| CD 1 (69:39) | |||

ACT I | |||

| 1. | Vorspiel/Prelude/Prélude | 14:04 | |

| 2. | He! Ho! Waldhüter ihr | 8:27 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Erster und Zweiter Ritter, Erster und Zweiter Knappe, Kundry) | |||

| 3. | Recht so! - Habt Dank! - Ein wenig Rast | 5:59 | |

| (Amfortas, Zweiter Ritter, Gurnemanz) | |||

| 4. | Nicht Dank! - Haha! Was wird es helfen? | 4:35 | |

| (Kundry, Dritter und Vierter Knappe, Gurnemanz) | |||

| 5. | O wunden-wundervoller heiliger Speer! | 3:50 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Erster, Zweiter und Dritter Knappe) | |||

| 6. | Titurel, der fromme Held, der kannt'ihn wohl" | 6:42 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Knappen) | |||

| 7. | Weh! Weh!... Wer ist der Frevler? | 6:48 | |

| (Knappen, Ritter, Gurnemanz, Parsifal) | |||

| 8. | Nun sag! Nichts weißt du, was ich dich frage | 6:12 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Parsifal, Kundry) | |||

| 9. | Vom Bade kehrt der König heim | 2:03 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Parsifal) | |||

| 10. | Verwandlungsmusik/Transformation Music/Musique de Transformation | 3:29 | |

| 11. | Nun achte wohl und laß mich seh'n | 7:25 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Gralsritter, Jünglinge, Knaben) | |||

| CD 2 (79:24) | |||

| 1. | Mein Sohn Amfortas, bist du am Amt? | 10:01 | |

| (Titurel, Amfortas, Knaben, Jünglinge, Ritter) | |||

| 2. | Enthüllet den Gral! | 6:36 | |

| (Titurel, Stimmen, Knaben) | |||

| 3. | Wein und Brot des letzten Mahles | 10:44 | |

| (Knaben, Jünglinge, Ritter, Gurnemanz, Altstimme, Stimmen) | |||

ACT II | |||

| 4. | Vorspiel/Prelude/Prèlude Die Zeit ist da. - Schon lockt mein Zauberschloß den Toren | 5:36 | |

| (Klingsor) | |||

| 5. | Ach! - Ach! Tiefe Nacht! | 5:25 | |

| (Kundry, Klingsor) | |||

| 6. | Hier war das Tosen! Hier, hier! | 4:17 | |

| (Blumenmädchen I. und II. Gruppe, Parsifal, Chor I und II) | |||

| 7. | Komm, komm, holder Knabe! | 4:16 | |

| (Blumenmädchen I. und II. Gruppe, Parsifal, Chor I und II) | |||

| 8. | Parsifal! - Weile! | 2:46 | |

| (Kundry, Parsifal, Blumenmädchen I. und II. Gruppe, Chor I und II) | |||

| 9. | Dies alles hab'ich nun geträumt? | 3:18 | |

| (Parsifal, Kundry) | |||

| 10. | Ich sah das Kind an seiner Mutter Brust | 4:24 | |

| (Kundry) | |||

| 11. | Wehe! Wehe! Was tat ich? Wo war ich? | 4:49 | |

| (Parsifal, Kundry) | |||

| 12. | Amfortas! - Die Wunde! - Die Wunde! | 6:30 | |

| (Parsifal, Kundry) | |||

| 13. | Grausamer! Fühlst du im Herzen nur and'rer Schmerzen | 7:20 | |

| (Kundry, Parsifal) | |||

| 14. | Vergeh, unseliges Weib! | 3:17 | |

| (Parsifal, Kundry, Klingsor) | |||

| CD 3 (60:46) | |||

ACT III | |||

| 1. | Vorspiel/Prelude/Prélude | 4:55 | |

| 2. | Von dorther kam das Stöhnen | 5:54 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Kundry) | |||

| 3. | Heil dir, mein Gast! | 7:04 | |

| (Gurnemanz) | |||

| 4. | Heil mir, daß ich dich wiederfinde! | 3:37 | |

| (Parsifal, Gurnemanz) | |||

| 5. | Nicht so! - Die heil'ge Quelle selbst erquicke unsres Pilgers Bad | 3:55 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Parsifal) | |||

| 6. | Gesegnet sei, du Reiner, durch das Reine!... Wie dünkt mich doch die Aue heut so schön! | 7:41 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Parsifal) | |||

| 7. | Du siehst, das ist nicht so | 5:58 | |

| (Gurnemanz, Parsifal) | |||

| 8. | Mittag. - Die Stund' ist da | 4:34 | |

| (Gurnemanz) | |||

| 9. | Geleiten wir im bergenden Schrein den Gral zum heiligen Amte | 3:42 | |

| (Ritter) | |||

| 10. | Ja, Wehe! Wehe! Weh'über mich! | 6:14 | |

| (Amfortas, Ritter) | |||

| 11. | Nur eine Waffe taugt | 3:25 | |

| (Parsifal) | |||

| 12. | Höchsten heiles Wunder! | 3:40 | |

| (Knaben, Jünglinge, Ritter) | |||

Producer: Igor Kipnis

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston and Jon Samuels

Photographs: Charles Mintzer

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank Rudi Van den Bulck, Fabian Piscitelli, and Gary Thalheimer.

Marston would also like to thank César Arturo Dillon whose research, photographs, and biographical information were invaluable to the production of this CD set.

This CD set is dedicated to the memory of Igor Kipnis

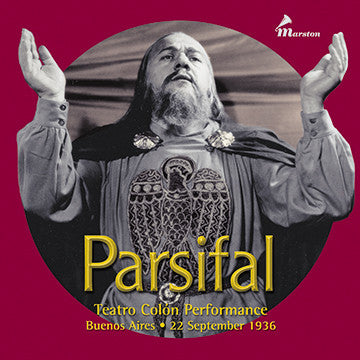

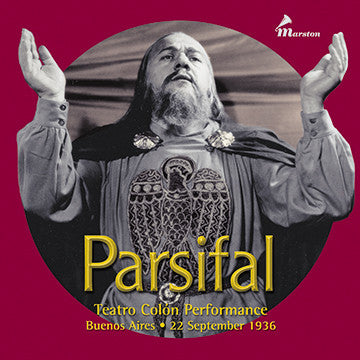

Richard Wagner (1813-1883)Parsifal22 September 1936 | |

| Opera in three acts | |

| Libretto by Richard Wagner | |

| Amfortas | Martial Singher |

| Titurel | Fred Destal |

| Gurnemanz | Alexander Kipnis |

| Klingsor | Fritz Krenn1 |

| Parsifal | René Maison |

| Kundry | Marjorie Lawrence |

| Gralsritter | Hans Fleischer, Jorge Andronoff |

| Knaben | Lucy Ritter, Irra Petina, Hans Fleischer, Luis Santoro |

| Blumenmädchen | Editha Fleischer, Lucy Ritter, Maria Malberti, |

| Irra Petina, Emma Brizzio, Yolanda di Sabato | |

| Fritz Busch, conductor Teatro Colón Orchestra and Chorus, Buenos Aires Rafael Terragnolo, chorus master Hans Busch, production2 Hector Basaldúa, sets | |

| 1 Fritz Krenn replaced Fred Destal in the role of Klingsor for this performance 2 The original 1933 production was by Carl Ebert, revived by Hans Busch | |

Synopsis

Act I:

In a forest near the castle of Monsalvat in the Spanish Pyrenees, Gurnemanz, Knight of the Holy Grail, rises with his two young esquires from sleep. Two other knights arrive to prepare a morning bath for the ailing monarch Amfortas, who has an incurable wound. They are interrupted by Kundry, an ageless woman of many guises, who rushes in wildly with balsam for Amfortas. The king and his suite now enter, accept the gift and proceed to the nearby lake (“Recht so! Habt Dank! Ein wenig Rast”). As Gurnemanz bewails Amfortas’ wound, his companions ask him to tell about Klingsor, the sorcerer who is trying to destroy them. Gurnemanz explains that Klingsor once tried to join the knightly brotherhood. Denied because of his lustful thoughts, he tried to gain acceptance by castrating himself and was rejected. Now an implacable foe, Klingsor entrapped Amfortas with a beautiful woman: while the king was lying in her arms, Klingsor snatched the Holy Spear (which had pierced Christ’s side) and stabbed Amfortas (“Oh, wunden-wundervoller heiliger Speer!”). A prophecy has since revealed that the wound can be healed only by an innocent youth enlightened through compassion (“Durch Mitleid wissend”). Suddenly a swan falls to the ground, struck by an arrow. The knights drag in a youth, Parsifal, whom Gurnemanz gently rebukes for his foolhardy act. The boy flings away his bow and arrows in shame but cannot explain his conduct or even state his name. Kundry tells the youth’s history: his father, Gamuret, died in battle; his mother, Herzeleide, reared the boy in the forest, but now she too is dead (“Den Vaterlosen gebar die Mutter”). Enraged, Parsifal springs at Kundry, but is restrained by Gurnemanz. Kundry, overcome with weariness, but unable to resist, disappears into the woods to sleep. The knights carry Amfortas’ litter back from the lake. Gurnemanz leads Parsifal to the castle of the Grail, wondering if he may be the prophecy’s fulfillment (Transformation Scene).

In the lofty Hall of the Grail, Amfortas and his knights prepare to celebrate the Last Supper (“Zum letzten Liebesmahle”). The voice of the king’s father, the aged Titurel, bids him uncover the Holy Grail and proceed but Amfortas hesitates. His anguish rises in the presence of the blood of Christ (“Nein! Lasst ihn unenthüllt!”). At length Titurel orders the esquires to uncover the chalice, which casts its glow about the hall. As the bread and wine are offered, an invisible choir is heard from above (“Wein und Brot”). Parsifal watches with astonishment, but understands nothing. As Amfortas cries out in pain Parsifal clutches his heart. Though Gurnemanz angrily drives the uncomprehending boy away (“Was stehst du noch da?”), a voice reiterates the prophecy.

Act II:

In his dark tower, Klingsor summons his thrall Kundry to seduce Parsifal (“Herauf! Herauf! Zu mir!”); having secured the Spear through Amfortas’ weakness, he now seeks to inherit the Grail by destroying Parsifal, whom he knows is the order’s salvation. Kundry, hoping for redemption, protests in vain.

In Klingsor’s magic garden Flower Maidens beg for Parsifal’s embrace (“Komm’! Komm’! Holder Knabe!”), but he resists them. With Kundry’s arrival they slowly withdraw. Kundry, transformed into a beautiful young woman, begins her seduction by revealing tender memories of his mother and childhood. (“Ich sah’ das Kind”). When she breaks down his resistance, she offers a passionate kiss. At this moment he understands both the mystery of Amfortas’ wound and his own mission (“Amfortas! – die Wunde!”). Kundry now tries to lure him through pity for the weary life she has been forced to lead ever since she laughed at Christ on the Cross (“Seit Ewigkeiten harre ich deiner”), but she is rejected. She curses Parsifal to wander hopelessly in search of Monsalvat and calls on Klingsor for help. Confident that he will triumph over Parsifal, the magician hurls the Holy Spear which Parsifal miraculously catches. With the Holy Spear Parsifal makes the sign of the cross, and causes Klingsor’s realm to vanish (“Mit diesem Zeichen bann’ ich deinen Zauber”).

Act III:

Gurnemanz, now a hermit and grown old, finds the penitent Kundry exhausted in a thicket near his little hut. As he revives her, a strange knight in full armor approaches. Gurnemanz recognizes Parsifal and the Holy Spear, whereupon the knight describes his years of trying to find his way back to Amfortas and the Grail (“Der Irrnis und der Leiden Pfade”). Gurnemanz removes Parsifal’s armor; Kundry washes his feet, drying them with her hair. Gurnemanz blesses Parsifal and pronounces him king (“So ward es uns verhiessen, so segne ich dein Haupt”). As his first task Parsifal baptizes Kundry, then rejoices in the beauty of the meadow. The hermit replies that this is the spell of Good Friday (“Das ist Karfreitagszauber, Herr!”) The tolling of distant bells announces the funeral of Titurel. Solemnly they walk to the castle (Transformation Scene). But a new leader, Parsifal, touches Amfortas’ side with the Spear and heals the wound. Raising the sacred chalice aloft, he accepts the homage of the knights as their new king and blesses all (“Nur eine Waffe taugt”). Kundry has been redeemed and the brotherhood of the Grail has been saved.

--Courtesy of Opera News

A Personal Recollection

By Hans Busch

On the evening of 7 March 1933, the Dresden State Opera was scheduled to give Rigoletto under the baton of my father, Fritz Busch, the company’s general music director. The house was sold out that night, any remaining tickets having been bought up not by Verdi enthusiasts but by members of Hitler’s S.A. As my father made his way to the podium, the Brownshirts in the audience began a chorus of boos so deafening as to prevent the performance from even starting. My father laid down his baton and left the auditorium before any S.A.-planned riot could begin.

Long before the Holocaust, my father, with rare common sense, had seen, as it were, the swastika on the wall. For him the Nazis were nothing more than thugs, and outspoken as he always was, he made no secret of his contempt for the movement and its hateful ideology. So by January 1933, when Hitler came to power, Fritz Busch’s opposition to the Nazis was well known.

Following that ill-fated Rigoletto, my father resigned his position as music director at Dresden. Shortly thereafter he left Germany in protest, returning only in 1951, the year of his death.

The next time Fritz Busch raised his baton was at the famed Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. There, in summer, 1933, he made his long-awaited South American debut conducting a series of memorable Wagner performances in the Colón’s German temporada (season), held each winter (our summer). Buenos Aires hailed my father as the greatest Wagner conductor it had ever experienced. Pleased by the Colón’s superb orchestra, chorus, and soloists, Fritz Busch happily returned for the German temporadas of 1934, 1935, and 1936, alternating between Buenos Aires, the Glyndebourne Mozart Festivals, and the Danish State Radio Symphony. By the time war broke out, he considered Buenos Aires his home.

The temporada of 1936 included revivals of productions of Parsifal and Der Rosenkavalier, both first seen in that debut season of 1933. Earlier I had had the opportunity to serve as assistant to the stage director of those productions, Carl Ebert; now, in 1936, I was to direct myself. Hard work and youthful enthusiasm compensated for whatever talent or experience I was lacking at that time. The distinguished cast, including Alexander Kipnis, Marjorie Lawrence, and my future brother-in-law Martial Singher, proved unfailingly helpful, kindly accepting my direction and lending all their moral support.

Marjorie Lawrence in particular took a kindly interest in her twenty-two-year-old director. At one point during rehearsals, Miss Lawrence, as Kundry, asked whether in Act II she should kiss Parsifal a second time. She was totally unfazed by the reply I hastily blurted out, resorting to the multi-lingual jibberish favored by the Colón’s stagehands of Italian descent: “Ne kiss pas otra volta.”

Many years later, when Miss Lawrence, now confined to a wheelchair, was in Bloomington to judge Metropolitan Opera auditions, she shared a good laugh with me as I quoted to her that rather bizarre direction of mine from 1936.

Bloomington, August, 1966

(Hans Busch was professor emeritus at the School of Music, Indiana University in Bloomington, and was the author of several books on the operas of Giuseppe Verdi. He died in September, 1966.)

Parsifal and the Radio Era in Buenos Aires

By César A. Dillon

Felix Weingartner conducted a very special Parsifal performance at the Teatro Coliseo in Buenos Aires on 27 August 1920. This event was important not just because it was opening night but because four friends (Enrique Telémaco Susini, a doctor, and three medical students, Luis Romero Carranza, César Guerrico, and Miguel Mujica) installed a transmitter with an antenna on the roof of the theater and broadcast the entire performance. This is acknowledged as the beginning of the radio era in Buenos Aires, and many years later, 27 August was named “Dia de la Radiodifusión” (Radio Day) in Argentina. Supposedly some fifty people could hear the broadcast in the city, but there was news that it was heard by a radio operator in a ship harbored in Santos (Brazil). There was even a newspaper review giving details of the broadcast.

This is believed to be the first complete opera broadcast in the world, and more important, the whole season was broadcast (Aida, Salome, Francesca da Rimini, Pelléas et Mélisande, Der Rosenkavalier, Mefistofele, Il Barbiere di Siviglia, La Bohème, Iris, Rigoletto, Manon, Le Jongleur de Notre Dame, Tosca, Lohengrin, Die Walküre, Cavalleria Rusticana, La Gioconda, Thaïs, Andrea Chénier, and Carmen.) Some of the singers of that season were Bernardo de Muro, Elvira Casazza, Beniamino Gigli, Luigi Rossi Morelli, Geneviève Vix, Armand Crabbé, Lina Pasini-Vitale, Gilda dalla Rizza, Giacomo Lauri Volpi, Giulio Cirino, and Angeles Ottein. (During this season Susini and his friends also broadcast the complete subscription concert series under Weingartner from the same stage.)

With the success and interest from this first season, Susini and his friends received permission from theater managers Walter Mocchi and Faustino da Rosa to record the opera and operetta performances from several stages of the city, including the Colón. Susini broadcast numerous performances for several years hence.

The Cast

Martial Singher (Amfortas)

14 August 1904 Oloron-Ste Marie, France; 9 March 1990 Santa Barbara, California

Singher studied singing at the Paris Conservatoire with bass André Gresse. He performed as Orestes to Germaine Lubin’s Iphigénie on 20 November 1930 at the Stadsschouwburg in Amsterdam in a guest appearance of the Paris Opéra’s Iphigénie en Tauride. His official Paris Opéra debut was as Athanaël in Thaïs at the Palais Garnier on 21 December 1930. His big break occurred when he replaced Vanni Marcoux in 1931 as Iago in Otello, which led to an Opéra contract as a leading baritone. In 1932 he created the song cycle Don Quichotte à Dulcinée, which had been dedicated to him by the composer, Maurice Ravel. After 1937 he was a respected member of the Opéra-Comique. Singher made guest appearances at the Teatro Colón in 1936 and 1937. He fled occupied France for the United States on a visitor’s visa en route to South America in 1940 and in the same year he married Margareta (Eta) Rut Busch, the daughter of the conductor Fritz Busch. He returned to the Colón in 1942 and 1943, and then sang 162 performances with the Metropolitan Opera. He taught at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, and Mannes College of Music in New York. Singher succeeded Lotte Lehmann as the director of voice and opera at Santa Barbara’s Music Academy of the West from 1962 to 1981. Martial Singher’s superb baritone voice was elegant and well-schooled.

Fred Destal (Titurel)

1905; 1978 New York City, New York

Destal began his career as a choirboy in Liegnitz and trained at the Stadttheater in Plauen from 1928–1930. In 1930 he moved to the Deutsches Theater in Brünn, then joined the Deutsches Opernhaus (later the Städtisches Oper) in Berlin the following year. In 1933 he left Germany for the Zurich Opera. He sang at the Vienna State Opera from 1936–1938, and emigrated to the United States in 1938. He made many guest appearances in Europe and frequently performed at the Colón: 1936, Der fliegende Holländer, Lohengrin, Die Fledermaus, and Parsifal; 1940, Parsifal, Der fliegende Holländer, Der Zigeunerbaron, and Die Walküre; 1941, Die Meistersinger, Die Zauberflöte, Die Fledermaus, and Lohengrin; 1947, Das Rheingold, Siegfried, Götterdämmerung, and Der Rosenkavalier.

Alexander Kipnis (Gurnemanz)

13 February 1891 Zhitomir, Ukraine; 14 May 1978 Westport, Connecticut

Kipnis entered the Warsaw Conservatory at age nineteen. In 1912 he traveled to Berlin, where he began studying voice with Ernst Grenzebach, who was also the teacher of Lauritz Melchior, Max Lorenz, and Meta Seinemeyer. While in Berlin, Kipnis, a Russian, was interned. Freed in 1915, he made his stage debut in Hamburg, singing three Strauss songs as a “guest” in the second act party scene of Die Fledermaus. In 1922 Kipnis joined the Deutsches Opernhaus in Berlin; from 1923–1932 he was on the roster of the Chicago Civic Opera; in 1927 he sang in Parsifal under Karl Muck at the Bayreuth Festival; and in 1938 he settled permanently in the United States. By the time of his Metropolitan Opera debut in 1940 as Gurnemanz, he had sung at virtually every major opera house and festival, including the Colón, where he appeared in 1926, 1928, 1931, 1934–1936, and 1941. According to his son, the late keyboardist Igor Kipnis, Alexander Kipnis sang 108 roles from 1915–1951 and performed in opera and oratorio over 1600 times. Following his retirement from the Metropolitan in 1946 (his last concert appearances were in 1951), he began teaching, first at the New York College of Music and then in 1966 at the Juilliard School. Alexander Kipnis’s voice was large and beautiful, admired particularly in the Russian repertory, and his acting talent, versatility, and skill as a lieder singer are also well-known.

Fritz Krenn (Klingsor)

11 December 1887 Vienna; 17 July 1963 Vienna

Krenn studied at the Wiener Musikakadmie and made his stage debut in 1917. From the mid-1920s he sang at several of the Berlin opera houses and took part in the world premiere of Hindemith’s Neues vom Tage at the Kroll-Oper under Klemperer (1929). At the Teatro Colón he made his debut during the 1931 season as Jokanaan in Salome, and also took part in Die Fledermaus, Tristan und Isolde, Das Rheingold, and Götterdämmerung. Krenn appeared at the Salzburg Festival (1935, 1938, 1939) as Pizarro in Fidelio and Baron Ochs in Der Rosenkavalier, his most famous role, which he sang nearly 400 times. Krenn returned to the Colón for the 1936 season, singing in Lohengrin, Parsifal, Die Fledermaus, and Der Rosenkavalier. In 1939 at the San Francisco Opera, he sang Fidelio with Kirsten Flagstad, Alexander Kipnis, and Marjorie Lawrence, and Die Walküre with Flagstad, Lawrence, Kipnis, and Lauritz Melchior. At the Vienna Opera after the war he sang thirty-nine performances as Ochs in Der Rosenkavalier. There he also sang Cavalleria rusticana, Fidelio (Pizarro, Don Fernando), Der Zigeunerbaron (Homonay, Zsupan), Bartered Bride (Kezal), Die Meistersinger (Kothner), Don Giovanni (Leporello), Der Freischütz (Ottokar), Arabella (Waldner), and many other roles. During these years he became a member of the Volksoper, singing several hundred operetta performances. He also sang at the Bayreuth Festival, La Scala, and Covent Garden. Krenn made a late debut (he was sixty-three years old) at the Metropolitan in New York during the 1950 season, singing seven performances as Baron Ochs, and lived out his last years in Vienna with his wife Luise Kornfeld.

René Maison (Parsifal)

24 November 1895 Frameries, Belgium; 11 July 1962 Mont-Dore, France

Maison studied singing in Paris and Brussels and made his debut in Geneva as Rodolfo in La Bohème (1920). After appearances in the French and Belgian provinces, he was engaged at the Opéra-Comique in 1927, making his debut there as Dimitri in the first performance in that theater of Alfano’s Résurrection, opposite Mary Garden. He was engaged at the Chicago Opera (1928–1931) and made guest appearances at Covent Garden, the Brussels Opera, and in San Francisco. He recorded for Odeon in 1930. He was a member of the Metropolitan Opera (1935–1943) where he made his debut as Walther in Die Meistersinger, and in 1934, 1935, 1936, 1940, and 1941 he took part in twenty productions at the Colón in Buenos Aires. After his retirement from stage he taught singing in Mexico City, New York (Juilliard), and in Boston. René Maison had a beautifully expressive voice that was particularly brilliant in French repertoire as well as in Wagnerian roles.

Marjorie Lawrence (Kundry)

17 February 1909 Melbourne; 13 January 1979 Little Rock, Arkansas

Lawrence studied singing in Melbourne and later in Paris with Cécile Gilly. She made her debut at Monte Carlo in 1932 as Elisabeth in Tannhäuser, and from 1933 to 1938 she sang regularly at the Paris Opéra. She made her U.S. debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in late 1935 as Brünnhilde in Die Walküre, and through 1941 she was engaged in eighty-six performances there. Her time at the Colón was far less prolific; she sang in four productions in 1936 and three productions in 1940. As the title of her autobiography Interrupted Melody suggests, her singing career was tragically altered when she was paralyzed in both her legs by polio in 1941 when she appeared as a guest in Mexico City. Her career was only briefly interrupted, as she performed in specially staged productions such as Venus in Tannhäuser and Amneris in Aida at the Metropolitan Opera. She also performed title roles in concert presentations, however her career was greatly truncated. In later years Marjorie Lawrence devoted herself to teaching in the U.S. From 1956 to 1960 she taught at Tulane University in New Orleans, later at the University of Southern Illinois, and she conducted summer sessions at her ranch in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Marjorie Lawrence’s large and opulent voice was especially well-suited to the big Wagnerian roles.

Editha Fleischer (Blumenmädchen)

5 April 1895 Falkenstein (Oberpfalz); unknown

Fleischer studied with Lilli Lehmann and made her debut in 1918 in Berlin. She sang Susanna in Le nozze di Figaro and Zerlina in Don Giovanni at the Salzburg Festival in 1922. She toured North America between 1922–1924 with the German Opera Company and then remained in the United States to join the William Wade Hinshaw Opera Company. In 1926 she joined the Metropolitan Opera in the role of First Lady in Die Zauberflöte and sang 400 performances with the Metropolitan Opera between 1926–1936.

At the Teatro Colón she sang in five seasons, 1933–1937: 1933, Die Meistersinger (Eva), Der Rosenkavalier (Sophie), and Fidelio (Marcellina); 1934, Falstaff (Alice), La fiamma (Monica), Cosi fan tutte (Despina), Arabella (Zdenka), and Bartered Bride (Marenka); 1935, Falstaff (Alice), Schwanda (Dorota), and Don Giovanni (Zerlina); 1936, Werther (Sophie), Le nozze di Figaro (Susanna), and Die Fledermaus (Adele); 1937, Falstaff (Alice), and Fidelio (Marcellina). Fleischer was married to conductor Erich Engel, who was Busch and Kleiber’s assistant at the Colón for nearly fifteen years, and she was the sister of Hans Fleischer, who also sang in 1936 Parsifal performance. During the 1940s she taught singing at the Colón and later taught at the Conservatory of the city of Vienna. Editha Fleisher was a highly regarded concert soprano.

The Conductor

Fritz Busch

13 March 1890 Siegen, Westphalia; 14 September 1951 London

German musical life was influenced by many outstanding conductors during the first half of the twentieth century. Fritz Busch was one of the greatest among them. The son of a unique man —a carpenter, violin-maker, musical instrument dealer, and a self-taught amateur musician —Fritz Busch was born in Siegen, Westphalia, on 13 March 1890. Two of his brothers also achieved world renown as musicians: Adolf, violinist and composer, and cellist Hermann. Already a proficient pianist as a young child, Fritz Busch attended the Cologne Conservatory from 1906 to 1909, studying piano with Karl Boettcher and conducting with Fritz Steinbach. Immediately after graduating he conducted at the Deutsches Theater in Riga. The following year he was conductor of the spa orchestra in Bad Pyrmont, and in the winter months director of the Musikverein in Gotha. In 1911 he married Grete Boettcher, the niece of his piano teacher, and in 1912 he was appointed Music Director of the city of Aachen. His work in Aachen was interrupted by the First World War, in which he served as a soldier. From 1918 to 1922 he conducted in Stuttgart, before being called to the Sächsische Staatsoper in Dresden. Until 1933 Fritz Busch led the Sächsische Staatskapelle in over 1000 opera and concert performances. In addition to championing the then practically unknown works of Giuseppe Verdi, he was also an open-minded supporter of the musical avant-garde of the 1920s. Richard Strauss was so delighted with the world premieres of his operas Intermezzo and Die Aegyptische Helena that he dedicated his Arabella to Fritz Busch and Dresden’s Intendant Dr. Alfred Reucker. In 1924 the Bayreuth Festival reopened after a ten-year hiatus, with Fritz Busch conducting Die Meistersinger. He was also a frequent guest conductor in New York, Berlin, Leipzig, Salzburg, and other European music centers. Because Fritz Busch refused to collaborate with the National Socialists, he was driven out of the Staatsoper in Dresden in a dramatic episode before a Rigoletto performance on 7 March 1933. He left Germany and found new spheres of activity in Buenos Aires, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and New York. With his friend, the stage director Carl Ebert, he founded the Glyndebourne Festival, which rapidly achieved world fame. In the fall of 1950 Fritz Busch conducted at the Vienna State Opera, and was asked to become its musical director. Only in 1951 did he return to Germany. He was so enthusiastically received in Cologne and Hamburg, that he believed it was possible to build new bridges to a new Germany. But unfortunately this was never to happen. After a successful season in Glyndebourne and a guest appearance in Edinburgh, Fritz Busch died in London on 14 September 1951.

Lia Frey-Rabine, 1996

The 1936 Teatro Colón performance of Parsifal is undoubtedly the earliest complete recording of the opera. About twenty years ago, I first heard of this recording’s existence and eagerly awaited its eventual release on LP or later, on CD. As years passed, I heard nothing more about it and I assumed that either the recording had been lost or that it was so sonically inferior as to prevent its ever being released. Several years ago, however, I was given access to the original source discs and I am pleased to present here, for the first time, this fascinating performance of Wagner’s last music drama.

During the Colón’s 1936–1937 season, four entire operas were recorded—Parsifal, Lohengrin, Der fliegende Holländer, and Der Rosenkavalier. No one seems to be certain as to exactly why the recordings were made and why other operas in that season were not transcribed. What is certain is that these four operas are the earliest recordings emanating from the stage of the great Teatro Colón.

Turning our attention to Parsifal, I thought it advisable to explain how the recording was made and discuss some of its technical flaws. The performance was recorded on sixteen- inch, aluminum-based, lacquer-coated discs. Using two turntables running at approximately 32.8 rpm, the recording covers sixteen sides. I have been told that the recording equipment was located in the basement of the Colón and that three microphones were used, one above the orchestra, a second above the front of the stage, and a third over the rear of the stage. Unfortunately, the operator of this equipment did not know how to adjust the three microphones properly to achieve a comfortable balance between singers and orchestra. Throughout the performance, the engineer constantly changed the sound level and switched microphones on and off seemingly for no reason at all. The singers are, therefore, not always as audible as one would like them to be. Another flaw in the recording occurs during the change from one side to another. At these points, there is, for some reason, about a quarter second of missing music which makes it impossible to join the sides seamlessly. Finally, I should mention the presence of some radio interference during Act Two where one can hear two short bursts of dance band music. As occasionally happens, this was probably picked up by the cutting apparatus.

In remastering this recording, my first task was to eliminate as much surface noise as possible without compromising the sound on the original discs. This was accomplished by carefully cleaning the discs and by wetting them while they were being played. I also found that using several different sizes of styli on different portions of the discs produced an enormous sonic improvement. I next attempted to remove many hundreds of clicks and pops which afflict this recording. CEDAR technology proved to be a tremendous help in this process but many pops still had to be removed manually using Sonic Solutions software. Some very large clicks were impossible to remove without affecting the integrity of the music. Finally, I attacked the problem of the erratic sound level changes during the performance. With careful editing, I was able to improve some of the most egregious examples. In many cases, however, the changes in balance were impossible to correct effectively. Despite these problems, the sound of the recording is quite good for the time and one does truly have the feeling of actually being in a seat at the Colón. Over the next two years, I plan to release the other three operas from that season beginning with a splendid performance of Der Rosenkavalier featuring Tiana Lemnitz, Editha Fleischer, Germaine Hoerner, and Alexander Kipnis.