

George Since you arrived, my handsome lad, You’ve made nothing here but useless quips ... And all were quite unnecessary! | |

| Klifford Oh! Che selvatico animale è costui? |

Clifford Oh! What wild animal is this? | |

| John Perdono! È un quacquero! |

John I beg your pardon! He is a Quaker! | |

| Klifford Un quacquero! (ridendo) Ah! Ah! Ah! |

Clifford A Quaker! (laughing) Ha! Ha! Ha! | |

| I Lord Un quacquero! (tutti ridendo) Ah! Ah! Ah! |

The Lords A Quaker! (all laughing) Ha! Ha! Ha! | |

| Klifford Davver? Tal selvaggina non cacciamo sinora! |

Clifford Indeed? We’ve not hunted such game till now! | |

| Chatterton Klifford, dà tregua al labbro loquace! Quel vecchio venerando rispettate! |

Chatterton Clifford, give your talkative mouth a rest! Have some respect for the elderly man! | |

| Klifford (a Chatterton) Ih! Ih! Che furia! Ti scaldi! (scherzando a Jenny) Per punirlo, il thé, Mistress Jenny, non gli versate. (con tenera galanteria) Perché severa e rigida sempre, sempre così, Signora, vi mostrate? Perché quando rivolgonsi Dolci parole a voi ... Dolci parole a voi, non ascoltate? |

Clifford Hi! Hi! Such anger! You’re getting quite heated! (joking with Jenny) To punish him Mistress Jenny, don’t pour him his tea. (with tender courtesy) Why always serious and reserved, Do you always present yourself thus, my Lady? When kind words are addressed to you When kind words are addressed to you Why do you not listen? | |

| John (a Giorgio) Volete compromettervi Col nepote del Maire! è una pazzia! |

John (to George) Do you wish to get in trouble with the Lord Mayor’s nephew! It’s madness! | |

| Giorgio (a John) Ve ne prego lasciatemi! |

George (to John) Please, leave me alone! | |

| Klifford Perché ... . |

Clifford Why ... . | |

| Klifford (alzandosi, un po’ eccitato dal vino) John, dite che ci apprestino i cavalli. |

Clifford (rising to his feet, stimulated a little by the wine) John, have the horses made ready for us. | |

| John All’istante, Mylord. (esce frettoloso dalla serra e scompare dal cancello) |

John Immediately, my lord. (he leaves the conservatory in haste and exists through the gate) | |

| Klifford (afferrando un bicchiere) L’ultima coppa io bevo (a Jenny) in vostro onor. Che! ... non bevete? (appressandosi a lei) Dunque spe me non v’ha? |

Clifford (taking up a glass) I drink a final glass (to Jenny) in your honour. What! ... You’re not drinking? (moving toward her) So, there’s no hope for me? | |

| Jenny (sprezzante) Non vi comprendo, Mylord! |

Jenny (disdainful) I don’t understand you, my lord! | |

| Lingston e Strafford Il vin più tenero lo rende! (ridendo) Ah! Ah! Ah! |

Lingston and Strafford The wine makes him more loving! (laughing) Ha! Ha! Ha! | |

| Gli altri Lord (ridendo) Ah! Ah! Ah! |

The other Lords (laughing) Ha! Ha! Ha! | |

| Klifford Almeno di baciar la vostra mano Dato mi sia pria di partir! (cercando prenderle la mano a Jenny) |

Clifford At least it may be permitted me to kiss your hand before departing! (attempting to take Jenny’s hand) | |

| Jenny (ritraendola vivamente) Signor! |

Jenny (withdrawing it firmly) Sir! | |

| Chatterton No! Basta Klifford! Scordaste dove siete! e che una donna onesta si rispetta! |

Chatterton No! That’s enough Clifford! Have you forgotten where you are and the respect due an honourable lady! | |

| Klifford Ma che c’è? Che ti piglia? Non capisco! |

Clifford What’s wrong? What is bothering you? I don’t understand! | |

| Chatterton Non capite? Volete che nel bosco v’attenda al ritorno dalla caccia! |

Chatterton Don’t you understand? Do you wish me to wait upon you in the woods when you return from the hunt! | |

| Klifford Al ritorno! nel bosco! (dando in una risata) Perdonami! Io cieco ero davver! Che commedia! Ora comprendo. Tu qui solo incognito! Il suo rigor. Il tuo furor! |

Clifford On my return! In the woods! (bursting into laughter) Pardon me! I was truly blind! What a farce! Now I understand. You here alone incognito! Her reserve. Your anger. | |

| Chatterton (si slancia verso Klifford ma è ritenuto da Giorgio) Ah! Rettile! |

Chatterton (lunges at Clifford but he is restrained by George) Base coward! | |

| Klifford Perdonatemi se venni a disturbarvi! |

Clifford Excuse me if I have troubled you! | |

| I Lord (ridendo) Piacevole è la storia! Piacevole è la storia! (tutti s’incamminano verso l’uscita in fondo) |

The Lords (laughing) A delightful tale! A delightful tale! (all move toward the door in the background.) | |

| Lingston e Stafford (ironico a Klifford) Del cor molci la piaga! |

Lingston and Stafford (to Clifford with irony) You are pouring balm on wounded hearts! | |

| Klifford (ridendo) Andiam! |

Clifford (laughing) Let us go! | |

| Lingston e Stafford Hai perso la scommessa! Paga! (Tutti escono dal fondo.) |

Lingston and Stafford You lost the wager. Pay up! (All depart at back.) | |

| Jenny (in preda alla più grande agitazione parla irritata senza mai guardare Chatterton volgendosi a Giorgio.) |

Jenny (with the greatest agitation Jenny speaks while facing George without ever looking at Chatterton.) | |

| Gli amici suoi perché il signor non segue? | Why doesn’t my lord go with his friends? | |

| Chatterton Amici miei non sono. |

Chatterton They are not my friends. | |

| Jenny Eppur ben meglio Di noi conoscon essi i suoi progetti Ed il suo stato, e noi tutto ignoriam! |

Jenny And what’s more they know his plans better than we do and his estate as well, and we know nothing! | |

| Chatterton Essa li udì! O tortura! |

Chatterton She heard all that! O what torture! | |

| Giorgio (a Jenny) Orsù ti calma. |

George (to Jenny) Come now, calm yourself. | |

| Jenny (sempre più agitata a Giorgio) Richiedete al signor, poiché l’impone Lo sposo mio, se una migliore stanza Desidera. |

Jenny (to George, still more agitated) Ask his lordship, since my husband insisted, if he wishes a better room. | |

| Chatterton No. Quella chè sin’ora m’ebbi a miei disegni basta. |

Chatterton No. The one I’ve had till now is enough for my plans. | |

| Jenny (con violenza) Allor che tal disegni celansi con cura Colpevoli esser ponno. |

Jenny (with fury) What plans are you then hiding so carefully they could be guilty. | |

| Chatterton O Dio! Colpevoli! Un nuovo strazio al mio martiro aggiunto! |

Chatterton O God! Guilty! Another torment added to my martyrdom! | |

| Jenny Ma qual donna sarà più rispettata S’io non la sono? Tutta una vita casta Di cristiana, di sposa onorata. Da l’insulto a difendermi non basta. Proteggetemi voi! Pieno d’onore M’appare il mondo e sola son quaggiù. Risparmiate al mio cor nuovo dolore. Deh! fate ch’essi non ritornin più! Che non ritornin più! |

Jenny If I am not respected, what woman will be? A life entirely chaste, a Christian, an honourable wife. It is not enough to defend me from insult. Protect me! People seem very honourable to me and yet I am alone here. Save my heart from yet more pain. Ah! Make sure they return no more! That they return no more! | |

| Giorgio Essi. Chi? |

George They. Who? | |

| Jenny Tutti. Tutti. Un altro alloggio Può trovare il signor. La sua ricchezza. |

Jenny All, all of them. The gentleman can find another dwelling with his riches. | |

| Chatterton Ah! Basta. Basta così! Ne’ pieghi del sudario Seco portò morendo il padre mio La ricchezza che ancor qui l’amicizia Mi valse di que’ Lord! Più non son io Che un operaio di libri, Che un operaio di libri! Accordatemi sol Sino a diman, Signora, e partirò. Il tempo di vergar sol poche pagine Che debbo! io vi scongiuro Altro non vò! |

Chatterton Ah! Stop it. Enough! My dying father carried away with him in the folds of his shroud the wealth that still brings me friendship with those lords! I am nothing more than one who writes books, than one who writes books! Grant me only till the morrow, my lady, and I shall depart. The time to write only a few pages that I must! I implore you I seek nothing else. | |

| (Jenny che è andata commovendosi alle parole di Chatterton dice congiungendo le mani quasi col pianto agli occhi) | (moved by Chatterton’s words, clasping her hands with almost tears in her eyes, Jenny says to him) | |

| Jenny Perdon! Perdon! |

Jenny Forgive me! Forgive me! | |

| Chatterton A l’opra andar deggio! Voi siete buona! Voi siete buona! Addio signora! Addio! Addio! (si allontana vivamente dal giardino) |

Chatterton I must start to work! You are kind! You are kind! Goodbye, my lady. Goodbye. Goodbye. (he leaves the garden quickly) | |

| (Giorgio che li ha fissati entrambi durante questa scena si appressa a Jenny che nasconde il volto lacrimoso sul di lui petto.) | (George, who has watched them both during this scene, approaches Jenny who hides her tearful face on his chest.) | |

| ATTO SECONDO La scena è divisa in due. Il lato sinistro rappresenta la cameretta di Chatterton povera e nuda. Il lato destro un salone comune della casa di John Clark. A destra di questo salone, sul davanti, tavolo con l’occorrente per scrivere e due sedie accanto ad esso. Sul lato destro una porta che conduce agli appartamenti di Jenny e di John. A destra nel fondo un alto camino e da sinistra porta comune. Tra il camino e la porta un canterano di quercia scolpita. Sul muro che divide le due stanze una finestra, e poi, sul davanti, una scaletta di tre o quattro gradini conduce alla porta della camera di Chatterton. Il palcoscenico sul lato sinistro sarà rialzato d’un metro. Tutto il fondo di questa stanzetta sarà occupato da una larga finestra dalla quale alla luce di un’alba livida si vede il paesaggio coperto di neve caduta nelle notte. Sul muro a sinistra un misero letto di ferro, sul muro di divisione, dopo la porta, un caminetto spento. Sul davanti in faccia al pubblico un tavolo coperto di libri e di carte sul quale arde una lucerna ad olio. |

ACT TWO The scene is divided in two. The left side shows Chatterton’s poor, spare little room. On the right is the main hall of the house of John Clark. At the right of this hall, in the front, is a table with writing materials and two chairs beside it. On the right side, a door which leads to the apartments of Jenny and John. On the right in the background a fireplace and to the left a common doorway. Between the fireplace and the door, a chest of drawers of carved oak. On the wall that divides the two rooms, a window, and in the front, a stairway of three or four steps leading to the door of Chatterton’s room. The stage on the left side is raised one metre. The entire background of this small room is filled with a large window through which the countryside covered in the night’s snowfall can be seen in the grey light of dawn. On the wall to the left a simple iron cot, on the dividing wall beyond the door, a small fireplace whose fire has gone out. At the front of the stage nearest the audience a table covered with books and papers on which stands a lighted oil lamp. | |

| Intermezzo sinfonico con Coro | Symphonic Intermezzo with chorus | |

| (A metà del preludio una campana suona ed il coro di donne dietro la tela canta.) | (A bell sounds at the midpoint of the prelude and a women’s chorus sings behind the curtain.) | |

| A Dio sia gloria ed alla terra pace una Vergine eletta concepì. Il verbo è fatto carne; amor la face accese e l’odio umano si assopì. A Dio sia gloria ed alla terra pace. |

Glory to God and peace on earth A chosen Virgin has conceived. The Word is made flesh; With love the torch burns bright and man’s hatred is allayed. Glory to God and peace on earth. | |

| (La tela si alza Chatterton dorme poggiato al tavolo) | (Chatterton is asleep at the table as the curtain rises) | |

| (Si alza, va a mettere il mantello che è sul letto e poi siede al tavolo prende un foglio e legge) | (He awakes, puts on the cloak that was on the bed and then seated at the table takes up a page and reads.) | |

| Chatterton Stanco spossato arresta il triste pellegrin nel bosco il suo cammin. Le vesti a lembi cadono ed ha il suo volto affranto solchi d’antico pianto! Cerca l’estremo letto per riposarvi l’ossa. Egli cerca una fossa Fredda siccome l’umida terra che il coprirà E l’oblio gli darà. E l’oblio gli darà. Perché impresi a narrar le sue sventure chi si cura di cio? Ma che!... Vaneggio!... Oh quanta era pietà ne l’attristato volto quando a me chiedea perdon! Jenny! Jenny! S’ella m’avesse amato! Amor! Amor dimando! Ed io chi sono?! Senza pan... senza tetto... a termin fisso. Deggio spremer l’idea dal mio cervello con la tema d’un carcere! E a quest’ora non posso più! non posso più! Un’idea più qui non ho! più nulla! Ho fame!! Ho fame!! Non saria meglio di troncar codesta abbietta vita di duol? Che più mi resta! Tu sola a me rimani o Poesia. Veste di Nesso ch’io non so strappar. Quel po’ che resta de la vita mia Sino il rantolo estremo ti vo’ dar! L’ultimo canto de la mente stanca o dea severa a te senvolerà. E canterò codesta neve bianca come il sudario che m’avvolgerà, che m’avvolgerà!! (cade piangendo sul letto) |

Chatterton Weary, exhausted, the unhappy pilgrim stops on his journey in the darkened wood. His garments fall in shreds and his anguished face is lined by the tears of yesteryear! Seeking the bed of his body’s final rest, he searches for a grave Cold as the dank earth that covers it and the escape it grants. And the escape it grants him. Why did I begin to tell of his misfortunes who would care about them? Nothing of the kind! Nonsense! Oh, what pity there was in that sad face when she asked pardon of me! Jenny! Jenny! If she had only loved me! Love! I want love! And I, who am I?! Without food ... homeless ... and only a brief life. I must rack my brains for an idea with a prison theme! And at this moment I can do no more! I can do no more! I don’t have another idea! Nothing more! I’m hungry! I’m hungry! Would it not be better to end this abject life of sorrow? What else is there for me! You alone, oh Poetry, remain mine. The shirt of Nessus that I cannot tear off. That little which remains of my life I give unto you till the final rattle of death! The last lyric from an exhausted mind, oh goddess severe, will fly to you. And I shall sing of this white snow as the shroud which will enfold me, which will enfold me! (falls on the bed weeping) | |

| (Il servo entra, va ad accendere il fuoco e poi sorte subito. Henry entra) |

(The servant enters, lights the fire and leaves immediately. Henry enters) | |

| Henry Son certo ch’ei dorme. Ancor non uscio. (va alla camera di Chatterton sale i gradini e picchia) |

Henry I’m sure he is asleep. He hasn’t come out yet. (he goes to Chatterton’s room, goes up the steps and knocks) | |

| Chatterton (balzando) Chi batte? |

Chattetton (jumping to his feet) Who is knocking? | |

| Henry (ingrossando la voce) Indovina! Chatterton Chi è? |

Henry (altering his voice) Try to guess! Chatterton Who is it? | |

| Henry Via, son io! |

Henry Come on, ‘tis I! | |

| Chatterton Henry! |

Chatterton Henry! | |

| Henry Su, poltrone. Ti scuoti. (Chatterton apre. Henry entra) Buondì. (si arresta, sorpreso) Toh! ancor arde il lume! Che freddo fa qui! Perché non fai fuoco? |

Henry Hurry up, lazy-bones. Rouse yourself. (Chatterton opens the door. Henry enters) Good day. (he stops in surprise) Here! The lamp is still burning! It’s so cold in here! Why don’t you make a fire? | |

| Chatterton (confuso) Or esco ... non cale. |

Chatterton (vague) I’m just going out ... I don’t care. | |

| Henry (andando verso il letto dove depone i pacchi) I doni mostrarti vo’ pria del Natale. La scatola a dipingere vien da Jenny. Il soldato Da Giorgio e John diè l’anfora. E tu? E tu che in hai serbato. |

Henry (going over to the bed where he places the packages) I want to show you my gifts before Christmas. The paint box comes from Jenny. The soldier from George and John gave the amphora. And you? What have you put away. | |

| Chatterton Il mio regalo! |

Chatterton My present! | |

| Henry È qui? Dammelo. |

Henry It is here? Give it to me. | |

| Chatterton (andando verso il tavolo) Si ... ei pensai! È questo libro ... prendilo. A Jenny lo darai. Perché quando comprenderlo potrai lo renda a te. |

Chatterton (going toward the table) Yes ... I thought about it! It is this book ... take it. You shall gave it to Jenny. So that when you are able to understand it she will give it to you. | |

| Henry Grazie! (lo apre curioso) Oh! le belle immagini. Di, vuoi mostrarle a me. Ma ... qui fa freddo! Seguimi laggiù ... Non ricusar ... (raccoglie i giocattoli sul letto, poi prende per mano Chatterton e lo forza a discendere nel salone Là... là.... presso a quel tavolo tutto mi dei spiegar (additando il libro) Ei si noma? |

Henry Thank you! (he opens it inquisitively) Oh! what beautiful pictures. Tell me, would you show them to me. But ... it is so cold in here! Come down with me ... Don’t refuse ... (collecting the toys from the bed, he takes Chatterton’s hand and makes him go down into the hall) There ... there ... at that table, you must explain everything to me (pointing to the book) What’s it called? | |

| Chatterton La Bibbia. |

Chatterton The Bible. | |

| Henry Dimmi l’hai fatto tu? |

Henry Tell me, did you write it? | |

| Chatterton (sorridendo) No! No! |

Chatterton (smiling) No! No! | |

| Henry Ci son belle istorie? |

Henry Are there any good stories in it? | |

| Chatterton Tante! |

Chatterton Many! | |

| Henry Vediamo sù. (apre a caso il libro e legge) D’acqua e di pane li provvide Abramo e poi li discacciò. Via pel deserto di Beerseba ad errare Agar si prese col figluolo Ismael. I dì passaro e l’acqua e ‘l pane vennero a mancar. Agar sentia come uno strazio immenso non per se ma pel figlio. E quando un giorno cader lo vide stanco ed affamato presso un cespuglio il misero depose; poi lunge andò gemendo e disse a Dio! Ch’i’ nol vegga morire il figlio mio! |

Henry Let us see. (he opens the book at random and reads) Abraham gave them water and bread and sent them away. Hagar departed and wandered In the wilderness of Beerseba with her son Ishmael. Days passed and when the water and bread were gone, Hagar bore it as an immense affliction not for herself but for her child. And when one day she saw him fall weak and hungry she laid the poor child by a shrub tree; then she went a good way off weeping and said unto God Let me not look upon the death of my son! | |

| (Chatterton dà in uno scoppio di pianto e fugge dalla porta del fondo) | (Chatterton breaks into tears and dashes through the door in the background) | |

| Che hai? Tom di’, che hai? Oh, il cattivo! Tu piangere mi fai! |

What is it? Tom, tell me, what is the matter? Oh, you bad thing! You have made me cry! | |

| (Jenny e Giorgio entrano) Giorgio Perché piangi? Perché. |

(Jenny and George enter) George Why are you crying? Why? | |

| Jenny Che hai? |

Jenny What’s the matter? | |

| Henry Non so ... leggevo questa novella a Tom quand’egli a un tratto È fuggito piangendo. (Giorgio prende il libro e legge) |

Henry I don’t know ... I was reading this story to Tom when suddenly he ran away crying. (George takes the book and reads it) | |

| Giorgio E chi ti diede questo libro? |

George And who gave you this book? | |

| Henry È il suo dono pel Natale! |

Henry It is his gift for Christmas! | |

| Giorgio Va, bimbo mio. Scordati i suoi fastidi Sereno ei tornerà. Va, giuoca, ridi. |

George Go on, my child. Forget about his problems. He’ll return in calmer mood. Go now, play and laugh. | |

| Jenny Deggio il dono accettar? |

Jenny Must I accept the gift? | |

| Giorgio Chi rende al povero cio ch’egli offre, l’umilia! |

George One who returns what a poor man offers, humiliates him! | |

| Jenny È vero! (volta a Giorgio dice esitando) Ditemi, voi conoscete i scritti suoi? Mirabili son essi inver? |

Jenny That’s true! (turning to George, she says hesitating) Tell me, you know his writings, don’t you? Are they not truly wonderful? | |

| Giorgio Potente ingegno affermasi. |

George They give proof of serious talent. | |

| Jenny Giovintanto! Ah, voi dir più non volete! Perché? Quant’io l’ammiri non sapete. Stamane ancor chiesi perdono a Dio Del mal che ieri gli fece il parlar mio! |

Jenny Oh, very helpful! So you wish to say no more! Why? You know not how much I admire him. Again this morning I asked pardon of God For the harm my words did him yesterday! | |

| Giorgio Un angiol sei! Ma datti pace. A Klifford ieri svelai di Tom la misera storia. Ei commosso Lord Maire giurò di flettere; Ed oggi al suo castel lo condurrà Dove al fin pace e asilo ei troverà. |

George You are an angel! But be at peace. I revealed Tom’s sad story to Clifford yesterday. Much moved, he swore to convince the Lord Mayor; And today he will take him to his estate Where he will finally find peace and shelter. | |

| Jenny Benedetta dal ciel per sempre sia la casa ove tranquillo ei dee posar poichè conforto or la dimora mia al suo cor travagliato non può dar. Sorridan pie le stelle al viandante e le siepi rammentino al suo cor che mentre ei volge altrove il passo errante v’ha chi sempre per lui prega il Signor. |

Jenny May heaven bless forever the house where he may find tranquillity since my home cannot now give his troubled heart comfort. May the merciful stars smile upon the wayfarer and the hedgerows remind his heart that while he turns his roving step elsewhere he has one who prays the Lord for him always. | |

| Giorgio Tu se’ buona Jenny. Ma troppo invero ardor dimostri per chi t’è straniero! |

George You are kind, Jenny. But you show indeed too much ardour for one who is a stranger to you! | |

| Jenny Stranier. Stranier per me? No! Stranier! Per me! No ... per la legge umana che Dio stesso dettò forse compiangere non poss’io, cristiana lui che ‘l compianto merita! Straniero egli, perché, perché? Candido ha’l core come fanciul. Tutta purezza è l’animo mite nel suo dolor, mite nel suo dolor non sa imprecar ne gemere. |

Jenny A stranger. A stranger to me? No! Stranger! To me! No ... by the law which God Himself gave us May I, as a Christian, not weep for him who is worthy of grief! He a stranger? why, why? He has the candid heart of a child. His nature is all purity gentle in his sorrow, gentle in his sorrow he knows not how to curse nor complain. | |

| (Jenny fugge turandosi le orecchie colle mani. Giorgio poi segue Jenny nelle sue stanze.) |

(Jenny runs out covering her ears with her hands. George then follows Jenny into her rooms.) | |

| (La porta del fondo si apre ed entrano Skirner col servo. Il servo va sino alla porta della stanza di Chatterton, picchia, poi, non avendo risposta, apre l’uscio, guarda all’interno della stanza poi, volto a Skirner gli fa cenno di sedere. Skirner va a sedere presso al camino mentre il servo si allontana verso la porta del fondo lentamente. Chatterton appare. Il servo gli indica Skirner ed esce rinchiudendo la porta.) | (The door in the background opens and Skirner enters with a servant. The servant goes up to the door of Chatterton’s room, knocks, and receiving no reply, then opens the door, looks inside the room and turning to Skirner, motions to him to take a seat. Skirner sits down near the fire place while the servant slowly leaves in the direction of the door in the background. Chatterton appears. The servant points out Skirner to him and leaves closing the door.) | |

| Chatterton (atterrito) Skirner! qui!... Voi stesso! (si volge angosciosamente verso la porta ma il servo ha già chiuso) |

Chatterton (terrified) Skirner! You ... here ... in person! (he turned anxiously toward the door but the servant has already closed it) | |

| Skirner Buondì signore, perché vi turbate? Forse quest’oggi non m’aspettavate? |

Skirner Good day sir, why are you upset? Perhaps you didn’t expect me today? | |

| Chatterton Si, v’aspettavo! Uditemi. Per quanto io debbo un giorno solamente vi chieggo ancor d’attendere! Diman su me contate. |

Chatterton Yes, I was expecting you. Listen to me. For what I owe I ask you to wait only one more day! You can count on me tomorrow. | |

| Skirner Ma! che aspettate? Soccorsi certo no... Nulla vi resta! E giunto a tale può un’idea funesta balenare a lo spirito ... |

Skirner But what are you waiting for? Assistance, certainly not ... There’s nothing left for you! And having come to this it’s possible that some morbid idea might just come to mind ... | |

| Chatterton (con violenza) E vivadio! Se vo’ morire quest’è un diritto mio. |

Chatterton (with violence) And by God! If I want to die, it’s my right. | |

| Skirner Certo ... ma allor ... |

Skirner Certainly ... but then ... | |

| Chatterton Vi do gli scritti miei! |

Chatterton I shall give you my writings! | |

| Skirner E chi li acquista? No ... Ci perderei... |

Skirner And who would buy them? No... I would be the loser ... | |

| Chatterton Dunque voi rifiutate?! |

Chatterton You refuse then?! | |

| Skirner Garantitemi! |

Skirner Give me some assurance! | |

| Chatterton In qual modo? |

Chatterton In what way? | |

| Skirner (appressandosi e tirando un foglio dalla giubba e porgendolo a Chatterton) Ecco qui ... Solo firmatemi quest’atto che ho qui pronto. Così almeno, diman in ogni caso garantito son io. |

Skirner (drawing closer, taking a paper from his jacket and handing it to Chatterton) There then ... Just sign this document for me which I have prepared. At least this way, come tomorrow, in any case I’ll be secure. | |

| Chatterton (inorridito) Dio di pietà! Ed un uom fatto ad immagine tua mi parla così! |

Chatterton (horrified) God of mercy! A man made in your own image speaks to me thus! | |

| Skirner Non irritatevi. È sol per garanzia! |

Skirner Do not become annoyed. It is just a guarantee! | |

| Chatterton Taci! demonio! (firma l’atto) Questo carcame vuoi? Vampiro! Prendilo! |

Chatterton Be quiet! You devil! (Chatterton signs the document) You want this carcase? Vampire! Take it then! | |

| (gitta il foglio in faccia a Skirner che tosto lo raccoglie.) | (he throws the paper in Skirner’s face who quickly picks it up) | |

| Eccolo. Va! Di qui repente or togliti non insultare più la mia miseria! Va! Va! Va! (Skirner esce.) |

There it is. Get out! Now get yourself out of here immediately Insult my wretchedness no more! Out! Out! Out! (Skirner leaves.) | |

| È finita, mio Dio! (Giorgio compare sull’uscio) Ma questo è troppo! Orsù! (Chatterton tira della giubba una fiala) Meglio è pagarlo a l’istante, e cessar angosce ed onte! |

It is finished, my God! (George appears at the door) But this is too much! On with it! (Chatterton takes a phial out of his jacket) Better to pay him this very instant and end the anguish and dishonour! | |

| (Giorgio si avanza rapidamente non visto ed alla fine di questa battuta strappa la fiala a Chatterton e guarda il contenuto.) Ah! |

(George unseen moves quickly toward him, at the end of these words pulls the phial away from Chatterton and examines its contents) Ah! | |

| (Chatterton riprende vivamente la fiala a Giorgio e la nasconde nella giubba.) | (Chatterton quickly takes back the phial from George and hides it in his jacket) | |

| Giorgio (fingendo calma) Dell’oppio . Ve n’ha tanto da renderti esaltato dappria (ciò è ben gradevole ad un poeta). Invaso dal delirio tu sarai poscia, ed al fine un letargico sonno il tuo ciglio chiuderà in eterno. |

George (feigning calm) Some opium. There’s enough here to make you completely elated (that’s quite pleasant for a poet). You’ll then be overcome by delirium, and at the end a leaden sleep your eyes closing for ever. | |

| Chatterton E con esso m’avrò pace ed oblio Altro non spero! Altro non bramo! Addio! |

Chatterton And with it I shall have peace and oblivion I want nothing else! I desire nothing else! Goodbye! | |

| Giorgio Chatterton! resta. Iddio da l’alto soglio perdoni quel che sto per fare. Ascolta. Io, cristiano, a te di Dio nel nome svelo una cosa vera e per salvarti ricopro d’onta le mie bianche chiome! Tu non hai più diritto ad immolarti senza uccider colei che pei tuoi mali t’amò pietosa, eppur non sa d’amarti! |

George Chatterton! Wait. May God from his throne above forgive me for what I am about to do. Listen to me. As a Christian, I shall reveal to you in the name of God something which is true and to save you will cover my white hair with shame! You no longer have the right to sacrifice yourself without killing the one who has mercifully loved you for your sufferings but all the same knows not that she loves you! | |

| Chatterton Che parli mai! Che vuoi tu dire! (Giorgio cade in ginocchio piangendo) Levati! |

Chatterton Whatever do you mean! What are you trying to say! (George falls to his knees crying) Get up! | |

| Giorgio Grazia per lei! Grazia! Felice e pura un dì vivea! Se muori, se muori ella morrà. Salvala tu, la santa creatura! Come una figlia io l’amo ... abbi pietà! |

George Mercy for her. Mercy! She once lived happy and pure! If you die, if you die she will die. Save her, that sainted creature. I love her as a daughter ... have mercy! | |

| Chatterton Ma, il suo nome? |

Chatterton But, her name? | |

| Giorgio Or m’intendi. Inpenetrabile questo secreto a tutti dee restar. Se a lei lo sveli, come un miserabile con queste mani ti saprò sgozzar! |

George Now you understand me. This secret must remain impenetrable to all. If you reveal it to her, with these hands of mine I’ll throttle you like a wretch! | |

| Chatterton Jenny forse? |

Chatterton Can it be Jenny? | |

| Giorgio Ella stessa! |

George The very one! | |

| Chatterton Ed or che far deggio? Viver! morir! |

Chatterton And now what must I do? To live! To die! | |

| Giorgio Dei vivere, tacere E pregar Dio. |

George You must live, keep silent and pray to God. | |

| (Chatterton cade singhiozzando fra le braccia di Giorgio.) | (Chatterton falls sobbing into George’s arms.) | |