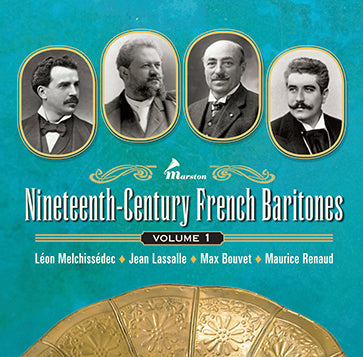

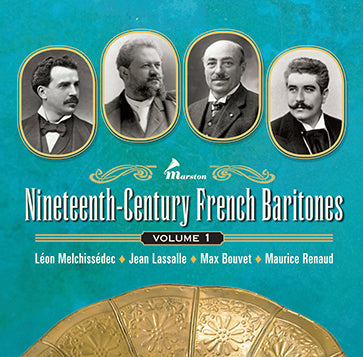

Léon Melchissédec, 1843-1925 was an invaluable member of three Paris companies: the Opéra-Comique, the Théâtre Lyrique, and the Paris Opéra. He is the earliest born French baritone to make authenticated commercial recordings beginning in 1899. Included in this compilation is his first recording, a seven-inch Berliner label disc, a group of Pathé cylinders, three discs for Zonophone, and six-disc sides for the APGA label recorded in 1907-1908.

Jean Lassalle, 1847-1909, was one of the greatest luminaries of the Paris Opéra, was a frequent guest in London, and an honored member of the Metropolitan Opera. Although his recordings were made when he was in his late fifties there is still much to be enjoyed in the way of style and technique. His first recordings were Pathé cylinders dating from 1902, some of which are released here on CD for the first time. Also included are his seven-disc sides for Odeon and two-Pantophone sides made in 1904 and 1905.

Max Bouvet, 1854–1943, began his career in café-concert and operetta. He joined the Opéra-Comique in 1884 remaining there until 1900. He also sang at Covent Garden and enjoyed a long stint at Monte-Carlo. He recorded exclusively for Pathé: cylinders in 1903 and 1904, and discs in 1907.

Maurice Renaud, 1861–1933, was the most internationally acclaimed of our four baritones. His thirty-seven-year career has been well-documented and we have already issued his complete Gramophone Company recordings on Marston 52005. We have now chosen this set for inclusion of Renaud’s extant Pathé recordings.

This compilation is one of our most important releases not only for the rarity of the recordings but more importantly for the understanding of French style displayed by these singers. We hope to follow this with a second baritone volume devoted to Lucien Fugère, 1848-1936, and Gabriel Soulacroix, 1854-1905.

CD 1 (63:50) | ||

Léon Melchissédec | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, JULY 1899 | ||

| 1. | LE CAÏD: Je comprends que la belle … Enfant chéri des dames (Thomas) | 2:34 |

| 3069 (Berliner 32639) | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDERS, PARIS, CA. NOVEMBER 1899 | ||

| 2. | LE CAÏD: Je comprends que la belle … Enfant chéri des dames (Thomas) | 2:42 |

| 3694 (brown-wax Standard cylinder “Série artistique” 3694) | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDERS, PARIS, 1902 | ||

| 3. | FAUST: Vous qui faites l’endormie (Gounod) | 2:21 |

| 3680 (early molded Standard cylinder 3680) | ||

| 4. | FAUST: Vous qui faites l’endormie (Gounod) | 2:18 |

| 3680 [alternative take] (early molded Standard cylinder 3680) | ||

| 5. | FAUST: Écoute-moi bien, Marguerite (Gounod) | 2:08 |

| 3681 (molded Standard cylinder 3681 [1254]) | ||

| 6. | FAUST: Écoute-moi bien, Marguerite (Gounod) | 2:18 |

| 3681 [alternative take] (molded Standard cylinder 3681) | ||

| 7. | LES DRAGONS DE VILLARS: Quand le dragon a bien trotté (Maillart) | 2:17 |

| 3698 (molded Standard cylinder 3698) | ||

| 8. | LES DRAGONS DE VILLARS: Le sage qui s’éveille (Maillart) | 2:18 |

| 3699 (molded Standard cylinder 3699) | ||

| 9. | La Marseillaise (Rouget de Lisle) | 2:22 |

| 3705 (molded Standard cylinder 3705) | ||

INTERNATIONAL ZONOPHONE, PARIS, CA. NOVEMBER 1902 | ||

| 10. | GUILLAUME TELL: Sois immobile (Rossini) | 2:56 |

| [Leçon de chant (singing lesson, where Melchissédec sings the aria interjecting his comments between phrases)] *see transcription and translation on p. 52 | ||

| X-2109 (10-inch disc X-2109) | ||

| 11. | GUILLAUME TELL: Sois immobile (Rossini) | 2:16 |

| [Leçon de chant (singing lesson, where Melchissédec sings the aria interjecting his comments between phrases)] | ||

| 11853 (7-inch disc 11853) | ||

| 12. | La Marseillaise (Rouget de Lisle) | 2:49 |

| X-2060-2 (10-inch disc X-2060) | ||

ASSOCIATION PHONIQUE DES GRANDS ARTISTES (APGA), PARIS, CA. MARCH 1907 | ||

| 13. | L’AFRICAINE: Fille des rois (Meyerbeer) | 2:18 |

| 1624-1 (1624) | ||

| 14. | L’AFRICAINE: Adamastor, roi des vagues profondes (Meyerbeer) | 3:13 |

| 1625-1 (1625) | ||

| 15. | UN BALLO IN MASCHERA: Eri tu che macchiavi (Et c’est toi qui déchires) (Verdi) | 3:12 |

| 1626-1 (1626) | ||

| 16. | RIGOLETTO: Miei signori (Ô mes maîtres) (Verdi) | 2:11 |

| 1627-1 (1627) | ||

ASSOCIATION PHONIQUE DES GRANDS ARTISTES (APGA), PARIS, CA. NOVEMBER 1908 | ||

| 17. | DON GIOVANNI: Deh vieni alla finestra (Je suis sous ta fenêtre) (Mozart) | 1:55 |

| A 150 (1990) | ||

| 18. | ROMÉO ET JULIETTE: Soyez les bienvenus, amis, dans ma maison … Allons, jeunes gens! (Gounod) | 2:51 |

| A 151 (1991) | ||

Jean Lassalle | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDERS (SOME LATER REISSUED AS DISCS), PARIS, CA. DECEMBER 1902 | ||

| 19. | ASCANIO: Enfants, je ne vous en veux pas (Saint-Saëns) | 2:21 |

| 2866 (molded Standard cylinder 2866 [4606]) | ||

| 20. | Le sais-tu bien? (Pierné) | 2:23 |

| 2868 (early molded Standard cylinder 2868) | ||

| 21. | Zhelanye (Le rêve du prisonnier), Op. 8, No. 5 (Rubinstein) | 2:23 |

| 2869 (molded Standard cylinder 2869 [3255]) | ||

| 22. | LE ROI DE LAHORE: Promesse de mon avenir (Massenet) | 2:27 |

| 2871 (molded Standard cylinder 2871) | ||

| 23. | LE ROI DE LAHORE: Promesse de mon avenir (Massenet) | 2:26 |

| 2871 [alternative take] (24cm center-start disc 2871 [5072 C]) | ||

| 24. | TANNHÄUSER: O du mein holder Abendstern (Ô douce étoile, feu du soir) (Wagner) | 2:18 |

| 2874 (molded Standard cylinder 2874 [10343]) | ||

| 25. | LA DAMNATION DE FAUST: Voici des roses (Berlioz) | 2:22 |

| 2876 (molded Inter cylinder 2876 [3639]) | ||

| 26. | In der Fremde (Au loin), No. 1 from LIEDERKREIS, Op. 39 (Schumann) | 2:12 |

| 2879 (molded Standard cylinder 2879 [2357]) | ||

| All tracks are with piano except tracks 13-16 which are with orchestra, and track 2 which is sung with no accompaniment | ||

| All tracks sung in French | ||

CD 2 (56:32) | ||

Jean Lassalle | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDERS (SOME LATER REISSUED AS DISCS), PARIS, CA. DECEMBER 1902 | ||

(continued) | ||

| 1. | PAUL ET VIRGINIE: L’oiseau s’envole (Massé) | 2:24 |

| 2884 (molded Standard cylinder 2884) | ||

| 2. | POÈME D’AMOUR: Ouvre tes yeux bleus (Massenet) | 2:21 |

| 2885 (molded Standard cylinder 2885 [2710]) | ||

| 3. | POÈME D’AMOUR: Ouvre tes yeux bleus (Massenet) | 2:34 |

| 2885 [alternative take] (early molded cylinder 2885) | ||

| 4. | DON GIOVANNI: Deh vieni alla finestra (Je suis sous ta fenêtre) (Mozart) | 2:18 |

| transposed down a semi-tone to D-flat | ||

| 2892 (molded Standard cylinder 2892) | ||

| 5. | DON GIOVANNI: Deh vieni alla finestra (Je suis sous ta fenêtre) (Mozart) | 2:24 |

| transposed down a semi-tone to D-flat | ||

| 2892 [alternative take] (24cm center-start disc 2892 [6104 C]) | ||

| 6. | Chant provençal (Massenet) | 2:14 |

| 2985 (molded Inter cylinder 2985 [27131]) | ||

| 7. | Plaisir d’amour (Martini) | 2:26 |

| 2986 (molded Standard cylinder 2986 [1197]) | ||

| 8. | Amour d’automne (Chaminade) | 2:23 |

| 2987 (molded Standard cylinder 2987 [2858]) | ||

| 9. | Si tu veux, mignonne (Massenet) | 2:27 |

| 2988 (early molded Standard cylinder 2988) | ||

| 10. | Les sapins (Dupont) | 2:30 |

| 2990 (molded Standard cylinder 2990 [1523]) | ||

PATHÉ CÉLESTE CYLINDERS (LATER REISSUED AS DISCS), PARIS, 1903 | ||

| 11. | Pensée d’automne (Massenet) | 4:36 |

| 3905 (29cm center-start discs 3905-1 [18572 BC] and 3905-2 [18571 BC]) | ||

ODÉON DISCS, PARIS, OCTOBER 1904 | ||

| 12. | Chant provençal (Massenet) | 3:14 |

| xP 1043 (33914) | ||

| 13. | Amour d’automne (Chaminade) | 3:03 |

| xP 1044 (33908) | ||

| 14. | Si tu veux, mignonne (Massenet) | 2:54 |

| xP 1045 (33909) | ||

| 15. | Si tu veux, mignonne (Massenet) | 2:53 |

| xP 1045-2 (33909-2) | ||

| 16. | Extase (Salomon) | 3:09 |

| xP 1046 (33902) | ||

| 17. | Les deux cœurs (Fontenailles) | 3:19 |

| xP 1047 (33910) | ||

| 18. | Plaisir d’amour (Martini) | 3:16 |

| xP 1049 (33911) | ||

PANTOPHONE DISCS, PARIS, MARCH 1905 | ||

| 19. | Amour d’automne (Chaminade) | 2:57 |

| 13 March 1905; 1863 (1863) | ||

| 20. | Le sais-tu bien? (Pierné) | 3:11 |

| 20 March 1905; 1913 (1913) | ||

| All tracks are with piano except track 11, which is with orchestra | ||

| All tracks sung in French | ||

CD 3 (72:21) | ||

Max Bouvet | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDERS (SOME LATER REISSUED AS DISCS), PARIS, CA. MARCH 1903 | ||

| 1. | JOCONDE: Dans une délire extrême (Isouard) | 2:23 |

| 2590 (21cm center-start disc 2590 [23483 R]) | ||

| 2. | Cantique de Noël (Adam) | 2:27 |

| 2591 (29cm center-start disc 2591 [18501 BC]) | ||

| 3. | RICHARD CŒUR-DE-LION: Ô Richard, ô mon roi (Grétry) | 2:10 |

| 2592 (molded Inter cylinder 2592 [8058]) | ||

| 4. | LE PARDON DE PLOËRMEL: Ah! mon remords te venge (Meyerbeer) | 2:08 |

| 2593 (molded Standard cylinder 2593 [10334]) | ||

| 5. | HAMLET: Spectre infernal (Thomas) | 2:16 |

| 2594 (21cm center-start disc 2594 [23469 R]) | ||

| 6. | Le soir (Gounod) | 2:07 |

| 2598 (24cm center-start disc 2598 [5084 C]) | ||

| 7. | LAKMÉ: Lakmé, ton doux regard se voile (Delibes) | 2:03 |

| 2599 (molded Standard cylinder 2599 [3733]) | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDER (LATER REISSUED AS DISC), PARIS, CA. APRIL 1904 | ||

| 8. | LAKMÉ: Lakmé, ton doux regard se voile (Delibes) | 2:07 |

| 2599 (29cm center-start disc 2599 [20366 BC]) | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDERS (LATER REISSUED AS DISCS), PARIS, DECEMBER 1904 | ||

| 9. | Le crucifix (Faure) | 2:13 |

| with Albert Vaguet, tenor | ||

| 3760 (29cm center-start disc 3760 [44274 GR]) | ||

| 10. | Le crucifix (Faure) | 2:21 |

| with Albert Vaguet, tenor | ||

| 3760 [alternative take] (29cm center-start disc 3760 [17961 BC]) | ||

PATHÉ CENTER-START DISCS, PARIS, CA. OCTOBER 1907 | ||

| 11. | PHILÉMON ET BAUCIS: Que les songes heureux (Gounod) | 3:01 |

| 4900 (29cm center-start disc 4900 [19816 BC]) | ||

| 12. | TANNHÄUSER: O du mein holder Abendstern (Ô douce étoile, feu du soir) (Wagner) | 2:36 |

| 4901 (29cm center-start disc 4901 [19824 BC]) | ||

| 13. | JOCONDE: Dans une délire extrême (Isouard) | 2:25 |

| 4902 (29cm center-start disc 4902 [20385 BC]) | ||

Maurice Renaud | ||

PATHÉ CYLINDERS, PARIS, CA. NOVEMBER 1902 | ||

| 14. | CARMEN: Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre (Bizet) | 2:17 |

| 3381 (molded Inter cylinder 3381 [21660]) | ||

| 15. | LA DAMNATION DE FAUST: Voici des roses (Berlioz) | 2:27 |

| 3383 (molded Inter cylinder 3383 [7842]) | ||

| 16. | Le soir (Gounod) | 2:18 |

| 3384 (early molded Standard cylinder 3384) | ||

| 17. | SIGURD: Et toi, Fréïa (Reyer) | 2:20 |

| 3386 (molded Inter cylinder 3386 [477]) | ||

| 18. | TANNHÄUSER: O du mein holder Abendstern (Ô douce étoile, feu du soir) (Wagner) | 2:30 |

| 3387 (molded Standard cylinder 3387 and 29cm paper-label disc 0189) | ||

PATHÉ CENTER-START DISCS, PARIS, CA. SEPTEMBER 1906 | ||

| 19. | CARMEN: Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre (Bizet) | 2:29 |

| 3381 (21cm 3381 [3532 GR]) | ||

| 20. | CARMEN: Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre (Bizet) | 2:18 |

| 3381 [alternative take] (29cm paper-label disc 0037) | ||

| 21. | LE ROI DE LAHORE: Promesse de mon avenir (Massenet) | 3:39 |

| 3382 (29cm center-start disc 3382 [32191 R]) | ||

| 22. | LA DAMNATION DE FAUST: Voici des roses (Berlioz) | 3:16 |

| 3383 (29cm center-start disc 3383 [11846 P]) | ||

| 23. | Le soir (Gounod) | 2:45 |

| 3384 (29cm center-start disc 3384 [36093 G]) | ||

| 24. | LA FAVORITE: Léonor, viens, j’abandonne Dieu (Donizetti) | 3:42 |

| 3385 (29cm center-start disc 3385 [44800 GR]) | ||

| 25. | SIGURD: Et toi, Fréïa (Reyer) | 3:08 |

| 3386 (29cm center-start disc 3386 [41990 GR]) | ||

| 26. | TANNHÄUSER: O du mein holder Abendstern (Ô douce étoile, feu du soir) (Wagner) | 3:11 |

| 3387 (29cm center-start disc 3387 [11834 P]) | ||

Appendix 1: Two cylinders allegedly sung by Jean-Baptiste Faure | ||

BROWN-WAX CYLINDERS OF UNIDENTIFIED PROVENANCE, PARIS, CA. 1900 | ||

| 27. | LA FAVORITE: Jardins de l’Alcazar! ... Léonor, viens, j’abandonne Dieu (Donizetti) | 3:03 |

| 28. | Cantique de Noël (Adam) | 2:42 |

| brown-wax cylinder inscribed “Cantique de Noël (14) Mr J. B. Faure” (“857” stamped on box) | ||

| All tracks are with piano except tracks 11-13, which are with orchestra | ||

| All tracks sung in French | ||

Producers: Ward Marston and Scott Kessler

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston, J. Richard Harris, and Christian Zwarg

Photos: Girvice Archer, Gregor Benko, Luc Bourrousse, Harold Bruder, Peter Clark (Curator of the Metropolitan Opera Archive), Richard Copeman, Paul Steinson, and Barbara Tancil

Booklet Coordinator: Mark S. Stehle

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Foreword: William Crutchfield

Booklet Notes: Luc Bourrousse

This project has been partially funded by Francisco Luis Segalerva Cabello, John L. Frigo, G. Ronald Kastner, Ph.D., William Russell, and Robert G Simon.

Marston would like to thank the following for making recordings available for the production of this set: Gregor Benko, Henri Chamoux, Dominic Combe, Richard Copeman, Harry Glaze, Lawrence F. Holdridge, John Humbley, David Schmutz, Paul Steinson, and Christian Zwarg.

Marston would like to acknowledge the late Richard Warren, former curator of the Yale Collection of Historical Sound Recordings at Yale University Library, for making available cylinders and discs for this project.

Marston would like to thank William Crutchfield and Christian Zwarg for their editorial guidance.

Marston would like to thank Christian Zwarg for his invaluable help with providing important discographic information. Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

FOREWORD

by Will Crutchfield, © 2020

Everyone who has dipped into the field of historical recordings knows that they are our priceless clue to what opera sounded like when it was in its prime as a creative form. And everyone who has delved far enough to get a sense of the different styles in existence knows that there was something particular about French baritones. Each of the singers heard here had his own artistic personality, of course—and his own strengths and weaknesses—but as a group they teach us an approach that we have practically never heard in our own live opera-going experience.

To put it in a nutshell: the greatest achievable power channeled through the strictest possible discipline. These baritones don’t do “fat” high notes; they don’t roar; they don’t lose their cool. Some of them, at times, sound to a casual modern ear more like lyric tenors. We might even suspect their voices were smallish, yet we know they sang big roles with big orchestras in big theaters, and thrilled the public doing so. The closer we listen the more clearly we can hear how. Their ideal was a firmly focused, balanced tone that never, never, never lost its core resonance, while at the same time seeking its artistic effects within a range that never jeopardized complete control of the instrument. In one sense, this makes for a more restricted palette of colors and dynamics than we might enjoy in the Chaliapins, Carusos, Schumann-Heinks, and other extravagant glories of the old-records era. But if we focus our own ears as they did their voices, the satisfactions are great. For one thing, we can hear the vigor and subtlety of classic French declamation as an ally and not an opponent of perfect vocal sound. For another, we can admire the shape and cut of the relatively simple vocal lines favored by the French composers of the day when we hear them so precisely pitched and etched by voices that are never on the edge of roughness or approximation. We can also appreciate a technical approach that regards the high end of the baritone range as a field for controlled flexibility: not developed to exceed the middle voice greatly in volume, but rather cultivated for ease of handling. The higher voices in the group can “talk” on upper E, F, F-sharp, and G as though no particular difficulty were involved, and even the more bass-shaded baritones can do this at nearly the same altitude. But the insistence on core tone and the rigor of its continuity completely evades the whispery, flimsy impression that we sometimes receive when later singers occasionally mimic the surface attributes of this style. The standard of elegance here is un-showy but very high.

Once the principles are outlined in that exacting way, it is easy enough to note that they were not achieved perfectly by every singer in every record. But one would have to look far for a community of vocalists as consistent as this one at keeping its ideals in view. They help us to understand how French opera was such a dominant component of the international mix in the last quarter of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth, and show us what might be involved in a true revival of a repertory that meant so much to so many at the time.

THE LEGACY OF JEAN-BAPTISTE FAURE:

LÉON MELCHISSÉDEC, JEAN LASSALLE, MAX BOUVET,

AND MAURICE RENAUD

By Luc Bourrousse, ©2020

JEAN-BAPTISTE FAURE (1830–1914)

What could be more evocative of the French art of singing than the baritone voice? From Martin to Dabadie to Barroilhet, France contributed decisively to the evolution of the Fach, before giving birth to its exponent in excelsis, Jean-Baptiste Faure. His formidable shadow hovers above all of his contemporaries and successors: Faure was successively the first Nélusko (1865), Posa (1867), Hamlet (1868), the first Paris Opéra Méphisto (1869), and the reigning Don Giovanni, Tell, and King Alphonse in La favorite, compelling Lassalle to wait in the wings, and Jules Devoyod (1841–1901) or Victor Maurel (1848–1923) to seek their fortunes elsewhere, successfully in both cases. Though Lassalle’s senior, Melchissédec would not reach the Opéra before 1879; by then Faure had left, touring the provinces, teaching, composing scores of songs such as “Le crucifix” and “Les rameaux,” and writing his treatise La voix et le chant, a lavish affair published by Heugel in 1885, dedicated to former and first French Arts Minister Antonin Proust and embellished with an elegant engraved portrait—a far cry from the rambling books on singing Melchissédec would later commit.

In many respects Faure was the perfect embodiment of this nineteenth century that sociologists now consider began after Charles X’s reign and came to its crashing end with the First World War—and he would not survive it: he died appropriately on the eve of the conflict, on 9 November 1914, having been born no less appositely on 15 January 1830, in Moulins. Like his contemporary Caroline Miolan-Carvalho (1827–1895), he was more than a star: an authority; their singing defined the art of their times. Both displayed a virtuosic mastery of coloratura and were above all the perfect exponents of chant lié et soutenu, sustained and legato singing, blending clarity of elocution, smoothness of delivery, and supreme finish of the musical line in an entrancing whole. Both were also equally fluent in the different styles of the two leading French houses, the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique; indeed, it was at the Opéra-Comique that, after claiming first prizes in singing and opéra-comique at the Conservatoire, Faure made his debut on 20 October 1852 as Pygmalion in Massé’s Galathée. He would remain there for almost eight years, creating works by Auber, Grisar, Clapisson as well as Hoël in Le pardon de Ploërmel, aka Dinorah (1859), and marrying soprano Caroline Lefebvre1 (who had taken part in the creation of L’étoile du Nord; a grateful Meyerbeer was a witness), before switching to the Opéra and reigning there for fifteen years, until 1876.

The Spring Italian seasons in London proved a prestigious stepping-stone between the two French houses: Faure made his Covent Garden debut in 1860 (followed by an uncharacteristically failed one in Berlin in November), and returned the following year, after being signed by the Paris Opéra in early 1861. He would remain a frequent visitor to London until 1877, whether at Covent Garden, Drury Lane, or Her Majesty’s Theatre, cultivating the Italian repertoire (Iago in Rossini’s Otello, Assur in Semiramide, Alfonso d’Este in Lucrezia Borgia, Ashton in Lucia). The 1870s saw him as a regular guest at La Monnaie in Brussels (where he introduced Hamlet in 1871), giving occasional performances in neighboring Belgian and Dutch cities such as Antwerpen, Den Haag, or Liège, and the Wiener Hofoper welcomed him rapturously in 1878 (he was made a Kammersänger by Emperor Franz Joseph). He also performed in Geneva (1880) and Monte-Carlo (1880, 1882, and 1885).

Faure’s last recorded stage appearances took place in 1886, first in Marseilles and Montpellier, then in July in Vichy, an important summer resort not far from his native Moulins, in Faust and La favorite with Blanche Deschamps. Extremely active as a concert and church singer all his career long (he had actually begun singing as a choirboy), he could occasionally be heard until at least 1903, when he sang at writer Ernest Legouvé’s funeral. Faure was a noted art collector and patron, amassing (and selling) numerous works by the likes of Delacroix, Ingres, Degas, and Monet, and commissioning portraits from Boldini, Manet, and Zorn.

THE ALLEGED FAURE RECORDINGS

. . . . .

In the first pages of his 1923 biography of Faure, Henri de Curzon, who had known him late in life, describes a singer slightly haunted by the “vanity of his past celebrity,” doing away with mementos and souvenirs; he adds, “a fortune would not have convinced him to abandon his voice to the phonographs.” Of course, this doesn’t preclude the possibility that the aging legend made private recordings that his son Maurice, who died a few months after his father, would have had neither the idea nor the time to destroy; in fact, two primitive cylinders have surfaced which have been attributed to Faure. One is a shortened version of King Alphonse’s Act 2 scene in La favorite, and that in itself is already suspicious; it is dubious that the fastidious singer, in his seventies or late sixties, would have chosen such a demanding piece for the sake of a trial recording rather than one of his well-rehearsed triumphs: Faure’s acknowledged supreme moment in the opera was the arioso from the Act 3 trio (“Pour tant d’amour”), as attested, among others, by Max Bouvet’s exquisite homage to Faure in his own 1907 singing method. The cylinder announcement is obviously incomplete, missing a first part naming the opera, and distinctly coarse in its theatrical emphasis; the unnecessary article “le” only adds to the inelegance.

The singing is on a par with the announcement. While the voice, a high baritone sounding neither old nor young, is not fundamentally poor, the singer has glaring breath support issues, matched by ones of textual accuracy, and even pronunciation ones: his French is simply not good enough, with awful pinched “es” and “eus.” The tinkering with words is mostly harmless (an added “et,” “changer” instead of “finir”) but perfectly unnecessary; as for the singing itself … no trill, laborious ornaments, intakes of breath everywhere, from the very beginning (between “Jardins” and “de l’Alcazar”, which is absurd), to a dubious achievement of no less than three respirations in a phrase (“que ton cœur, que ton cœur à moi se donne”) that calls at best for one, and is written without any. The over-emphatic delivery compounds the failure. Whether this is an amateur, a not-so-bright student, or a third-rate professional is irrelevant: it certainly cannot be Faure.

The other recording is quite another thing. From under the noisy surface emerges a steady, unforced voice; the text is flawlessly enunciated, with perfect mute “es” and without overemphasis. The tone is at once more sedate (as befits the piece, a favorite Faure encore) and more patrician (as would have greatly benefitted the Favorite scene). Always perfectly sustained on the breath, the phrases flow organically from each other: this is a beautiful recording of classic purity, almost the exact opposite of the asthmatic bellowing of the other cylinder. Nothing really warrants an attribution to Faure, but the performer is certainly an excellent professional singer.

LÉON MELCHISSÉDEC (1843–1925)

Like Faure, Melchissédec reached the Paris Opéra after the Opéra-Comique, though his path was more circuitous. Two of his paternal uncles, Guillaume and Léon the elder, were both bass-baritones of no mean abilities but uncertain health (none of them reached his fiftieth birthday); indeed, the younger Melchissédec’s longevity can be seen as a kind of familial vindication.2 Both uncles had serious careers, singing in important provincial houses: Alger, Nancy, Avignon, Lille, and Nîmes for Guillaume (1821–1870), credited with typical Melchissédec versatility and rumored to have once sung the tenor part of Masaniello in La muette de Portici, and the following day the bass part of Balthazar in La favorite; Montpellier, New Orleans, Ghent, Marseille, Rouen, Lyon, Bordeaux, Toulouse for Léon the elder (1825–1874), who composed the occasional romance, was married to actress Louise-Amélie Chalain (1825–1892) and was briefly considered by the Opéra-Comique.3

Léon the younger was born Pierre-Léon on 7 May 1843, in Clermont-Ferrand. At twenty he entered the Paris Conservatoire, studying singing with Henri(-Paul-Pierre-Marie) Laget (1821–1875), a bass whose own precarious health prevented him to lead the career a successful Opéra debut seemed to augur, and déclamation lyrique with Levasseur and Mocker. The 1865 examination brought him a second accessit in singing and two second prizes in opéra and opéra-comique, followed by an engagement at the Opéra-Comique where, after due coaching, he made his debut—as usually mentioned (see footnote 3)—on 16 July 1866 as Don Fabio in the premiere of Jules Cohen’s José-Maria. Melchissédec’s repertoire at the Opéra-Comique encompassed classic baritone fare (Belamy in Les dragons de Villars, Jean in Les noces de Jeannette, Ourrias, Barnabé in Le maître de chapelle, Blondel in Richard Cœur-de-Lion [as a mock minstrel, he played the violin himself], Pandolphe in La servante maîtresse), a tenor role (he was the first baritone to attempt Zampa at the Opéra-Comique) and quite a number of typical première basse d’opéra-comique parts (Sulpice in La fille du régiment, Girot in Le pré-aux-clercs, Max in Le chalet, Michel in Le caïd) which made good on his bonhomie but exposed a comparatively weak low register. A vivid performer, he was sought after for creations, which included Offenbach’s Robinson Crusoé (1867) and Fantasio (1872), and Auber’s Le premier jour de bonheur (1868). It might have been to escape miscasting in bass roles that Melchissédec left the Opéra-Comique in 1876 to join the Théâtre-Lyrique, where his debut took place as Lusace in Joncières’s Dimitri, a role premiered by Lassalle at the same theater the previous season. After creating Massé’s Paul et Virginie (1876) and Saint-Saëns’s Le timbre d’argent (1877), Melchissédec left the Théâtre-Lyrique for Naples, where he fell ill and did not sing. Back in Paris, he premiered at the salle Ventadour Pessard’s Le capitaine Fracasse (1878), in which he took the title-role, alongside Taskin and Eugénie Vergin.4

He finally appeared at the Paris Opéra, as Nevers in Les huguenots, in November 1879, a few days before Maurel’s long-delayed rentrée (after ten years) as Hamlet. Their respective status was thus clear: Maurel as co-successor, together with Lassalle, to the departed star, Faure (who was rumored to have made the absence of Lassalle a condition of his own presence at the Opéra); Melchissédec was more of an ensemble player. He would indeed prove invaluable to the house, not only as an understudy to the variously unreliable Lassalle and Maurel, but also as a dependable performer in his own right, really coming into his own as Guillaume Tell (a more likely incarnation of the Swiss mountain dweller than Faure’s). He took part in three creations: Pessard’s Tabarin (1885), Gounod’s Le tribut de Zamora (1881), and Massenet’s Le Cid (1885), in which he had relatively minor roles. He would soon, however, substitute for Lassalle in Le tribut de Zamora, just as he had taken over from Maurel as Amonasro after the house premiere of Aida (1880). Melchissédec also sang Alcée in the new version of Gounod’s Sapho (1884) and, after having sung Capulet at the Opéra-Comique for the house premiere of Roméo et Juliette (1873), was the first Opéra Mercutio when Gounod’s work entered the Palais Garnier’s repertoire with Patti and Jean de Reszke (1888). Other notable parts included King Alphonse in La favorite, Raimbaud in Le comte Ory, Valentin, Nélusko, Malatesta in Thomas’s Françoise de Rimini, Rigoletto, Gunther in Sigurd, and Rysoor in Patrie.

Melchissédec left the Opéra after the summer of 1891 (he nevertheless took part in the celebration of Meyerbeer’s centenary on 14 November as Nélusko in the first act of L’Africaine) and signed with Monte-Carlo. He made his debut there as Rigoletto on 16 February 1892, and would return every year until 1900. Besides classic assignments (La favorite, Aida), highlights include the famed Gunsbourg production of La damnation de Faust (1893, with Jean de Reszke and Emma d’Alba), a revival of Halévy’s La reine de Chypre (1893), the local premiere of De Lara’s Amy Robsart, in which he sang another Lassalle-initiated role (1894), a rare Telramund (1894), the creations of César Franck’s Ghiselle (1896), and of De Lara’s Moïna (1897), and Messaline (1899).

Melchissédec’s last stage appearance of note, at the Bouffes-Parisiens in 1902, was a kind of cameo, as an old gruff soldier in Justin Clérice’s Ordre de l’Empereur! alongside Charlotte Mellot (later Mellot-Joubert, 1877–1958), soon to leave the Opéra-Comique, and Henri Dutilloy, who was about to join it. By then, the older baritone had been teaching déclamation lyrique at the Paris Conservatoire since October 1894 and would mostly appear on the concert stage rather than in theaters, as late as 1921. He retired from the Conservatoire in 1924 (he was succeeded by Albert Carré), and died only a few months later on 23 March 1925. He left countless articles and essays as well as two books on singing, Pour chanter—ce qu’il faut savoir (1913) and Le chant (1925).

THE MELCHISSÉDEC RECORDINGS

. . . . .

Melchissédec’s discography provides a good overview of his extensive repertoire, but regrettably, most of his Pathé cylinders, nearly two-thirds of his recorded output, have not surfaced. What survives, though, gives a reasonably accurate idea of the singer. The first known item, an excerpt from Le caïd that he recorded three times, is a case in point. In the two extant recordings he makes the same trivial but clumsy alteration to the text (“les militaires” instead of “le militaire”); on the other hand, this lack of sophistication serves the character rather better than Plançon’s ornateness. The Berliner disc shows a good voice without any obvious weakness in the low register, exhibiting mostly excellent elocution and nice trills. It should be noted, however, that he does alter the line to avoid descents to low G and F-sharp. (The Pathé cylinder in excellent sound for the time is a curio as Melchissédec sings the aria without accompaniment.) Indeed, the good voice remains on display in most of Melchissédec’s recorded legacy.

On Zonophone, Melchissédec uses the Guillaume Tell prayer to expound his interpretative and technical ideas, assuming both his own teacherly voice and that of a supposed pupil. There are two versions of this “Leçon de chant,” a ten-inch one and an abbreviated seven-inch one; they remain quaint tours de force-cum-manifesto more than valid renditions. One would have to turn to his 1899 Pathé recording for that, but unfortunately it has not come to light. In fact, only one cylinder from that first series has been located. The other extant Pathé cylinders heard here are all from 1902. If Valentin’s aria is a stretch, both up and down, the two versions of a pleasantly sarcastic Méphistophélès serenade hint at how tiresome recording cylinders was: each shows a different mistake in the words. But the Dragons de Villars excerpts are a demonstration, if not precisely of style, at least of genuine opéra-comique spirit; mercifully free of mannerisms and mugging, they show Melchissédec at his vivid, very enjoyable best. His Zonophone and Pathé versions of La Marseillaise, which he often sang at the Opéra free matinée on National Day (on occasion in a military uniform) are suitably vibrant.

The APGA sessions of 1907–1908 were Melchissédec’s last, and not his best: by then he was nearing sixty-three and had been singing for more than forty years, and some amount of fatigue is only to be expected, especially as far as pitch is concerned. The Bal masqué aria is a trial in this respect (though the softness of its opening lines is a nice touch), but Rigoletto’s arioso goes much better, and so do the arias from L’Africaine, even if the recording tends to blur the articulation. The rubato in Don Juan will be a matter of taste, and he ends it on the added high note familiar from Renaud’s 1906 G&T recording. The Roméo selection has its problems (an unfortunate liaison,5 weak low notes, not quite fluid emission) but is carried along by the sheer aptness, naturalness, and mere charm of the incarnation.

JEAN LASSALLE (1847–1909)

Born in Lyons on 14 December 1847, Jean Lassalle (his birth certificate bears only this plain “Jean”) first studied as a draughtsman, then entered the Paris Conservatoire the year after Melchissédec left it. He was also a pupil of Laget, and took his first examination in July 1867, singing Procida’s aria from Les vêpres siciliennes. The jury, of which Barroilhet was part, didn’t feel compelled to award him any prizes; Melchissédec, fresh from his successful first Opéra-Comique season and back at the Conservatoire to play opposite some of his former comrades, was the star of the event, and the two revelations of the year had name Gailhard and Maurel—two fellow pupils with whom Lassalle had taken part in the creation of Verdi’s Don Carlos at the Paris Opéra a few months before, as monks in the auto-da-fé scene.

Soon the aspiring singer left the Conservatoire, studying with Édouard Lavessière.6 Lassalle would later claim him as his one and only teacher, and indeed spent his first seasons alongside his mentor, beginning in Liège, where the young baritone made his debut on 19 November 1868 as Saint-Bris in Les huguenots. He was cast as Piétro in La muette de Portici (he and Lavessière enjoying the expected success in the famous duet) and Georges d’Orbel, aka Giorgio Germont, in La traviata, and guested in Lille as Guillaume Tell and as Ezzelin in the local premiere of Maillart’s Lara. 1869–1870 saw the duet in Toulouse, where Lassalle added La favorite, Charles VI, Le trouvère, Nevers in Les huguenots, and Mathisen in Le prophète to his repertoire, while Lavessière was refused (then much fêted during the interim before the arrival of a successor). After Toulouse Lassalle went to Den Haag, or rather to the Théâtre Royal Français de La Haye (a new role was Mercutio in Roméo et Juliette), then in 1871–1872 to La Monnaie in Brussels, where he made his debut as Nevers, sang Telramund, Nélusko in L’Africaine, Hamlet, and Renato in the house premiere of Verdi’s Le bal masqué (Un ballo in maschera had been previously introduced by an Italian company).

His Paris Opéra debut, as Guillaume Tell, took place on 10 June 1872; Nélusko followed, then Nevers, but Lassalle only rarely performed (mostly in summer) during his first seasons at the Opéra. The first premiere in which he took part, Membrée’s L’esclave (15 July 1874), was a failure, but more successful ones would follow. The first ones took place outside of the Opéra: at the Cirque d’Été, where he introduced Massenet’s oratorio Ève alongside Marie-Hélène Brunet-Lafleur, the lady’s husband, Charles Lamoureux, conducting (1875); and at the Théâtre-Lyrique, where the Opéra management allowed him to take part in the creation of Joncières’s Dimitri (1876). Then, Faure having left, came a string of Opéra creations: Massenet’s Le roi de Lahore (1877), which would launch Lassalle’s international career, Gounod’s Polyeucte (1878) and Le tribut de Zamora (1881), Thomas’s Françoise de Rimini (1882), and Saint-Saëns’s Henry VIII (1883) and Ascanio (1891).

Lassalle introduced Le roi de Lahore to La Scala audiences in February 1879, then to London in June of the same year: he would return to Covent Garden in 1880 and 1881 (starring in the first British performance of Rubinstein’s Demon, in Italian, with Albani, under the composer’s baton), then between 1888 and 1893, creating De Lara’s The Light of Asia (1892) and Amy Robsart (1893). Madrid welcomed him in 1879, the Wiener Hofoper in 1886, and New York between 1892 and 1897 (with the occasional performances in Philadelphia, Boston, and Chicago). The Metropolitan Opera offered him a number of unusual roles including Hoël alongside Van Zandt in the first local performance of Dinorah (Magini-Coletti sang the company premiere on tour in Chicago), and various Wagnerian incarnations, notably Wolfram and the Dutchman (Sachs he first essayed at Covent Garden). During his last campaign in New York, he also introduced the Melchissédec part of the King in Massenet’s Le Cid.

In between those foreign engagements Lassalle would guest in the French provinces and

continue to appear at the Opéra, albeit somewhat sporadically, though he found the time to sing in two Opéra premieres, Reyer’s Sigurd (Gunther, 1884) and Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila (High Priest, 1892); he also took part in the December 1890 gala performance of Carmen at the Opéra-Comique with Galli-Marié, Melba, Jean de Reszké, and prima ballerina Rosita Mauri—the proceeds going to the Bizet monument by Falguière now standing in the Salle Bizet at the Opéra-Comique.

1898 was the year of Lassalle’s final stage performances, as Tell, Nélusko, Don Juan, and Gounod’s Méphistophélès, during a German tour from Straßburg to Berlin by way of Frankfurt, Wiesbaden, and Köln. He remained for a few months in Berlin, singing both at the Staatsoper and at the Kroll Theater, before embarking with pianist Alfred Sormann for a concert tour of summer resorts, including Salzburg. Back in Paris, he continued to appear regularly in concerts before opening a singing school in 1900; three years later, he was appointed to the Paris Conservatoire, and in November 1907, married one of his pupils, mezzo-soprano Suzanne Faye (1885–1976)7 who had just made a successful Opéra-Comique debut as Charlotte, and bore him a daughter, Nicollette-Andrée (1908-1984). Lassalle had never actually wed Anna “Jeanne” Piotruszynska (1852-1888), the mother of his elder children. Of these, Robert, born on 3 March 1882, had a creditable career as a tenor. After studying under Pericles Aramis, Robert made his debut as Canio at the Teatro Lirico in Milano in 1910, sang in Biarritz, Boston, then at the Paris Opera. After World War I, in which he fought with distinction, he spent a few seasons in Bordeaux, Alger, Marseille, and Mulhouse, and appeared as a guest in the French provinces, in Liège, and Barcelona. His last appearance of note was as Samson in Marseille in 1926. He was married to singer Andrée Allard and died on 21 November 1943. His younger brother Nicolas (1884–1957), also a pupil of Aramis, had a brief career as a bass, mainly in the French provinces (Angers, Marseille, and Bordeaux).

THE LASSALLE RECORDINGS

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Lassalle’s voice has always been problematic and was frequently discussed during his whole career. Laget might have been overcautious in giving him a bass aria for his first examination, but years later Shaw would liken him to Édouard de Reszké and label them bassi cantanti; by the time of the Henry VIII premiere in 1883, high notes were already a challenge. At Covent Garden, in 1890, he transposed “Cortigiani” a whole tone down, and by the time he came before the recording horn, twelve years later, things were unlikely to have improved —the fact is that for his 1904 Odéons and 1905 Pantophones Lassalle kept himself safely to songs. His Pathé recordings of 1902–1903 were at once more diverse and maybe more testamentary, with a few opera excerpts, including two creator’s records (Le roi de Lahore and Ascanio); all of these are transposed down, from a semitone (Don Giovanni) to a major third (Ascanio), the only exception being Wolfram’s “Romance de l’étoile”. In spite of this, they make for a rather haunting set: the clear enunciation (several word changes in Le roi de Lahore notwithstanding), legato, soft and sustained singing are of a great artist; the tenderness and melancholy of a very individual one; as for the beauty of the voice, especially in the pianissimo, it was never in dispute —though this is admittedly a very subjective notion. The narrower vocal ambit of the songs allows the singer more interpretative liberty and variety than the somewhat guarded opera selections. Of course the somber renditions of “Plaisir d’amour” are distinctly un-classical in mood, but on the whole Lassalle emerges as both a dramatic and sober interpreter, never emphatic, maudlin or mannered, making subtle expressive use of a strong low register and a captivating pianissimo. Unlike the shortened Pathé one, the Odéon version of Massenet’s “Chant provençal” displays a lovely head-voice G-flat, and indeed the Massenet and Chaminade songs are stylistic perfection, and Rubinstein’s Op. 8, No. 5 is quite a success: Lassalle’s recordings certainly repay close and repeated listening.

MAX BOUVET (1854–1943)

Third in this line of slightly temperamental baritones, Max Bouvet was born Nicolas-Maximilien Bouvet in La Rochelle on 3 December 1854. Having reached the Paris Conservatoire in 1873, he studied with Laget and Mocker but failed to be admitted to any examination and left, signing a three-month engagement with the Eldorado in July 1875 and joining the lineup at the celebrated café-concert as Max. There he sang the typical mix of songs by Henrion, Bordèse, and Faure, and arias from La favorite, Le trouvère, and Dom Sébastien. By the end of October, he was off to military service in Cambrai, from which he emerged in the fall of 1877 as opéra-comique and operetta baritone in Liège. The following season he was refused in both Den Haag and Antwerp; the latter city welcomed him in 1880–1881. After that came a short opéra-comique season at the Teatro Lirico in Barcelona, where he sang Belamy to Galli-Marié’s Rose Friquet in Les dragons de Villars, and Escamillo to her Carmen in the Spanish premiere of Bizet’s opera on 2 August 1881.

The astute Tancrède Gravière, first husband of Georgette Bréjean, snatched Bouvet for the 1881–1882 season in Geneva.8 After a summer season in Luchon, the baritone made his debut at the Folies-Dramatiques in Paris on 21 October 1882, creating the title role in Varney’s Fanfan la Tulipe alongside Simon-Max and his wife, Juliette Simon-Girard. Success was immediate, further strengthened by runs of Les cloches de Corneville and La fille de Madame Angot, and two more creations, Amédée Godard’s L’amour qui passe and Bernicat’s and Messager’s François les bas-bleus, both in 1883. Bouvet also appeared at the Galeries Saint-Hubert in Brussels, Bordeaux, and at the Gymnase in Marseille, before joining the Opéra-Comique.

Bouvet’s debut, like Hippolyte Belhomme’s, took place during the notorious house premiere of Rossini’s Barbier de Séville (8 November 1884), when an unwell Marie van Zandt had to be replaced by Cécile Mézeray in rather murky circumstances. Once the dust had settled, Figaro was found quite satisfactory, and Bouvet would keep the part in his repertoire until the very end of his career.9 He served two terms at the Opéra-Comique. During the first one, he took part in a number of creations, introducing Rudolf in Joncières’s Le chevalier Jean (1885), the title-part in Widor’s Maître Ambros (1886), Henri de Valois in Chabrier’s Le roi malgré lui (1887), Karnac in Le roi d’Ys (1888), and the Bishop of Blois in Esclarmonde (1889). He sang d’Orbel in the house premiere of La traviata and starred in revivals of Grétry’s Richard Cœur-de-Lion and of Meyerbeer’s Le pardon de Ploërmel, with Cécile Merguillier as Dinorah.

The change of director following the fire of May 1887 brought in former bass-baritone Louis Paravey as director, and a number of singers left: Bouvet went to Brussels—as did Merguillier and tenor Bertin—which allowed La Monnaie to revive Le pardon de Ploërmel for its 1889–1890 season’s opening night with the same cast as the Opéra-Comique. Bouvet went through the whole spectrum of baritone roles in two seasons, from Figaro to Siegfried’s Wanderer (a Monnaie premiere, 1891) to Hamlet, Rigoletto, Valentin, and King Alphonse in La favorite. Highlights included the house premiere of Esclarmonde, the creation of Reyer’s Salammbô alongside Rose Caron, and a specifically devised revival of Don Juan prompting, after Hamlet, even more comparisons with Faure. Meanwhile, Carvalho had been reinstated at the head of the Opéra-Comique, and the Belgian émigrés flew back home, or at least to the former Théâtre-Lyrique, which housed the company until 1897.

On 18 June 1891, Bouvet added another bishop to his repertoire with Jean d’Hautecœur in Bruneau’s new lyric drama Le rêve, which went to Covent Garden the following October with most of the original cast, who also gave the English premiere of Gounod’s Philémon et Baucis. Bouvet would return to Covent Garden in 1894, sharing Jupiter in Philémon with Plançon, Valentin with Albers and Ancona, and introducing L’attaque du moulin with fellow creator Marie Delna.

Bouvet’s second Opéra-Comique term saw him in classic parts such as Escamillo, Des Grieux senior, and Ourrias in Mireille. He also participated in a variety of creations: world premieres of Bruneau’s L’attaque du moulin (1893) and Vidal’s Guernica (1895); French premieres of Cavalleria rusticana (1891 with Emma Calvé) and Werther (189310 with Guillaume Ibos and Marie Delna); Opéra-Comique premieres of Massenet’s La Navarraise, Lalo’s and Coquard’s La jacquerie and Albert Cahen’s La femme de Claude after Dumas (all three in 1896); Wagner’s Le vaisseau fantôme and Erlanger’s Kermaria (both in 1897); and notable revivals of Massé’s Paul et Virginie, Bizet’s Les pêcheurs de perles, Meyerbeer’s Le pardon de Ploërmel, Méhul’s Joseph, and Monsigny’s Le déserteur. (The noted scholar, Arthur Pougin, 1834-1921, praised Bouvet as the only member of the cast to be true to Monsigny’s style.) He was also able to take a three-months leave to appear at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, in Les pêcheurs de perles with Regina Pinkert, and Andrea Chénier. More leaves of absence were needed when in 1899 Bouvet became director of the Palais d’Hiver at Pau, where he sang and would remain in charge until 1902.

Bouvet left the Opéra-Comique for good in 1900, having added Oreste in Iphigénie en Tauride (a house premiere with Rose Caron) to his repertoire. From then on he would mostly guest, sometimes as far as Lisbon where in 1904–1905 he starred with Adriana Palermi in the local premiere of Thaïs and appeared as Guillaume Tell, but mostly kept closer to Pau or Paris, where he created Lucien Lambert’s La Flamenca at the Gaîté-Lyrique in October 1903.

In 1894, Bouvet had begun his association with the Monte-Carlo opera: it was there that he introduced Lalo’s and Coquard’s La jacquerie, De Lara’s Moïna (1897; Maurel and Melchissédec were also in the cast, the former a vocal ruin), Rubinstein’s Demon alongside Chaliapin and Arnoldson (1906); he also was Monte-Carlo’s first Alberich (first in Rheingold, 1908, then in the whole Ring, 1909), and, besides the usual Albert and Count Des Grieux, sang Hidraot in Gluck’s Armide, Pizzaro in Fidelio, André Thorel in Massenet’s Thérèse, and the Inquisitor in Don Carlos (1906 and 1907, including the Berlin tour). It is in this last role that he made his final documented stage appearance in 1911 at the Gaîté-Lyrique in Paris, again with Chaliapin.

After Pau, Bouvet briefly took the directorship of the Grand Casino at Dinard (1903), taught déclamation lyrique at the Paris Conservatoire between 1905 and 1911 before resigning and teaching privately in Paris, then in Nice, where he settled between 1923 and 1929. He also authored a volume titled Exercices élémentaires pour le développement et l’assouplissement de la voix (Enoch, 1907). Bouvet was also a prolific painter having studied with Léon Pelouse and Fernand Cormon and some of his works were purchased by the French government. His friend, the Belgian luministe painter Émile Claus (1849–1924), left a portrait of him.

THE BOUVET RECORDINGS

. . . . . . .

In the June 1925 issue of Lyrica, “Mercutio” mentioned Bouvet in a line of “purebred Opéra-Comique baritone[s]” going from Martin to André Baugé by way of “Ismaël, Soulacroix, Bouvet, and Frédéric Boyer.”11 Comparisons are difficult: Soulacroix was a prolific recorder and extrovert performer; Bouvet’s recorded output is limited, and he appears as a rather composed, slightly unhumorous singer (one can’t help wondering about his celebrated Figaro). His two renditions of Joconde’s romance certainly lack Fugère’s exquisite bonhomie, intimacy, and his trill, but they display the same pure vowels, sustained phrasing and considered dynamics, to which Bouvet adds a noticeable subtlety in the execution of liaisons and, of course, a meatier instrument. These qualities are in evidence in all his recorded legacy: the voice is strong along the whole range, the attacks secure whether on delicate piano Es or full blast Fs and Gs, the elocution is true (no “expressively” distorted vowels à la Renaud here), and the style is of perfect classical correctness. There are uncalled-for aspirates in Adam’s “Cantique de Noël” (a rare lapse), the Philémon et Baucis Jupiter has pitch issues, and an admirably sober “Le soir” may feel a bit monolithic to some ears, but Blondel is effectively sturdy, Wolfram superbly sustained, Hamlet suitably dramatic, and Hoël is particularly impressive—no wonder both the Opéra-Comique and La Monnaie entrusted him with the part. Bouvet’s recording of “Le crucifix,” with tenor Albert Vaguet, can be seen as a memento of a benefit performance for the Association de secours mutuels des artistes dramatiques in October 1891,12 and is a beautiful rendition, notable for the smooth relay between the two voices and the way the two singers listen to each other, no mean feat considering the prevailing recording conditions at the time.

MAURICE RENAUD (1861–1933)

Maurice Renaud, born Arnold-Maurice Croneau in Bordeaux on 24 July 1861 (his birth certificate is quite unambiguous), shared with Lassalle and Bouvet the distinction of having left the Paris Conservatoire without earning a prize, and didn’t remain long at the Brussels one either, if he ever set foot there. Like Bouvet, he began by singing in a café-concert, where it seems that he was heard by La Monnaie conductor Joseph Dupont, who sent him to Corneil-Henri Verdhurt (1843–1913), a baritone who had himself studied with Duprez, married Fétis’s granddaughter and would soon become director of La Monnaie and marry again, this time his chanteuse légère Cécile Mézeray—the very lady who had stepped in for Van Zandt in the Opéra-Comique Barbier de Séville.

In July 1883 Renaud was signed by La Monnaie as bass-baritone—the titular baritones were Maurice Devriès and Soulacroix—a third one, Joseph Boussa, must have been deemed in need of assistance (he would later concentrate on the bass repertoire). Young Renaud made his debut on October 11 as Vitellius in a revival of Hérodiade with Rose Caron and, three months later, took part in his first creation, introducing the role of the high priest in Sigurd alongside the same leading lady; he also played Brétigny in the Monnaie premiere of Manon. The following year he was entrusted with Kothner in the local premiere of Les maîtres chanteurs de Nuremberg (Soulacroix was Beckmesser). He spent thus a few seasons developing his voice and art in secondary roles, his breakthrough coming in November 1886 with the Brussels premiere of Lakmé, in which he sang the part of Nilakantha to great acclaim. The following season he was promoted to leads like Zurga and Karnac in the Monnaie premieres of Les pêcheurs de perles and Le roi d’Ys: a prestigious career was thus launched, of which Harold Bruder gave a detailed outline in the Marston issue devoted to Renaud’s Gramophone recordings (Marston 52005-2).

Let’s merely mention a few highlights such as the creation of Reyer’s Salammbô (as Hamilcar, he had Bouvet as his slave Spendius) at La Monnaie, 1890. Renaud’s Opéra-Comique debut that same year as Karnac was merely a stepping stone to the Opéra; after introducing Diaz’s Benvenuto in December, he took advantage of Carvalho’s return at the helm to negotiate his move to the Académie nationale de musique, remaining only to dutifully celebrate, on 6 May, the hundredth performance of Lakmé, with Jane Horwitz as the heroine.

His Monte-Carlo debut in April, in Albert Cahen’s semi-failure Le Vénitien, was not exactly a triumph; with Soulacroix, Melchissédec, and Bouvet all firmly entrenched on the shores of the Mediterranean, Renaud would have to wait until 1901—when Melchissédec at last relinquished Méphistophélès in La damnation de Faust (of which he had been the only exponent since 1893)—to return, but now he returned as a star. Besides Méphistophélès and his usual repertoire, from Don Giovanni to Telramund to Rigoletto and Scarpia, Monte-Carlo brought Renaud several creations by Massenet (Le jongleur de Notre Dame in 1902 and Chérubin in 1905), Mascagni (Amica, 1905), Saint-Saëns (L’ancêtre, 1906), Bruneau (Naïs Micoulin, 1907), and Leroux (Théodora, 1907). He also sang in a few unusual titles for the time (Le roi de Lahore and Don Carlos, both with Geraldine Farrar, the latter with Chaliapin and Bouvet as well), and took part in the company’s 1907 Berlin tour, which featured three living French composers in attendance: Saint-Saëns, Massenet, and Leroux. Renaud sang in La damnation de Faust, Don Carlos, Théodora, and the third act of Hérodiade.

He was a leading light at the Paris Opera from his debut as Nélusko on 17 July 1891, and a significant presence as well in London (from 1897) and New York (both with Hammerstein in 1906 and at the Metropolitan from 1910 to 1912). Renaud’s long career is so well documented in the principal histories of this operatic era as to need no further elaboration here.

As regards Renaud’s often mentioned 1893 United States debut in New Orleans, it is nothing but a mistake: the opportunity of crossing the Atlantic when one has just emerged as Lassalle’s worthy rival at the Paris Opéra is rather fanciful, especially as the New Orleans French Opera House was hardly a prestigious theater viewed from France.13 The confusion seems to have arisen from the faulty spelling, in Henry C. Lahee’s Annals of Music in America, of the name of tenor Raynaud, who sang Samson in the New Orleans premiere of Saint-Saëns’s opera; Blanche Mounier was Dalila and the baritone singing the high priest, hailing from Bordeaux indeed, was Gustave Chauvreau.

For a quarter century Renaud remained an established star, dividing his time between the aforementioned houses and guesting wherever he chose, coming back to La Monnaie, returning to the Opéra-Comique for the occasional Dutchman and Don Juan, bringing his Méphistophélès to La Scala for Toscanini or displaying his inimitable Hérode at the Gaîté alongside Calvé. When the war came he was, at fifty-three, too old to be drafted, but nevertheless enrolled as a private and fought his way to the rank of second lieutenant. His distinguished record at the front earned him a croix de guerre and the Légion d’honneur, which he received in 1916, but it naturally took a toll. By 1917 Renaud was back in Monte-Carlo for Hérodiade and La damnation, then signed with the Paris Opéra for two seasons, singing Thaïs (with Marthe Chenal or Germaine Lubin), Rigoletto, Hamlet, Othello (with Paul Franz and Madeleine Bugg), La damnation, Reyer’s Salammbô, and taking part in a benefit performance of Offenbach’s M. Choufleuri restera chez lui with Fugère in his only appearance at the Opéra as Choufleuri, as well as Raymonde Vécart, Fernand Francell, and Félix Huguenet (Juliette Simon-Girard’s second husband). This echoed the benefit organized a few months earlier at the Opéra-Comique, when Lecocq’s La fille de Madame Angot entered the repertoire of the house with an absurdly star-studded cast;14 Renaud also gave a few performances of his celebrated Scarpia at the Salle Favart. There were guest appearances at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, in Nice, Lyon, and Deauville, followed by a series of Massenet’s Cléopâtre (with, in turn, Mary Garden, Suzanne Brohly, and Maria Kousnetzoff) at the Théâtre-Lyrique during the 1919–1920 winter, then Don Juan in Cannes (with Jane Morlet and Ninon Vallin, Reynaldo Hahn conducting) and in Deauville (with Gabrielle Ritter-Ciampi, and Morlet and Hahn again), where he also sang in Le jongleur de Notre Dame. The following year he was back in Monte-Carlo for La damnation, after which he turned sixty and seems to have retired, though in no way remaining idle, and sitting regularly as a judge for the annual Paris Conservatoire examinations, up until 1933. He died in October of the same year, a few weeks after Marcel Journet and Jean-François Delmas.

THE RENAUD PATHÉ RECORDINGS

. . . . .

Renaud recorded seven two-minute cylinders for Pathé in 1903, and the same selections were subsequently issued by the company in disc format. For years, collectors have assumed that the Pathé discs derived from the 1903 cylinders. Now that five of the 1903 cylinders have come to light, it is evident that they are not the same recordings as the issued Pathé discs. Research by Christian Zwarg indicates that the disc recordings were made in 1906. The five known 1903 cylinders, issued here for the first time, are revelatory: they display a unique youthful bloom mostly absent even on Renaud’s G&Ts, evincing a more natural, less covered emission, and much less vowel distortion than on his later recordings. Escamillo’s aria, however, calls to mind the memories of writer and critic Lucien Solvay, claiming that in Renaud’s café-concert years, he sang very much out of tune; we can hear on both recordings that his low notes are neither easy nor quite true, and he is caught shamelessly indulging in his glorious high notes. The aria from La damnation and Gounod’s song “Le soir” show him at his very best, whether in 1903 or 1906; the Sigurd aria, despite the heavy surface noise, is indisputably superior in 1903, with none of the pinched, nasal sound of the later version. Indeed, one craves for the other two cylinders to surface: the 1906 Roi de Lahore disc, while impressive by the command of dynamics and the sheer beauty of the voice, shows much torturing of the line and vowels, and King Alphonse’s aria from La favorite is not without a hasty moment reminiscent of music-hall comic act Charpini & Brancato. The voice, if slightly more rotund than on the 1903 cylinders, remains utterly beautiful, and the phrasing and shading are masterly. The same can be said of the “Evening Star” from Tannhäuser, a lesson in sustained expression, where the numerous breaths never break the overall, yearning line.

All the singers in this set duly followed in the steps of Faure, Bouvet remaining the most closely associated with the Opéra-Comique, and Lassalle the only one to have mostly kept clear from the house and its repertoire. All shone in roles created by their illustrious elder (Hamlet, Nélusko) or associated with him (Don Giovanni, Tell, King Alphonse), and their recordings help trace the characteristics of the baryton de grand opéra voice type which Faure contributed to shape. Evolving in parallel to the Verdi baritone, it kept closer to their common source in the high basses of Dabadie and Barroilhet, and all singers in this set could and did assume roles sitting significantly lower than what is today associated with the term “baritone”. The other aspect of the Faure legacy lies of course in the care accorded to vocal production and the quality of sound, in the chant lié et soutenu which alone allows full expressive liberty: it can be heard (albeit fleetingly) in some Melchissédec recordings like his Don Giovanni serenade, in the soulful pianissimo and exquisite phrasing of Lassalle, in Bouvet’s immaculate classical purity, or in Renaud’s seemingly limitless variety of shadings. These accomplishments certainly deserved to be preserved, studied, and enjoyed.

1 Constance-Caroline Lefebvre (1828–1905), a pupil of David Banderali and François Moreau-Sainti at the Paris Conservatoire, made her debut at the Opéra-Comique in 1849 and remained with the house until 1861. After the birth of her son Maurice (1862–1915), she spent three seasons (1862–1865) at the Théâtre-Lyrique before retiring from the stage. Caroline Lefebvre took part in numerous creations besides L’étoile du nord, including Thomas’s Le songe d’une nuit d’été (1850) and Gounod’s Mireille (1864).

2 The Melchissédecs were indeed a whole dynasty of performers, whose complexity proved challenging even for such a seasoned and thorough researcher as the late Alfred de Cock, who in his profile of Léon Melchissédec for The Record Collector (Vol. 56, No. 1, March 2011) writes: “André [Melchissédec, appointed Director in Ghent] (…) engaged his wife Mme Duval-Melchissédec but also his daughter Anna!” While soprano Camille Duval-Melchissédec (1873–1970) was indeed the first wife of Léon Melchissédec’s son André-Frédéric (1870–1947), Anna (1873–1954) was actually André’s sister, later known as Mme Marquet-Melchissédec after marrying lawyer Fernand Marquet at Chatou (not Ghent); at 29, André was in any case rather unlikely to have a daughter in age to professionally perform parts like Micaëla or Gilda. André and Camille’s daughter, aptly named Andrée-Camille (1897–1962), made her debut in Rouen as Micaëla in December 1926.

3 Mr. de Cock’s statement, at the beginning of his Record Collector essay, that in 1865 “critics totally ignored the young singer [Léon Melchissédec], confusing his name with that of his uncle” unfortunately should be reversed: contemporary critics were very well aware of who was who, likely more so than later researchers, if only because they were actually present in the audience. The 1865 Conservatoire examinations took place on 20 July (singing), 24 (opéra-comique) and 26 (opéra): it would have been impossible for the young laureate to make his debut at the very busy house on 12 August in a role he would have had to be taught entirely, musically, dramatically, and scenically, in a fortnight; besides the Opéra-Comique would have had no reason to press for such a debut, if only because Pierre-Léon showed more promise than achievements, as his second prizes and unimpressive second accessit attest, and was obviously in need of thorough coaching, notably as regards a noticeable Southern accent. It was indeed his uncle François-Léon Melchissédec who made his Opéra-Comique debut on 12 August 1865 as Don Belflor in Le toréador, after a first Paris appearance a few days before as Bazile in Le barbier de Séville. As both performances were reported in La comédie and elsewhere, due tributes were paid to the elder Melchissédec’s career, reputation, and abilities. His second debut as Max in Le chalet did not generate much comment, possibly because it was already known that he would not remain with the house: he went instead to Toulouse where he was bound due to a previous engagement, sang his three debuts, then resigned and joined his wife in Bordeaux. Ill health soon forced him into retirement—his death was mistakenly announced in 1867; a corrective followed, stating that his health was nevertheless very poor (his successful nephew soon provided him with a pension). He died seven years later.

4 Having sung at the Opéra-Comique, Eugénie-Élise Vergin (1854–1941) would later become a renowned teacher under her married name of Mme Édouard Colonne.

5 The absence of comma between “bienvenus” and “amis” in the piano score is a mere misprint; the comma, a grammatical necessity, correctly figures in the libretto and precludes any liaison.

6 Édouard(-Paul-Alexandre) Lavessière (1833–1892) was still rather young and performed mostly in the provinces and in concert halls, including the London Alhambra. A nephew of dramatist and chansonnier Théophile Dumersan, he had sung at the Théâtre-Lyrique opposite Christine Nilsson in La traviata, and taken part in the premiere of Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette as Pâris. From 1870 on, he sang for a few years under the pseudonym of Novelli, then settled in Paris where he taught Léon Gresse, among others, and died unnoticed on 6 July 1892. Lavessière was also a composer of romances and piano pieces and, more to the point, a pupil of Faure.

7 Suzanne(-Germaine-Cécile) Faye, sometimes known as Germaine Faye or Mrs. Faye-Lassalle, sang mostly comprimaria parts at the Opéra-Comique, though she appeared in leading roles in the provinces. She took part, as Herodias’s page, in the first French performances of Strauss’s Salome, staged by Jacques Isnardon (her déclamation lyrique teacher at the Conservatoire) in his own practice auditorium and revived a few weeks later at the Figaro offices with Walther Straram on the piano. In Un demi-siècle d’Opéra-Comique, Stéphane Wolff confuses her with a younger singer, soprano Marcelle Faye (1898–1975), who sang Elsa at the Paris Opera in 1933.

8 Bouvet had wed in 1876 in Westminster a young lady named Marie Faivre, who died some time afterwards; while in Geneva he remarried with dugazon Marie-Françoise Lorant (1854–ca. after 1931), a sister of tenor and future Paris Opera régisseur Vincent Lorant.

9 In 1906, when the charity L’Œuvre française des trente ans de théâtre gave its hundredth gala performance, two acts of Beaumarchais’s Barbier de Séville were acted by the Comédie-Française, and the third act of Rossini’s opéra-comique (the French version being divided in four acts rather than two) was sung by the irreplaceable Bouvet and Fugère.

10 Some six months earlier, excerpts of Werther were presented at the Ministry of public instruction, with Adèle Isaac, Étienne Gibert, Max Bouvet, and Jeanne Leclerc, with the composer at the piano. Of these, Bouvet was the only one to retain his part for the premiere.

11 A “Frédéric Boyer” has long been mentioned in relation to two Pathé cylinders, no. 156 and no. 176. Research by Christian Zwarg suggests the first name does not appear in any Pathé catalogue. No. 156, which has not surfaced yet, is listed as a tenor selection from Wagner’s Les maîtres-chanteurs; two copies are known of no. 176, Iago’s aria from the Paris Opera French version of Rossini’s Othello. In this version of Rossini’s opera, Iago was sung by famed baritone Paul Barroilhet (the aria itself, an interpolation, is a transposed version of Rodrigo’s “Ma dov’è colei …” from La donna del lago); both cylinders are sung by baritone Alexis Boyer. It seems thus likely that no recording by the elder (and more famous) baritone Frédéric Boyer (1849-1925) survives, if he ever recorded.

12 The piece was then sung by seventeen singers: besides Bouvet and Vaguet, these were the composer himself, Melchissédec, Dubulle, Soulacroix, Morlet, Plançon, Boudouresque junior, and tenors Duc, Sellier, Vergnet, Talazac, Clément, Mouliérat, Carbonne, and Gogny.

13 This is merely a constatation: no matter how important the French Opera House might have been to the dilettanti in New Orleans or elsewhere in the United States, and whatever its importance in introducing new works to the country, its rosters by the late-nineteenth century consisted mainly of second-rate singers, with the occasional (generally fading) star. Tenor Edmond Gluck, who sang in New Orleans that same 1893 season and recorded extensively for Edison, is a case in point: his Brussels debut as Vasco de Gama was considered a disgrace for La Monnaie, he barely remained one month in Le Havre, gave only a handful of performances at the Opéra-Comique (his zenith) and seldom lasted the full season wherever he later sang (Genève, Lyon, Bordeaux). The same can more or less be said about most New Orleans singers—to stick to the 1893 campaign, both principal sopranos Ernestine Lematte-Schweyer and Mathilde Jau-Boyer were considered in France decent enough to be called upon when in need of an emergency replacement, but not good enough to be invited back. They basically made careers out of substitutions. Of course the very timing and short duration of the New Orleans season prevented the theater from getting the best French singers (who would much prefer to stay for seven months in any large city of the Hexagon, where they would remain close enough to Paris, and from where they could substitute or guest wherever they wanted), not to mention the problematic trip itself, entailing a number of weeks at sea and possible shipwreck (a whole company perished in the ‘Evening Star’ catastrophe in 1866); as for the opportunities afforded, they were, at best, a return engagement.

14 28 December 1918. Chenal was Mlle Lange; Edmée Favart was Clairette Angot; Francell was Pitou and Marthe Davelli took the tenor role of Pomponnet; the cast was completed by Lapeyrette as Amaranthe, Huguenet as Larivaudière, Renaud as Louchard, Comédie-Française beauties (Gabrielle Robinne, Marie Leconte, Jeanne Provost, Huguette Duflos) and a number of famous actors, actresses, and singers, notably Renée Camia, Jane Renouardt, Maguy-Warna, Max Dearly, Harry Baur, Louis Maurel, Noté, and Dranem, and most of the Opéra-Comique roster, including the unexpected Lucienne Garchery; Reynaldo Hahn conducted. A repeat performance was given on 18 January 1919.

WARD’S NOTE

This project all began in 1996 when I purchased a group of about forty cylinders, all by French singers, from Michael Gunrem, a dealer living outside of Paris. The prize of this collection was a 1902 Pathé cylinder of the serenade from Gounod’s Faust sung by Léon Melchissédec, the earliest-born French baritone to make records. I must admit that as a collector, acquiring these cylinders gave me a thrill, but it was terribly frustrating not to be able to hear them as I didn’t own cylinder playing equipment. I knew that they should not be played on an old windup horn machine, but I had no idea how to go about finding an electrical player. Michael Gunrem introduced me to a young German collector named Christian Zwarg who had built himself a simple electrical cylinder playback machine with a conventional phono cartridge, and who was enthusiastically making preservation transfers of cylinders held in private collections. He kindly sent me some of his excellent transfers, and we began a long-term correspondence that has continued until the present day. I finally found someone here in the States who was willing to build me an electrical cylinder machine using a tangential tracking system, and I began making rudimentary transfers of the cylinders I now owned.

The project evolved when my partner Scott Kessler and I struck up a friendship with Victor Girard, the coauthor with Harold Barnes of “Vertical Cut Cylinders and Discs” published by the British Institute of Recorded Sound. We told him of our plans to launch our reissue label, and he immediately suggested several projects devoted to great French singers of the past, offering to write our booklet essays. He also gave us about fifty French Pathé cylinders which he had collected during the 1950s, including four examples of the great nineteenth-century baritone Jean Lassalle. From that time forward, collecting records of French singers has become a passion for me, and they now represent the largest part of my record collection. Over the years, I have continued collecting cylinders in a modest fashion as well as following in Christian Zwarg’s path of preserving cylinders held in other collections.

This set derives not only from cylinders that have, over the years, passed through our hands, but also from the tremendous contributions of other collectors and institutions who have made available to us excellent transfers of cylinders in their collections. I would like to acknowledge especially the assistance of the late Richard Warren, former curator of Yale University’s archive of historic sound recordings, and Henri Chamoux for providing many digital transfers that have given us the opportunity to offer far more examples of these important singers than we could ever have envisioned. Additionally, I wish to offer my personal thanks to Christian Zwarg, whose assistance in almost every aspect of the project has been indispensable, and to Luc Bourrousse, whose exhaustive primary research into the careers of these singers has brought them so clearly into focus.

Bourrousse’s comprehensive essay for our set opens with a biographical sketch of the greatest of all nineteenth-century French baritones, Jean-Baptiste Faure, 1830-1914. During his great career, he created many important roles including Nélusko in Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine, Rodrigue in Verdi’s Don Carlos, and Thomas’s Hamlet. Luc Bourrousse has included J. B. Faure in his essay because of the formative influence he had on the baritones featured in this compilation. But there is another reason: over the past fifty years, transfers of two early brown wax cylinders of unidentified baritones have been issued on LP and CD with the attribution of the great Faure. Both of these cylinders were likely recorded by small recording companies operating in Paris at the turn of the century with no evidence that Faure is the voice singing on either of them. In fact, it is highly doubtful that either of these cylinders is sung by him, but we have included both of them as an appendix for all to hear. The cylinder containing the extract from La favorite is housed at Yale University’s Historic Sound Recordings and was transferred by me in 2004. The whereabouts of the “Cantique de Noël” cylinder is at this time unknown, and it comes from a primitive transfer made on an acoustic cylinder machine recorded by a microphone placed in front of the horn.

Most of the recordings in this compendium were made by the Pathé company in Paris between 1899 and 1909, and our booklet documentation would be incomplete without a brief overview of its procedures for manufacturing and marketing their recordings. Pathé began offering recordings for sale on brown wax cylinders in 1897. These were of the standard size as prescribed by Thomas Edison, measuring two inches in diameter and four inches in length, recorded at a nominal speed of 120 rpm. The great impediment in cylinder production for the commercial market was that no method for mass-producing cylinders had yet been developed. Each cylinder had to be individually recorded with the performer repeating the selection until a sufficient number of cylinders had been made. Additional copies were often made by using a mechanical pantographic system, but at best, only small quantities of each selection could be produced.

It was at this time that the competitive gramophone, which recorded on discs, began gaining ground over the cylinder, particularly because discs could be pressed from a master in seemingly limitless quantities. At this point, however, the cylinder was capable of producing superior sound to primitive gramophone discs, and Pathé tenaciously clung to it as did Edison on the other side of the Atlantic. CD one opens with two different recordings of Léon Melchissédec singing the drum major’s aria from Le caïd: the first on a Gramophone Company disc, and the second on a Pathé cylinder unaccountably sung without accompaniment. Both recordings are extremely primitive but sound very different: the gramophone disc is noisy with the voice rather submerged, while the cylinder has less background noise and more vocal presence. Incidentally, this 1899 disc was Melchissédec’s only Gramophone Company recording, while the Pathé cylinder of the same selection is just one of many that he recorded for the company in 1899, but sadly the only one to have come to light.

In 1902, Edison developed a method of molding master cylinders so that they could be perfectly replicated, using a new formulation of wax, which was black rather than the brown color of previous cylinders. Pathé quickly followed suit also switching to a black wax but only when its stock of brown wax had been exhausted. But this is where the similarity between the companies ended. Edison’s cylinders were directly molded from his master cylinder recordings. On the other hand, Pathé devised a complicated system that led to the production of inferior sounding records for the next quarter century. In a nutshell, here is how it worked. Each recording was assigned a master number and recorded at 160 rpm on a large wax cylinder measuring twelve and a half centimeters in diameter and twenty-two centimeters in length. Large cylinders were used in order to increase the groove velocity of the cutting stylus and thereby capture a greater degree of high frequency information. Next, each master cylinder was then pantographically rerecorded onto a standard sized cylinder inscribed with the same matrix number and also a secondary number that related to that particular pantographic transfer. This small cylinder became in essence the production master which was molded and replicated for sale. Pathé’s system produced unreliable results ranging from surprisingly excellent to unimaginably poor, seemingly with no concern for quality control. Master cylinders were often transferred more than once in order to produce additional production masters, with a new transfer number assigned to each subsequent transfer. In fact, two cylinders of the same recording can sound completely different, and occasionally come from alternative takes.