His musically rich and varied career in Europe ended abruptly in 1937 when his outspoken opposition to Hitler’s regime led to his pursuit by the Gestapo and eventual escape and exile. Until then, he had given highly praised performances, not only of the Wagnerian roles for which he is chiefly remembered today, but of Mozart, Gluck, a great deal of Verdi and other Italian and French operas, as well as of contemporary works and even Russian repertoire.

Janssen’s Lieder singing on record has left memorable interpretations of songs by Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Wolf, and Strauss which are still highly prized today.

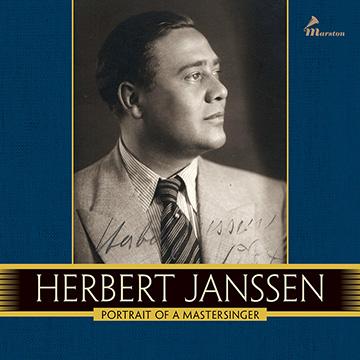

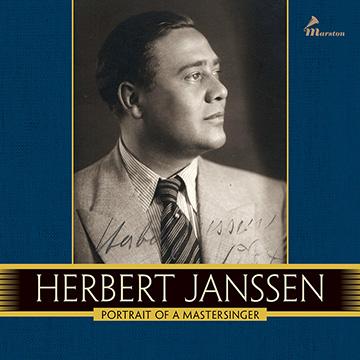

The present collection includes all his surviving pre-war studio recordings of opera and operetta (except for the 1930 Columbia Tannhäuser); all of Janssen’s surviving 78 rpm Lieder recordings, including several previously unpublished items; and rare broadcast material that appears here together for the first time. The set includes liner notes by Iain Miller and Michael Aspinall, as well as a large selection of rare photos. As a portrait of one of the greatest baritones on records, this six-CD set of Herbert Janssen is the most complete yet to appear.

CD 1 (72:55) | ||

| I. Recordings of Opera and Operetta | ||

| 1923-1930 | ||

| 1. | RIGOLETTO: Tutte le feste al tempio … Piangi, fanciulla (Verdi) | 4:22 |

| Lotte Schöne, soprano Berlin State Opera Orchestra, conducted by Fritz Zweig | ||

| 11 November 1927, Berlin; Gramophone Company; CWR1341-1 (DB1127) | ||

| 2. | MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Ora a noi. Sedete qui. (Hört mich an, und setzt Euch her) (Puccini) | 8:47 |

| with Margherita Perras, soprano orchestra conducted by Selmar Meyrowitz | ||

| 24 September 1929, Berlin; Ultraphone; 30266 and 30267 (F.213) | ||

| 3. | FAUST: O sainte médaille … Avant de quitter ces lieux (Da ich nun verlassen soll) (Gounod) | 3:53 |

| Berlin State Opera Orchestra, conducted by Fritz Zweig | ||

| 19 April 1928, Berlin; Gramophone Company; CLR4044-2 (Eh219) | ||

| 4. | FAUST: Écoute-moi bien, Marguerite (Höre mich jetzt an, Margarethe) (Gounod) | 4:18 |

| Berlin State Opera Orchestra, conducted by Fritz Zweig | ||

| 19 April 1928, Berlin; Gramophone Company; CLR4043-2 (Eh219) | ||

| 5. | DER WAFFENSCHMIED: Du läßt mich kalt von hinnen scheiden (Lortzing) | 2:36 |

| Berlin State Opera Orchestra, conducted by Fritz Zweig | ||

| 18 April 1928, Berlin; Gramophone Company; BLR4040-1 (EG898) | ||

| 6. | ZAR UND ZIMMERMANN: Sonst spielt’ ich mit Zepter (Lortzing) | 3:23 |

| Berlin State Opera Orchestra, conducted by Fritz Zweig | ||

| 19 April 1928, Berlin; Gramophone Company; BLR4045-2 (EG898) | ||

| 7. | TANNHÄUSER: Als du in kühnem Sange uns bestrittest (Wagner) | 3:13 |

| unidentified orchestra and conductor | ||

| December 1923, Berlin; Odeon; xxBo 8045-2 (AA 79413) | ||

| 8. | TANNHÄUSER: Wohl wußt’ ich hier sie im Gebet zu finden (Wagner) | 3:06 |

| unidentified orchestra and conductor | ||

| December 1923, Berlin; Odeon; xxBo 8046-1 (AA 79414) | ||

| 9. | TANNHÄUSER: Als du in kühnem Sange uns bestrittest (Wagner) | 6:44 |

| with Sigismund Pilinszky, tenor; Ivar Andrésen, bass; and minstrels Bayreuth Festival Orchestra, conducted by Karl Elmendorff | ||

| 23-26 August 1930, Bayreuth; English Columbia; WAX5698-3 and WAX5699-2 (LCX53) | ||

| 10. | TANNHÄUSER: Blick ich umher in diesem edlem Kreise (Wagner) | 4:28 |

| Bayreuth Festival Orchestra, conducted by Karl Elmendorff | ||

| 23-26 August 1930, Bayreuth; English Columbia; WAX 5705-1 (LCX56) | ||

| 11. | TANNHÄUSER: Wohl wußt’ ich hier sie im Gebet zu finden (Wagner) | 4:12 |

| orchestra conducted by Selmar Meyrowitz | ||

| 13 December 1929, Berlin; Ultraphone; 30384 (EP.279) | ||

| 12. | TANNHÄUSER: Wie Todesahnung Dämmrung deckt die Lande ... O du mein holder Abendstern (Wagner) | 4:19 |

| orchestra conducted by Selmar Meyrowitz | ||

| 13 December 1929, Berlin; Ultraphone; 30385 (EP.279) | ||

| 13. | GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG: Welches Unholds List (Act 2, Finale) (Wagner) | 12:41 |

| with Nanny Larsén-Todsen, soprano and Ivar Andrésen, bass Berlin State Opera Orchestra, conducted by Leo Blech | ||

| 19 April 1928, Berlin; Gramophone Company; CLR3975-1, 3976-1, and 3977-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 14. | DIE DREI MUSKETIERE: Ich liebe dich (Fitch-Lowe, arranged Benatzky1) | 3:27 |

| orchestra of the Grosses Schauspielhaus, conducted by Ernst Hauke | ||

| 7 October 1929, Berlin; Gramophone Company; BLR5673-1 (EG1557) | ||

| 15. | DIE DREI MUSKETIERE: Du schmeichelst in mein Herz dich ein (Benatzky) | 3:25 |

| with Göta Ljungberg, soprano orchestra of the Grosses Schauspielhaus, conducted by Ernst Hauke | ||

| 7 October 1929, Berlin; Gramophone Company; BLR5674-2 (EG1556) | ||

CD 2 (79:42) | ||

| II. Recordings made for the Hugo Wolf Society | ||

| Gramophone Company, Berlin, 1932-1935 | ||

| 29 September 1932 | ||

| Coenraad V. Bos, piano | ||

| 1. | Harfenspieler I: Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:42 |

| 2D1155-2 (DB1825) | ||

| 2. | Harfenspieler II: An die Türen will ich schleichen from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:05 |

| 2D1152-2 (DB1825) | ||

| 3. | Harfenspieler III: Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:13 |

| 2D1153-1 (DB1826) | ||

| 4. | Anakreons Grab from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:30 |

| 2D1154-1 (DB1826) | ||

| 5. | Cophtisches Lied II: Geh! Gehorche meinen Winken from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:04 |

| 2D1154-1 (DB1826) | ||

| 22 September 1934 | ||

| Coenraad V. Bos, piano | ||

| 6. | Denk’ es, o Seele! from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:23 |

| 2RA101-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 7. | Gebet from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:16 |

| 2RA102-2 (DB2705) | ||

| 8. | Auf ein altes Bild from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:17 |

| 2RA102-2 (DB2705) | ||

| 9. | An die Geliebte from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:23 |

| 2RA103-2 (DB2705) | ||

| 10. | Wächterlied auf der Wartburg from SECHS GEDICHTE VON SCHEFFEL, MÖRIKE, GOETHE, UND KERNER (Wolf) | 4:05 |

| 2RA104-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 4 November 1935 | ||

| Michael Raucheisen, piano | ||

| 11. | Verborgenheit from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:53 |

| 2RA858-1 (DB2706) | ||

| 12. | Biterolf im Lager von Akkon from SECHS GEDICHTE VON SCHEFFEL, MÖRIKE, GOETHE, UND KERNER (Wolf) | 2:44 |

| 2RA859-1 (DB2704) | ||

| 13. | Seufzer from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:57 |

| 2RA859-1 (DB2704) | ||

| 14. | Denk’ es, o Seele! from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:42 |

| 2RA860-1 (DB2706) | ||

| 15. | Bei einer Trauung from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:50 |

| 2RA860-1 (DB2706) | ||

| III. Excerpts from Live Performances | ||

| Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London, 1936 and 1937 | ||

| 16. | GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG: Heil! Heil! Willkommen … Brünnhild, die hehrste Frau (Act 2, Scene 4) (Wagner) | 5:34 |

| 14 May 1936, London Philharmonic, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham | ||

| 17. | GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG: Welches Unholds List (Act 2, finale) (Wagner) | 14:16 |

| with Frida Leider, soprano and Ludwig Weber, bass | ||

| 14 May 1936, London Philharmonic, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham | ||

| 18. | DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER: Die Frist ist um (Wagner) | 10:36 |

| 11 June 1937, London Philharmonic, conducted by Fritz Reiner | ||

| 19. | DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER: Wie aus der Ferne (Wagner) | 7:10 |

| with Kirsten Flagstad, soprano | ||

| 11 June 1937, London Philharmonic, conducted by Fritz Reiner | ||

CD 3 (68:07) | ||

| IV. Selected Lieder by Johannes Brahms, Franz Schubert, and Robert Schumann | ||

| Gramophone Company, Berlin and London, 1936–1938 | ||

| 1. | Wie bist du, meine Königin, Op. 32, No. 9 (Brahms) | 3:44 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 15 June 1937, London; 2EA4975-1 (DB3941) | ||

| 2. | Nicht mehr zu dir zu gehen, Op. 32, No. 2 (Brahms) | 2:26 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 15 June 1937, London; 2EA4974-1 (DB3941) | ||

| 3. | Minnelied, Op. 71, No. 5 (Brahms) | 2:08 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 15 June 1937, London; 2EA4974-1 (DB3941) | ||

| 4. | Auf dem Kirchhofe, Op. 105, No. 4 (Brahms) | 2:30 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 15 June 1937, London; 2EA4976-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 5. | Ständchen (Leise flehen meine Lieder), No. 4 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 3:56 |

| Michael Raucheisen, piano | ||

| 10 November 1936, Berlin; 2RA1585-1 (DB3024) | ||

| 6. | Der Doppelgänger, No. 13 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 3:57 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 29 August 1937, Berlin; 2RA2197-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 7. | Ganymed, D.544 (Schubert) | 4:16 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 22 March 1938, London; 2EA6153-2 (HMB157) | ||

| 8. | Der Wegweiser, No. 20 from WINTERREISE, D.911 (Schubert) | 3:57 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 22 March 1938, London; 2EA6154-1 (DB3496) | ||

| 9. | Das Wirtshaus, No. 21 from WINTERREISE, D.911 (Schubert) | 4:03 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 22 March 1938, London; 2EA6155-1 (DB3496) | ||

| 10. | Romanze (Der Vollmond strahlt), No. 3 from ROSAMUNDE, D.797 (Schubert) | 2:51 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 22 March 1938, London; 2EA6156-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 11. | Kriegers Ahnung, No. 2 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 4:30 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 29 August 1937, Berlin; 2RA2199-2 (HMB157) | ||

| 12. | Ständchen (Leise flehen meine Lieder), No. 4 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 4:16 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 16 November 1938, London; 2EA7121-1T (DB5797) | ||

| 13. | Der Atlas, No. 8 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 2:00 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 29 August 1937, Berlin; 0RA2200-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 14. | Ihr Bild, No. 9 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 3:17 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 29 August 1937, Berlin; 0RA2195-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 15. | Die Stadt, No. 11 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 2:58 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 29 August 1937, Berlin; 2RA2196-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 16. | Der Doppelgänger, No. 13 from SCHWANENGESANG, D.957 (Schubert) | 4:45 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 17 November 1938, London; 2EA7124-2 (DB5797) | ||

| 17. | Die Allmacht, D.852 (Schubert) | 4:25 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 17 November 1938, London; 2EA7127-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 18. | Die beiden Grenadiere, Op. 49, No. 1 (Schumann) | 3:41 |

| Michael Raucheisen, piano | ||

| 10 November 1936, Berlin; 2RA1586-2 (DB3024) | ||

| 19. | Widmung, No. 1 from MYRTHEN, Op. 25 (Schumann) | 2:10 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 10 June 1937, London; 0EA4955-2 (DA1569) | ||

| 20. | Die Lotosblume, No. 7 from MYRTHEN, Op. 25 (Schumann) | 2:15 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 10 June 1937, London; 0EA4965-1 (DA1569) | ||

CD 4 (52:25) | ||

| V. Selected Lieder by Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss | ||

| Gramophone Company, Berlin and London, 1936–1938 | ||

| 1. | Keine gleicht von allen Schönen from VIER GEDICHTE NACH HEINE, SHAKESPEARE, UND LORD BYRON (Wolf) | 2:19 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 17 November 1938, London; 2EA7125-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 2. | Sonne der Schlummerlosen, from VIER GEDICHTE NACH HEINE, SHAKESPEARE, UND LORD BYRON (Wolf) | 2:38 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 16 November 1938, London; 2EA7122-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 3. | Wo wird einst des Wandermüden, from VIER GEDICHTE NACH HEINE, SHAKESPEARE, UND LORD BYRON (Wolf) | 2:39 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 15 June 1937, London; 2EA4968-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 4. | Dereinst, dereinst, Gedanke, mein, from SPANISCHES LIEDERBUCH (Wolf) | 2:29 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 20 May 1937, London; 2EA4951-1 (DB3325) | ||

| 5. | Alle gingen, Herz, zu Ruh, from SPANISCHES LIEDERBUCH (Wolf) | 1:50 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 20 May 1937, London; 2EA4951-1 (DB3325) | ||

| 6. | Tief im Herzen trag’ ich Pein, from SPANISCHES LIEDERBUCH (Wolf) | 2:08 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 20 May 1937, London; 2EA4953-1 (DB3325) | ||

| 7. | Komm, o Tod, von Nacht umgeben, from SPANISCHES LIEDERBUCH (Wolf) | 3:28 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 15 June 1937, London; 2EA4952-4 (DB3326) | ||

| 8. | Der Jäger, from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:21 |

| Michael Raucheisen, piano | ||

| 10 February 1937, Berlin; 2RA1818-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 9. | Lied eines Verliebten, from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:45 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 17 November 1938, London; 2EA7123-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 10. | Fussreise, from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:31 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 17 November 1938, London; 2EA7123-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 11. | Schlafendes Jesuskind, from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:41 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 17 November 1938, London; 2EA7126-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 12. | Der Jäger, from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 3:11 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 20 May 1937, London; 2EA4954-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 13. | Der Musikant, from EICHENDORFF-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:46 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 16 November 1938, London; 0EA7119-1 (DA1672) | ||

| 14. | Der Freund, from EICHENDORFF-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:58 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 16 November 1938, London; 0EA7120-1 (DA1672) | ||

| 15. | Zur Ruh’, zur Ruh’, ihr müden Glieder!, from SECHS GEDICHTE VON SCHEFFEL, MÖRIKE, GOETHE, UND KERNER (Wolf) | 2:32 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 20 May 1937, London; 2EA4953-1 (DB3325) | ||

| 16. | Traum durch die Dämmerung, Op. 29, No. 1 (R. Strauss) | 2:58 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 10 June 1937, London; 0EA4966-1 (DA1581) | ||

| 17. | Die Nacht, Op. 10, No. 3 (R. Strauss) | 2:27 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 15 June 1937, London; 0EA4973-1 (DA1581) | ||

| 18. | Allerseelen, Op. 10, No. 8 (R. Strauss) | 3:08 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 10 June 1937, London; 0EA4967-1 (DA1591) | ||

| 19. | Zueignung, Op. 10, No. 1 (R. Strauss) | 2:01 |

| Gerald Moore, piano | ||

| 20 May 1937, London; 0EA4956-1 (DA1591) | ||

| VI. Selected Lieder by Hugo Wolf Recorded off the Air During a BBC broadcast | ||

| Unidentified pianist, London, 7 December 1938 | ||

| 20. | Der Musikant, from EICHENDORFF-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:57 |

| 21. | Der Freund, from EICHENDORFF-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:36 |

CD 5 (64:07) | ||

| VII. Excerpts from Live Performances | ||

| Teatro Colón, Buenos Aires, 1938 | ||

| 1. | JOHANNESPASSION: O theurer Heiland (Bach) | 5:41 |

| orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Colón, conducted by Erich Kleiber | ||

| 22 September 1938 | ||

| 2. | SIEGFRIED: Heil dir, weise Schmied! (Wagner) | 14:50 |

| with Erich Witte, tenor orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Colón, conducted by Erich Kleiber | ||

| 4 October 1938 | ||

| VIII. Excerpts from Tannhäuser, Parsifal, and Otello | ||

| Orchestra of the Teatro Colón, conducted by Roberto Kinsky, Columbia, Buenos Aires, 1943 | ||

| 3. | TANNHÄUSER: Wohl wußt’ ich hier sie im Gebet zu finden (Wagner) | 4:21 |

| 4 October 1943; C-13216-1 (US Columbia 71697-D) | ||

| 4. | TANNHÄUSER: Wie Todesahnung Dämmerung deckt die Lande ... O du mein holder Abendstern (Wagner) | 3:56 |

| 4 October 1943; C-13217-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 5. | PARSIFAL: Nein! Lasst ihn unenthüllt! (Wagner) | 7:28 |

| 13 September 1943; C-13127-2 and C-13128-2 (Argentine Columbia 266483) | ||

| 6. | PARSIFAL: Ja, Wehe! Weh’ über mich (Wagner) | 6:37 |

| 13 September 1943; C-13125-1 and C-13126-1 (Argentine Columbia 266484) | ||

| 7. | OTELLO: Talor vedeste in mano di Desdemona … Sì, pel ciel marmoreo giuro! (Verdi) | 4:27 |

| with Lauritz Melchior, tenor | ||

| 31 August 1943; 13086-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| IX. Selected Songs by Edvard Grieg | ||

| Franz Rupp, piano, US Columbia, New York City, June 1945 | ||

| 8. | Med en primula veris (Mit einer Primula Veris), Op. 26, No. 4 | 1:11 |

| 8 June 1945; CO 34928-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 9. | Gruss, Op. 48, No. 1 | 1:02 |

| 8 June 1945; CO 34928-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 10. | En svane (Ein Schwan), Op. 25, No. 2 | 2:15 |

| 13 June 1945; CO 34929-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 11. | Og jeg vil ha mig en Hjertenskjaer (Zur Johannisnacht), Op. 60, No. 5 | 1:38 |

| 13 June 1945; CO 34930-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 12. | Zur Rosenzeit, Op. 48, No. 5 | 2:14 |

| 8 June 1945; CO 34931-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 13. | Den særde (Der Verwundete), Op. 33, No. 3 | 2:07 |

| 8 June 1945; CO 34932-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 14. | Jeg elsker dig (Ich liebe Dich), Op. 5, No. 3 | 2:09 |

| 8 June 1945; CO 34933-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 15. | Ein Traum, Op. 48, No. 6 | 2:19 |

| 13 June 1945; CO 34934-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 16. | Lys Nat (Lichte Nacht), Op. 70, No. 3 | 1:49 |

| 13 June 1945; CO 34935-2 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

CD 6 (67:06) | ||

| X. Selected Lieder by Franz Schubert, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms, and Hugo Wolf | ||

| Ignaz Strasfogel, piano, US Columbia, New York City, September 1945 | ||

| 1. | Die Post, No. 13 from WINTERREISE, D.911 (Schubert) | 2:11 |

| 17 September 1945; CO 35204-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 2. | Du bist die Ruh’, D.776 (Schubert) | 3:28 |

| 17 September 1945; CO 35202-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 3. | Intermezzo, No. 2 from LIEDERKREIS, Op. 39 (Schumann) | 2:01 |

| 17 September 1945; CO 35203-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 4. | Fruhlingsfährt, Op. 45, No. 2 (Schumann) | 3:19 |

| 17 September 1945; CO 35205-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 5. | Die Mainacht, Op. 43, No. 2 (Brahms) | 3:08 |

| 14 September 1945; CO 35199-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 6. | Tambourliedchen, Op. 69, No. 5 (Brahms) | 1:43 |

| 14 September 1945; CO 35201-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 7. | Anakreons Grab, from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:42 |

| 14 September 1945; CO 35198-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| 8. | Gesang Weylas, from MÖRIKE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:56 |

| 14 September 1945; CO35200-1 (unpublished on 78 rpm) | ||

| XI. Selected Lieder by Hugo Wolf and Richard Strauss | ||

| Taken off the air from CBS broadcasts, New York City | ||

| 2 February 1948 | ||

| CBS Symphony, conducted by Alfredo Antonini | ||

| 9. | Harfenspieler I: War sich der Einsamkeit ergibt, from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:59 |

| 10. | Harfenspieler II: An die Türen will ich schleichen, from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:03 |

| 11. | Harfenspieler III: Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen, from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 2:06 |

| 12. | Anakreons Grab, from GOETHE-LIEDER (Wolf) | 1:56 |

| 13. | Breit’ über mein Haupt, Op. 19, No. 2 (R. Strauss) | 1:45 |

| 26 January 1944 | ||

| CBS Symphony, conducted by Bernard Hermann | ||

| 14. | Hymnus, Op. 33, No. 3 (R. Strauss) | 4:43 |

| 15. | Pilgers Morgenlied, Op. 33, No. 4 (R. Strauss) | 3:43 |

| 16. | Cäcilie, Op. 27, No. 2 (R. Strauss) | 2:02 |

| XII. Excerpts from DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG (Wagner) | ||

| US Columbia, New York City, 1945 and 1947 | ||

| 31 May 1945 | ||

| Orchestra conducted by Paul Breisach | ||

| 17. | Was duftet doch der Flieder (Monologue, Act 2) | 5:47 |

| XCO 34876 and XCO 34877 (71819-D) | ||

| 18. | Wahn, Wahn, überall Wahn (Monologue, Act 3) | 6:36 |

| XCO 34878 and XCO 34879 (71820-D) | ||

| 7 December 1947 | ||

| Orchestra conducted by Max Rudolf | ||

| 19. | Mein Kind, von Tristan und Isolde … Selig, wie die Sonne (Quintet, Act 3) | 8:22 |

| with Polyna Stoska, soprano; Torsten Ralf, tenor; Herta Glaz, mezzo-soprano; and John Garris, tenor | ||

| XCO 39277 and XCO 39551 (72518-D) | ||

| XIII. Excerpt from Act 3 of DIE WALKÜRE (Wagner) | ||

| New York Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Artur Rodzinski New York City, 25 November 1945 | ||

| 20. | Leb’ wohl, du kühnes, herrliches Kind (Wotan’s Farewell) | 14:33 |

Producers: Ward Marston and Scott Kessler

Associate Producer: Iain Miller

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston and J. Richard Harris

Photos: Girvice Archer, Gregor Benko, Rudi van den Bulck, Peter Clark (Curator of the Metropolitan Opera Archive), Bill Ecker, Iain Miller, Paul Steinson, André Tubeuf, and Axel Weggen

Booklet Coordinator: Mark S. Stehle

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Booklet Essays: Michael Aspinall and Iain Miller

This project has been fully funded by an anonymous donor.

Marston would like to thank the following for making recordings available for the production of this set: The estate of Richard Bebb with help from Owen Williams; Stephen Clarke; Carlos Osvaldo Garde; Lawrence F. Holdridge; Karsten Lehl; Timothy Lockley; Norbeck, Peters and Ford; Fabian Piscitelli; Paul Steinson; and Axel Weggen.

Marston would like to thank William Crutchfield for his editorial guidance.

Marston would like to thank Christian Zwarg for his invaluable help with providing important discographic information.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

HERBERT JANSSEN (1892–1965)

by Iain O. Miller, ©2017

PREFATORY NOTE: Anyone who writes about Janssen must first acknowledge a debt to the excellent 1965 article by Ted Hart (1921–1970) in the “Record Collector”. Ted Hart was himself a singer and an accomplished musician; he was also a friend of Janssen’s and may even have studied with him. After Janssen’s death, his wife gave Hart access to whatever recordings and scrapbooks of reviews remained in their flat at the Ansonia Hotel in New York. In addition to material gathered during his own research, the present compiler has drawn extensively on Hart’s article for information that is currently unavailable elsewhere.

• • • • •

JANSSEN’S EARLY LIFE AND VOCAL STUDIES

Even during what is now looked back on as one of the ‘Golden Ages’ of singing, there was always an air of exceptional distinction around the name of the German baritone, Herbert Janssen. This distinction was remarked by critics and audiences very early in his career and now, a hundred and twenty-five years after his birth, it remains, undiminished, in the judgment of anyone with a love of fine singing.

According to his birth certificate, Herbert Janssen was born on the 23rd of September, 1892, at 59 Brabanterstrasse in Cologne, the son of one Hermann Janssen and his wife, Anna Luise Sophia, née Siewert. On this certificate, Hermann Janssen gave his profession as ‘Merchant’ and according to his son’s account he was the owner of a coal mine and a coal merchant. Janssen used to say that he was of Frisian origin. The family was not only well-to-do, but also extremely cultivated, with several writers, sculptors, and painters amongst its members. In fact, the well-known painter Johann Peter Hasenclever was Herbert Janssen’s great-grandfather. Janssen’s mother was very musical and was herself a gifted amateur singer. Naturally she saw to it that her son and her daughter Anna should, as children, take singing lessons from a Cologne voice teacher, a Madame Batz-Kalender. Even as a child, the young Janssen enjoyed giving performances of operas before family and friends using his model opera house and singing all the parts of, say, Oberon, or Undine, in a high soprano. He was also so talented a pianist that at one time he dreamt of becoming a professional pianist. Cologne was musically and artistically very lively and the Janssen family fully enjoyed the city’s cultural life. As he grew up, Janssen began to think of becoming a singer, but he kept these ideas to himself and the intervention of military service and a full four years of active service as a cavalry officer in the Great War delayed any decision.

At the end of the War, Janssen’s thoughts on the matter had matured and he announced to his family his wish to become a professional singer. They were absolutely appalled, and to subsequent generations, who know Janssen’s great artistry, their attitude will seem benighted. But one must remember that though they really were culturally enlightened people and took genuine and profound pleasure in music, from their point of view it was one thing for them to enjoy these things as gifted amateurs or as listeners of good taste, and quite another for their son to become a professional on the stage and to be paid to sing for the enjoyment of others.

Janssen’s father had died when he was quite young, and when Janssen announced his intentions, his mother and various uncles immediately gathered round and exhorted him to study the law or go into the church, as befitted a member of his family; they pointed to his elder brother, Ernst, who had studied medicine, as the example to follow. But during the War, Janssen had thought constantly and profoundly about his career and was absolutely determined to study singing. His family, on the other hand, was equally adamant that he should forget such outlandish ideas, come to his senses, and enroll in a law school.

Eventually a conditional compromise was reached: his family proposed that they would arrange for him to sing an audition before a famous voice-teacher from Karlsruhe, chosen by them, and if this teacher should give his approval, then the family would agree to finance Janssen’s voice lessons. If, on the other hand, he ruled against his prospects as a singer, then Janssen would abandon singing as a career and study law.

At the audition, Janssen was certain he had sung well and expected that his singing would be praised. But to his great astonishment, the teacher gave judgment against him: he had no voice and no hope of cultivating it into anything that would support a career. Fortunately, Janssen remained quite unconvinced by this but, in accordance with the agreement, he duly went to Berlin and enrolled in the university there, ostensibly to study law. In fact, he used to say, he never went near the law school. Instead, he sought out a singing teacher and began to study.

Throughout his career, reviewers, no matter what other virtues they mentioned, constantly commented on how “well-schooled” Janssen’s voice was. Comments to that effect crop up again and again to this day when his singing is discussed. Ted Hart quotes Janssen as answering the inevitable question about how he acquired this technical prowess with the quietly teasing remark, “Constant study and training—but in the right way”, this last phrase added “as if in subtle afterthought”, says Hart.

The “right” way for Janssen was the way of the Berlin voice teacher he had chosen to study with, the great Dr. Oskar Daniel. This extraordinary man, though often given passing mention in singers’ biographies, deserves a central place in an account of Janssen’s career. He was born in Oedenburg (now Sopron, in Hungary) in 1879. His mother tongue was German and he received a doctorate in law from Vienna in 1906. Because he was extremely musical, he had been studying singing at the same time and had become a protégé of Gustav Mahler. A student of Janssen’s quotes him as saying that Daniel had studied with the younger Lamperti, who taught in both Dresden and latterly in Berlin. I have not been able to confirm this with independent evidence. What is definitely known is that he studied singing in Milan with Vincenzo Lombardi (1856–1914) teacher of de Lucia and Caruso, and also with Vittorio Vanzo (1862–1945). He was taken on as a “jugendlicher Heldentenor” at the Trier Opera for the 1911 Season and seems to have remained there until the outbreak of the Great War. Apart from having an unusually beautiful voice, Daniel soon showed himself to be an extremely gifted teacher of singing and, as a person, he is described as being lively and friendly. He quickly rose to the top of his profession as a teacher and, by the time Janssen went to study with him, he was already famous and had many celebrated pupils. A list of his pupils would be too long to include here, but in fairness to his memory, one can scarcely neglect to mention that amongst singers who studied with Daniel at some stage of their careers were Maria Cebotari, Frieda Hempel, Göta Ljungberg, Margherita Perras, Erna Sack, Lotte Schöne, Paul Schöffler, Elisabeth Ohms, as well as Herbert Janssen. Famous actors or theatre personalities also studied voice production with him, either privately or at the Berlin Hochschule. Marlene Dietrich, Elisabeth Bergner, Erika Mann, and Klaus Mann were among them.

When Dr. Daniel was appointed professor of voice training at the Berlin Hochschule in 1922, he was already so famous that the Berlin newspapers were extraordinarily enthusiastic. In fact, such was his fame that the noted Viennese psychologist Dr. Leopold Thoma came to observe his classes and afterwards published an account of what he’d seen at the lessons and what he had discussed with the man he calls ‘The Master’. The article, journalistic, not scholarly in style, has as its title one of Daniel’s exhortations to his pupils: “The core of the tone at the point between the eyes” and underneath, “Draw the tone in from outside, not from inside!” Beneath this is a sketch, showing the pupils seated in a line, a pianist at a grand piano and ‘The Master’ standing beside the piano with his hand on his throat saying, “Not here! Concentrate the tone between the eyes!” Dr. Thoma goes on to describe the lesson and explains Daniel’s practice of group lessons (Lamperti did this too) and describes how each singer in turn gets up, with thumb or finger on the forehead, and sings before the others and then submits to the comments of the teacher and his fellow pupils. When he asks Professor Dr. Daniel why he has the singers hold their finger on the place between their eyes, Daniel replies with what, at first, must seem a perfect example of explaining obscurum per obscurius. He says:

The best way to explain is with a comparison. If you light a carbon-arc lamp, a point of light emerges at the point where the carbon rods meet, from which light rays are emitted. It is the same with the voice and the point between the eyes. This is my opinion regarding the building of the core of the vocal tone.

Oskar Daniel held an important position in Berlin’s cultural life and the artists and intellectuals of Berlin often met at his beautiful house in the Kaiserallee. Heinz Tietjen, Bruno Walter, whose daughter also took singing lessons from Daniel, Leo Blech, both Heinrich and Thomas Mann, Otto Klemperer, Emil Ludwig, and Max Reinhardt were all among the many regular distinguished visitors to the Daniels’ hospitable salon; years later, several recalled their visits to his house, the evenings of conversation and music surrounded by the beautiful furnishings, the wonderful Persian carpets, and the lovely paintings on the walls. The house and the life within it were to vanish, of course, with so much else of German high culture, in 1933.

• • • • •

Janssen used all the money sent to him by his family for his voice lessons. For almost two years he kept these studies from them, but a sudden visit by his mother revealed to the family what had been going on. Of course, they were furious and funds were abruptly cut off. He was told that there would be no further support from them until he abandoned singing and began to study law. For Janssen, such a course was more than ever out of the question and he was obliged to finance his continuing studies with Dr. Daniel by giving voice lessons to beginning singers and by accepting such support as his sympathetic brother-in-law was able to give.

He studied diligently and in 1922 went for his first audition: remarkably, he was immediately engaged by Max von Schillings at the Berlin Staatsoper. He telegraphed a message to his family in Cologne: “Engaged Berlin Staatsoper” and was amazed to have a grand piano delivered to his flat almost within hours. It was a present and a declaration of peace from his mother.

There was more to be revealed, however. It was only eight years later, in the afterglow of Janssen’s engagement to sing at Bayreuth, that his mother dared to tell him a terrible truth about the crucial audition she and the family had arranged years before: the teacher from Karlsruhe who had told him he had no voice had been given a large sum of money in advance, with instructions from the family that he must discourage Janssen from ever attempting to become a professional singer.

JANSSEN’S RECEPTION AS A SINGER

Of course, Janssen’s triumphant success at his audition before Max von Schillings did not mean an instant advance into taking major roles. He made his debut, on horseback, on May 5th, 1922, in Schrecker’s Schatzgräber. Despite his years in the cavalry, he had to twist himself sideways in the saddle to sing, as the nervous animal refused to face the audience. Leo Blech, the conductor, remonstrated with him afterwards for not ‘singing out’! He then began the usual ‘cursus honorum’ as a comprimario, singing Melot, Montano, Silvano in Ballo in Maschera, as well as small roles in Tiefland and Palestrina. It is obvious, however, that even in his first season Blech, and others, were already aware that with Janssen, they had exceptional material. Oskar Daniel’s training was telling, and Janssen was given the important and highly declamatory role of the Heerrufer in Lohengrin as well as the lyrical role of Silvio in Pagliacci. The critics wrote: “A fine baritone, full of character”; “Mighty and noble toned”; “well-schooled and sonorous”. It was a remarkable first season.

In fact, Janssen’s first season was so successful that already, in his second season, he was entrusted with the major role of Wolfram in Tannhäuser. His performance of this role was immediately recognized as being of exceptional beauty and finish; so much so, indeed, that as early as December 1923 he was invited to the Odeon Studios to record two excerpts from the opera, his only acoustic recordings. He also added to his repertoire the roles of Sharpless, the Count di Luna, and that of Liebenau in Waffenschmied. Janssen used later to say that he thought that perhaps it was his singing of Wolfram that had enabled him so quickly to leave the comprimario repertoire and become a singer of major roles. Even now, nearly a century later, his singing of Wolfram’s music is held up as a standard of how well that role can be sung.

Hart, using Janssen’s own archive, gives an illuminating list of roles performed by Janssen at the Berlin Staatsoper in his first years. It is a daunting and demanding repertory. In the 1924–1925 season, he added Renato, one of his favourite and most successful roles, Iokanaan, the Tsar in Zar und Zimmermann, and the Count in Schrecker’s Die Ferne Klang. In the 1925–1926 season, he added Gunther, Kurvenal, Albert in Werther, the Secretary in Boris Godunov, and Lothario in Mignon. And, incredibly hard work though it was, in 1926–1927 he added no fewer than eight new, major roles: Escamillio, Tonio, Valentin, Orest, the Count in Figaro, Amonasro, Amfortas, and Carlo in Forza del Destino!

After his retirement, he recalled having once sung Silvio in a performance of Pagliacci in which Battistini sang Tonio. When and where can this have been? Janssen’s guest appearances are hard to trace: they began early on, first in and around Berlin itself, but eventually in Paris, Barcelona, Prague, Copenhagen, Antwerp and The Hague, Kiel, Geneva, Lyons, and in Dresden, Hamburg, Nuremberg, Kassel, and Vienna—all over Europe, in fact, except Italy. Janssen’s appearance with his great predecessor could have occurred in many places, but so far, it has not been possible to trace such an occasion. In any case, Janssen’s admiration for Battistini’s singing knew no bounds and I mention this because the German critics and audiences, from the beginning, found Janssen’s own singing “Italian” in character and highly idiomatic for Verdi and other Italian composers. One German critic wrote of him as “a German singer who has the Italian quality, the lyricism, the flowing, fresh vocalism ...” In Berlin, he was described as “Janssen, the Belcantist”, this familiar epithet no doubt referring to his ‘instrumental’ flow of beautiful tone. Janssen himself once said that he had spent nearly an entire year singing “Il balen” every day, until he felt that he had this demanding aria perfectly under control. He would also recall how, when he was beginning his studies, he wanted to sing nothing but Arie antiche.

It must be emphasized that within Germany, Janssen sang Verdi and Italian opera a great deal and that he always felt a special affinity towards this repertoire. In addition to the Verdi roles already mentioned, he was a famous Rigoletto and Iago. He also sang Charles V in Ernani and Posa in Don Carlo with great success. It’s a great shame that he was able to record almost nothing of his preferred repertory. There is the Rigoletto duet with Lotte Schöne of which one critic remarked, “Nearest the art of the Italian comes Herbert Janssen with his smooth baritone”, and of which recording Herman Klein wrote that Janssen was first class and had “the right sort of appealing voice for Rigoletto.” Two takes under Blech of “Si pel ciel” from Otello with Melchior were never published but three takes of the singers’ much later recording of the same music have survived. There is the duet from Butterfly with Margherita Perras, but nothing else to help one imagine Janssen’s voice and art in Italian music.

Among contemporary operas in which Janssen performed, by far the most important was the 1927 Berlin premiere of Busoni’s masterpiece, Doktor Faust under Blech, whom Busoni had always especially admired. The great Friedrich Schorr was in the title-role, Frida Leider was the ‘Duchess of Parma’, and Janssen was the ‘Maiden’s brother, a soldier’. Janssen’s scene, with its pealing organ music, and its grandly declamatory line, must have been glorious to hear. Certainly, he enjoyed singing it, as he told Oskar Daniel, who had little sympathy with the music and had come backstage to commiserate with “poor” Janssen for having to sing in the opera. Reviews of his performance, however, were full of the highest praise and several critics thought Janssen’s performance was some of his best work to date.

Other less commonly performed operas were also in Janssen’s repertory. He took part in Karol Rathaus’s Fremde Erde, Moniuszko’s Halka, and Herbert Windt’s Andromache.

For the May-to-June season of 1926, Janssen came to Covent Garden for the first time. He was to appear there every year until the outbreak of the War and was highly esteemed from his very first appearances. In his first season he sang Gunther and Kurvenal only, and the critics were enthusiastic. In the Covent Garden of 1926, Janssen immediately stood out even where singers of an older generation such as Melba, Chaliapin and Journet were still performing, and where Schorr, Leider, Lotte Lehmann, Melchior and Schumann were also singing. His Gunther was called “a remarkable piece of singing” and “unusually convincing” and his Kurvenal “combined power and sympathy”. Indeed, throughout his career, his singing of Gunther always provoked surprised delight at what Janssen could make of that unsympathetic role. It was as though the critics were noticing, were hearing Gunther’s music for the first time. I think that the surprise and the delight of those audiences can be shared by us unusually well in the excerpts recorded live at Covent Garden under Beecham: although we cannot see Janssen’s acting of the role, there is something instantly arresting about the way his voice takes charge of the entire stage and commands attention. In fact, this is always true of Janssen’s singing and it is one of the more striking virtues of his art. It stems, I think, from the stance which Janssen takes up towards the music. It is a question of address, of bearing, of tremendous presence: Janssen used to call this quality “Heil”. It is also, of course, to do with the voice itself, its placement, its firm tonal core, and, not least, its great beauty. Even after the high drama of Hagen’s summoning of the Vassals, the almost magical effect of Janssen’s voice in the brief solo which follows, recalls Homer: he begins to sing “and down the shadowy halls, all were silent, seized by rapture.” Yes, it’s like that.

Janssen remained an honoured guest at Covent Garden until the close of the 1939 season. And, while he was indispensable in the Wagnerian roles, he was occasionally given the opportunity to display his talents outside Wagner: as Hidraot in Gluck’s Armide with Leider and Widdop, where he “sang finely” and where his “fine, resonant voice was a joy to hear”; as Prince Igor, where, in a cast that included Kipnis, Janssen was the only singer praised for his style, while the remaining singers were thought “too German”; as Orest in Elektra; Don Fernando in Fidelio; and as the Speaker in the Zauberflöte, where Herman Klein found him “simply perfect” and Cardus thought there was “more wisdom in one syllable of Janssen’s Speaker” than in all of Sarastro’s role. The air of wisdom in Janssen’s singing is something that comes back repeatedly when critics try to describe its effect.

It was in Wagner, however, that he left his stamp most definitely at Covent Garden. He sang Donner in Rheingold, as well as the major roles for which he is chiefly remembered: the Dutchman, Wolfram, Telramund, Gunther, Kothner, Kurvenal, and Amfortas. His Dutchman was considered one of his finest achievements: Ernest Newman wrote of it that it was “one of the truly great things of the operatic stage today; here is a sufferer who carries on his shoulders not only his own but the whole world’s woe.” And Legge, writing as ‘Beckmesser’, wrote: “As in all his work, he stood apart from all the rest of the company by reason of his exquisite singing and his complete absorption in the character.” Finally, many years later, Will Crutchfield, referring to the live recording of one of these Covent Garden performances of Holländer, would write of the “almost unbelievably beautiful singing from Flagstad and Janssen.”

Wolfram was a role that suited Janssen’s style and aesthetic perfectly. When Siegfried Wagner and Tietjen invited him to make his debut as Wolfram at Bayreuth in 1930, he went to his first rehearsal with Toscanini and sang through the role without interruption from the conductor. When they reached the end, Toscanini simply closed the score and said, “I see that it will not be necessary for us to see one another until the first full dress rehearsal.” When the recording of this production, under Elmendorff, was released by English Columbia, Herman Klein wrote an ecstatic review of it. Warning himself, at the start, not to use up all his superlatives too soon, and having praised the entire production, he comes to the Tournament of Song which he says is performed on the ‘grand scale’ and then he adds: “I think the supreme touch of beauty … comes from the singing of the part of Wolfram by that admirable artist Herbert Janssen; it is not less replete with poetic than vocal charm.”

It was much the same with Tristan. Berta Geissmar, the learned and highly musical secretary, first to Furtwängler and later to Beecham, tells us that no matter where in Europe the opera was to be sung, Leider, Melchior, and Janssen were secured first, as a team, and the Brangäne and King Mark allowed to vary according to availability. Neville Cardus wrote of Janssen’s Kurvenal that it was “one of the most movingly beautiful pieces of work I have ever known … his singing and acting alike were wounding to the heart in Act 3.”

Janssen’s Amfortas, too, received extraordinary praise from the critics—indeed it still does. Walter Legge, writing as ‘Beckmesser’ once again, wrote of a 1937 Parsifal: “He still stands immeasurably superior to other German baritones, tenors and basses in vocal culture, and without sacrificing any beauty of tone, he conveys even more vividly than before the drained weariness of a man racked by spiritual and physical suffering.”

Friedelind Wagner records that when Janssen had suddenly to substitute for a Bayreuth Amfortas who was indisposed, the famously demanding conductor Karl Muck called from the orchestra, “That’s the first Amfortas I’ve heard since Reichmann”, the creator of the role and a pupil of the elder Lamperti.

The indelible impression left by Janssen’s Amfortas and Wolfram comes across well in an article written for Opera by the music critic, Alec Robertson (1892–1982), just after the singer’s death. Robertson says that he had been a ‘regular’ at Covent Garden since 1910 and first heard Janssen there in 1927 as Amfortas. At the end of the first act, he and his fellow regulars had decided that they had been listening to a “great” singer and Robertson adds that for him, Janssen’s was the most beautiful baritone voice he had ever heard. Nearly forty years after the event, he can still vividly recall the singer as a stage presence and how, even after the “revelatory experience” of Chaliapin’s acting, he was “greatly impressed by the power of Janssen’s acting in his various roles.”

I recall, especially, his economy of gesture. In the Act I Grail scene of Parsifal, he did not flail his arms about in Amfortas’s anguished solo, so that when he did raise them up at the impassioned cry of ‘Allerbarmer, ach! Erbarmen!’, the supreme gesture conveyed all the terrible suffering of the penitent knight.

Equally moving, in a quite different way, was his tender gesture to Elisabeth in the last act of Tannhäuser, asking to accompany her up the mountain side, and the way [his] eyes followed her up the path. The poignant beauty of his tone in ‘O Star of eve’ is something I shall never forget.

He remembers, too, Janssen’s “touching” Kurvenal and how his portrayal of Kothner was “the very spit of a petty official anxious to make the most of a moment of power and the display of his vocal virtuosity.”

These snippets of reviews and memories don’t, of course, tell us all we want to know but they do, I think, give a glimpse of what was special about Janssen’s art: the beautiful and very individual voice, instantly recognizable; the perfectly even emission and Italianate legato; the sensitive response to the words as set to music—what Ernest Newman called “that fine jeweller’s art of his”; and an extraordinary ability to make, through his singing, each character entirely distinct. Legge, writing about a 1936 Meistersinger, sums up this last talent with characteristic vigour:

Janssen’s Kothner was the best individual figure on the stage … The Isolde and Brünnhilde of Flagstad are patently one woman, and Bockelmann’s Wotan is disturbingly like his Sachs, but there are no points of similarity between Janssen’s genial Kothner, his suffering Amfortas, his stupid, frustrated Gunther, and his rugged, devoted Kurwenal. There is only one feature common to the characters Janssen creates—they invariably sing as well, if not better than, anyone else on the stage.

The fact that this ability to give life to a character arises not only from his skill as an actor, but from the way Janssen sings and colours his voice, means, I think, that we can still collect a good deal, if not all, of what Legge is talking about from Janssen’s records.

But what records? The question arises because Janssen’s recording career has certain oddities which have been remarked by all of his admirers. After all, when one considers his operatic successes and popularity in Berlin, in the summer festival at Zoppot, at Bayreuth, Covent Garden, Paris, Prague, and Barcelona—where, incidentally, he sang Kurvenal to Melchior’s first Tristan— one would have expected a rich and varied operatic discography. Instead, one is confronted with relatively few recording sessions for continental European companies and a patchy repertoire curiously unrepresentative of his most famous stage roles apart from that of Wolfram. There are the two duets previously mentioned from Butterfly and Rigoletto, Valentin’s Cavatina and Death from Faust, an aria from each of Lortzing’s Waffenschmied and Zar und Zimmermann, a duet with Ljungberg and a solo from the Benatzky operetta Die drei Muskatiere, and some solo scenes from Tannhäuser. From the other Wagner operas, in which, after all, he had major successes, the only prewar studio recording is the unissued trio from Act II of Götterdämmerung. There was an attempt by Electrola in 1928 at a live recording from the Staatsoper of a complete Cavalleria rusticana with Janssen as Alfio, but the masters no longer exist and no excerpts were issued. One can only wonder why the European companies recorded so little. It seems that from 1930 onwards, all Janssen’s prewar records were produced by (or for) English Columbia, or HMV.

Janssen himself seems to have minded that opportunities were being lost: in a letter from him to his English producer, Walter Legge, in early 1936, he actually writes, “I would of course be only too happy to make some new Lieder records but I regard it as much more important at the moment to make orchestral recordings (Amfortas or suchlike) which would indeed sell fabulously well in London during the season and equally in Bayreuth.”

But Lieder were at the centre of Legge’s interests just then. In 1932 he had founded the London Lieder Club, in part, at least, to provide support for the Hugo Wolf Society records, which had just been launched. Recitals at the London Lieder Club were very grand affairs altogether: they took place in the Dorchester Hotel—and later at the Hyde Park Hotel—on Sunday evenings over two months and subscribers paid a fee of three guineas for the series and wore evening dress. The patrons included ten ambassadors and even royalty. (One hopes that the atmosphere of the concerts was one of intelligent pleasure rather than the devotional one which often prevails at such gatherings.) Certainly, the audience heard the greatest Lieder singers of their age, amongst them Gerhardt, Tauber, McCormack, Hüsch, Schorr, and Janssen. A programme of one of these concerts tells us that Janssen, accompanied by Ivor Newton, sang a group of Brahms, followed by Schubert, ending the first half with Die Allmacht, a recording of which is published here for the first time. The second half began with songs by Schumann and ended with Wolf. The programme prints the words of each Lied but only in German, which the audience was evidently expected to understand.

It is likely that Janssen appeared in every one of the Lieder Club’s annual series of concerts, but I have found no certain corroboration of this. In March of 1938, he took part in the second Serenade concert at Sadler’s Wells, accompanied by the London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Menges and sang the three Harfenspieler Lieder, in Wolf’s own orchestrations, with great success. (He also sang the Count’s third act aria from Figaro in the second half of the concert.) Hart mentions that as early as 1924 Janssen had become eminent as a concert artist and that he would include opera excerpts on these occasions. He quotes a critic who praises Janssen for his “joyful song-art”. But despite the obiter dictum attributed to Janssen to the effect that he “only sang opera so that [he] could sing Lieder”, I have only definitely traced one Lieder concert in Germany: a concert of Richard Strauss’s music, with the orchestra conducted by the composer, at which Janssen sang four of the larger songs: Pilgers Morgenlied, Hymnus, Notturno and Nächtlicher Gang. Later performances of the first two of these, taken from recordings in Janssen’s own collection, have recently appeared on Marston’s edition of Strauss songs.

Whatever his concert activity in the field of Lieder may have been, Janssen’s recordings of songs by Schubert, Schumann, Brahms, Wolf, and Strauss continued to appear throughout the 1930s. But, despite Janssen’s pleas to Walter Legge, no opera recordings were made in the studio in this period. Live recordings were made as “technical tests” from performances at Covent Garden and included parts of performances of Götterdämmerung with Leider and with Flagstad; a complete Tristan with Melchior and Flagstad; Janssen’s part in Holländer, again with Flagstad; and most of his wonderful performance as Amfortas in Parsifal. But of these, the only record issued at the time was a brief excerpt of his previously mentioned singing of Gunther under Beecham, and Janssen’s dream of making further operatic recordings remained unfulfilled for the time being.

The London Lieder concerts and records formed a sort of parallel career for Janssen. The records were extremely well received at the time of their release and have remained ever since among the great classics of the gramophone. Ernest Newman dubbed Janssen the “Prince of Lieder singers” and, in due course, Legge, in a letter to the Gramophone, raised him to “King of Lieder singers” and when Elgar brought Delius an album of the Wolf Society Lieder to listen to, Delius, although he disliked Wolf’s music, nevertheless wrote, “Herbert Janssen sings [the songs] beautifully with the deepest feeling, every syllable declaimed perfectly, with just that graveness of voice that gets to the very heart of the words”. In our own time, J.B. Steane, a great admirer of Janssen’s singing, was still wishing that it had been Janssen who had recorded the Winterreise complete for HMV.

Years later, Legge wrote a description of how he remembered the preparation that went into the recording sessions of Lieder with Janssen and Gerald Moore, describing them as some of their happiest working hours:

Time did not matter. Day after day, at Abbey Road, or in Gerald’s charming studio, we worked at Wolf and Schubert songs, phrase by phrase, bar by bar, nuance by nuance. Then, after an evening’s recording at Abbey Road, there was the excitement of hearing the first pressings and, in the light of that experience, more rehearsal before recording again. In some cases the production of what we considered a satisfactory recording of a song was spread over years. And when we were satisfied, there was the pleasure of taking the records down to Ernest Newman for his approval.

JANSSEN FLEES HITLER’S GERMANY

In her book, The Baton and the Jackboot, Berta Geissmar gives a detailed picture of how very quickly things deteriorated in Germany after Hitler came into power in early 1933. Oskar Daniel was one of the first to be dismissed from his post at the Hochschule, on “racial” grounds, to the great dismay of his students and to the outrage of people like Janssen. This event, together with what his friend, Ted Hart, calls his independent judgment and high principles fixed a gulf between Janssen and the Nazis and having a certain esprit, he was given to making derogatory remarks about the regime and its supporters in a dangerously public manner. In spite of this, Janssen’s international prestige was such that, for the time being, he was kept on at Bayreuth and the Berlin Staatsoper and also allowed to continue to sing outside Germany. But his known attitude towards the Nazis, together with his satirical and biting remarks about them, made him an obvious target for their revenge. Stories circulate with different versions of what precipitated the final fall of the axe, but entries in Goebbel’s diary in the summer of 1937 make it clear that the Nazis were determined to find some pretext for arresting Janssen and only waiting for the opera season to end before they acted. One story has, I think, the ring of truth: Janssen, after singing before Hitler in 1937, had been summoned to dine with him and had said too publicly, “I may sing for that man, but I will not eat with him” and had ignored the invitation. Whatever the immediate cause may have been, Geissmar makes it clear that years of jealousy and gossip in opera circles, and the constant spying, which is part of daily life in dictatorships, probably all played their part.

At the end of October 1937, the Gestapo pounced, but not before Janssen was warned—in all likelihood by Winifred Wagner or Heinz Tietjen—that they were on their way to arrest him. He escaped in the nick of time, and made his way to Berta Geissmar in England, arriving penniless and looking gaunt, according to Friedelind Wagner. Geissmar took him straight to the BBC to see Toscanini, who was rehearsing for his broadcast of the Beethoven Ninth on November the 3rd. The sympathetic Toscanini could offer him engagements for the next Salzburg Festival and Janssen gladly accepted them. HMV provided him with some money owed from his record royalties and Beecham, with characteristic kindness, immediately included him in a concert scheduled for November the 7th, where the resilient Janssen sang “Die Frist ist um” from Holländer, of all taxing scenes.

Back in Germany, Erna Carstens, his companion of many years, was picked up and interrogated by the Gestapo. She handled herself with great intelligence, pretending to hate Janssen, and was finally released. She, too, made her way to England where she and Janssen soon married.

Janssen’s life and career were obviously now in a state of crisis. All his savings, German and international, were locked in Germany. Furthermore, his refugee status put an end to certain recording projects already under way and planned. Legge had assembled a team of singers to record the complete Schwanengesang, the second volume of the Brahms Song Society set, and to complete the sixth and start the seventh volume of the Wolf Society sets. Before he fled Germany, Janssen, together with Gerald Moore, Marta Fuchs, Rosewaenge, Karl Erb, Hüsch, and Legge had all met in Berlin for recording sessions, and Janssen had made what were to be his last Berlin recordings at the end of August of 1937. (Some of these sides are published here for the first time.) Further sessions had been planned for September 1939 in London, but the outbreak of war put an end to these plans, and the Brahms volumes and the Schubert cycle were never completed.

As for the opera recordings Janssen was so anxious to make, he had, in fact, been wanted for the Speaker in Beecham’s projected Berlin recording of Zauberflöte, together with Tauber and others. But by this time both Tauber and Janssen were refugees from Hitler’s Germany and the recording had to be made without them.

After his arrival in England as an exile, Janssen had to start a new career wherever he could find engagements. He was, of course, very busy at Covent Garden throughout the 1938 season, had several good engagements in Paris in Figaro, and he had been engaged immediately and with much joy by the Vienna Opera in December 1937. There, between early December and the first days of March, he sang Telramund, Scarpia, Don Fernando in Fidelio, Tonio, Scarpia again, Amonasro, and a repeat of Telramund. On the 19th of December, 1937, Janssen wrote from Vienna to Walter Legge:

Everything is marvellous here. The audience idolizes me and the newspapers are full of the highest praise. Nevertheless, I do not want to stay here permanently… Yesterday, I sang Scarpia here with tremendous success and after that have 12 evenings with the Opera here up to the 12th of May.

It was not, of course, to work out like that: the Anschluss took place on the 12th of March, 1938, and once again Janssen and his wife, who had joined him in Vienna after clearing out as much as she could from his Berlin flat, were barely in time to escape the Nazis’ clutches, on this occasion, it is thought, with the help of the distant Toscanini, through connexions set up by him.

In addition to his definite engagements at Covent Garden, Janssen was also considering offers from an agent to sing in Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, at the Metropolitan, and in Buenos Aires and “as many concerts as [he] wanted”. But despite his Vienna success and the hope of work in America, he wrote to Legge in January that his nerves were in shreds with tension and begged him to remember that they were not made of steel and also that it was in their common interest for him to remain “fit enough to work as long as possible.”

Obviously, he was conscious that he was at a turning-point in his career. His life savings were gone and, clearly, finding engagements in Europe was getting ever more precarious owing to the political situation and his refugee status. Nazi sympathizers among the singers brought to Covent Garden from Germany created tension there by attacking their anti-Nazi colleagues. There was also the major problem of his repertoire: outside Germany and Austria, nearly all his engagements were for Wagner, not for the Verdi or the other Italian and French operas he loved, and Janssen must have realized that unless he took rather drastic steps, his repertoire would be limited to only a very few operas. I think it was at this point that Janssen began to consider attempting other, heavier Wagner roles.

The change in Janssen’s thinking about repertoire is evident in his surviving correspondence. In the January 1938 letter to Legge mentioned above, he reminds Legge that the previous September, he had told both Beecham and Legge that he would not sing the role of Sachs in Meistersinger, adding that Tietjen must already have told them that the part was unsuitable for him to sing and would harm him, if he tried it. Yet as early as December 1939, having spent the previous summer studying the role, he was to undertake Sachs twice at the Metropolitan in New York. Furthermore, after singing the Wanderer in Siegfried in four performances at the Teatro Colón in October of 1938, he was evidently heartened enough to go firmly against the advice of both Legge and Beecham, writing to the former in May of 1939 that “after mature reflection and for many pertinent reasons, I am sticking to the decision I have already given you to sing a Wanderer or Wotan this season—come what may.” He actually asks Legge to stop “tormenting” him on the subject and says that he has written a similar request to Beecham.

JANSSEN’S AMERICAN CAREER

Janssen arrived in America, where he would live for the rest of his life, on the 17th of January 1939. In the light of the above remark concerning the heavy Wagner roles he undertook there, it is clear that we must try to make a more carefully balanced report of his career in the Americas than the summary one so often found in encyclopaedic sources. This account states baldly that Janssen was “induced”, “persuaded against his will”, even “forced” to sing these roles owing to the gradual withdrawal of Friedrich Schorr, his incomparably great predecessor at the Metropolitan, and the lack of any more suitable substitute. As we can see from Janssen’s own words quoted above, at least at first, the decision to sing these roles was very definitely his own. The ‘standard’ account goes on to say that the singing of these roles did, in fact, harm his voice and, though he retired at the perfectly reasonable age of sixty after a career of thirty years, that by singing these roles he significantly shortened his career. Both the written evidence of the reviews, however, and the aural evidence of live recordings of Janssen’s singing of the Wanderer, Wotan, and Hans Sachs in New York and Buenos Aires, suggest once again the need for a distinctly more nuanced understanding of what actually happened. So, to get this matter cleared up before embarking on a chronicle of his reception and career in America, let us see what this evidence shows.

As we have already noted, Janssen sang his first Wanderer in Buenos Aires in October of 1938. Erich Kleiber was the conductor and his fellow singers included Konetzni, Max Lorenz, and Rise Stevens as Erda. A recorded excerpt from Act I of the Wanderer’s scene shows that Janssen sounds just wonderful and sings his part very beautifully, as one would expect. The first performance of which I’ve seen reviews, however, took place unexpectedly, and with the Metropolitan Opera in Philadelphia on January the 24th, 1939, before his official debut in New York as Wolfram, four days later. Of his performance in Siegfried (under Leinsdorf and with Flagstad and Melchior) Henry Pleasants wrote:

There was a new Wanderer in the person of Herbert Janssen who was making his American debut and who seems to be about the best German baritone to have trod the boards of the Academy since Friedrich Schorr’s voice lost its glow. Mr. Janssen rejoices in a mellow instrument not extraordinary in size but rather more extensive in range than is customary in German baritones and easily, if not faultlessly, produced. His conception of the part was along conventional lines and suggested a good deal of previous experience.

Another reviewer remarked that “Mr. Janssen brought breadth of style to his characterization, sang with a voice fresh and resonant and was well received by the audience.”

Of a later performance in the same role, in February 1944, Oscar Thompson wrote that Janssen’s performance was a “highly creditable achievement and one soundly based on the traditions of the past”, but also remarked that his voice was “scarcely heavy enough for the Erda scene”. [Italics added.]

Turning to his performances of the Walküre Wotan, one has the added advantage of two splendid recordings of live performances: the first is the Metropolitan’s own issue of the opera from 1944 and in this performance Janssen is in superb voice and never sounds over-parted. His brilliant high range actually sheds a new light on the music, which is, of course, more usually sung by darker and heavier voices, which emphasize and give weight to the low-lying parts of Wotan’s music. And despite the “lighter” character of his voice, Daniel’s training ensures that even when singing on the same stage and to the same microphones as Helen Traubel, his voice never sounds too small or out of balance.

A later live performance, this time of (a somewhat cut) Act III alone, again with Traubel, but under Rodzinsky, took place in Carnegie Hall in November of 1945. It is a great pity that this performance, in superb sound, is less well-known than the studio recording made with the same forces the previous May after a tiring season and when Janssen was in noticeably less-good voice. Once more the impression on today’s listeners is of a Wotan one would love to hear in a contemporary performance: again, the music is beautifully and feelingly sung.

How did contemporary reviewers find Janssen’s Walküre? Well, Jerome D. Bohm says this, for example:

“Mr. Janssen’s Wotan […] is an impressive delineation, both in song and action, suggesting with plastic gestures the various qualities, noble, tender, and wrathful of the ruler of Walhalla. Some portions of the music lie too low for his high baritone voice to encompass resonantly, but for the most part he sang admirably, often with dramatic intensity, as in the climatic “Das Ende” of the second act narrative, or with touching tenderness in the second half of the ‘Abschied’”.

Of another performance, the same reviewer writes that Janssen’s Wotan “was not only voiced with unfailing tonal sumptuousness and full realization of the many-faceted musical aspects of the role, but ... distinguished dramatically as well.” Olin Downes, too, was impressed, finding Janssen’s Wotan “beautifully sung with all the essential sonority and bigness of line”. Of his Rheingold Wotan, the same critic observed that “the finest singing of the evening was Mr. Janssen’s, and it was paralleled by his histrionic excellence”.

Turning to the other heavy role supposed to have been too much for Janssen, that of Hans Sachs, once again, in a live recording and in the reviews, we find something rather different from the ‘standard’ account. In those early, rather unexpected performances of the role in December 1939, after he had been singing Kothner to great applause, the critics, while acknowledging much beautiful singing, found his characterization not yet fully evolved and wondered if his lyric baritone would ever acquire the power to do the music full justice. By 1945 though, the year from which we have a live performance from the Met, things had changed. Janssen had been working hard at his conception of the role and the critics were now impressed. The distinguished critic, Max de Schauensee, a connoisseur of opera who had a long experience of both European and American performances, gave a glowing review of the whole performance that he heard in January of 1945. Of its Sachs he writes:

Herbert Janssen’s voice may lack some of the weight and depth for the music of Hans Sachs, but his singing is so beautiful in quality, his style so noble and distinguished, just to hear him was a constant pleasure. Mr. Janssen’s interpretation of [Hans Sachs’] character was also a matter of rejoicing. Sachs’ human and affectionate traits were vividly portrayed. The character was never heavy or stale.

By November 1947, Bohm, in the Herald Tribune, wrote that for him,

The most satisfactory aspect was the moving assumption of the role of Hans Sachs by Herbert Janssen. It has taken this distinguished barytone [sic] several years to achieve the complete insight into the many-faceted character attained at this performance. Now he has succeeded in blending the cobbler poet’s manly tenderness, his mordant humor and philosophical resignation into a well-rounded, expressively voiced portrait.

A week later, even Irving Kolodin, who was not usually well-disposed towards Janssen, described Janssen’s Sachs as “vocally magnificent”! And that most thoughtful commentator on the Met broadcasts, Paul Jackson, considered that the previously referred-to broadcast from 1945 was, of the many surviving opera broadcasts with Janssen, the performance which most “fully reveals Janssen’s artistry.” In his wonderfully evocative description of this performance, he begins by saying that “Janssen is an able successor to Schorr” and I do not think that there can be any higher praise than that. Jackson is particularly emphatic about how Janssen’s tone, though unsparingly spent throughout the opera, remains opulent.

One can hope, as we suggested above, that these letters, reviews, and sound documents will provide a more balanced version of Janssen’s venture into heavy roles. From now on, I think, the emphasis should be put on the fact that Janssen described himself as less temperamentally sympathetic towards these roles than he was towards others in his repertoire. No doubt, too, pressure was applied by the Met management to have him sing the heavy roles more often than he would himself have chosen to. But that he himself first, deliberately, and in the teeth of three of his mentors’ advice to the contrary, chose to study and sing Wotan and Sachs, and that he came to do so with critical and popular success and great distinction, these are indisputable facts. None of this, of course, alters the fact that Janssen’s voice did darken with time, but this is unsurprising in a hard-working singer who is approaching the age of sixty.

Turning now to the chronicle of Janssen’s career and its critical reception in the Americas, we can see a further restriction in repertoire, especially in the case of his roles at the Metropolitan Opera. Just as the very large number of roles that he sang in continental Europe was reduced to a much smaller number when he went to Covent Garden, so, when he joined the Metropolitan, his repertoire was reduced even further: apart from a few appearances as the Speaker in Zauberflöte, as Don Fernando in Fidelio, and as Jokanaan in Salome, he was really limited to his Wagnerian roles.

In Buenos Aires, he had a rather wider choice: in addition to his appearances in Wagner, he sang Homonay in Johann Strauss’s Der Zigeunerbaron in 1940 and in the same year the title role in Weinberger’s Svanda Dudak. In 1941, he was back to his role of Papageno in the Zauberflöte, and sang Doktor Falke in Die Fledermaus, a role he greatly enjoyed. In 1943 he sang Don Fernando in Fidelio and Orest in Elektra. But in 1946 and 1947, his last two seasons there, he sang only Wagner.

At the Metropolitan Opera Janssen was esteemed by critics and audiences from the first. Of what was only his second appearance as Wolfram there, in company with Melchior, Branzell, and Jessner, Oscar Thompson wrote:

Lyricism of a kind that never yet made an opera or a music drama less enjoyable played an enlarged part in the beginning of the Metropolitan’s Wagner cycle yesterday afternoon, thanks to the participation of the company’s new German baritone, Herbert Janssen. His beautifully sung Wolfram was an important factor in the success of a sturdy and in many respects admirable, performance of Tannhäuser conducted by Eric Leinsdorf. […] Mr. Janssen treated the several airs of Wolfram much as the highest type of song interpreter might treat Lieder of Schubert or Brahms. That is to say, he sang them with affectionate regard for their poetic feeling as well as their musical qualities. His tone was warm and unforced, his style that of one who knew and respected the uses of legato. Singing so poised, so smooth, so expressive, and of such technical excellence will always be welcomed by the discriminating.

When Janssen first sang the very different role of Telramund at the Metropolitan together with Flagstad and Melchior, the same critic wrote:

…The baritone sang the role with the lyricism that had distinguished his Wolfram in Tannhäuser, but also with the dramatic weight necessary to carry conviction in the charge against Elsa and the long colloquy with Ortrud in the second act. His production remained that of a well-schooled vocalist who has no need to force the tone and who aspires to preserve rather than shatter a melodic line.

As usual, his Gunther was always found “miraculous”, “unusually distinguished” and “vocally admirable”. His Kurvenal, too, was found to be “moving and expressive” and was singled out from time to time as being some of a performance’s “finest, and most touching singing and acting”. Among the roles for which he was so especially admired at Bayreuth, Berlin, or Covent Garden, only his Dutchman seems to have disappointed American audiences, although critics still praised the fine singing. In the Dutchman’s case the reason for this appears to be simply that audiences were used to the role’s being sung by burlier, darker, bass-baritone voices.

As for Parsifal, Noel Straus writes that Janssen “delivered the music of Amfortas with his accustomed richness of tone and keen understanding of the needs of the role” and this reaction recalls Janssen’s European reception as Amfortas. Of Janssen’s Kothner in Meistersinger there was no doubt that it was masterful, Quaintance Eaton finding it a “magnificent portrait, unctuous, condescending, pompous”.

Against those who argue that Janssen’s voice suffered from significant deterioration as the years passed, two last comments about performances from nearer the end of his career may serve as assessments that give us a more balanced picture of critical opinion in his own time and in ours. If the singing of the heavier Wagner roles had really greatly damaged his voice, it is hard to understand how his singing of the lyric role of Wolfram could provoke the following review—almost an echo of Herman Klein’s review of the 1930 Bayreuth recording—from Noel Straus as late as November 1947, when Janssen sang with Torsten Ralf, Thebom, and Varnay:

The most completely satisfying singing was provided by Herbert Janssen, who delivered Wolfram’s music with rich, mellow, finely controlled tones and gave a really distinguished portrayal, one that was both deeply felt and nobly projected. Rarely is Wolfram’s aria at the song contest in the ‘Wartburg’ made as interesting and vital a part of a Tannhäuser performance as Mr. Janssen found possible to achieve with it, and all of his other work was on an equally high plane.

The scrupulous and reflective commentator on the Met broadcasts, Paul Jackson, found Janssen’s 1950 performance of the very demanding role of Telramund, only two years before his retirement, to be, like the previously mentioned Meistersinger, among the very best surviving recordings of his Met career:

Janssen is in marvelous form…. Though his unique qualities are little served by Telramund’s surly grumblings, the fifty-[eight] year-old baritone sings with complete vocal freedom, his top voice (which could be recalcitrant) particularly resplendent. He prefers passion to self-pity, relying on quantity of tone to convey the miscreant’s anger and despair. And there are always those sensitive Janssen moments […] Yet when Telramund must rage, […] Janssen hurls his mighty mix of declamation and sustained tone with unrelenting force.

And in the same year Olin Downes wrote that he was still singing Amfortas “admirably and with feeling”.

In addition to his work for the Metropolitan Opera in New York and elsewhere and his appearances at the Colón opera in Buenos Aires, Janssen took part in a good deal of concert work: we have reports of concerts with Barbirolli, Reiner, Rodzinksy, and Walter, as well as much charity work for causes as diverse as the Met Opera Fund, toys for poor children, Danish relief, animal welfare, and so on. Live recordings exist of a St. Matthew Passion under Walter, as well as of a St. John Passion under Kleiber, a wonderful Brahms Requiem under Toscanini, an Elektra under Mitropoulos and a Fidelio from 1944, also under Toscanini, where Janssen is—rather oddly—cast as Don Pizarro. Reviewing the latter recording in 1956, the very sensitive critic Dyneley Hussey writes: “There is a good Pizarro too, Herbert Janssen, whom it is a pleasure to hear again. The singer must have been near the end of his career when this performance was given but his voice sounds strong and he avoids the snarling villainy which has to make do for malevolent power.”