In 1938 Foster won the MacDowell Competition and in 1940 the first Edgar M. Leventritt Prize. His Leventritt award led to his debut with the New York Philharmonic in 1941, playing Beethoven’s C Minor Concerto under John Barbirolli, for which Foster composed his own first movement cadenza for the performance. Fortunately, this performance was recorded off the air and we are pleased to be able to include it in our compilation. From 1952 until his death, Sidney Foster was a tenured professor at Indiana University. This seven-CD set contains carefully chosen performances recorded during this time, from 1952 to 1973.

CD 1 (81:08) | ||

15 January 1966, Salt Lake City, Utah | ||

TCHAIKOVSKY: | ||

| Concerto No. 1 in B-flat Minor, Op. 23 1 | ||

| 1. | I. Allegro non troppo e molto maestoso—Allegro con spirito | 20:24 |

| 2. | II. Andantino semplice—Prestissimo—Tempo I | 6:28 |

| 3. | III. Allegro con fuoco—Molto meno mosso—Allegro vivo | 6:39 |

| with the Utah Symphony, Maurice Abravanel, conductor | ||

| This was made from an archival recording of a live broadcast and is not edited. 1 Toward the end of the first movement of this recording, the right channel of the stereo signal drops out for approximately four minutes. We have repaired this flaw by using the left channel to replace the right channel during this four-minute lacuna. | ||

23 March 1941, New York City | ||

BEETHOVEN: | ||

| Concerto No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 37 | ||

| 4. | Opening announcement | 1:00 |

| 5. | I. Allegro con brio (cadenza by Sidney Foster) | 15:21 |

| 6. | II. Largo | 9:44 |

| 7. | III. Rondo—Allegro | 8:12 |

| with the New York Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra, Sir John Barbirolli, conductor | ||

| This was made from a recording of a live broadcast and is not edited. | ||

29 March 1955, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

BACH-LISZT: | ||

| 8. | Fantasia and Fugue in G Minor, BWV 542 | 11:03 |

10 October 1965, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

MENDELSSOHN: | ||

| 9. | Songs Without Words, Op. 62, No. 1, “May Breezes” | 2:17 |

CD 2 (77:33) | ||

3 May 1954, Complete Recital, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

MENDELSSOHN: | ||

| Fantasy in F-sharp Minor, Op. 28 | ||

| 1. | I. Con moto agitato | 4:44 |

| 2. | II. Allegro con moto | 3:09 |

| 3. | III. Presto | 4:23 |

SCHUMANN: | ||

| Carnaval, Op. 9 | ||

| 4. | I. Préambule | 2:11 |

| 5. | II. Pierrot | 0:54 |

| 6. | III. Arlequin | 0:37 |

| 7. | IV. Valse noble | 1:05 |

| 8. | V. Eusebius | 1:39 |

| 9. | VI. Florestan | 0:45 |

| 10. | VII. Coquette | 0:58 |

| 11. | VIII. Réplique | 0:27 |

| 12. | IX. Papillons | 0:34 |

| 13. | X. A.S.C.H—S.C.H.A. “Lettres dansantes” | 0:39 |

| 14. | XI. Chiarina | 0:54 |

| 15. | XII. Chopin | 1:33 |

| 16. | XIII. Estrella | 0:22 |

| 17. | XIV. Reconnaissance | 1:19 |

| 18. | XV. Pantalon et Colombine | 0:52 |

| 19. | XVI. Valse allemande | 0:35 |

| 20. | XVII. Paganini | 1:28 |

| 21. | XVIII. Aveu | 1:03 |

| 22. | XIX. Promenade | 1:52 |

| 23. | XX. Pause | 0:16 |

| 24. | XXI. Marche des “Davidsbündler” contre les Philistins | 3:26 |

CHOPIN: | ||

| Sonata No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 35 | ||

| 25. | I. Grave—Doppio movimento | 7:14 |

| 26. | II. Scherzo—Piu lento—Tempo I | 5:38 |

| 27. | III. Marche funèbre: Lento | 6:25 |

| 28. | IV. Finale: Presto | 1:39 |

LISZT: | ||

| 29. | Consolation in D-flat, S. 172, No. 3 | 3:57 |

| 30. | Venezia e Napoli, S. 162, No. 3, “Tarantella” | 7:19 |

SCRIABIN: | ||

| 31. | Prelude for the left hand, Op. 9, No. 1 | 2:45 |

WEBER: | ||

| 32. | Sonata No. 1 in C, Op. 24: Fourth Movement, “Perpetuum Mobile” | 3:40 |

SCHUMANN: | ||

| 33. | Romance in F-sharp, Op. 28, No. 2 | 3:12 |

CD 3 (78:47) | ||

26 November 1973, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

MOZART: | ||

| Sonata No. 5 in G, K. 283 | ||

| 1. | I. Allegro | 4:30 |

| 2. | II. Andante | 3:38 |

| 3. | III. Presto | 3:17 |

13 November 1971, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

BEETHOVEN: | ||

| Sonata No. 21 in C, Op. 53, “Waldstein” | ||

| 4. | I. Allegro con brio | 8:05 |

| 5. | II. Introduzione: Adagio molto | 3:16 |

| 6. | III. Rondo: Allegretto moderato—Prestissimo | 9:53 |

30 October 1966, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

BEETHOVEN: | ||

| Sonata No. 31 in A-flat, Op. 110 | ||

| 7. | I. Moderato cantabile molto espressivo | 6:19 |

| 8. | II. Allegro molto | 1:57 |

| 9. | III. Adagio ma non troppo—Allegro ma non troppo | 9:17 |

8 February 1968, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

LISZT: | ||

| Sonata in B Minor, S. 178 | ||

| 10. | Lento assai—Allegro energico | 11:09 |

| 11. | Andante sostenuto | 7:09 |

| 12. | Allegro energico | 10:20 |

CD 4 (79:33) | ||

30 June 1968, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

| 1. | SCHUMANN: Papillons, Op. 2 | 14:27 |

3 May 1962, Tokyo | ||

SCHUMANN: | ||

| Concerto in A Minor, Op. 54 | ||

| 2. | I. Allegro affetuoso | 14:38 |

| 3. | II. Intermezzo | 5:05 |

| 4. | III. Allegro vivace | 9:53 |

| with the Japan Philharmonic, Michiaki Okuda, conductor | ||

19 February 1970, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

BRAHMS: | ||

| Sonata No. 3 in F Minor, Op. 5 | ||

| 5. | I. Allegro maestoso | 7:18 |

| 6. | II. Andante: Andante espressivo | 10:04 |

| 7. | III. Scherzo: Allegro energico | 4:01 |

| 8. | IV. Intermezzo: Andante molto | 3:04 |

| 9. | V. Finale: Allegro moderato ma rubato | 7:11 |

26 November 1973, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

GRIEG: | ||

| 10. | Nocturne in C, Op. 54, No. 4 | 3:52 |

CD 5 (79:08) | ||

27 April 1952, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

FRANCK: | ||

| Prelude, Chorale, and Fugue | ||

| 1. | I. Prelude | 4:13 |

| 2. | II. Chorale | 5:30 |

| 3. | III. Fugue | 6:30 |

27 April 1952, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

CHOPIN: | ||

| 4. | Fantasy in F Minor, Op. 49 | 11:36 |

27 April 1952, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

CHOPIN: | ||

| 5. | Etude in C-sharp Minor, Op. 10, No. 4 | 2:01 |

| 6. | Etude in G-flat, Op. 10, No. 5, “Black Keys” | 1:30 |

| 7. | Etude in E-flat Minor, Op. 10, No. 6 | 3:25 |

| 8. | Etude in F, Op. 10, No. 8 | 2:25 |

19 February 1970, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

CHOPIN: | ||

| Sonata No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 58 | ||

| 9. | I. Allegro maestoso | 9:22 |

| 10. | II. Scherzo: Molto vivace | 2:22 |

| 11. | III. Largo | 7:46 |

| 12. | IV. Finale: Presto non tanto | 5:15 |

1 July 1969, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

CHOPIN: | ||

| 13. | Ballade No. 4 in F Minor, Op. 52 | 11:46 |

19 January 1975, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

CHOPIN-FOSTER: | ||

| 14. | Waltz in D-flat, Op. 64, No. 1, “Minute Waltz” | 2:00 |

30 June 1968, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

MOSZKOWSKI: | ||

| 15. | Guitarre, Op. 45, No. 2 | 3:27 |

CD 6 (81:12) | ||

3 November 1974, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | ||

RACHMANINOFF: | ||

| Sonata No. 2 in B-flat Minor, Op. 36 | ||

| 1. | I. Allegro agitato | 8:37 |

| 2. | II. Non allegro | 5:59 |

| 3. | III. Allegro molto | 6:26 |

2 February 1974, Glassboro, New Jersey | ||

SCRIABIN: | ||

| 4. | Etude in D-flat, Op. 42, No. 1 | 2:02 |

| 5. | Etude in F-sharp Minor, Op. 42, No. 2 | 1:06 |

| 6. | Etude in F-sharp, Op. 42, No. 4 | 1:35 |

| 7. | Etude in C-sharp Minor, Op. 42, No. 5 | 3:38 |

8 February 1968, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

SCRIABIN: | ||

| 8. | Sonata No. 9, Op. 68, “Black Mass” | 8:17 |

8 July 1964, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

BARTÓK: | ||

| 9. | Dirge, Op. 9a, No. 4 | 4:12 |

2 October 1961, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

PROKOFIEV: | ||

| Sonata No. 9 in C, Op. 103 | ||

| 10. | I. Allegretto | 6:47 |

| 11. | II. Allegro strepitoso | 2:46 |

| 12. | III. Andante tranquillo | 6:39 |

| 13. | IV. Allegro con brio, ma non troppo presto | 5:54 |

2 October 1961, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

PROKOFIEV: | ||

| Visions Fugitives, Op. 22: | ||

| 14. | No. 1 | 1:03 |

| 15. | No. 3 | 1:00 |

| 16. | No. 10 | 0:49 |

| 17. | No. 11 | 1:08 |

| 18. | No. 14 | 1:07 |

| 19. | No. 15 | 0:43 |

| 20. | No. 8 | 1:14 |

| 21. | No. 18 | 1:23 |

2 October 1961, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

PROKOFIEV: | ||

| 22. | Gavotte, Op. 32, No. 3 | 1:47 |

8 February 1968, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

PADEREWSKI: | ||

| 23. | Cracovienne Fantastique, Op. 14, No. 6 | 3:18 |

27 April 1952, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

HUMMEL: | ||

| 24. | Rondo in E-flat, Op. 11 | 3:44 |

CD 7 (81:08) | ||

19 May 1957, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

BACH-LISZT: | ||

| 1. | Prelude and Fugue in A Minor, BWV. 543 | 9:37 |

27 April 1952, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

MOZART: | ||

| 2. | Variations on a Minuet of Duport, K. 573 | 7:20 |

29 March 1955, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

BRAHMS: | ||

| Four Ballades, Op. 10 | ||

| 3. | No. 1 in D Minor | 4:20 |

| 4. | No. 2 in D Major | 5:30 |

| 5. | No. 3 in B Minor | 2:36 |

| 6. | No. 4 in B Major | 7:18 |

27 April 1952, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

DEBUSSY: | ||

| 7. | La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune, Preludes Book II, No. 7 | 3:52 |

| 8. | Le vent dans la plaine, Preludes Book I, No. 3 | 2:26 |

27 April 1952, Bloomington, Indiana | ||

DELLO JOIO: | ||

| Sonata No. 3 in G | ||

| 9. | I. Theme and Five Variations | 5:20 |

| 10. | II. Presto e leggiero | 1:17 |

| 11. | III. Adagio | 4:06 |

| 12. | IV. Allegro vivo e ritmico | 2:38 |

9-10 April 1965 Boston, Massachusetts | ||

BARTÓK: | ||

| Concerto No. 3 | ||

| 13. | I. Allegretto | 7:23 |

| 14. | II. Adagio religioso | 10:42 |

| 15. | III. Allegro vivace | 6:39 |

| with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Aaron Copland, conductor | ||

| This is from an archival recording made by the Boston Symphony Orchestra of two live broadcasts, 9 and 10 April 1965. The editing was done by the BSO and is not additionally edited. | ||

Producers: Scott Kessler and Ward Marston

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston, J. Richard Harris, and Raymond Edwards

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Booklet Notes: Alberto Reyes

Marston extends special thanks to Alberto Reyes for his tireless contribution to the production of this set, from assistance in selection of content to his provision of liner notes.

Marston would like to thank the orchestral committees as well as Ray F. Wellbaum, Orchestra Manager of the Boston Symphony; Miki Takebe, Director of Operations of the New York Philharmonic; and Cassandra Dozet, Director of Operations, and Steven Finkelstein, Development Coordinator, of the Utah Symphony, for their assistance and decision to allow the licensing of their performances.

Marston would like to thank the following people who lent assistance or provided tapes to be auditioned for inclusion in this set: the family of the late Caine Alder, who shared their extensive library of Sidney Foster performances: Mrs. Caine Alder, daughter Char Coleman, and son Chris Alder, Hans Boepple, Bridget P. Carr, Harry Coleman, Imelda Delgado Cortez, Morley Grossman, Donald Manildi, Kevin Mostyn, and Veda Zuponcic.

Marston would like to thank the Curtis Institute, Indiana University, and Rowan University, formerly known as Glassboro State College, for providing the source material for Mr. Foster’s recitals.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

A NOTE ABOUT THE RECORDINGS AND THE ARTIST

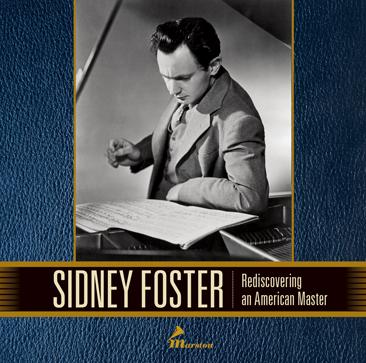

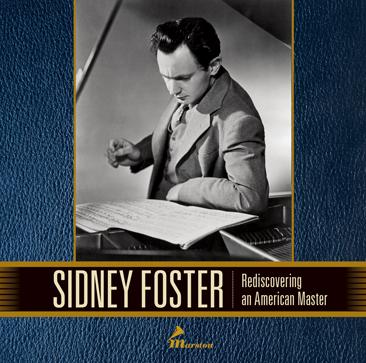

This CD set is a rare musical treasure. It contains live performances by a master pianist who, by those inexplicable twists and turns of life, never reached the heights of celebrity to which his artistry entitled him.

Live performances, by definition, are ephemeral events that fade from our consciousness with the last echoes of the music, only to live precariously in our imperfect memory. The fact that these particular live performances were spared that fate was something of a fluke. Some took place about half a century ago on the stages of Indiana University, where a single, permanent hanging microphone was switched on during faculty recitals. That was all. There was no thought of producing a recording as a musical event; it was a mere document of a recital that had taken place.

One recording comes from a broadcast of a 1941 Carnegie Hall performance with the New York Philharmonic, which some anonymous soul, sitting by a radio somewhere, captured off the air and rescued from oblivion. Others took place in different venues far from the major concert circuits.

But great art and the labors of a great artist, even if casually recorded decades ago, have a way of surviving. These tapes were cherished by the lucky few that had access to them, while awaiting discovery by a larger audience. Now, thanks to Marston, they finally reach the public.

Sidney Foster was born in Florence, South Carolina on 23 May 1917. Early on, he showed all the signs of talent and precocity that great musicians share, playing by ear anything he heard on a gramophone or on the radio, and improvising. In 1925, the family moved to Miami, Florida, and Foster took piano lessons from Earl Chester Smith. Josef Hofmann, the legendary pianist, then Director of the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, heard young Sidney play and recommended he be admitted to Curtis. At the age of ten, Foster was one of the youngest pianists ever accepted at the famous school, and he started lessons with Russian pianist Isabelle Vengerova. After two years, he went back to his family, which had moved to New Orleans, and studied with Walter Goldstein. Then, in 1934, he returned to Curtis to study with American pianist David Saperton, Leopold Godowsky’s son-in-law.

In 1938, he won the MacDowell Competition and in 1940 the first Edgar M. Leventritt prize, both in New York. The Leventritt award led to his debut with the New York Philharmonic in 1941, playing Beethoven’s C Minor Concerto under John Barbirolli, and composing his own first movement cadenza for the performance. The debut was a big success, and Noel Strauss of the New York Times wrote “with all the enthusiasm and fire of youth, Mr. Foster, whose approach to the keyboard was of a noble, heroic type, gave the concerto a reading in the grand manner...he proved himself a richly gifted performer, and his brilliant playing occasioned a prolonged ovation.”

He embarked on a career that included regular recitals at Carnegie Hall, performances with the New York Philharmonic at Lewisohn Stadium, the Chicago Symphony at Ravinia, the Boston Symphony, the Houston Symphony, the Cincinnati Symphony, the Minneapolis Symphony, the Dallas Symphony, the Indianapolis Symphony, the Utah Symphony, the Portland Symphony, and dozens of other orchestras.

In the early 1960s, he played in England, Holland, Germany, Israel, Japan, and toured the Soviet Union in a whirlwind visit that included twenty-two concerts in thirty days, performing four concertos and three different recital programs in Moscow, Leningrad, Minsk, Tbilisi, Yerevan, Rostov-on-Don and Kishinev.

Despite eliciting universal acclaim from critics and audiences alike, Foster was practically ignored by the recording industry. His only commercial recordings were a couple of Mozart concertos with the Vienna Chamber Orchestra and a set of Clementi sonatinas, both for the Musical Heritage Society. In 1993, the International Piano Archives at Maryland published posthumously Ovation to Sidney Foster, a two-CD set that included some live performances at Indiana University.

He devoted a great part of his time to teaching. In 1949, he taught at Florida State University, and from 1952 until his death on 7 February 1977, he was a tenured professor at Indiana University, where he received the Frederic Bachman Lieber Award and was named Distinguished Professor.

He was married to Bronja Singer, also a student of David Saperton at Curtis, and had two sons, Lincoln and Justin.

SIDNEY FOSTER. A REMEMBRANCE

When I first heard Sidney Foster in 1966, in my home country of Uruguay, at a recital that included performances of the Appassionata and Rachmaninoff’s Second Sonata, I was beguiled by his beautiful sound, mesmerized by the articulate virtuosity of his fingers, and stunned by the volcanic intensity he was capable of unleashing in those monumental works. But as an aspiring, eighteen-year-old pianist, I was not ready yet to understand the depths of his artistry. It was only later that same year, when I arrived in Bloomington and began regular lessons with him at Indiana University, that I started to glimpse how much profound thought and artistic insight there was behind every one of Foster’s performances.

Sidney Foster lived in a lush, leafy neighborhood of Bloomington, not far from some of the other great musicians who graced that musical Parnassum, luminaries such as Josef Gingold, János Starker, Abbey Simon, György Sebo˝k, Menahem Pressler, Margaret Harshaw, and, later on, Jorge Bolet. As my parents did not have the means to support my studies in the U.S., Sidney had invited me to live with his family. The house was a reflection of the Fosters’ intellectual curiosity and eclecticism. Every room was brimming with books. The bookshelves displayed the broad range of their interests. Although books about music were abundant, they were overshadowed by numerous works on psychoanalysis, science, history, language, and literature. There was a well-thumbed Encyclopedia Britannica in the dining area, and if factual doubts arose on any subject, the appropriate volume would be brought to the table to dispel them. In fact, the dinner table was the daily center of family life, as we assembled punctually at 6:00 p.m., to eat and to watch the CBS News broadcast with Walter Cronkite. With the Vietnam War raging at that time, politics was always a topic of discussion. The Fosters were ardent supporters of the Democratic Party, and Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt were their heroes. But although they professed sincere admiration for Lyndon Johnson and his political prowess in legislating the socially progressive Great Society programs, Johnson’s hard-headed pursuit of the war in Indochina was starting to appall them. Sidney and his wife Bronja took turns with the cooking. Perhaps in deference to my Latin sensibilities they prepared a very tasty chili con carne for my first dinner at the house, and I didn’t have the heart to tell them that I had never come near that Mexican-American staple in my life. But soon Sidney taught me to make coffee in an old Melitta filter cone, and I felt I was doing my very modest bit for the eminently satisfying (both, culinary and intellectual) daily ritual of dinner with the Fosters.

Foster’s childhood friends, pianists Abbey Simon and Jorge Bolet had come to teach in Indiana, arriving from Geneva and Spain, respectively, at Sidney’s initiative, and were weekly, sometimes nightly, dinner guests. The conversation centered on political or artistic subjects, and often, to my delight, on pianistic matters. It was a privilege to listen to three towering pianists relating their memories of great pianists I never got to hear, such as Hofmann, Rachmaninoff, Moiseiwitsch, Mischa Levitzki, Ossip Gabrilowitsch, the young Horowitz, and their contemporary William Kapell. They expounded on diverse topics such as musical interpretation —both their own and their colleagues’—the vagaries of modern recital programming, the tastes of Soviet audiences (“La Campanella country,” as Simon called them), and the challenges of teaching. Sometimes they would reminisce about their salad days at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia. In that great school, the three of them, as well as Bronja, had studied with David Saperton. There were tales about the imperiousness of Isabelle Vengerova, the meanness of composition teacher Rosario Scalero, and the strict theory lessons of Madame Longy-Miquelle. Humor was never absent in those conversations, as they recalled, with glee but without malice, some anecdote about their fellow Curtis student Shura Cherkassky, or a prank they once played on their good friend Russian pianist Alexander Uninsky that involved a fictitious donation of violin strings to France—where Uninsky was going on tour after the war—by the non-existent organization “Guts for France.”

Other times, violinists Josef Gingold and Isaac Stern, violist David Dawson, or cellists Bernie Greenhouse and Leonard Rose were guests, and the conversation turned to their memories of the legendary Stokowski sound in Philadelphia, Toscanini’s wit at the NBC Orchestra, the impenetrability of Reiner’s baton technique in Chicago, and their admiration for George Szell in Cleveland and Pablo Casals in Puerto Rico. A very heady environment for a young South American student just beginning to learn how to think about music and musicians, indeed!

• • • • •

In my very first lessons Foster revealed not only his original way of thinking about music-making but also his unusual capacity to articulate, verbally, his ideas. He always said that his first ambition had been to compose. Perhaps this is what gave him the ability to approach any piece of music from the standpoint of the compositional process that allowed the author to go from the germ of an initial idea to the finished work.

He was a kind of “structuralist.” Not in the intellectual “French” meaning of the word (he abhorred all the pedantic, “philosophical” verbiage that, in the minds of young, impressionable students, passes for teaching,) but in the concrete sense that the dictionary attributes to the word structure: “the manner in which a … whole is constructed.” He would teach us to recognize the basic, constitutive elements which through development and combination would result in a coherent, self-contained organism. This approach meant that Foster’s performances of a work had a natural, narrative quality. He was capable of “speaking” the music with clarity and eloquence. Even a piece one had not heard before, e.g., Prokofiev’s Ninth Sonata, Hofmann’s Berceuse, or Saperton’s Zephyr, became instantly clear in his hands.

To Foster, musical meaning was to be found in the set of relationships among all the musical elements: harmonic, dynamic, tempo, and temporal (the idea that when an event occurs, whether as a first utterance or as a repetition, is crucial to determine its expressive value.) He organized his playing around the structure of the musical bar and it’s implicit differences of intensity between the beats. That basic sense of pulse, his infallible rhythm and the permanent play of tension and release in the harmonic structure of a musical phrase were three pillars that made his piano playing intensely, compellingly alive.

None of this should remotely suggest that expression, affect, and drama were not his concern as pianist and teacher. To the contrary: he was a master at conveying, in his playing and in his teaching, the subtle differences in dynamics and timing that make for natural expression in music. As a performer, he was keenly aware that character and mood are in constant change, following the harmonic and rhythmic unfolding of a passage. There was never a sense of a premeditated imposition of a rigid, overall mood dominating a whole section; what emerged was a subtly varied sequence of statements, reflecting music’s miraculous capacity to mirror the unfolding of our own conscious and unconscious emotions and thought processes.

Tone was also a hallmark of his aesthetics of piano playing. In the matter of tone production, his advocacy of arm weight resulted in an unforced, fully resonant sound that, in the manner of the great masters of the past, projected through the entire acoustic space. He understood the problems that the modern piano poses for the performer, with its homogeneity of color across the full extent of the keyboard. This homogeneity can result in a thick, muddy, impenetrable tone if the pianist is not able to control the dynamics of simultaneous sounds. The solution for Foster was to strive for maximum differentiation between melody, basses, and inner textures, and the result was a tridimensional sound, in which melodies soared above a carefully delineated bass line, while the inner textures emerged clearly in all their harmonic richness and variety. He pedaled with mastery and imagination, taking full advantage of the middle, “sostenuto” pedal. Sometimes he would depress soundlessly a key in the bass or middle range, so as to catch it with the “sostenuto”pedal and make it sound later, while cleaning any dissonances with the right pedal. Other times, he would land on a bass note that he wanted to prolong for the sake of a rich sonority or contrapuntal effect, and instantly release the notes above, so that only that note, caught on the “sostenuto” pedal, would underpin the resulting texture. Another arrow in Foster’s quiver of tonal resources was the subtle desynchronizing of voices. When contrapuntal voices were too close in range, he never hesitated to separate them in time, without altering the natural flow of the lines, thus allowing each of them to be heard clearly. His magisterial account of Chopin’s F Minor Ballade is an object lesson in the use of desynchronization for the purposes of tonal beauty and contrapuntal clarity.

Sidney Foster appeared in New York’s rich music scene around the middle of the 20th Century. Logically, he was very aware of the contemporary developments in musicology and the burgeoning interest in “authenticity” in performance. Urtext editions proliferated and were instrumental in ridding interpretation of certain “accretions” that tradition had imposed on performance. But Foster’s intelligence and musical acumen allowed him to avoid the trap of thinking that piano playing could simply be reduced to an accurate rendering of the text. For Foster, the art of piano playing was the art of conveying musical meaning, and meaning was intrinsic to the work, not just a function of the composer’s intentions. He was not indifferent to scholarly research. Tellingly, the first book he gave me as a present was Walter Emery’s volume on Bach’s ornamentation. And he thoroughly distinguished between originality or creativity, and ignorant or uninformed playing. But he understood the limits and imprecision of musical notation and did not elevate the printed score to the position of a definitive and unique blueprint of the meaning of the work. Perhaps, he saw the score as only a vague shadow of the composer’s concept. Maybe he was an avatar of the intellectual zeitgeist of the mid-century, which found its maximum expression in Roland Barthes’s essay “The Death of the Author,” and elevated readers to a position of coequal creators of meaning. But it was clear in Foster’s playing and teaching that there was no quasi-religious reverence for the “wishes” or the “true intentions” of the composer. As an extensive reader of Freud, Foster knew too much about the pervasive influence of the unconscious in every creative act to slavishly follow the instructions of a score without a thorough critical analysis based on musical and aesthetic considerations.

Foster’s way of filling the gaps left by notation was to highlight musical prosody, that is, those variations of stress and emphasis that contribute to meaning. He used the differences and contrasts of dynamics and timing to convey such meaning. Foster’s score markings for his students offer a fascinating view of his mastery of musical prosody. He lavishly used dynamic “hairpins” to suggest the constant rise and ebb of intensity and gradations of volume in a phrase or group of phrases. Foster’s own phrase marks and slurs reveal his own opinion about the parsing and shaping of melodies. He had absolutely no qualms in disobeying the printed dynamic marking if the musical meaning of a passage demanded it. The sense of inevitability in his approach to dynamics always managed to convince the listener.

The manipulation of time and his use of rubato for rhetorical and expressive purposes gave Foster’s performances an intense declamatory character that commanded the listener’s attention. As critic Ross Parmenter of the New York Times noted in a 1948 review, “one of Mr. Foster’s gifts is to make his interpretations relate a story, so the listener feels that something definite and complete has been told by the end of a piece.” He employed the rhetorical devices of an earlier era, such as arpeggiation of chords and the advancing of certain notes in the bass line, with great taste and to persuasive expressive effect, although he never explicitly advocated doing so in his teaching. He favored brisk tempi in fast movements and a forward-moving pace in slow ones. His velocity and articulation were legendary. There are live recordings of a few Chopin etudes that have become something of a cult object unmatched as they are in speed, momentum, drama, and control (Noel Strauss described in the New York Times his performance of Op.10, Nº4 at Carnegie Hall in 1941 as “a bravura reading at immense speed that was fairly breathtaking”). Indeed, he never played it safe. He was unconcerned by wrong notes and went straight to the core of the musical message. His performances never sought to reproduce a fixed interpretation arrived at beforehand. He aimed to recreate the work on the spot and encouraged his students to do the same. By the same token, he never put too much store in recordings, believing that music making was a process that unfolded in time, in a particular place, in specific acoustical circumstances, to be listened to strictly as it was created. He did not pursue recording opportunities, and he never, ever, listened to tapes of his past performances. We are extremely lucky that he was so generous about performing at Indiana University, as the tapes of those recitals, plus a few live recordings from New York, Boston, Tokyo and a handful of U.S. cities are all we have to appreciate his commanding artistry.

Foster’s repertory ranged from Bach to Prokofiev, although he also broke a lance on behalf of his contemporaries when he premiered Norman Dello Joio’s first and second Sonatas in consecutive Carnegie Hall recitals in the forties. The Classical composers he performed in public included a sprinkle of Mozart and a hefty chunk of Beethoven sonatas, from the early Pathetique to Op. 110. His performances of the two major middle sonatas, the Waldstein and Appassionata, were archetypal versions of relentless drive, drama, and muscularity. Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, and Brahms made up the bulk of his Romantic repertory. Perhaps Chopin’s infinite imagination inspired Foster to display the widest range of expressive and contrapuntal details, with a fully orchestral sound, lyrical melodic lines, and insistent inner voices within an overall framework that never bowed to the then common view of Chopin as a composer of small-scale, “poetic” works. The French Impressionists were not entirely absent from his programs. Some Debussy preludes —La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune, Le vent dans la plaine, Feux d’artifice, and a couple of other works—show up on a few of his youthful programs. So does the Ravel Toccata. In fact, he liked to group shorter works that may be categorized as vaguely impressionistic, or nationalistic character pieces, in the second half of his recitals, and thus performed Albéniz, Turina, Délibes-Dohnányi, Bartók, Scriabin, Shostakovich, Prokofiev (he loved the Visions Fugitives and the Toccata) and the encore-type virtuoso repertory by Moskowsky, Godowsky, Paderewski, and Hofmann.

Foster performed quite a bit of chamber music, from his early professional days, when he toured with the LeRoy Foster Scholz Trio (flute, piano, and cello) until the end of his life. For the trio, Foster composed, under the pseudonym E. Silvera, a suite named Allende el Río which was praised in the press by composer and critic Virgil Thomson, no less. In Indiana University he played the complete Beethoven sonatas for violin and piano with violinist and legendary teacher Josef Gingold, and appeared with the Berkshire String Quartet and other faculty members and ensembles. I used to offer to turn pages for his chamber music performances (I particularly remember a gorgeous Trout quintet, a Dvórak piano quartet and Fauré’s A Major Sonata for violin and piano) and he graciously allowed me to do so. I was fascinated by the economy and efficiency of his hand motions, and more than once forgot to turn the page. None of this posed any problems for Foster as it usually took just one rehearsal for him to memorize the piano part, and there were never any “accidents” provoked by my distractions.

His piano and orchestra repertory ranged from Mozart to Bartók. For his debut with the New York Philharmonic in 1941, as the first winner of the coveted Leventritt Prize, he played Beethoven´s C Minor Concerto and composed his own cadenza. An off the air recording of the broadcast has preserved for us this tour de force of bravura writing and playing, as the cadenza shows impeccable stylistic awareness and daring imagination, in a framework of strictly Beethovenian passagework. Unfortunately there are no known recordings of a memorable Chopin E Minor Concerto I heard him play in Indianapolis, a concerto he also played at Ravinia with the Chicago Symphony and in Cincinnati, a Brahms B-flat Concerto he played with the Minneapolis Symphony and Dimitri Mitropoulos, a Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini he did with Antal Doráti, a Liszt E-flat Concerto he played with his brother-in-law, Jacques Singer, in Portland, and several other concerti. But there are recordings of a towering Tchaikovsky B-flat Minor Concerto from Utah with Maurice Abravanel, an idiomatic Bartók Third Concerto with Aaron Copland conducting the Boston Symphony, and a wonderful Schumann A Minor Concerto from Japan.

• • • • •

Foster’s generosity with his resources and with his time had no bounds. His teaching schedule at Indiana University far exceeded the requirements of the school. Although his regular lessons, lasting one hour, were very well organized, if a student’s impending performance or participation in a competition so required, he went back to school after dinner and spent two or three extra hours listening and advising. As I prepared the repertory for the Tchaikovsky competition in Moscow in 1970, he would gladly sit at the second piano and sightread, flawlessly, the orchestra part of Prokofiev’s Second Concerto, while listening to the solo part and offering not only interpretive solutions but also suggestions for fingering or rearranging the distribution of notes between the hands. He was a firm believer in the redistribution of notes for the purpose of clarifying textures and facilitating performance. He was, indeed, imaginatively creative in that respect, and to this day his students eagerly seek the marked scores of their colleagues when they have to learn a new piece or when they have to teach those works to their own pupils. Another facet of his generosity as teacher was the holding of a collective piano class, from 2 to 4, every Sunday afternoon during the school year. His class assembled in IU’s Recital Hall and listened to the students’ performances of works ready to be presented in recital. Foster encouraged and moderated the critical discussion of those performances, teaching us to think clearly and to articulate our ideas, and enriching our artistic judgment and our capacity to convey knowledge to others.

He always put the learning interests of his students above his own ego considerations. When I learned the Prokofiev Second for the Moscow competition, Foster asked his esteemed colleague Jorge Bolet to listen to me. Bolet had been the first pianist to record the then rather obscure piece and was an unquestionable authority on it. Foster did not play the work, so he naturally felt that I could have a richer learning experience with the pianist that had already made it his own. But his own lack of egoism vis-a-vis his students getting advice from other accomplished artists also extended to my working on other pieces. As Foster (and the whole world) understood Bolet to be an exceptionally insightful Liszt interpreter, he also suggested I play for Bolet the Liszt Sonata, the Funérailles, and a few of the Transcendental Études. This from a pianist that was capable of tossing off towering performances of the Liszt Sonata, and Venezia e Napoli, as Foster’s live recordings attest!

• • • • •

Sidney Foster’s strength and stamina were put to the test by a series of severe health problems. He had a heart attack at the age of thirty-eight, which interrupted his performing career for almost four years. At fifty, he broke a leg in a car accident. In between, he was diagnosed with a complex disease of the bone marrow, myeloid metaplasia, which left him at times anemic and gravely affected his energy levels, although as all of his students could attest, there was never any slacking of his teaching activities. When the disease was detected he was given a prognosis of about seven more years to live. The fact that he survived fourteen years is a testimony of the extraordinary care he received from his wife and family, in terms of nutrition and love, and of his will to live and positive outlook on life. I marvel at my own extreme good fortune, as when I met him in Montevideo in 1966, he was already under a kind of medical death sentence. I never knew it until two or three years before his passing, in February 1977, when the enlargement of his spleen became too evident to hide. Even so, he continued performing and learning repertory. In 1976, he learned American composer Ernest Schelling’s Suite Fantastique for piano and orchestra, which had not been performed since the thirties. I had already moved to New York City and was thrilled to receive a call from him, asking me to accompany him on second piano on a private performance of the Schelling for conductor André Kostelanetz and New York Times music critic Harold Schonberg, on the premises of the Baldwin Piano Company on 58th Street. That was the last time I heard Sidney play. A few months later, on the weekend of 5-6 February 1977, I was by his bedside in Boston’s New England Medical Center, and although his health was severely compromised by then, we didn’t expect that, having come through another operation, he would die in the early hours of 7 February.

Sidney Foster, the pianist and teacher, was a glorious paradox. He, the pianist who could play faultlessly by ear anything he heard, who could read at first sight the most complex piece of music, who was capable of sitting down in his studio to demonstrate any passage of his vast repertory at the drop of a hat, was also (unlike other musical geniuses) the most intellectually insightful and verbally articulate teacher any aspiring young pianist could ever encounter in his studies. On the night before I moved from Bloomington to New York, in August 1974, after saying our goodbyes to Sidney and Bronja, and as we were walking to our car in the balmy and fragrant Bloomington night, my wife and I heard Sidney through the window, tinkling at the piano. We stopped and at first could not recognize the piece, which he seemed to have picked up in mid-movement. It took us a while to realize that he was faithfully reproducing a passage from a Prokofiev symphony he probably had heard recently on the radio. It was the most awesome musical parting gift we could hope for.

©Alberto Reyes, 2018

Alberto Reyes would like to thank Imelda Delgado for the wealth of biographical information contained in her extensively researched book, An Intimate Portrait of Sidney Foster—Pianist and Mentor (Hamilton Books, Rodman & Littlefield Publishers, 2013) from which he drew for part of his essay contained herein.

Sidney Foster: Rediscovering a Master [pdf]

Jed Distler welcomes a survey exploring the legacy of an overlooked American pianist.

—Gramophone, March 2019

What’s in a name? – recordings by a great but unknown pianist rescued from the vaults [pdf]

This cultured prize-winning virtuoso... pupil of David Saperton (Godowsky’s son-in-law and teacher of Shura Cherkassky and the like) is a pianist whose range of imagination and ability to cue audible thunder will make you think again about everything he plays.

—Rob Cowan, Rob's Retro Classical

Fanfare review [pdf]

All but forgotten, Foster is a major discovery. Thanks to Marston’s transfer skills and musical instincts, the art of an important American pianist has been kept alive. The superb booklet contains a penetrating essay by Alberto Reyes, a student and colleague of Foster’s. It goes without saying that the sound quality is superb considering the variety of sources and range of dates.

—Henry Fogel, Fanfare

Music Web International review: Recommended [pdf]

I am astounded, listening to these live airings rescued from oblivion by the enterprising efforts of Marston Records, that the American pianist Sidney Foster never achieved the fame his artistry deserved.

This outstanding production deserves a prominent place on the shelves of anyone with an interest in the history of pianists and piano performance. Foster is an artist well-worth getting to know.

—Stephen Greenbank, Music Web International

Agora Classica review [pdf]

... there are performances in which Foster’s phenomenal facility is complemented by a rare poetic artistry. I have seldom heard a more mesmeric performance of Chopin’s Fourth Ballade, its volatile and elegiac character set free from conventions.

Other major successes include Scriabin’s and Prokofiev’s Ninth Sonatas, the dark Dostoyevsky recesses of the former matched by the unsettling whimsy of the latter.

No discussion of Sidney Foster would be complete without mention of his performance of four Chopin Études (Op 10, Nos 4,5,6 and 8). These are truly astonishing in their virtuosity and no more fiercely ignited (or wittily voiced) No 4 exists on record.

This is an issue that leaves you frequently bewitched, sometimes bothered and occasionally bewildered. Beautifully presented with many photographs and an essay by Foster’s devoted student, the Uruguayan pianist, Alberto Reyes.

—Bryce Morrison, Agora Classica

Sidney Foster Review In Artamag

The most gifted of Josef Hofmann's pupils? Certainly, but also the least known. Sidney Foster's reputation did not cross the Atlantic. He was ignored by recordings, save for one LP of Mozart concertos and another one of Clementi sonatas (sic). Transatlantic pianophiles hoarded the broadcast recordings of his appearances, where his art, brilliant and austere at the same time (his technique was as dazzling as his interpretations were thought-out) covered a large repertoire from Bach to Norman Dello Joio. The latter's Third Sonata, which Foster championed with panache, is a reminder of the mutual admiration between these two artists.

Everything is there, already, in his Carnegie Hall appearance of 23 March 1941, when John Barbirolli accompanied Foster in Beethoven's Third Concerto: the intelligent phrasing, the perfection of style, the large but controlled sonority, the classic gestures that show a lion of the piano husbanding his strength.

He is thoroughly athletic in an exhilarating Brahms' Third Sonata that shuns no risks, in a Liszt Sonata simultaneously refined and fiery, and in a Waldstein that is a collector's item. His perfect technique is effortless: just listen to his justly legendary four Chopin Etudes or his Rachmaninov's Second Sonata.

But above all, it is his palette of colors that astonishes us in his Brahms Ballades, two Debussy preludes and a nimble and precise Schumann Carnaval.

This musical portrait presented by Ward Marston is eloquent, even when the pianist has to tidy up the mess, as Foster navigates around the haphazard conducting of Aaron Copland in Bartok's Third Concerto. The publication is polished, as usual, with abundant images and enlightening notes by Alberto Reyes, who was Foster's pupil. Enjoying the seven discs chock-full of music in this admirable set makes us dream of a second installment.

—Jean-Charles Hoffelé, Artamag, 12 May 2019

Rediscovering Sidney Foster [pdf]

A master whose fame, by inexplicable meanders of life, has never been at the height of his talent and his musicality... Here is an invitation to a fascinating journey to discover rare musical treasures in the best quality reports possible, a publication recommended for fans of the piano.

—Maciej Chiżyński, Res Musica, June 2019