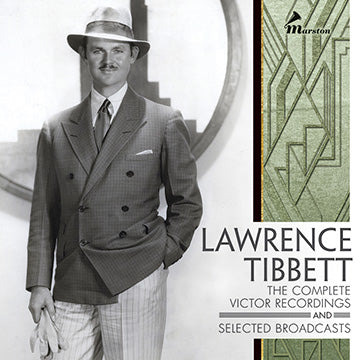

Lawrence Tibbett signed his first contract with the Metropolitan Opera at age twenty-six and over the years built a hugely successful career. His voice was large, deep, and dark-timbred. His dynamic range (in his prime) ranged from forceful fortes to delicate pianissimos. Falstaff’s Ford was his breakthrough role and he was an outstanding Simon Boccanegra, Iago, Scarpia, and Escamillo. Tibbett was the consummate musician with an incredible stage presence. Sadly, arthritis and alcohol took its toll and Tibbett died from a fall in his apartment at age sixty-three.

Tibbett recorded exclusively for RCA Victor between 1925 and 1940, making over one hundred sides. Marston Records is pleased to present the complete Victor recordings of Tibbett for the first time. In addition, this set will include recordings made for his films, Metropolitan and Under Your Spell, as well as selections from his Packard and Chesterfield radio broadcasts never before available on compact disc. The booklet will contain many rare photos and a comprehensive essay by author and critic Conrad Osborne on Tibbett’s life, career, and recorded legacy.

CD 1 (80:27) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio | ||

| 3 March 1926 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon | ||

| 1. | FALSTAFF: È sogno? o realtà? (Verdi) | 4:29 |

| CVE-34930-4 (unpublished on 78rpm) | ||

| 2. | FALSTAFF: È sogno? o realtà? (Verdi) | 4:30 |

| CVE-34930-5 (unpublished on 78rpm) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio | ||

| 24 May 1926 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon | ||

| 3. | Oh That We Two Were Maying, Op. 2, No. 8 (Nevin) | 3:04 |

| BVE-35474-4 (1172) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio | ||

| 7 June 1926 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon | ||

| 4. | Thy Beaming Eyes, Op. 40, No. 3 (MacDowell) | 2:25 |

| BVE-35475-5 (1172) | ||

| 5. | PAGLIACCI: Si può? [Prologue] (Leoncavallo) | 7:25 |

| CVE-35481-3 and CVE-35481-2 (6587) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio | ||

| 30 March 1927 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon | ||

| 6. | Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes (Old English air) | 3:39 |

| BVE-37878-1 (1238) | ||

| 7. | Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms (Old Irish air) | 3:40 |

| BVE-37879-3 (1238) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio | ||

| 31 March 1927 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon | ||

| 8. | Old Black Joe (Foster) | 3:36 |

| with male quartet: Charles W. Harrison, tenor; Lewis James, tenor; Elliott Shaw, baritone; Wilfrid Glenn, bass | ||

| BVE-37880-3 (1265) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 31 May 1927 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 9. | Uncle Ned (Foster) | 3:43 |

| with male Quartet: Charles Hart, tenor; Lambert Murphy, tenor; Royal Dadmun, baritone; James Stanley, bass | ||

| BVE-37881-5 (1265) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 1 June 1927 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon | ||

| 10. | Still wie die Nacht (Calm as the Night) (Götze) | 3:35 |

| with Lucrezia Bori, soprano | ||

| BVE-38854-3 (1747) | ||

| 11. | LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN: Belle nuit, ô nuit d’amour (Fairest Night of Starry Ray) [Barcarolle] (Offenbach) | 2:55 |

| with Lucrezia Bori, soprano | ||

| BVE-38855-3 (1747) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 5 April 1928 | ||

| Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Giulio Setti | ||

| 12. | THE KING’S HENCHMAN: Oh, Caesar, Great Wert Thou (Taylor) | 3:55 |

| CVE-43613-1 (6845) | ||

| 13. | THE KING’S HENCHMAN: Nay, Maccus. Lay him down. (Taylor) | 4:20 |

| CVE-43614-1 (6845) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio | ||

| 10 April 1928 | ||

| Mark Andrews, organ | ||

| 14. | Le Crucifix (The Crucifix) (Faure) | 3:34 |

| with Richard Crooks, tenor | ||

| BVE-43720-1 (unpublished on 78rpm) | ||

Victor Talking Machine Company, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 29 May 1928 | ||

| Stewart Wille, piano | ||

| 15. | Shake Your Brown Feet, Honey (Carpenter) | 2:59 |

| BVE-45187-1 (unpublished on 78rpm) | ||

| 16. | THE PACKET BOAT: Roustabout (Hughes) | 2:58 |

| BVE-45188-1 (unpublished on 78rpm) | ||

| 17. | Travelin’ to de Grave (Spiritual, Arranged by William Reddick) | 1:59 |

| BVE-45189-1 (unpublished on 78rpm) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 3 and 10 April 1929 | ||

| Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Giulio Setti Fausto Cleva, organ | ||

| 18. | TOSCA: Tre sbirri, una carrozza [Te Deum] (Puccini) | 4:28 |

| 3 April 1929; CVE-51116-2 (8124) | ||

| 19. | TOSCA: Tre sbirri, una carrozza [Te Deum] (Puccini) | 4:09 |

| 10 April 1929; CVE-51116-4 (8124) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 8 April 1929 | ||

| Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by Giulio Setti | ||

| 20. | CARMEN: Votre toast [Toreador Song] (Bizet) | 4:40 |

| CVE-51117-4 (8124) | ||

| 21. | CARMEN: Votre toast [Toreador Song] (Bizet) | 4:25 |

| CVE-51117-5 (8124) | ||

| Languages: Tracks 1, 2, 5, 18 and 19 in Italian • Tracks 3, 4, 6–17 in English • Tracks 20 and 21 in French | ||

CD 2 (76:35) | ||

RCA Victor, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio | ||

| 27 and 28 May, 1929 | ||

| THE CRUCIFIXION (Stainer) | ||

| recorded on twelve sides; No. X., Litany of the Passion (hymn) was omitted from the recording. Lawrence Tibbett, baritone; Richard Crooks, tenor Mark Andrews, organ Trinity Choir Sopranos: Lucy Isabelle Marsh; Olive Kline; Della Baker; Ruth Rodgers; Emily Stokes Hager Contraltos: Elsie Baker; Helen Clark; Rose Bryant; Edna Indermaur Tenors: Lambert Murphy; Charles Hart; Lewis James; Charles W. Harrison Baritones and basses: Frank Croxton; Wilfred Glenn; Elliott Shaw; James Stanley; Stanley Baughman conducted by Clifford Cairns | ||

| 1. | I. And They Came to a Place Named Gethsemane (tenor recitative) | 1:05 |

| 27 May 1929; CVE-53735-2 (9424) | ||

| 2. | II. The Agony—Could ye not watch with Me one brief hour (bass solo); And They Laid Their Hands on Him (tenor solo) | 6:24 |

| 27 May 1929; CVE-53735-2 and CVE-53736-1 (9424) | ||

| 3. | III. Processional to Calvary (organ solo); Fling Wide the Gates (chorus; tenor solo) | 9:17 |

| 27 May 1929; CVE-53736-1, CVE-53737-1, and CVE-53738-1 (9424/5) | ||

| 4. | IV. And When They Were Come to the Place Called Calvary (bass recitative) | 1:04 |

| 27 May 1929; CVE-53739-2 (9426) | ||

| 5. | V. The Mystery of the Divine Humiliation—Cross of Jesus, Cross of Sorrow (hymn) | 1:55 |

| 27 May 1929; CVE-53739-2 (9426) | ||

| 6. | VI. He Made Himself of No Reputation (bass recitative) | 1:44 |

| 27 May 1929; CVE-53739-2 (9426) | ||

| 7. | VII. The Majesty of the Divine Humiliation—King Ever Glorious (tenor solo) | 4:30 |

| 27 May 1929; CVE-53740-2 (9426) | ||

| 8. | VIII. And As Moses Lifted Up the Serpent (bass recitative) | 1:14 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53741-2 (9427) | ||

| 9. | IX. God So Loved the World (chorus) | 3:09 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53741-2 (9427) | ||

| 10. | XI. Jesus Said, ‘Father, Forgive Them’ (tenor and male chorus recitative) | 0:46 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53742-1 (9427) | ||

| 11. | XII. So Thou Liftest Thy Divine Petition (tenor and bass duet) | 4:01 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53742-1 (9427) | ||

| 12. | XIII. The Mystery of the Intercession—Jesus, the Crucified, Pleads for Me (hymn) | 1:32 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53743-1 (9428) | ||

| 13. | XIV. And One of the Malefactors (bass solo and male chorus) | 2:06 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53743-1 (9428) | ||

| 14. | XV. The Adoration of the Crucified—I Adore Thee, I Adore Thee! (hymn) | 1:11 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53743-1 (9428) | ||

| 15. | XVI. When Jesus Therefore Saw His Mother (tenor solo and male chorus) | 2:53 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53744-2 (9428) | ||

| 16. | XVII. Is It Nothing to You? (bass solo) | 1:20 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53744-2 and CVE-53745-1 (9428 and 9429) | ||

| 17. | XVIII. The Appeal of the Crucified—From the Throne of His Cross (chorus) | 6:16 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53746-1 (9429) | ||

| 18. | XIX. After This, Jesus Knowing That All Things Were Now Accomplished (tenor and male chorus recitative) | 2:03 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53746-1 (9429) | ||

| 19. | XX. For the Love of Jesus—All for Jesus! All for Jesus! (hymn) | 0:44 |

| 28 May 1929; CVE-53746-1 (9429) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 13 January 1930 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 20. | The Rogue Song (from the film THE ROGUE SONG) (Stothart) | 3:23 |

| BVE-58187-1 (1446) | ||

| 21. | The Narrative (from the film THE ROGUE SONG) (Stothart) | 3:17 |

| BVE-58188-3 (1446) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 15 January 1930 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Rosario Bourdon | ||

| 22. | When I’m Looking At You (from the film THE ROGUE SONG) (Stothart) | 3:47 |

| BVE-58195-2 (1447) | ||

| 23. | The White Dove (from the film THE ROGUE SONG) (Lehár, Arranged by Stothart) | 3:46 |

| BVE-58196-3 (1447) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 15 April 1930 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 24. | UN BALLO IN MASCHERA: Eri tu che macchiavi quell’anima (Verdi) | 4:38 |

| CVE-53454-2 (7353) | ||

| 25. | UN BALLO IN MASCHERA: Eri tu che macchiavi quell’anima (Verdi) | 4:31 |

| CVE-53454-3 (7353) | ||

| Languages: Tracks 1–23 in English • Tracks 24 and 25 in Italian | ||

CD 3 (81:48) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Liederkranz Hall | ||

| 15 April 1930 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 1. | IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: Largo al factotum (Rossini) | 4:30 |

| CVE-59753-1 (7353) | ||

| 2. | IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: Largo al factotum (Rossini) | 4:21 |

| CVE-59753-4 (7353) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 2 | ||

| 6 March 1931 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 3. | Without a Song (from the film THE PRODIGAL) (Youmans) | 3:43 |

| BVE-67492- 2 (1507) | ||

| 4. | Life is a Dream (from the film THE PRODIGAL) (Oscar Straus) | 3:41 |

| BVE-67493-2 (1507) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 2 | ||

| 6 March 1931 | ||

| Stewart Wille, piano | ||

| 5. | Wanting You (from the film NEW MOON) (Romberg) | 2:38 |

| BVE-67494-1 (1506) | ||

| 6. | Lover Come Back to Me (from the film NEW MOON) (Romberg) | 2:57 |

| BVE-67495-1 (1506) | ||

RCA Victor, Hollywood, Studio 2 | ||

| 26, 28, and 29 October 1931 | ||

| Stewart Wille, piano | ||

| 7. | Tramps at Sea (from the film CUBAN LOVE SONG) (Stothart) | 3:05 |

| 26 October 1931; PBVE-68327-3 (1550) | ||

| 8. | Cuban Love Song (from the film CUBAN LOVE SONG) (Stothart) | 3:02 |

| sung in E-flat | ||

| 28 October 1931; PBVE-68328-2 (assigned 1550, but issued only on HMV DA1251) | ||

| 9. | Edward, Op. 1, No. 1 (Loewe) | 4:43 |

| 29 October 1931; PCVE-68333-2 (7486) | ||

RCA Victor, Camden, Studio 2 | ||

| 10 December 1931 | ||

| Stewart Wille, piano | ||

| 10. | Edward, Op. 1, No. 1 (Loewe) | 4:49 |

| CVE-68333-4 (7486) | ||

| 11. | De Glory Road (Wolfe) | 4:48 |

| CVE-68331-3 (7486) | ||

RCA Victor, Camden, Studio 2 | ||

| 10 December 1931 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 12. | Cuban Love Song (from the film CUBAN LOVE SONG (Stothart) | 3:35 |

| Sung in D | ||

| BVE-69068-3 Rerecorded with Tibbett overdubbing a tenor part 12 December 1931; BVE-69071-2 (1550) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 2 | ||

| 8 December 1932 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 13. | The Song Is You (from MUSIC IN THE AIR) (Kern) | 3:06 |

| BS-74653-2 (1612) | ||

| 14. | And Love Was Born (from MUSIC IN THE AIR) (Kern) | 3:28 |

| BS-74656-2 (1612) | ||

| 15. | Pilgrim’s Song, Op. 47, No. 5 (Tchaikovsky) | 4:20 |

| CS-74654-1 (7779) | ||

| 16. | Song of the Flea (Mussorgsky) | 3:46 |

| CS-74655-1 (7779) | ||

| 17. | Song of the Flea (Mussorgsky) | 3:46 |

| CS-74655-2 (7779) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 2 | ||

| 16 December 1932 | ||

| Stewart Wille, piano | ||

| 18. | A Kingdom by the Sea (Somervell) | 4:41 |

| CS-74704-2 (personal record pressed without catalogue number) | ||

| 19. | Ol’ Man River (from SHOW BOAT) (Kern) | 3:36 |

| CS-74705-2 (personal record pressed without catalogue number) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 2 | ||

| 19 January 1934 | ||

| Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, conducted by Wilfrid Pelletier | ||

| 20. | THE MERRY MOUNT: Oh, ’Tis an Earth Defiled (Hanson) | 4:33 |

| CS-81086-1 (7959) | ||

| 21. | EMPEROR JONES: Oh Lord! … Standin’ in de Need of Prayer (Gruenberg) | 4:41 |

| CS-81087-2A (7959) | ||

| Languages: Tracks 1 and 2 sung in Italian • Tracks 3–21 sung in English | ||

CD 4 (80:49) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 1 | ||

| 20 April 1934 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 1. | TANNHÄUSER: Wie Todesahnung Dämmrung deckt die Lande … O du mein holder Abendstern (Wagner) | 4:39 |

| CS-82330-1 (8452) | ||

| 2. | FAUST: O sainte médaille … Avant de quitter ces lieux (Gounod) | 4:41 |

| CS-82331-1 (8452) | ||

| 3. | IN A PERSIAN GARDEN: Myself When Young (Lehmann) | 3:23 |

| BS-82332-1 (1706) | ||

| 4. | None but the Lonely Heart, Op. 6, No. 6 (Tchaikovsky) | 3:23 |

| BS-82333-2 (1706) | ||

RCA Victor, Camden, New Jersey, Church Studio 2 | ||

| 30 April 1934 | ||

| Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski | ||

| 5. | DIE WALKÜRE: Leb’ wohl, du kühnes, herrliches Kind [Wotan’s Farewell] (Wagner) | 16:45 |

| CS-83105-1, CS-83106-1, CS-83107-1, CS-83108-1, CS-83109-1 (8543/5) | ||

THE VOICE OF FIRESTONE | ||

| 18 December 1933 | ||

| orchestra conducted by William Daly | ||

| 6. | Lawrence Tibbett greets his radio audience | 0:36 |

| 7. | SERSE: Ombra mai fu (Handel) | 3:50 |

| 8. | The Hand Organ Man (Wolfe) | 4:06 |

| 9. | Without a Song (from the film THE PRODIGAL) (Youmans) | 2:26 |

| 10. | IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: Largo al factotum (Rossini) | 4:43 |

Selected appearances on The Packard Hour, 1934–1935 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Wilfrid Pelletier | ||

| 2 October 1934 | ||

| 11. | DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG: Was duftet doch der Flieder (The Scent of Elders Flow’ring) (Wagner) | 5:28 |

| 30 October 1934 | ||

| 12. | IL TABARRO: Scorri, fiume eterno! (Puccini) | 4:03 |

| Attributed to 27 November 1934 | ||

| 13. | LA TRAVIATA: Di Provenza il mar (Verdi) | 4:44 |

| Attributed to 18 December 1934 | ||

| 14. | MARTHA: Laßt mich euch fragen [Porter Song] (Flotow) | 2:19 |

| 25 December 1934 | ||

| 15. | Die Allmacht, D.852 (The Omnipotence) (Schubert) | 5:50 |

| Unknown date, likely 1934 | ||

| 16. | LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN: Scintille, diamant (Offenbach) | 2:34 |

| 22 January 1935 | ||

| 17. | FAUST: Vous qui faites l’endormie [Méphistophélès Serenade] (Gounod) | 2:47 |

| 20 February 1935 | ||

| 18. | FALSTAFF: È sogno? o realtà? (Verdi) | 4:30 |

| Languages: Tracks 1 and 5 in German • Tracks 2, 16, and 17 in French • Tracks 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 14, and 15 in English • Tracks 7, 10, 12, 13, and 18 in Italian | ||

CD 5 (81:00) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 2 | ||

| 10 October 1935 | ||

| orchestra conducted by Nathaniel Shilkret | ||

| 1. | Last Night, When We Were Young (Arlen) | 4:05 |

| CS-95370-1 (11877) | ||

| 2. | On the Road to Mandalay (Speaks) | 4:55 |

| CS-95371-1 (11877) | ||

RCA Victor, New York City, Studio 2 | ||

| 14 and 23 October 1935 | ||

| Selections from PORGY AND BESS (Gershwin) | ||

| Helen Jepson, soprano; Lawrence Tibbett, baritone; Trinity Choir, directed by Clifford Cairns; orchestra conducted by Alexander Smallens The two solo sides sung by Helen Jepson, recorded later with Nathaniel Shilkret conducting, are omitted here. | ||

| 3. | Summertime and Crap Game; A Woman is a Sometime Thing | 3:21 |

| with Helen Jepson and chorus | ||

| 14 October 1935; CS-95387-1 (11879) | ||

| 4. | I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’ | 3:10 |

| 23 October 1935; CS-95390-2 (11880) | ||

| 5. | The Buzzard Song | 3:52 |

| 14 October 1935; CS-95389-1 (11878) | ||

| 6. | Bess, You Is My Woman Now | 5:00 |

| with Helen Jepson | ||

| 14 October 1935; CS-95388-1 (11879) | ||

| 7. | It Ain’t Necessarily So | 3:04 |

| 23 October 1935; (11878) | ||

Producers: Ward Marston and Scott Kessler

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston and J. Richard Harris

Photos: Girvice Archer, Gregor Benko, the Metropolitan Opera Archive, the San Francisco Opera Archive, and Lori Tibbett

Booklet Coordinator: Mark S. Stehle

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Preface: Will Crutchfield

Booklet Essay: Conrad L. Osborne

Marston would like to thank Dr. Herman Schornstein and Paul R.Terry for their leadership gifts that allowed us to produce the Lawrence Tibbett release.

Major sponsor: Steve Bauman

Additional sponsors: Anonymous (2), Joseph A. Bartush, John L. Frigo, Cary Frumess, Peter Mallon, William Russell, Frank Self, and Richard A. Williams

Marston would like to thank John Bolig for providing important discographic information.

Marston would like to thank Will Crutchfield for his editorial assistance.

Marston would like to thank Gregor Benko and Jeffrey Miller for lending us records from their collection.

Marston would like to thank Mark Bailey, Director of the Yale Collection of Historical Sound Recordings, for providing digital transfers of primary disc sources for the following tracks: CD 4, track 15; CD 9, tracks 12 and 15–17; and CD 10, tracks 11–13.

Marston would like to thank Kevin Mostyn for providing transcription discs containing the Worcester Festival recordings, CD 6 tracks 7–15.

Marston would like to thank Norman White for providing a digital transfer of CD 6, track 16, taken from a unique test pressing in his collection.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

Marston Records is an historical record label. As such, audio and visual materials are products of their particular times, and may contain offensive language or portray negative stereotypes.

PREFACE

by Will Crutchfield

Early jolts impress themselves on the mind, so it is easy for me to recall my first experience of Lawrence Tibbett. It came through a Victrola LP my father had bought, part of the admirable series through which RCA reminded the world in the 1960s and ’70s of the pre-war glories of its Victor catalogue. What electrified my eleven-year-old imagination was “Edward,” Tibbett’s stunning theatrical rendition of a grisly ballad perfectly calculated to appeal to adolescent male sensibilities at the stage of life when one reads Dracula and The Monkey’s Paw.

I had no idea at the time that I was hearing an ultra-rarity: Victrola had chosen the first take of the Loewe song (on this set as CD 3, Track 9), which appeared on vanishingly few 78-rpm copies, perhaps even pressed unintentionally. Almost all originals have instead the version heard on Track 10, recorded a few weeks later, with some significant differences of text and interpretation. This comparison is just one of the uncountable reasons why it is so valuable to have, for the first time, a comprehensive edition of the recordings of America’s greatest singing actor.

Here, Tibbett’s magnificent Victor series is interspersed with a generous selection of his surviving broadcast performances, and accompanied by nearly a hundred photographs and an all-encompassing essay by Conrad L. Osborne. All these are “must-haves” in their own right. Many of the photos are previously unpublished; quite a few of the broadcasts are gems hitherto unknown even to specialist collectors (do not for any reason miss “Begin the beguine,” a great song you’ll never hear sung better). And the essay, by the author most qualified to attempt such a thing, amounts to a year-by-year biography of the artist, a note-by-note biography of his voice and technique, and a song-by-song biography of his art. You may not agree with everything CLO has to say (he considers the second take of “Edward” an improvement; I remain attached to the one that amazed me so long ago), but you will understand Tibbett’s unique artistry and unique role in American culture as never before.

LAWRENCE TIBBETT: THE MAN, THE VOICE, THE RECORDINGS

by Conrad L. Osborne, ©2022

In February of 1950, when Lawrence Tibbett took on the role that was to mark the end of his operatic career—that of Prince Ivan Khovansky in the Metropolitan Opera Company’s first presentation of Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina—Olin Downes, the chief music critic of the New York Times, praised the English enunciation of several cast members “. . . including that of the greatest male singer among Americans whom the Metropolitan has advanced in the last quarter century, Lawrence Tibbett.” A year earlier, James Hinton Jr., a perceptive critic, had written in Musical America of Tibbett’s Rigoletto that it “. . . brought freshly to mind what a really remarkable singing actor he is . . . his phrasing and his movement were an education in the craft of the stage.” These are only two critics’ opinions, but they would not have met with much challenge then, and, granting some allowance for the inevitable changes in what’s considered compelling in opera’s unique forms of singing and acting, would not meet with much even if extended to cover the seventy-plus years since they were voiced.

Neither review dwelt on the singing itself, and indeed Tibbett, though only in his early fifties, had not been close to his best self with any consistency for some eight or nine seasons, his Baker’s-Dozen years of dominance ending in one of the most poignant sudden declines in operatic history. More of that later. The critical reticence of Downes and Hinton reflects the deference—veneration, even—due to a man who vaulted from rough-hewn beginnings to the pinnacle of High Art, at the same time earning lofty status as a star of the popular culture of his time. Tibbett’s is a triumph-and-tragedy tale of the artist as rugged American individualist, without operatic parallel before or since.

THE LAUNCHING, 1896–1922

Lawrence Mervil Tibbet (the second “t” came later) was born on November 16th, 1896 in Bakersfield, a town along the Kern River in South-central California that had flourished as a farm market hub since the coming of the Southern Pacific Railroad some twenty years earlier, and was just beginning to boom with the discovery of oil in the region. His father, William Edward Tibbet, was of English stock, his mother, Frances Ellen McKenzie Tibbet, of Irish. Lawrence was the youngest of four children. The family was Methodist, of at least moderately strict observance. The Bakersfield of those days was not a peaceful place, and in April of 1903 Lawrence’s father, a Kern County Deputy Sheriff, was killed in what is sometimes labeled as “The Last Big Gun Battle of the Old West” against a locally notorious outlaw. For Lawrence and Frances Ellen, this was obviously a tragic occurrence. But for the future of opera, it was probably for the best. For whereas William Edward was a professionally manly man who administered corporal punishment, belittled his son’s physical underdevelopment, and sneered at his early musical inclinations, Frances Ellen was a contralto church soloist who aspired to a life of greater refinement and encouraged the early signs of unusual vocal and musical gifts in her son. She soon left Bakersfield, and though she struggled to support herself and her family with hotel and rooming-house ventures, by 1910 she had succeeded in settling them all into a life of reasonable stability in the City of Angels.

In the fall of 1911, Larry Tibbett (we’ll adopt the familiar spelling now) enrolled at the Los Angeles Manual Training High School. There, presumably under typical adolescent male peer pressure, he began a regimen of physical training he was to pursue until late in life, gradually turning his body into a strength-and-fitness specimen worthy of the old comic-book and nickel-Western ads. He also entered Manual Arts’ theatre program, which, despite the blue-collar trade orientation of the school, was a good one. His stage talent was immediately apparent (his drama teacher—Maude Howell, who went on to a screenwriting and production career of some standing—took special note of his death scene as Mercutio), and when he sought the leading role in an operetta about Miles Standish, his voice was promising enough to earn him free lessons with the tenor Joseph Dupuy. Dupuy even employed him with his choir at five dollars per week and gave him solo roles in its oratorio performances. It was in his time at Manual Arts that Tibbett also met the young woman who was to become his first wife, Grace Mackay Smith.

Upon high school graduation, Tibbett had no interest in further formal education. He kicked about the Los Angeles stage scene, acting in what seem to have been high-level community theatre productions, singing in church, in musicales, and in operetta of both the Austro-American (Herbert, Friml, Romberg) and English (Gilbert and Sullivan) varieties. In summers, he worked as a ranch hand. Following America’s entry into World War I, he enlisted in the Navy, though the closest he came to combat was a supply voyage to Vladivostok as part of the American intervention in the Russian Civil War. After his discharge in 1919, he married Grace and resumed his struggles in what performers have always recognized as their natural employment milieu, known now as the gig economy, his most remunerative gig being fifteen weeks singing between film showings at Sid Grauman’s Million Dollar Theatre.

In 1921, Tibbett auditioned for a production of The Mikado, in which Basil Ruysdael was to sing the title part. Ruysdael had relocated to Los Angeles after eight seasons in the more important secondary bass roles (e.g., Hunding, Varlaam, The King in Aïda) at the Metropolitan. He took an immediate interest in Tibbett and, like Joseph Dupuy before him, offered him voice lessons gratis, in addition to the role of Pish-Tush. Through another audition for an appearance at a women’s organization, Tibbett also came to the attention of Rupert Hughes, a poet and author of high reputation, and an accomplished musician as well. Over dinner, Hughes urged Tibbett to head for New York, on borrowed money if necessary. It was necessary, and through the good offices of James G. Warren, president of The Orpheus Club, where Tibbett had often sung, sufficient funds were raised to buy the train ticket and allow for a few months’ grubstake. In April of 1922, armed with letters of recommendation from Warren and Ruysdael, and leaving behind his wife and their twin sons, Lawrence Tibbett left for New York and the studio of Frank La Forge.

La Forge was a power on the New York singing scene. He had been the accompanist of several important singers (Farrar, Galli-Curci, Matzenauer, Schumann-Heink) and had become the coach of soprano Frances Alda, the wife of the Metropolitan’s General Manager, Giulio Gatti-Casazza. Alda took the young baritone into her touring Alda-Metropolitan Quartette (replacing Giuseppe de Luca) under the management of Charles Wagner. And it was through the combined efforts of Alda and La Forge that Tibbett secured an audition with Gatti in April of 1923 and, on appeal from Mme., a second hearing that led to a contract for the following season. He made his debut in November 1923 in Boris Godunov as the monk Lovitsky, who sings a few lines in Latin in the Kromy scene. The Boris of the performance was Feodor Chaliapin.

Gatti brought Tibbett along slowly. With Titta Ruffo and Antonio Scotti still on hand, and Giuseppe de Luca, Giuseppe Danise, and Mario Basiola in their prime years, the Met was not hurting in the Italian baritone department, and in the fourteen months between his debut and his legendary breathrough evening as Ford, his best assignments were as the Herald in Lohengrin, Silvio in Pagliacci, and Valentin in Faust, none of which attracted unusual attention, though his first Valentin earned him credibility with the management for making it through the role as a last-minute replacement. The story of the Falstaff of January 2nd, 1925, has been often recited. I think it will suffice here to say that on the opening night of a revival built around Scotti, Tibbett’s singing and acting of Ford’s Monologue, “È sogno? o realtà?”, occasioned a thunderous and prolonged audience response, followed by the sort of press reaction usually afforded a tabloid celebrity. They also led to new management with the rising powerhouse agency of Evans and Salter, and to his first studio session with RCA Victor, for whom he was to record exclusively for the next fifteen years.

At the Brink, 1922–1925

Before beginning consideration of the recordings and Lawrence Tibbett’s rise to stardom, it’s worth pausing to mark the route he has traveled so far, and take note of what is most rewarding to listen for in his voice. He has risen through an ecosystem of operatic education and production that today seems woefully underdeveloped, but which nonetheless produced at least a few grand-opera luminaries of greater stature, vitality, and individuality than we now seem capable of cultivating. He had the benefits of neither a liberal-arts higher education nor more specialized conservatory training. Instead, he plunged by choice into the musical and theatrical milieu around him, into the practice of the skills he sought to perfect, at whatever level he found open to him. He was hungry to learn, but after his clearly constructive high-school years, the learning was by way of self-instruction and private mentorship, with his livelihood on the line and no safety net beneath him. It is often remarked that he was the first American male singer to attain true stardom without European training and experience, preceded by only Rosa Ponselle among American women. That is true, and his self-awareness as an exemplar of American exceptionalism in a field of European high culture, and as a part of the foundation of what he hoped would become an authentically American school of opera, were to become important components of his performing self and of his unprecedented popularity.

In the Tibbett literature one sometimes comes across the notion that his voice was a “constructed”—as opposed to a “natural”—one. I think that this is to confuse matters of musical, linguistic, and stylistic cultivation with the voice itself. As is often the case with a great singer, it is difficult to ascertain just what his technical training encompassed. But the young man who first wins the leading roles in school operettas (quite different from the amplified pop-and-rock musicals of the present, which are minefields for adolescent voices), who gets free lessons and performing opportunities from professionally knowledgeable teachers, who attracts the sponsors of musicales and club recitals and earns the support of wealthy and well-connected patrons, is not someone struggling to find basic attributes of timbre, sonority, and pitch range. They’re already there, though not at full maturity. Tibbett’s first teacher, Dupuy, was a well-respected musician whom Tibbett later described as “an excellent drillmaster in music of this [i.e., the religious] type,” who put his young charge through an exercise regimen (“staccatos, legatos, scales, cadenzas”) that Tibbett admittedly found tedious. His second, Ruysdael, considered by Tibbett the most helpful, hounded him on the matter of well-formed but natural-sounding English pronunciation and, in the manner of a strength-and-fitness coach, addressed bodily weaknesses and tensions. Tibbett later credited Ruysdael with opening up his voice by getting him to relax.

As for La Forge, while it is clear that he was a superior pianist (a pupil of Lechetizky) and a shrewd, ambitious self-promoter, it’s not at all clear that he knew much about the workings of voices. He was never a singer or even a student of singing himself, and I surmise that he deployed his advanced musical knowledge and aesthetically tuned ear, augmented by observations and technical language picked up from the prima donnas he had played for, and presented it all with an air of authority. He seems to have helped Tibbett in the areas of musical expression and stylistic acumen, though much of the woodshedding of repertoire was handed over to a very capable and supportive associate, Helen Moss. For that sort of work to succeed, the voice must already be structurally complete, or nearly so. The exercise patterns Tibbett attributed to La Forge are of a generic sort any teacher might use for warm-ups. Neither they nor the default vowel used (the American diphthong “ay”) are directed toward any specific vocal use. Tibbett didn’t like LaForge personally, and tried other teachers on a couple of occasions, only to return to LaForge because of the latter’s strong connections with managers, critics, and patrons.

All this does not mean that important steps weren’t taken by these mentors in Tibbett’s maturation. But it does strongly suggest that his instrument was more a gift of nature and earliest usage than of “voice-building” pedagogy. His early theatre experience and predilection for acting (to the point of weighing it, and not singing, as his career choice) was also surely a factor. For him, singing was always first and foremost a means of dramatic expression, and the exuberant—at times reckless—energy he directed toward that goal was a component of the voice itself. And what sort of voice was that?

A woman I knew (older than I, but still young) in my apprentice acting seasons used to say that Tibbett’s voice had a “call” in it. She was speaking as a woman, and there’s not much doubt about the erotic appeal of the Tibbett tone, virile and commanding, yet capable of turning tender or romantically nostalgic in an instant. The “call” also has a “Lonesome Cowboy” element, a sound we might imagine hearing from a distance on the Western plains, rock-steady and manly, but with a plaintive tint. I can’t think of a European voice that has quite that sound. Along with that of John Charles Thomas, it is the top-of-line exemplar of what was in those times the American baritone identity, reflected in the timbres of Nelson Eddy and many of the “legit” baritones who displaced the operetta tenors in the leading roles of Broadway musicals. It wasn’t a massive voice. Ruffo, in Tibbett’s early years, and Alexander Sved, later, were both deemed “bigger” baritones, and there are even references to Tibbett’s sound during his first seasons as an essentially “light” one. His leaner instrument came to qualify as a “dramatic” baritone by virtue of its core and thrust and his authoritative, dramatically heightened delivery.

We will encounter many opportunities for discussion of technical specifics as we consider the individual recordings. For the moment, let it be observed that the qualities described above were deployed in performance over a pitch range of slightly more than two octaves—from the G an octave and a fourth below the middle C to the A-natural in the octave above it. This in itself is not common among great operatic baritones, who have often been limited at the lower end of the range—singers of such high accomplishment as Mattia Battistini, Heinrich Schlusnus, and Ruffo himself can be cited in this regard, and the notable exceptions have been among baritones of much “looser” overall structure, as in the otherwise dissimilar cases of Cornell MacNeil and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Tibbett’s voice also embraced the full continuum of dynamic shadings, from softer ones that were (almost) never of the crooned variety to louder ones that clearly impinged, even when not of overwhelming weight. And it showed a color span reflexively responsive to the expressive demands placed upon it by the singer’s active dramatic imagination.

There is one aspect of Tibbett’s technique, sometimes mentioned as a contributing factor to his vocal crisis, that will be interesting to listen for as we move through his recorded legacy. In the uppermost segment of the chest register (B to E-natural), his singing of the open vowels (“a” and “e”) at forte can sound “too open,” too driven, and lose the easy, consistent vibrato elsewhere evident, taking on a fixed or, in rare instances, deadened quality and necessitating an overly precipitous shift into the more gathered focus required for the high range. At other moments, the darkening of timbre in that same area of range (suggestive of what some Italian teachers and singers termed “the vuoto” i.e., “empty” or “hollow”—an adjustment attributed only to baritone voices) can at moments sound imposed on the instrument, rather than natural to it. That this is not entirely a question of “open” versus “closed” or “covered” is shown by the example of de Luca, who sometimes sang F-natural or even F-sharp in an “open” manner, yet without any loss of vibrato, timbral beauty, or liquid flow, or in a different way by that of Thomas, who on occasion attacked those same pitches in what singers would call a “wide open” fashion, yet got away with it. With Tibbett, it sounds more like a stiffening in his positional hold on the tone that inhibits a completely free emission. I’ll try to evaluate these symptoms, along with that of a slight overall darkening and some loss of brilliance (though not of reach) at the top, as an element in the voice’s crisis when we arrive at that sad juncture. For now, on to the recordings of Lawrence Tibbett in his youth and glorious prime.

Worth noting: Tibbett’s recording career began at the electrical method’s crack of dawn. The studio orchestras assembled to take advantage of the new technique, customarily under the direction of Rosario Bourdon or Nathaniel Shilkret, must have sounded splendid—at least at first—to listeners accustomed to the acoustical method, but inevitably seem undernourished to our ears. In terms of arrangement and execution, their work ranges downward from pickup-pro-acceptable to less than that, and I won’t comment about them further except for anomalies and exceptions.

THE ASCENT, 1925–1929

Verdi/Shakespeare/Boïto: FALSTAFF: È sogno? o realtà? (unpublished, takes 4 and 5, 3 March 1926) (CD 1/1-2). The first of Tibbett’s recordings to be assigned matrix numbers (there had been trial sides a year earlier, two of them self-accompanied) was, unsurprisingly, of the piece that had earned him his initial triumph, Ford’s great monologue. And we immediately encounter, in rather extreme form, the very technical issue I have just described. To be sure, the voice’s characteristic timbre and steadiness are already present, and as the singer rides powerfully up to a ringing G-flat at “Due rami enormi crescon sulla mia tes-TA,” we feel we’re in for a spine-tingling ride. Subsequently, though, syllables on the F at the upper edge of the passaggio are given raw, worrisomely open treatment (“il tuo LET-to,” “donna, de-MO-nio,” “NON mia moglie a se stessa”), and we don’t feel that he retakes the reins until the climactic G of “nel fondo del mio COR.” Interpretively, too, his penchant for the dramatic accent exposes immaturities, in the form of exaggerated colorings and a habit of shouting on accented syllables for effect. All this goes on despite Tullio Serafin’s personal coaching on the role throughout the rehearsal period. And we might note that, at least at the outset, Tibbett didn’t know Italian (or French or German, for that matter). He learned his roles by rote, phonetically (though always aware of meaning), and it took time for his treatment of word-setting to take on greater fluency. Of the two takes heard here, the fifth shows some negligible improvements on the fourth.

Ethelbert W. Nevin/Charles Kingsley: Oh That We Two Were Maying, Op. 2, No. 8 and Edward Macdowell/William Henry Gardner: Thy Beaming Eyes, Op. 40, No. 3 (24 May 1926) (CD 1/3–4). We next meet Tibbett in two examples of a type of song he (and many other singers of the time) often included on his recital programs. These are light expressions of genteel romantic sentiment, considerate enough in terms of vocal range and complexity of accompaniment to be essayed by amateur musicians at their parlor pianos, and thus apt to generate satisfying sheet music sales. This is also our first opportunity to assess the aspect of Tibbett’s singing that Ruysdael had so emphasized—his way with an American variant of the English language, which is a remarkable amalgam of unquestionably formal structure (fully formed vowels, exactitude of articulation) with a bonding to the musical line that sounds utterly unaffected. Occasionally, in softer passages, the clarity of word (not of tone) takes on a slight haziness, but the expressiveness of phrase is always present, so that we never lose emotional contact. The setting by Nevins (composer of the once-popular “The Rosary” and “Mighty Lak’ a Rose”) of the Reverend Kingsley’s verses is a purely lyrical expression of midrange legato, dependent on sustainment of breath and precision of intonation. To my ear, Tibbett sings it perfectly. In “Thy Beaming Eyes,” by the better-remembered Macdowell, he shows something we’ll hear frequently from him—the ability to move the voice on the instant from an assertive forte to a melting piano, including a heart-catching attack on the upper E-natural. It’s not quite the subito piano of the old Italians, but it’s based on the same principle of pinpoint control of the swell-and-diminish, and gives no hint of a technical trick for its own sake.

Ruggiero Leoncavallo: PAGLIACCI: Si può? [Prologue] (7 June 1926) (CD 1/5). A year and a half after his breakthrough performances as Ford, Tibbett was still singing secondary roles at the Met, including some very minor ones indeed (the Marquis d’Obigny in La Traviata is barely above the anonymous servant’s announcement of “La cena è pronta” at Flora’s Act 2 party). He had attracted favorable attention as Ramiro in Ravel’s L’Heure Espagnole, but though the part is a romantic male lead in a charming opera, it hardly constituted a principal assignment in a repertory work. However, in January of 1926, he succeeded Ruffo as Neri in Giordano’s La cena delle beffe and registered a major success with an intensely sung and acted performance. On the company’s spring tour of that year, he was given several new important roles to try out. One of them was Tonio in Pagliacci, and it was with his recording of the Prologue in June 1926 that Tibbett announced himself to the world of collectors as an important operatic baritone. Indeed, for the effortless glide of tone that is potent yet suave through the whole range of the piece, including a blandishing mezza voce at “Un nido di memorie” and brilliant acuti at the close, it has few rivals. (For the first of many examples of Tibbett’s unsurpassed respiratory poise, follow the whole slow, legato chain: “Un nido di memorie/in fondo all’anima/cantava un giorno”—not a ripple on the surface of the tone, a flicker in its vibrato, or the slightest deviation from center in its intonation, and without even a well-disguised intake of breath at either of the perfectly permissible points before the end. The polished ease is deceptive.) The fact that this seems to have been the first electrical recording of the aria to hit the market, and that it was complete with the full orchestral introduction (requiring two sides for the original release) were also probably factors in the disc’s huge popularity in both the U.S. and Italy. In contrast to the “È sogno?”, it is, stylistically, a remarkably well-behaved rendition. At spots that could easily succumb to the shouting-for-emphasis syndrome (e.g., “Le lagrime che noi versiam son FAL-se”, or “vedrete dell’odio i TRIS-ti frutti”), Tibbett sticks to singing. A few of those upper-midrange vowels can still be called open-ish (“io sono il PRO-logo;” “in parte ei vuol riprende-RE”), but they are more reconciled toward a gathered, though certainly not “covered,” adjustment. Tibbett snaps off the crush notes on “mette l’autore” and “squarcio di vita” with good bite. Two quibbles: throughout, his “i” vowel cheats toward “ih,” and the release of the exciting high A-flat of “al pari di VO-I” is not completely clean. The royalties from this recording constituted Tibbett’s first big payday.

Ben Jonson (from an Old English air): Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes; and Thomas Moore (from an Old Irish air, My Lodging Is On the Cold Ground): Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms (CD 1/6–7). Despite the critical and financial success of the Pagliacci disc and his growing stature at the Metropolitan, it was to be three years before Tibbett recorded another standard-repertory aria. Instead, Victor kept his Red Seal identity alive with releases that appealed to the American market for his English-language recital songs. Two new varieties were introduced: concert ballads derived from English or Irish folk melodies, and Stephen Foster’s melodious evocations of Southern American (often African-American) sentiment. The ubiquity of these settings in both genres, and the affection with which they were held in millions of American households, is perhaps difficult to appreciate today, as is the thought of their regular appearance on the concert programs of prominent classical singers, except as a self-conscious retro gesture. There is a reason, though: when honestly felt and impeccably sung, as here, they are fragrant and touching. In Tibbett’s rendition of Ben Jonson’s “Drink to Me Only with Thine Eyes”, the firmly declared pledge of the first verse is followed by more of the same sorcery in the softly voiced second. Hear how the portamento carves perfect arcs of sound leading into the reluctantly relinquished final “of thee.” In the setting of “Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms” by Thomas Moore (who also gave us “The Harp That Once Through Tara’s Halls,” “The Last Rose of Summer,” “Oft In The Stilly Night,” and much else in a full and varied life), we might feel that a couple of the soft D-naturals on open vowels in the first verse are not unequivocally positioned, but the singing is otherwise spotless, and the intoning of “As the sunflower turns,” etc., through to the finish of the song is magical.

Stephen Collins Foster, arranged by Rosario Bourdon: Old Black Joe and Foster/N. Clifford Page: Uncle Ned, with the Shannon Quartet (31 March 1927) (CD 1/8–9). In these two Foster songs, Tibbett begins to explore the alternate racial identity that soon became a trademark. In the present examples, though, he does not traffic in dialect. “Old Black Joe” is sung with mainstream formal American (i.e., white) pronunciation (“I’m coming,” not “Ah’s a-comin’,” etc.), and richly vocalized. In “Uncle Ned,” he doesn’t avoid “dere’s” for “there’s,” but otherwise takes on no accent. In Bourdon’s tinkling arrangements, he is joined by a backup quartet, and while we might prefer to simply listen to Tibbett, it’s a good group of its kind, giving us a notion of the “gentle voices calling” in the second verse of “Old Black Joe,” and the deep bass of Wilfrid Glenn making a fine effect at the end of the song. I would again point to the discomfort of an open vowel (the “e” of “Ned”) on the D-natural when sung softly, not because it much affects the lovely effect of the singing, but because we’re tracking Tibbett’s handling of his voice in this tessitura.

Karl Götze, translation by Nathan Haskell Dole: Calm as the Night and Jacques Offenbach/Jules Barbier: LES CONTES D’HOFFMANN: Fairest Night of Starry Ray [Barcarolle], both with Lucrezia Bori, soprano (1 June 1927) (CD 1/10–11). It is a shame that Victor’s pairing of Tibbett with Lucrezia Bori did not yield more than the two items presented here (and that their only Met broadcast outing together was to be in Deems Taylor’s Peter Ibbetson). While the soprano/baritone distribution does not achieve the almost uncanny unity of the soprano/contralto one of Alma Gluck and Louise Homer in similar material, there is a comparable naturalness in the matchup of pure, centered tone, even vibrato, and subtlety of expression, with the added piquancy of a male/female exchange between singers of notable charm. In the English translation of Karl Götze’s “Still wie die Nacht”, the tossing back and forth of brief responses has the effect of what we might term soulful repartée (and note Bori’s touches of light chest voice at spots like “sighing . . . DY-ing,” making a bewitching effect without any overt dramatization). In Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, Tibbett drew attention in his early seasons in the short character part of Schlemil, and was to essay first Dappertutto and then all four of the villains in succeeding seasons. Here, we have an arrangement of the Barcarolle as removed from the opera and its vocal distribution, as were the arias of Handel in those years, and again sung in translation. Even so, the weave of these two voices is elegantly seductive.

Deems Taylor/Edna St. Vincent Millay: THE KING’S HENCHMAN: Oh, Caesar, Great Wert Thou and Nay, Maccus. Lay him down., with the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus, Giulio Setti, conductor (5 April 1928) (CD 1/12–13). In the season of 1926–1927, the Met staged the first in the series of six operas by American composers in which Tibbett, with his resources of voice, dramatic flair, superb elocution, and missionary dedication to the cause of a native repertory, had notable successes. This was The King’s Henchman, with music by Deems Taylor and a libretto by Edna St. Vincent Millay, then at the height of her celebrity as poet, playwright, and exemplar of an independent female Bohemian lifestyle. A year later, Tibbett recorded two selections from the work, now backed for the first time by the Met’s orchestra and chorus. The first, “O Caesar, Great Wert Thou,” is a lively ballad which in the opera is started not by Tibbett’s character, King Eadgar, but by Maccus, a servant and minstrel (sung in the Met production by the bass William Gustafson, who occupied much the same position in the company as Ruysdael had a decade earlier), with the succeeding two verses taken jointly by Tibbett and the tenor Edward Johnson as Aethelwold, and modulating upward accordingly. It jogs along in a “rollicking” style almost like a sea chantey’s, and is engaging enough until Taylor feebly attempts to nail it down with the orchestra at the close. Tibbett, taking the solos of all three verses, sings it brilliantly. In the second, “Nay, Maccus, Lay Him Down,” which begins the opera’s finale, Eadgar bids the assembled lords and ladies of the court to “weep not” for the death of Aethelwold, but to save their tears “for a little sorrow.” According to Thomas Bullard (see bibliography), some part of this passage was slated for redaction until Millay heard Tibbett’s voicing of her words in rehearsal and insisted on its retention. Here he adds to his full-voiced kingly commands several phrases of piano singing of captivatingly mournful and dedicatory tone. In this number the choral writing is better laid-out, and one can imagine a moment of impressive gravity in the theatre.

Jean-Baptiste Faure/F.W. Rosier: Le Crucifix (The Crucifix), with Richard Crooks, tenor (unpublished, 10 April 1928) (CD 1/14). As we have already noted with respect to Tibbett’s study with Joseph Dupuy, church music played an important part in his early musical and vocal development. It did so for many American singers of his day (as did the traditional music of the synagogue for Jewish male vocalists), both for its orientation to classical music models before the introduction of amplification and for its direct connection to the world of oratorio performance, then far more significant as artistic experience and employment opportunity than it is now. Once his opera, film, and concert career was in full flight, Tibbett did not have much occasion to sing sacred music, but he continued to hold it in high regard. In this English-language version of “Le Crucifix,” one of the several selections by the great French baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure that became church solo and recording studio favorites, he is partnered by Richard Crooks. Both singers are in fresh estate, and both bring to the graceful melody (as Tibbett said of his approach toward this repertoire) “the same vital expression and the same intense interest that I would to an operatic role,” with Crooks flinging out a full-throated high B at the close. Listen to the way both artists—but to greater effect in Tibbett’s voice—use the sounding consonants (like the m’s and n’s of “Come unto him”) to bind the line, with absolute maintenance of both legato and sonority. And just think, as you listen to this duet arrangement with its organ accompaniment: if you’d been a congregant of the North Avenue Presbyterian Church in New Rochelle, New York for a time in 1922–3, these would have been your tenor and baritone Sunday soloists, quite possibly in this very number.

John Alden Carpenter/Langston Hughes: Shake Your Brown Feet, Honey; Rupert Hughes/Berton Braley: THE PACKET BOAT: Roustabout; Spiritual, arranged by

William Reddick: Travelin’ to De Grave (unpublished, 29 May 1928) (CD 1/15–17). With these three selections, we are back to the sort of folkish (that is, folk-derived, but composed or arranged) songs that Tibbett regularly programmed. “Shake Your Brown Feet, Honey” is from the set of Four Negro Songs (1927) set to poems of Hughes by Carpenter, whose best-known larger work, the ballet Skyscrapers, had been presented by the Met in 1924. This song can be rendered as a simple, gently swinging up-tempo tune with little variation among the sections. Tibbett starts it that way, but then makes something much more of it—a minidrama about keeping spirits up in the shadow of uncertainty, ending with an ascending piano phrase that seems to melt into air on the concluding upper E of “Sun’s going down this evening/Might never rise no mo’.” This side introduces us to Tibbett’s career-long recital partner Stewart Wille, whose subtle understanding of the uses of rubato and touch contribute much to the artistic finish of the effect, as it will on many subsequent occasions. Roustabout, with music by Tibbett’s patron Rupert Hughes and lyrics by the popular poet and magazine writer Berton Braley, is one of the baritone’s least attractive records, and one of a sub-genre we will meet several more times. A mediocre would-be workingman’s song, it leads Tibbett into a combination of faux-tough straight tone and the sort of snarling that disfigured his early “È sogno?” Only a gifted interpreter with a fine voice could commit these depredations, but they are depredations nonetheless. Happily for us, he is back in his comfort zone with the infectious spiritual “I’m Travelin’ to de Grave”, a trip along life’s final stretch of road that is undertaken in the highest of spirits, since its destination is the eternal Jerusalem. It’s intriguing to realize that of all the race-or-class “character voices” that Tibbett assumed in his lighter recital repertoire, this amalgam of Euro-American with African-American cultural expression is invariably the most natural and spontaneous-sounding. And, since we’re tracking his adventures with the passaggio pitches, we also note that his handling of the repeated E-naturals, both at full voice on a closed vowel (“GLO-ry Hallelujah!) and more crucially at a more restrained intensity on the problematic American “a” as in “land” (“the LAST thing that he said to me”) could not be more adept.

Georges Bizet/Henri Meilhac/Ludovic Halévy: CARMEN: Votre toast [Toreador Song] (takes 4 and 5, 8 April 1929) (CD 1/20–21); and Giacomo Puccini/Luigi Illica: LA TOSCA: Tre sbirri, una carrozza [Te deum] (takes 2 and 4, 3 and 10 April 1929 (CD 1/18–19). RCA Victor returned Tibbett to the standard repertory with a sure-fire pairing of the next two sides, now accompanied by a reduced complement of the Met’s orchestra and chorus under Giulio Setti, and presenting excerpts from two roles in which his onstage encounters with the glamourous and combative Maria Jeritza were fought to a draw. He had introduced Escamillo into his repertory as early as 1924, but though its music sat comfortably in his voice (as it does not for many a good baritone, particularly at the bottom) and its element of bravado seems tailor-made for his temperament, it did not actually become one of his more frequent assignments. He sang the “Toreador Song” often, though, in the course of his radio and film work, and it was an obvious choice from a marketing point of view. The voice here is burnished and bold, the swagger easily conveyed. In terms of linguistic and stylistic elegance, his version will not be confused with that of the best French baritones; but then, how many of them have Tibbett’s virile glamour of tone and manner? On the passaggio trail: the E-flats of “ils ONT les combats” are “too open” both vocally and linguistically, while the repeated E-naturals (“te re-GARDE,” etc., are quite suavely “covered.” Of the two takes, the second is marginally better than the first with respect to details of voice and language.

Scarpia was at this point a new role for Tibbett—he had first sung it only the previous fall in San Francisco. It was one of a couple in which connoisseurs at first compared his interpretation unfavorably with that of Scotti, and it is likely that in terms of elegance of manner, and surely of subtle pointings of pronuncia, they weren’t altogether wrong. As with Tibbett and his French counterparts in Carmen, though, it is difficult to reconstruct even a prime-time Scotti bringing to bear on this part the flood-tide of voice that we hear in Tibbett’s Te Deum. Unlike Escamillo, Scarpia became a standard role for Tibbett, and one that he continued to sing with some success in the later stage of his career. Here the superiority of the second take over the first is decided, with respect to both the positioning of the solo voice, chorus, orchestra, and organ in relation to one another, and Tibbett’s still powerful but more contained singing. For those who enjoy micro-observations: compare between the takes the baritone’s treatment of the vowel “e” on E-flat at “tendo il vo-LER;” the transition from “è la più preziosa” to “Ah, di quegl’occhi;” and the vowel “o” on the last syllable of “capestro.” These are among the tiny things, yielded up by close listening, that become cumulatively significant in terms of both performance effect and vocal efficiency. Tibbett self-corrected these in real time, on the day. On organ, that’s Fausto Cleva, later to be a repertory mainstay on the Met podium.

John Stainer/W.J. Sparrow Simpson: THE CRUCIFIXION (27–28 May 1929) (CD 2/1–19). With Richard Crooks, tenor, Mark Andrews, organ, and the Trinity Choir, Clifford Cairns, conductor. It is hard to make a very strong claim for John Stainer’s oratorio The Crucifixion, either in the light of its conscious model, Bach’s Passions, or in that of the English sacred choral tradition of which it is a distinctly minor example. Between the Victorian sentimentality of the good Rev. W.J. Sparrow Simpson’s libretto and the only occasionally relieved conventionality of Stainer’s musical response, even the sympathetic listener is taxed to sustain engagement. But if one measures it against its intention—to provide an Eastertide piece within the capabilities of at least the better parish choirs (and perhaps a couple of imported soloists), in which the congregation could periodically join for some sturdy hymn-singing—it must be conceded that it’s done with some skill. Besides, one can’t argue with success, and from the moment of its premiere (1887, Marylebone Parish Church, London) it became an anticipated annual event for several decades in churches throughout the English-speaking world. Despite the decline of the tradition it represents, it still surfaces from time to time, and has received several modern recordings. Since the piece was virtually complete on its original release, we are presenting it thus here.

The aforementioned tradition was very much alive here in the U.S. in 1929, when RCA Victor recorded The Crucifixion, complete except for some verses of the hymns, and with the old Sunday morning partners, Tibbett and Crooks, as the principal soloists. Beyond the obvious asset of a world-class voice, Tibbett brings to this music two great advantages. One is that his voice, though invested with a depth and penumbral timbre that eloquently fulfills the modest requirements of the bass-oriented moments in the writing, is truly a technically complete baritone, and so capable of both stirring forte preachments and ravishing mezza-voce disclosures at the high end, where basses do not find the going so easy. The second is Tibbett’s unfailing directness and simplicity of address, which makes his singing reverential without being pious, and dramatic without being theatrical. Despite the thinness of the musical material and the rather confusing shifting back and forth between narration and characterization, the nobility of his vocal presence captures the tone of mystery and tragedy that Stainer was trying to evoke. And there is no fall-off in quality with the contributions of Crooks; he shares with Tibbett a beauty of tone, a seamless passage between a melting piano and a manly forte, and a crystal-clear, supremely eloquent command of the text. The choir is made up of sturdy RCA studio regulars, here labeled “The Trinity Choir.” At a few points in the hymns, we miss the broader, cushioned and blended sound of a good choir (and congregation) that greater numbers might have captured, even with the recording capacities of the time. Nonetheless, it’s a very strong, well-balanced group. They launch willingly into the comically jaunty “Fling Wide the Gates,” and the oratorio’s most famous passage, “God So Loved the World,” comes off well enough. The solo assignments from the chorus (most prominently Wilfrid Glenn as The High Priest) are characterful. As unimaginative as the organ setting for the most part is, it is solidly rendered by Mark Andrews. At this remove, it is touching to hear two great artists and highly professional supporting forces bringing such sincere commitment to the often almost childlike mode of expression of this once-beloved work.

THE GLORY YEARS, 1929–1940

By the time of these sessions at the conclusion of the 1928–1929 season, Lawrence Tibbett could consider himself firmly established. After a highly successful fall season in San Francisco in several major roles (making a special impression as Amonasro), he earned another triumph at the Met in a contemporary one. Following its smash-hit debut (Leipzig, February 1927), Ernst Krenek’s Jonny Spielt Auf had run like wildfire through the German and Austrian houses, and earned its composer several pots of gold. Now it had come to the Met. It told the story of a love affair between a white woman and a Negro (to use the then-preferred term) band leader, and its music combined harmonically traditional, atonal, and jazz elements. As with La cena delle beffe, Tibbett had followed a European star in the title role (Michael Bohnen, prodigious of bass-baritone voice, body, and theatricality), and had more than held his own with a combination of brilliant singing, deft acting, and, in this instance, his aforementioned identification with African-American idiom. His Jonny thus melded with a persona already becoming familiar on his recital tours, and soon to find its ultimate expression in the Gruenberg/O’Neill The Emperor Jones. He had also been busy with standard-repertory roles, having added his first Wolframs in the preceding season, and now two new ones—Marcello and (on tour) Germont. The great Ruffo was gone, and Scotti had narrowed his repertoire to a handful of specialties. If Lawrence Tibbett was not quite yet the leading baritone of the Metropolitan Opera, he was on close to equal footing with de Luca, Basiola, and Danise, and building a relationship with American audiences that even the greatest and most-beloved of European artists could not.

With his departure for a Hollywood screen test in the spring of 1929, Tibbett’s career was about to enter a new phase. His personal life, too, was undergoing changes. It had become clear that his marriage with Grace Mackay Smith was a serious mismatch. She was a strong-minded person with ambitions (and some small success) as a poet, maintaining the couple’s Los Angeles home and raising their now-nine-year-old twins. She had neither much taste for sophisticated New York high life nor the skills for navigating it. Larry, on the other hand, was gregarious, liked by all who knew him on a social and professional level. He reveled in the adulation that was becoming his expected portion, all the more dizzying to an energetic young man sprung from humble circumstances into the milieu of the upper-crust 1920s. He formed relationships, including romantic ones, easily, but was not given to maintaining them well when they moved into deeper territory. In 1927, he had begun an on-and-off affair with Jane Marston Burgard, a socialite to the manor born, then approaching the end of a second well-off but otherwise unrewarding marriage. In time, she was to become Tibbett’s second wife. Meanwhile, his first marriage teetered along at the edge of estrangement, and the already heady pace of his life quickened.

• • • • •

Tibbett’s screen test, set up by Ida Koverman at Louis B. Mayer’s MGM, was successful. He was cast in the male lead in the first of his four films, to be shot over the summer of 1929. This was The Rogue Song, an unrecognizable Hollywoodization of Franz Lehár’s Zigeunerliebe. Tibbett’s director was Lionel Barrymore, his co-star Catherine Dale Owen. Laurel and Hardy chipped in with some comic bits written in after filming was underway. Rogue Song was the first talkie in Technicolor, the first in which an opera star sang onscreen, and the first in the genre of Hollywood operetta movies later taken over by the Jeanette MacDonald/Nelson Eddy combo. A lavish, exotic bandit-of-the-steppes adventure, it’s essentially a lost film, though a few fragments, including the trailer, have been reclaimed, along with a complete soundtrack. This last is from Vitaphone discs recorded after the shoot for possible use with a silent version of the film, and is in excellent sound for its age. (The sound-to-film process was not yet far enough advanced to allow a separately recorded track to be synched with the action. Thus, Tibbett sang everything, including all re-takes—live, in full voice—while filming, and apparently sang at will or on request during down time on the lot as well, besides making other appearances while in the Los Angeles area. Not for the last time, we get a picture of a man with a strong belief in his invincibility.)

Herbert Stothart/Clifford Grey: THE ROGUE SONG: The Rogue Song (13 January 1930); The Narrative (13 January 1930); When I’m Looking at You (15 January 1930); and The White Dove (15 January 1930) (CD 2/20–23). A touch of culture shock, perhaps, as we move from the 19th-Century Anglican pieties of The Crucifixion to the free-spirit notions of movieland, c.1929. These four excerpts from The Rogue Song were timed for the movie’s release. Three of them are by Herbert Stothart, composer of many a Hollywood soundtrack and a few pop hits. They bear traces of acquaintance with the Viennese operetta mode, but are well below the quality of such American practitioners of the genre as Herbert, Friml, or Romberg. The title song is a lusty-outlaw proclamation, of no musical consequence except insofar as it is well-set to exploit the range and power of Tibbett’s voice. He obliges enthusiastically, mastering the high tessitura with fully seated tone and extraordinary crescendos on the top F and G. The second, also known as “The Song of the Shirt,” is just as negligible, though it contains some spoken narration and several examples of the hyperhearty laugh with which lusty outlaws of the time greeted all dangers, ironic discoveries, or initially disinclined women, at least in the movies. Snugly tailored to Tibbett’s romantic wooing mode is the pleasantly lilting “When I’m Looking at You,” made memorable for its stunning diminuendos on the top F, especially the second time around. With “The White Dove,” we are given the group’s one direct adaptation of a Lehár waltz song (complete with “hesitation”), and a very nice one, appropriately translated and transposed. Tibbett gives it the full treatment we’d expect from a Richard Tauber morphed into an American baritone. He received an Academy Award nomination for Rogue Song.

Verdi/Antonio Somma: UN BALLO IN MASCHERA: Eri tu che macchiavi quell’anima (takes 2 and 3, 15 April 1930) (CD 2/24–25), and Gioacchino Rossini/Cesare Sterbini: IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: Largo al factotum (15 April 1930) (CD 3/1–2). Next on Tibbett’s growing Victor list was another pairing of ever-popular arias. He had sung “Eri tu” from his earliest full-grown days, including for his first Met audition (cracking on the high G, which no doubt necessitated the second), and he frequently programmed it on his recitals. But Renato is one of several Verdi parts, along with Di Luna and Rodrigo, to which he would have been well suited but which he never sang. Here is Tibbett assuming full command of his Verdi baritone identity. Except for a subtle use of aspirates to outline pitches at some spots (perhaps not detectable at the distance of live performance but, if we’re being fussy, a stylistic demerit), there is not a thing wrong with either of these renditions. There are interesting differences between them, though. On the first take, the high G at “bril-LA-va d’amor” has a full-throated bloom that is more contained on the second, as well as a more deeply inscribed bite on the G-flat of “Non SIE-de che l’odio,” etc. (He nails it down by leaning into the “i” of the compound vowel: “SI-ede.”) On the second take, though, there are several astonishments absent from the first. In an instance of poise on the breath comparable to the phrase I noted in the Pagliacci Prologue, Tibbett carries through “D’un amplesso che l’essere india” without a break, and with some extra sheen on the F at the top of the phrase’s arc. The E at “de-LI-zia” is ever so slightly more mellifluous, the two syllables on F at “che compensi in tal gui-I-SA” (carrying the “i” vowel up into the F before adding the final syllable) just a mite more smoothly joined, the diminuendo and downward portamento at “vedo-VO-O cor” even more longingly suspended. Most noteworthy, though, is the attack on the F of “O speranze” (at mezza-voce, then diminuendoed), with the phrase again carried on through (and a little catch in the throat after the turn into the D of “d’a-a-a-amor”) on a single breath. From Pasquale Amato’s to Leonard Warren’s, there are many wonderful renditions of this great aria. But this can stand with the best.

I think we can say that in his rendition of “Largo al factotum,” Tibbett’s exhilarating athleticism and seemingly bottomless well of energy carry all before them, the “all” being the rushed quality of the whole, which doesn’t give him room to finish one statement before plunging into the next, and which also contributes to the sketchiness of a couple of the patter passages. The overall impression, in fact, is that of a bold, splashy sketch of a fully developed interpretation. The latter had scant opportunity to emerge, for Tibbett sang only a single performance as Figaro, and that in San Francisco in the fall of 1941, shortly after the period of rest following his vocal crisis. (He was scheduled for the part later that season at the Met, but an attack of appendicitis forced him to cancel.) An attempt, involving several takes, to record Tibbett and Amelita Galli-Curci in the Act 2 Rosina/Figaro scene (along with the vendetta duet from Rigoletto had been made in May of 1926, but the sides were never approved for release, and have proved elusive. The “Largo,” which we will meet again, is thus once more our only trace of him in what would seem to have been a highly compatible role. The above reservations notwithstanding, it’s a joy to hear this voice insouciantly warbling its alternations of the high G and A (as if preparing for a trill), and the overall brilliance and plentitude of tone on this recording. (Yes, those repeated Es on “per carità, per carità” are “too open,” but they’re clipped short, so—no harm, no foul.)

• • • • •

Four days after the recording session that produced the Ballo and Barbiere arias, Tibbett sang his first Germont in New York (19 April 1930), with Bori and Gigli the other principals and Vincenzo Bellezza conducting; it was to be one of his most eloquent roles over the next decade. But then it was back to Hollywood, where he remained through the end of the year for the filming of two more movies, New Moon and The Prodigal. In New Moon, derived from a Sigmund Romberg operetta that had had a substantial Broadway run a couple of years earlier, his co-star was Grace Moore, like Tibbett a small-town American (born Slabtown, Tennessee), and the only female singer of the era (or since, for that matter), who— though never quite of Tibbett’s artistic stature—achieved something close to his level of popular standing with a blend of operatic, movie (Oscar nomination for One Night of Love, etc.) and radio success. They were a glam couple onscreen, and a romantic item between takes. The singing was still being done live and in real time, and while the constrained, single-shot, single-angle framing of the captivating duet “Wanting You” is to our eyes limited and quaint, I am filled with admiration at the sight of these two singers pouring forth full-throated tone on an early-talkie set without a hint of undue respiratory effort or self-consciousness, Tibbett’s voice reveling in its easy, brilliant top, and Moore’s in its yeasty, warm chest blend at the bottom. They were, in the fashion of their time, decidedly cool. In The Prodigal (also called The Southerner), Tibbett plays a man torn between a settled life and the independence of the open road. His romantic interest, Esther Ralston, was a well-established actress but, alas, not a singer. So Tibbett is, vocally speaking, on his own save for some song-and-dance backup of the “Cheerful Darkie” variety.

These two movies were shot in quick succession and released just six weeks apart in January and February of 1931, and selected songs from them recorded by Victor in March of that year, with catalogue numbers assigned in reverse order of the films’ release dates, thus:

Vincent Youmans/Billy Rose/Edward Eliscu: THE PRODIGAL: Without a Song and Oscar Straus/Arthur Freed: THE PRODIGAL: Life is a Dream, with studio orchestra, Nathaniel Shilkret, conductor (both 6 March 1931) (CD 3/3–4). These two make an odd couple. “Without a Song” was one of Vincent Youmans’ biggest hits, proferred with regularity by any male singer with a touch of virility in the tone (and by some without) till well after World War II, though frequently with a change in the lyrics to “A man is born” from the original’s “A darkie’s born.” Tibbett’s, though, remains the iconic version, for reasons obvious to anyone hearing it. He sings it in a casually assumed Southern, blackish accent. “Life Is a Dream,” on the other hand, is another fully elaborated, rangey Oscar Straus waltz song with a blandishing melody, rendered with the singer’s most polished High Society American elocution and most cultivated neoViennese musical manner. Listen to the matched accomplishments of the ringing high Gs (two at full throttle, the third at a mezzo piano), the barely breathed–into-life onsets of “Only in dreams,” and the pianissimo high ending. We could say that these two sides give us Hollywood’s default escape options for Depression-era Americans—the merrily singing hobo of the open road and the EuroAmerican salon sophisticate wafting us to Dreamland. Tibbett evokes both without batting an eye.