Goldsand’s pianism was characterized by a remarkable range in tone color, an unusual degree of interpretative freedom, and a complete command of the instrument. At times he would follow the letter of the text scrupulously, while at others he would adopt a seemingly willful disregard for the composer. In either case, Robert Goldsand’s recordings demand attention and are worthy additions to any piano-recording collection.

Goldsand made few commercial recordings, yet surreptitiously-recorded tapes of Goldsand recitals (mid 1960s) exist and have been circulated among collectors. Beginning earlier (the mid-1950s), Goldsand arranged for many of his New York recitals to be professionally taped for his own retention. These remained in his possession until his death in 1991 and nearly 100 open-reel tapes in deplorable condition were donated to the International Piano Archives at the University of Maryland. A massive conservation project was expertly and painstakingly accomplished by Seth B. Winner Sound Studios, Inc. resulting in a new cache of recordings.

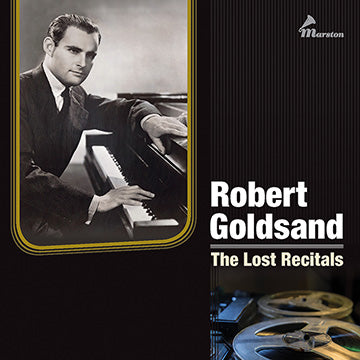

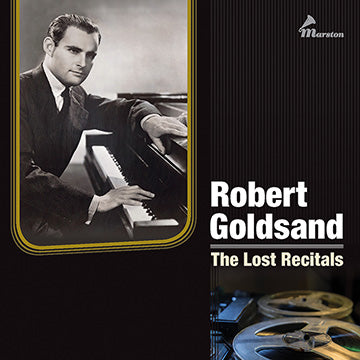

After auditioning more than two dozen Goldsand recitals from the preserved and digitized tapes, the performances presented here were chosen to represent him at the height of his powers. Notes are by IPAM Curator Donald Manildi. This three-CD Marston release marks the first–and long overdue–representation of Robert Goldsand's playing on compact disc. It offers performances from 1956 through 1977.

CD 1 (73:08) | ||

30 September 1977, New York City | ||

CLEMENTI: | ||

| Sonata in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 25, No. 5 | ||

| 1. | I. Allegro con espressione | 8:11 |

| 2. | II. Lento e patetico | 3:41 |

| 3. | III. Presto | 4:30 |

GUARNIERI: | ||

| Sonatina No. 3, “In the G Clef” | ||

| 4. | I. Allegro | 3:53 |

| 5. | II. Con tenerezza | 2:29 |

| 6. | III. Two-part Fugue: Ben ritmico | 2:16 |

23 July 1975, Syracuse, New York | ||

CHOPIN: | ||

| 7. | Nouvelle Etude No. 1 in F Minor | 2:36 |

| 8. | Etude in F Minor, Op. 25, No. 2 | 1:35 |

| 9. | Etude in F, Op. 10, No. 8 | 2:34 |

| 10. | Etude in F, Op. 25, No. 3 | 1:56 |

| 11. | Etude in A Minor, Op. 10, No. 2 | 1:29 |

| 12. | Etude in A Minor, Op. 25, No. 11, “Winter Wind” | 4:27 |

| 13. | Etude in E, Op. 10, No. 3 | 4:59 |

| 14. | Etude in G-Sharp Minor, Op. 25, No. 6, “Thirds” | 2:12 |

| 15. | Nouvelle Etude No. 2 in A-Flat | 2:40 |

| 16. | Etude in C Minor, Op. 10, No. 12, “Revolutionary” | 3:25 |

30 September 1977, New York City | ||

CHOPIN: | ||

| 17. | Etude in G-Flat, Op. 10, No. 5, “Black Keys” | 1:54 |

| 18. | Etude in G-Flat, Op. 25, No. 9, “Butterfly” | 1:05 |

CHOPIN-GODOWSKY: | ||

| 19. | “Badinage” (Op. 10, No. 5 and Op. 25, No. 9 combined) | 1:41 |

CHOPIN: | ||

| 20. | Berceuse in D-Flat, Op. 57 | 5:22 |

| 21. | Waltz in A-Flat, Op. 42 | 3:53 |

23 July 1975, Syracuse, New York | ||

CHOPIN-ROSENTHAL: | ||

| 22. | Waltz in D-Flat, Op. 64, No. 1, “Minute” | 2:20 |

MOZART: | ||

| 23. | Gigue in G, K.574 | 1:43 |

27 November 1978, New York City | ||

SCHUBERT-GANZ: | ||

| 24. | Ballet Music from “Rosamunde” | 2:18 |

CD 2 (76:31) | ||

Circa 1960, London, UK | ||

MOZART: | ||

| Sonata No. 17 in D, K.576 | ||

| 1. | I. Allegro | 5:23 |

| 2. | II. Adagio | 5:52 |

| 3. | III. Allegretto | 4:22 |

BEETHOVEN: | ||

| Sonata No. 24 in F-Sharp, Op. 78 | ||

| 4. | I. Adagio cantabile; Allegro ma non troppo | 7:13 |

| 5. | II. Allegro vivace | 2:53 |

17 October 1956, New York City | ||

SCHUMANN: | ||

| 6. | Novelette in F-Sharp Minor, Op. 21, No. 8 (abridged) | 6:32 |

| 7. | Toccata in C, Op. 7 | 5:40 |

Circa 1952, Concert Hall Society LP (CHS 1149) | ||

RACHMANINOFF: | ||

| 8. | Variations on a Theme of Chopin, Op. 22 (abridged) | 19:02 |

30 April 1963, New York City | ||

RACHMANINOFF: | ||

| 9. | Prelude in E-Flat Minor, Op. 23, No. 9 | 2:07 |

| 10. | Prelude in B-Flat, Op. 23, No. 2 | 3:52 |

| 11. | Prelude in G, Op. 32, No. 5 | 2:54 |

| 12. | Prelude in G Minor, Op. 23, No. 5 | 4:18 |

| 13. | Prelude in B Minor, Op. 32, No. 10 | 6:22 |

CD 3 (71:15) | ||

24 January 1956, New York City | ||

LISZT: | ||

| Six Etudes After Paganini, S. 141 | ||

| 1. | No. 1 in G Minor, “Tremolo” | 4:43 |

| 2. | No. 2 in E-Flat, “Capriccioso” | 5:24 |

| 3. | No. 3 in G-Sharp Minor, “La Campanella” | 4:38 |

| 4. | No. 5 in E, “La Chasse” | 3:01 |

| 5. | No. 4 in E, “Arpeggio” | 2:10 |

| 6. | No. 6 in A Minor, “Theme and Variations” | 6:46 |

Unknown Date and Location | ||

CHOPIN: | ||

| 7. | Polonaise in C Minor, Op. 40, No. 2 | 6:05 |

| 8. | Variations on Mozart’s “La ci darem la mano,” Op. 2 | 13:02 |

PROKOFIEV: | ||

| 9. | Prelude in C, Op. 12, No. 7 | 2:23 |

| 10. | March in F Minor, Op. 12, No. 1 | 1:54 |

ALBENIZ: | ||

| 11. | Triana, No. 6 from “Iberia” | 4:50 |

24 January 1956, New York City | ||

HANDEL: | ||

| 12. | Suite No. 2 in F: Second Movement, Adagio | 3:27 |

Circa 1964, Desto LP (D-200) | ||

GODOWSKY: | ||

| 13. | Symphonic Metamorphosis on Themes from “Die Fledermaus” by Johann Strauss Jr. | 8:30 |

9 December 1960, New York City | ||

BACH-HESS: | ||

| 14. | Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, from Cantata No. 147 | 4:24 |

Producers: Ward Marston and Scott Kessler

Associate Producer: Donald Manildi

Archival Mastering from Original Tapes: Seth B. Winner Sound Studios

Final Mastering: Ward Marston and J. Richard Harris

Photos: International Piano Archives at Maryland (IPAM, University of Maryland, College Park)

Booklet Coordinator: Mark S. Stehle

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Booklet Notes: Donald Manildi

Engineer’s Note: Seth B. Winner

This project has been fully funded by an anonymous donor.

Marston would like to thank the International Piano Archives at Maryland (University of Maryland, College Park) for the use of recordings from their collection.

ROBERT GOLDSAND: THE LOST RECITALS

©2022 by Donald Manildi

Curator, International Piano Archives at Maryland (IPAM)

Although fortune did not favor him with international stardom, Robert Goldsand nonetheless established an enviable and in many ways unique position among twentieth-century pianists. In a career that spanned more than six decades, he garnered a loyal following through his frequent concert appearances, and his name still resonates with many connoisseurs of fine pianism. Goldsand’s official recorded legacy, however, is far from extensive and as we shall see, a fortuitous set of circumstances has brought about the preservation of many of his public performances. With two exceptions, the contents of these CDs are taken from private tapes of Goldsand recitals and broadcasts between 1956 and 1978.

Born in Vienna on the 17th of March, 1911, Goldsand studied violin before the age of six but quickly revealed a much greater aptitude for the piano. He easily passed the entrance examinations of the Vienna Academy of Music, where he was placed under the tutelage of Alexander Manhardt. After four years he made his recital debut at age ten and became a pupil of Hedwig Kanner-Rosenthal, wife of Moriz Rosenthal. Goldsand later had lessons with Rosenthal himself, and some sources refer to a brief period of study with another eminent Liszt pupil, Emil Sauer. Concert tours soon followed, first in Austria, then in the Balkan states, Germany, and the Scandinavian countries. In 1923, Goldsand made his orchestral debut with the Berlin Philharmonic. With Vienna and Berlin being major musical centers where all the leading virtuosos of the day performed regularly, Goldsand witnessed and absorbed the level of individuality that these pianists represented.

On 21 March 1927, he played for the first time in America at New York’s Town Hall, and two weeks later he appeared as soloist with the New York Symphony in Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasy. For the next eight years he was a frequent visitor to the US, and during the 1931 season he presented three varied programs that filled Carnegie Hall to capacity.

Between 1935 and 1940, Goldsand withdrew from the concert platform. In an article for Musical America magazine, Goldsand said:

I was constantly playing, traveling about and fulfilling engagements. I felt it was necessary to rest and to improve myself artistically. Fortunately, at the time I could afford to do so. For five years I retired to a little town in the Alps, far away from turmoil and activity, and I concentrated upon improving my work. No one can continue constantly, from boyhood to maturity, appearing in concert without feeling a strain and suffering artistically. During this ‘retirement’ period I went over my technique, interpretation, repertoire, and I increased my knowledge of music. When I returned, I had a broader viewpoint and was refreshed artistically.

The Nazi Anschluss of Austria in 1938 compelled Goldsand’s return to the US, where he settled and became a citizen. His annual New York recitals generated a loyal following over the next forty years, and he fulfilled engagements throughout America along with occasional bookings in Europe—although he did not return to his native Austria. Goldsand accepted a teaching position at the Cincinnati College-Conservatory in 1949 and two years later at the Manhattan School of Music, then located on East 105th Street. Goldsand commuted by train from his home in Danbury, Connecticut that he shared with his wife Mimi and two German Shepherd dogs. Beginning in 1954, he routinely visited Miami University in Oxford, Ohio during the summer, giving workshops for aspiring students and offering a different recital program each year. In 1956 the university conferred upon him an honorary Doctor of Letters degree.

Among pianists active in the twentieth century, few could boast of a repertoire as varied and extensive as Goldsand’s. There were seemingly no areas of the piano literature that did not interest him, and his choice of material for his recitals was fueled by an insatiable curiosity to explore untrammeled paths as well as all the standard masterworks. During the Second World War, Goldsand presented a complete Beethoven Sonata cycle to New York audiences. In 1949, in observance of the centenary of Chopin’s death, he offered a series of six all-Chopin programs that encompassed both familiar and neglected areas of the Chopin repertoire. Goldsand played commemorative all-Schumann and all-Rachmaninoff recitals in 1956 and 1963 respectively, and on several occasions (beginning as early as 1932) he prepared a three-recital panorama called “Three Centuries of Piano Music” containing representative works from the classical, romantic, and modern eras.

An examination of his programs over the years also reveals such esoteric items as Godowsky’s Passacaglia, Reger’s Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Telemann, and the Sonata No. 4 of Miaskovsky. From the earlier branches of the literature, Goldsand programmed the Goldberg Variations and most of the French Suites and Partitas of J.S. Bach as well as works of Handel, Scarlatti, and C.P.E. Bach. Among the American composers favored by Goldsand we find Griffes (Sonata), Barber (Sonata), Copland, Giannini, Farwell, Gershwin, Earl George, Marion Bauer, Halsey Stevens, Theodore Chanler, Charles Haubiel, and George Walker. Major twentieth-century masters such as Szymanowski, Bartók, Berg, Schoenberg, Hindemith, and Stravinsky also appeared regularly on his recitals. For his orchestral engagements, Goldsand had at his fingertips some thirty-five concerti, any of which he was prepared to play at a moment’s notice.

In a 1946 interview, Goldsand explained:

I have made it a custom from my childhood days to play one work new to my programs at every concert. This rule I have followed in general throughout my career. By the time I was twenty-one, continually performing works new to my repertoire, I had a very large list of piano music in my fingers.

When asked about his impressive musical memory, Goldsand said:

The fingers have their own memory, the ear its own, and the eye too. I have the kind of visual memory that gives me, as I play, the pages in front of me, and so mentally I turn the pages! I think the reason I remember a large repertoire is that I simply like all of it so much that I never tire of studying, playing, and adding to it!

Robert Goldsand’s commercially-issued recordings are far fewer than might be expected. His earliest discs (78 rpm) date from just after the Second World War, and include albums of Chopin, Schumann, and Rachmaninoff, for the small, short-lived International label and for American Decca. At the start of the LP era and into the 1950s, he made a series of ten discs for Concert Hall Society. Works of Chopin predominate, including the complete Etudes, the three early sets of Variations, and the first-ever recording of his youthful C Minor Sonata, Op. 4. The additional CHS releases are devoted to Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Rachmaninoff, and Paganini-Liszt. After a brief hiatus, Goldsand made his only concerto recordings (Beethoven Nos. 1 and 2) for Urania, partnered by conductor Carl Bamberger and the Frankfurt Opera Orchestra. Completing his discography is a two-LP set on the Desto label, issued in 1964 and containing a miscellany of standard items by Mozart, Beethoven, Chopin, Ravel, Prokofiev, and others. The era of compact discs saw no Goldsand material whatsoever, and the present collection is his first representation (long overdue) in that medium.

As the performances included here clearly reveal, Goldsand, like many pianists trained in an earlier era, treated the printed score, in certain instances, with an unusual degree of freedom. For example, in the Schumann Novelette No. 8, he presents only the first half of the work, omitting entirely the section marked “Fortsetzung und Schluss” (continuation and conclusion). However, this novelette is actually two pieces in one, the loosely attached second part having no direct relationship to the first, and Goldsand obviously considered the opening section to be sufficient in itself. In the second of the six Paganini-Liszt Etudes he makes numerous small emendations to the text; in one pyrotechnical flourish (at 3:44 to 3:54) he extends the keyboard range in both directions beyond Liszt’s original. And in the sixth etude, Goldsand adds unwritten repeats to the second halves of most of the variations, he omits variation 8, reverses the order of 9 and 10, and rewrites the ending to provide additional bravura.

For Chopin’s “La ci darem” Variations, Goldsand removes a twenty-two-measure section from the lengthy introduction, and in the Rachmaninoff Prelude in B-Flat, he excises eight measures of repetitive material which (it could be argued) tend to impede the flow of the music. In Rachmaninoff’s Variations on a Theme of Chopin (the familiar C Minor Prelude), Goldsand offers an abridged version that eliminates variations 12, 18, 19, and 20. He then cuts the first twenty-four measures of variation 21 and jettisons substantial portions of 22. (A precedent can be found in accounts of Rachmaninoff himself playing his later Variations on a Theme of Corelli). Similarly, the Strauss-Godowsky Fledermaus is somewhat shortened, with Goldsand favoring options authorized by Godowsky in his original edition.

These modifications were all carefully considered, and far from being arbitrary or willful they actually enhance the spirit of the music and are totally in keeping with performance practices of the Romantic period. Elsewhere, Goldsand is much more conservative. For instance, in his approach to the Clementi, Mozart, and Beethoven Sonatas, he follows the letter of the text scrupulously while imbuing these scores with a tasteful, stylistically apropos degree of dynamic and agogic nuance.

The comprehensiveness of Goldsand’s repertoire was matched by the range and versatility of his pianistic command. He could exploit the tonal spectrum of the instrument to an extraordinary degree, and from the performances included here we can witness the elegance and polish of Mozart’s D Major Sonata, the warmth and serenity of the Rachmaninoff Prelude in G Major, and the truly apocalyptic conclusion of the sixth Paganini-Liszt Etude. The group of Chopin Etudes, drawn from all three collections (Op. 10, Op. 25, and the Trois Nouvelles), was carefully assembled by Goldsand for maximum contrast, and this particular sequence was a recurring feature of his recitals for many years. In the challenging Johann Strauss-Godowsky Fledermaus Paraphrase, Goldsand easily untangles the luxuriant figuration and contrapuntal complexities of that terpsichorean phantasmagoria.

In a review of one of Goldsand’s New York recitals, Harold C. Schonberg, chief music critic of the New York Times, commented:

His interpretations were fresh, subtle and when needed, heroic. Color and style abounded. That, and an extremely wide dynamic palette, including a triple pianissimo that really sounded. Mr. Goldsand can supply a brand of playing that reaches back into an evocation of the great group of pianistic heroes who flourished at the turn of the [twentieth] century.

An especially succinct summation of Goldsand’s playing is the following from critic Harris Goldsmith:

Goldsand’s artistic make-up is one of paradoxes. He can be the reverent scholar and blatant iconoclast; he embraces something of the lavish romantic and the stringent classicist; the steel-point engraver and the exotic colorist. In any case one can always be reasonably sure that, whether for better or worse, his reading of a given work is going to be different from everyone else’s. Disagree or not, one must admire his creative vitality and technical freedom. Not many players still have Goldsand’s sort of pianistic spontaneity.

In the many years he spent as a teacher, Goldsand instructed a wide variety of young pianists who gratefully acknowledged his coaching. One of them, Sura Kim, recalls that “there was real camaraderie among his students, and he remained in touch over the years.” She also remembers that Goldsand advocated the use of a dummy piano (silent keyboard, with adjustable action) for practice purposes. (Moriz Rosenthal did the same, and Harold Bauer, Shura Cherkassky, and Claudio Arrau were among the famous pianists who also made use of one.) Goldsand’s weekly lessons, according to Sura Kim, were taught in both private and master class settings. Another former pupil, Mahbubeh Stave, recalls Goldsand as “kind, patient and encouraging. He approached his students like a doctor, tailoring his teaching to their individual personalities and capabilities. Also, he was more interested in interpretation than in technical exercises. He assumed that the student would take care of mechanics at home.”

As described earlier, Goldsand’s official discography is limited and is far from properly representative. Fortunately, beginning in the mid-1950s he arranged for many of his New York recitals to be professionally taped for his own retention. Furthermore, by the mid-1960s surreptitious recording of concerts by audience members was underway, and tapes of many Goldsand recitals now exist thanks to the foresight of those enthusiasts who preserved them for posterity. Some of the latter performances have circulated among collectors, but Goldsand’s own private recordings remained in his possession until his death in 1991. It was not until the settlement of his estate some nine years later that the extent of these recordings became evident. A neighbor and friend of Mr. and Mrs. Goldsand in Danbury discovered nearly 100 open-reel tapes stored in the pianist’s studio under less-than-ideal conditions. In fact, the studio had begun to collapse from disrepair, and some of the tapes were afflicted with mold, mildew, and other problems. Through sheer good fortune, the neighbor was aware of the International Piano Archives at the University of Maryland and contacted IPAM to offer a donation of the tapes—which was immediately accepted. It was soon discovered that only some of the recordings were properly identified. Many lacked dates, venues, and/or program information. However, careful research has unearthed much of the missing detail. The accompanying track listing includes all available documentation.

Upon the arrival of the tapes there were major issues of preservation and restoration to be dealt with, and audio engineer Seth B. Winner was engaged to undertake a massive project of not only handling the problematic condition of the tapes, but also transferring their contents to the digital domain with maximum quality. (Mr. Winner gives a detailed account of his work in the Engineer’s Note that follows.) Then, after auditioning more than two dozen Goldsand recitals from the preserved and digitized tapes, the performances presented here were chosen to represent him at the height of his powers.

When Harold Schonberg said in 1962 that “Mr. Goldsand is a remarkable pianist who, for one reason or another, has never had his full due,” that fact remained true into the 1980s and beyond. Throughout his long career, Goldsand steadfastly pursued his own brand of pianism, always giving his audiences an enticing mixture of fascination and satisfaction. Unlike some of his colleagues, he pursued his goals without any extra-musical dalliances or craving for the spotlight. It is hoped that the performances included herewith will bring renewed awareness of one of the past century’s unique pianistic practitioners.

ENGINEER’S NOTE

©2022 by Seth B. Winner

President, Seth B. Winner Sound Studios, Inc.

In 2019, Mr. Manildi approached me to conserve and digitally preserve the tapes from Robert Goldsand’s private collection that had been damaged due to neglect during storage. Upon their arrival, I had to deal with a severe case of mold damage that had affected the integrity of each reel; they had been sealed in plastic bags in order to prevent contamination to the environment. In fact, all the cardboard boxes in which they were housed were completely destroyed as a result.

Each tape was then removed from the plastic bags and vacuumed clean on both sides before being placed on a reel-to-reel machine. Cleaning involved slow winding each reel at 15ips in both directions several times, with the vacuum cleaner always present to catch the residual mold that had caked up around each reel. After each pass in each direction, the entire tape transport was cleaned with Q-Tips and isopropyl alcohol. Finally, after a sufficient amount of the debris had been removed, an application of alcohol was used to remove the final level of contamination from the surface of each reel of tape.

Next, the cleaned reels were leadered and tight-wound onto slotless plastic reels. The acetate-base tapes were wound oxide-out in order to undo the edge curl and cupping damage that is common with tapes of that type. All the conserved tapes were placed in new boxes and left alone for a period of three months.

After the proscribed period, I began playing back each tape in order to create preserved digital audio files for audition purposes. The mylar-based tapes reacted very well during playback; the acetate-based reels posed some problems due to their original storage conditions. As a result, these tapes were a challenge to transfer; some of them took several hours to retrieve. After careful manipulation of the tape path on two different machines, as well as using pressure pads, I was able to retrieve nearly all the recorded material from the tapes that were initially conserved. A second group of damaged reels that required the same preparation techniques was delivered early in 2022.

After the final selections were made, I worked to restore each performance intended for the present compilation. Some were relatively clean and required little if any processing. Besides the usual equalization and level corrections, others required pitch stability software as well as hum removal. I was able to remedy the pitch and hum problems with plugins from CEDAR, known as RESPEED and DEBUZZ. Of course, RETOUCH was also used to remove the various extraneous noises that were usually present in these live recordings such as thumps, knocks, squeaks and subway noises which were evident in the Carnegie Hall concerts.

Despite all these pitfalls the results, I believe, give full evidence of the artistry of one of the great but nearly forgotten pianists of the twentieth century.

Robert Goldsand ‘The Lost Recitals’ [pdf]

Marston's glowing three-disc tribute remembers, to quote Donald Manildi and Seth Winner’s no less glowing notes, ‘one of the great but nearly forgotten pianists of the 20th century’...

Wherever you listen you will hear a flat contradiction of an opinion included in that august publication The Record Guide (Edward Sackville-West and Desmond Shawe-Taylor) that Goldsand ‘s adept at giving you precisely what is on the page; but in no case does he give much more’. These words were written about studio recordings whereas the present issue is of live performances, and

the difference is immeasurable.

—Bryce Morrison, International Piano, November, 2023

Boxes Column: Robert Goldsand, Marston [pdf]

Marston’s catalogue of freshly discovered, or rediscovered, musicians from the past is impressive by any standards, but with a 3-cd set devoted to (mostly) live recitals featuring the Austrian-American pianist Robert Goldsand (1911-1991), a Moritz Rosenthal-pupil who launched his performing career at the age of 10, he scores even higher than usual...

It’s an enticing introduction to a musician’s musician, and the transfers (by Seth Winner) are, for the most part, first-rate. So are Donald Manildi’s notes.

—Rob Cowan, Gramophone, December, 2023