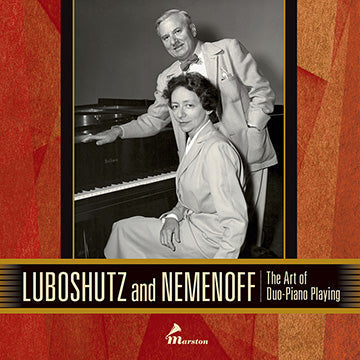

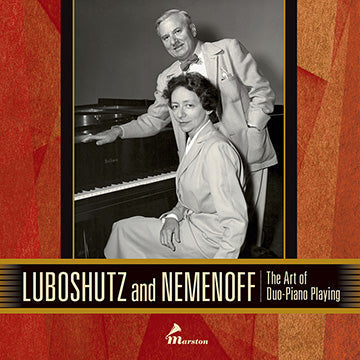

Pierre Luboshutz (1890–1971) and Genia Nemenoff (1905–1989) were husband and wife. Both were from musical families of Russian and Jewish heritage and both ultimately settled in New York by way of Germany and France. Pierre had established a fine reputation in Russia as a member of the Luboshutz Trio, comprised of Pierre and his two more famous sisters. He also became known as a successful accompanist who toured extensively with a variety of distinguished soloists. Genia, however, languished in the States: it was the Depression, her family was abroad, and musical opportunities were limited. Performing together was a wonderful solution, if not without risk: duo-piano teams were not featured on the concert circuit. Yet Pierre and Genia were not only undaunted, they were well-connected: Pierre had many important musician-colleagues and friends and Pierre’s sister Lea introduced the duo to her manager, the indomitable Sol Hurok, who was intrigued and on board. “Luboshutz & Nemenoff’s” success came quickly, but it was their talent and chemistry that left an enduring legacy.

Marston’s 4-CD set contains Luboshutz and Nemenoff’s RCA Victor recordings and selections from their LP discs: Mozart’s Sonata K. 448, Brahms’s Haydn Variations, Schumann’s Andante and Variations, Op. 46, Milhaud’s Scaramouche Suite, and many transcriptions and arrangements. Also included are live performances of Bach and Mozart concerti with Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra, as well as Harl McDonald’s Two Piano Concerto with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by the composer. Notes are written by Thomas Wolf, the grandson of Lea Luboshutz and the grandnephew of Pierre and Genia. Thomas’s recollections of the time spent with his great aunt and uncle provide a unique glimpse into the people who comprised one of the greatest of piano duos.

CD 1 (77:43) | ||

MOZART | ||

| Sonata for Two Pianos in D, K. 448 | ||

| 1. | I. Allegro con spirito | 5:32 |

| 2. | II. Andante | 7:38 |

| 3. | III. Allegro molto | 5:55 |

| RCA Victor, 9 February 1940, New York City CS-042666-4, CS-042667-3, CS-042668-2, CS-042669-4, CS-042670-4 (17546/8 in album set M-724) | ||

MOZART | ||

| Piano Concerto No. 10 in E-Flat for Two Pianos, K. 365/316A | ||

| 4. | I. Allegro | 10:08 |

| 5. | II. Andante | 7:36 |

| 6. | III. Rondo: Allegro | 7:00 |

| with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Serge Koussevitzky concert performance recorded in Symphony Hall, Boston, 25 October 1938 | ||

CHOPIN | ||

| 7. | Rondo for Two Pianos in C, Op. posth. 73 | 8:52 |

| RCA Victor, 12 June 1945, New York City D5-RC-503-1A and D5-RC-504- 1A (11-9137 in album set M-1047) | ||

SCHUMANN | ||

| 8. | Andante and Variations in B-Flat, Op. 46 | 13:03 |

| RCA Victor, 11 June 1945, New York City D5-RC-497-1, D5-RC-498-1, D5-RC-499-1, D5-RC-500-2 (11-9135/6 in album set M-1047) | ||

MENDELSSOHN–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 9. | Allegro Brilliant in A, Op. 92 | 7:47 |

| RCA Victor, 12 June 1945, New York City D5-RC-505-1 and D5-RC-506-2 (11-9138 in album set M-1047) | ||

MENDELSSOHN–PHILIPP | ||

| 10. | Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Op. 61 | 4:09 |

| RCA Victor, 21 February 1941, New York City CS-060692-1 (11-8455) | ||

CD 2 (76:43) | ||

LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 1. | The Bat—A Fantasy from Johann Strauss’s Die Fledermaus | 9:34 |

| Everest LP SDBR 3076, circa 1959 | ||

RICHARD STRAUSS–BABIN | ||

| 2. | Waltzes from Der Rosenkavalier, Op. 56 | 5:09 |

| RCA Victor, 27 December 1949, New York City D9-RC-2125-2A (12-3079) | ||

WEBER–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 3. | Rondo from Sonata No. 3 in D Minor for Violin and Piano | 2:45 |

| Remington LP 199-143, circa 1952 | ||

MOZART–KONUS | ||

| 4. | Overture from Le nozze di Figaro, K. 492 | 3:47 |

| RCA Victor, 21 February 1941, New York City CS-060691- 2 (11-8455) | ||

ROSSINI–KOVACS | ||

| 5. | Largo al factotum from Il barbiere di Siviglia | 3:05 |

| RCA Victor, 12 June 1945, New York City D5-RC-501-1 (11-8987) | ||

HANDEL–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 6. | Passacaglia from Suite No. 7 in G Minor, HWV 432 | 8:03 |

| RCA Victor, 21 February and 3 March 1941, New York City CS-057672-3 and CS-057673-6 (11-8288) | ||

MILHAUD | ||

| Scaramouche, Op. 165b | ||

| 7. | I. Vif | 2:59 |

| 8. | II. Modéré | 3:56 |

| 9. | III. Brazileira: Mouvement de samba | 2:16 |

| RCA Victor, 1 June 1949, New York City D9-RC-1795-1A and D9-RC-1796-1A (12-1091) | ||

LEVITZKI | ||

| 10. | Valse tzigane, Op. 7 | 2:22 |

| RCA Victor, 8 February 1940, New York City BS-047023-1 (2096) | ||

DE FALLA–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 11. | Danza ritual del fuego from El amor brujo | 3:08 |

| RCA Victor, 8 October 1941, New York City BS-062730-7 (2214) | ||

KREISLER–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 12. | Tambourin Chinois, Op. 3 | 3:36 |

| RCA Victor, 12 June 1945, New York City D5-RC-502-2 (11-8987) | ||

GLINKA–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 13. | The Lark | 5:31 |

| RCA Victor, 3 March 1941, New York City CS-062727-1 (17993) | ||

CUI–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 14. | Orientale from Kaleidoscope, Op. 50, No. 9 | 2:58 |

| RCA Victor, 8 February 1940, New York City BS-042689- 2 (2084) | ||

STRAVINSKY–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 15. | Danse russe from Petrouchka | 2:32 |

| RCA Victor, 15 September 1939, New York City BS-042695-1 (2096) | ||

MUSSORGSKY–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 16. | Coronation Scene from Boris Godunov | 3:16 |

| RCA Victor, 8 February 1940, New York City BS-042688-5 (2084) | ||

SHOSTAKOVICH–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 17. | Polka from Age of Gold, Op. 22 | 2:35 |

| RCA Victor, 6 October 1941, New York City BS-067970-1 (2214) | ||

SHOSTAKOVICH–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 18. | Waltz from The Golden Mountains, Op. 30 | 4:29 |

| RCA Victor, 27 December 1949, New York City D9-RC-2124-1 (12-3079) | ||

RIEGGER | ||

| 19. | Finale from New Dance, Op. 18 | 4:43 |

| RCA Victor, 4 March 1941, New York City CS-060693-4 (17793) | ||

CD 3 (80:29) | ||

BRAHMS | ||

| 1. | Variations on a Theme of Haydn, Op. 56b | 15:45 |

| RCA Victor, 4 March 1941, New York City CS-057676-5, CS-057677-6, CS-057678-5, CS-057679-4 (18096/7 in album set M-799) | ||

BRAHMS | ||

| Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 52a | ||

| 2. | I. Rede, Mädchen | 1:08 |

| 3. | II. Am Gesteine rauscht die Flut | 0:41 |

| 4. | III. O die Frauen | 1:01 |

| 5. | IV. Wie des Abends schöne Röte | 0:39 |

| 6. | V. Die grüne Hopfenranke | 1:27 |

| 7. | VI: Ein kleiner, hübscher Vogel | 2:19 |

| 8. | VII: Wohl schön bewandt war es | 1:15 |

| 9. | VIII: Wenn so lind dein Auge mir | 1:11 |

| 10. | IX: Am Donaustrande | 1:49 |

| 11. | X: O wie sanft die Quelle | 0:55 |

| 12. | XI: Nein, es ist nicht auszukommen | 0:50 |

| 13. | XII: Schlosser auf, und mache Schlösser | 0:42 |

| 14. | XIII: Vögelein durchrauscht die Luft | 0:37 |

| 15. | XIV: Sieh, wie ist die Welle klar | 0:57 |

| 16. | XV: Nachtigall, sie singt so schön | 1:24 |

| 17. | XVI: Ein dunkeler Schacht ist Liebe | 1:06 |

| 18. | XVII: Nicht wandle, mein Licht | 1:51 |

| 19. | XVIII: Es bebet das Gesträuche | 1:14 |

| with the Victor Chorale, conducted by Robert Shaw RCA Victor, 24 May 1946, New York City D6-RC-5906- 2, D6-RC-5907-1A, D6-RC-5908- 2, D6-RC-5909-2A, D6-RC-5910-2A, D6-RC-5911-2 (11-9307/9 in album set M-1076) | ||

PORTNOFF | ||

| 20. | Perpetual Motion on Brahms’s Vergebliches Ständchen | 3:17 |

| Remington LP 199-143, circa 1952 | ||

BACH–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 21. | Sicilienne from Sonata for Flute and Klavier in E-Flat, BWV 1031 | 3:25 |

| RCA Victor, 12 September 1939, New York City CS-042671-1 (17548 in album set M-724) | ||

BACH–PHILIPP | ||

| Organ Concerto after Vivaldi in A Minor, BWV 593 | ||

| 22. | Allegro maestoso | 4:16 |

| 23. | Adagio | 4:42 |

| 24. | Allegro | 3:39 |

| RCA Victor, 31 May 1949, New York City D9-RC-1792-1, D9-RC-1793-1A, D9-RC-1794-1 (12-1169/70 in album set M-1378) | ||

BACH–LUBOSHUTZ | ||

| 25. | Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 61 | 4:45 |

| RCA Victor, 1 June 1949, New York City D9-RC-1795-1, (12-1169 in album set DM-1378) | ||

BACH | ||

| Concerto in C for Two Klaviers, BWV 1061 | ||

| 26. | Allegro | 7:24 |

| 27. | Largo | 5:32 |

| 28. | Presto | 6:40 |

| with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Serge Koussevitzky broadcast from the Tanglewood Music Festival, 15 July 1947 | ||

CD 4 (79:57) | ||

DEBUSSY | ||

| 1. | Lindaraja | 5:38 |

| Remington LP 199-147, circa 1952 | ||

SAINT-SAËNS | ||

| 2. | Danse Macabre, Op. 40 | 7:35 |

| RCA Victor, 29 October 1941, New York City CS-067982-4 and CS-068131-2 (18486) | ||

SAINT-SAËNS | ||

| 3. | Variations on a theme of Beethoven, Op. 35 | 15:55 |

| RCA Victor, 15 September 1939, New York City CS-042691-2, CS-042692-1, CS-042693-1, CS-042694-1 (15835/7 in album set M-638) | ||

KHACHATURIAN | ||

| Three Pieces for Two Pianos | ||

| 4. | Ostinato | 5:01 |

| 5. | Romance | 3:37 |

| 6. | Fantastic Waltz | 3:32 |

| Vanguard LP VSD 2128, circa 1962 | ||

REGER | ||

| 7. | Introduction, Passacaglia and Fugue, Op. 96 | 17:52 |

| Remington LP 199-143, circa 1952 | ||

MCDONALD | ||

| Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra | ||

| 8. | I. Molto moderato | 7:02 |

| 9. | II. Theme and Variations: Andante espressivo | 6:48 |

| 10. | III. Juarezca: Allegro | 6:58 |

| with the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by the composer broadcast from the Academy of Music, Philadelphia, 15 April 1944 | ||

Producer: Ward Marston

Associate Producers: Thomas Wolf and Scott Kessler

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston, J. Richard Harris, and Raymond J. Edwards

Photos: From the Luboshutz-Goldovsky-Wolf Family archive

Booklet Coordinator: Mark S. Stehle

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Booklet Notes: Thomas Wolf and Gregor Benko

Marston would like to thank Donald Manildi, Curator of the International Piano Archive at the University of Maryland, for providing excellent copies of the RCA Victor and Remington recordings included in this set.

Marston would like to thank Bridget Carr, Curator of the Boston Symphony Orchestra Archive, and BSO historian Kevin Mostyn for providing the recording of Mozart’s Concerto for Two Pianos, CD 1, Tracks 4-6.

Marston would like to thank Jason Coleman for providing off-the-air recordings of Bach’s Concerto for Two Pianos in C, CD 3, Tracks 26-28, and McDonald’s Concerto for Two Pianos, CD 4, Tracks 8-10.

Marston would like to thank Gregor Benko for his editorial guidance.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

A VERY BRIEF HISTORY OF DUO-PIANO PLAYING

by Gregor Benko

Duo keyboard playing began in domestic circumstances, but by the 1760s the prodigies Mozart and his sister Maria Anna were playing duo-harpsichord recitals across Europe. In 1781 Mozart composed his sonata for two pianos, K. 448, with which this CD compilation begins, for a performance with his pupil Josepha Auernhammer. It is arguably the cornerstone work of the duo-piano literature (and was the subject of a 1993 experiment that purported to show the now debunked “Mozart effect,” in which ten minutes of listening to the work was said to improve the listener’s mind).

The nineteenth century saw great composers writing masterpieces for two pianos, many of which can be found in this collection. At the same time, great solo pianists teamed to give duo-piano recitals, as when Moritz Rosenthal and his teacher Rafael Joseffy played duo recitals that would culminate in astounding feats, such as both playing a Chopin Etude in unison. By the 1920s duo-piano concerts presented by the Lhevinnes, Gabrilowitsch and Bauer, Beryl Rubinstein and Arthur Loesser, and others were occasionally heard, but it wasn’t until the end of that decade and the beginning of the next that professional duo-piano teams became a regular part of the concert scene, with the emergence of Bartlett and Robertson, Luboshutz and Nemenoff, and a bit later, Vronsky and Babin.

Since World War Two, concerts presented by both professional duo teams as well as star soloists working together have become commonplace, and the recordings made by the pioneer duos are now considered historic documents. The duo of Anthony and Joseph Paratore has been quoted: “One of our favorite duo-piano teams of the past is Luboshutz and Nemenoff. Their style of playing was unique in the way they handled ritardandi and rubati together.”

REMEMBERING LUBOSHUTZ & NEMENOFF

by Thomas Wolf

BACKGROUND

It is a lovely day in Rockport, Maine in the early 1950s where I am spending the summer in my grandmother’s house with my extended family. My grandmother is Lea Luboshutz, a concert violinist who taught for decades at the Curtis Institute of Music. She is now retired but she oversees the musical development of her flock, including me. Her house and many in the neighborhood were once part of a Curtis Institute enclave where teachers and students came to study and play concerts in June, July, and August. Nearby lives my great uncle, Pierre Luboshutz, and his wife, Genia Nemenoff.

Pierre and Genia have no children of their own and as a result, my five siblings and I are the beneficiaries. They spoil us. Today I am headed to their house for lunch and I will spend part of the afternoon there, something I do fairly frequently. We will eat a sumptuous meal cooked by my aunt, laid out in a formal dining area, on lovely china with polished silver. Nearby will be their beloved dog, Vodka, who Uncle Pierre has taught to jump up on her hind legs and “play” the piano. As with all their “pianist” dogs over the years, Vodka will be rewarded with a treat of buttered bread with jam.

As we sit down to eat, Genia complains as she always does that the food is not cooked as skillfully as it should be (“I am sorry, the lamb is overdone and stringy” becomes a family joke) but to my taste it is wonderful.

Though I am only in my early teens, we will talk as adults—about music, books, world events, and the family. Pierre will share some stories from their touring dates of the past year. Most will be very funny and he will tell them in his thick Russian accent and will laugh uproariously. Genia will comment on a recent concert I have given locally with my brother Andy, a pianist. While the rule is that concerts by family members are either, “good,” “wonderful” or “extraordinary” in any one of four languages (they are never bad), Genia and eventually Pierre will feel free to critique some of the phrasing or ensemble playing. I am a flutist and I have recently performed the Eb major flute sonata by J. S. Bach with its beautiful Sicilienne movement as well as the Scene from the Opera Orpheus by Gluck, pieces which Pierre has arranged for two pianos and which the two of them play often. Clearly, reading between the lines after the concert, my performance did not quite measure up in Genia’s opinion, but the criticism will be muted and mixed with praise.

In the afternoon, Genia will go practice (Pierre rarely does) and he and I will sit outside and share the previous day’s New York Times, which arrives in our town a day late, after which we will play a few rounds of ping pong. Though my game is getting better, I can never beat Pierre. His wicked serve is completely unpredictable and his nonstop recitation by memory of excerpts from the great classics of Russian literature (in Russian of course) is quite distracting. Soon we will head to Pierre’s sister Lea’s house (my grandmother). Her son, my uncle Boris Goldovsky, is up from Tanglewood where he heads the opera department, so we will meet up with other well-known musicians from the neighborhood who will talk shop and gossip and go for a swim. Before everyone arrives, Uncle Pierre will request that I row him around Rockport Harbor—a task I have been honored to fulfill since I was ten years old.

For me, these afternoons are part of the magic of my boyhood, memories that I would not trade for anything. Now more than sixty years later, they come back to me as I have the joy of listening to Uncle Pierre and Auntie Genia’s artistry on these CDs.

ANTECEDENTS

In many ways Pierre Luboshutz (1890–1971) and Genia Nemenoff (1905–1989) were very similar—musicians from Russian-Jewish backgrounds who had found success in America. But their differences were significant. For two generations, Pierre Luboshutz’s forebears had made a living—albeit a modest one—in the music business. Grandfather Luboshutz (actually Luboshitz in Russian) was a professional opera singer, Pierre’s father a violin pedagogue. The family lived in Odessa where their main source of income was a modest business, run by Pierre’s mother, buying and selling pianos.

By way of contrast, though Genia Nemenoff’s parents were accomplished musicians—her father a singer, her mother a pianist—neither was a professional. And unlike the Luboshutz family, the Nemenoffs were well off financially. Their affluence came from the retail fur trade, through a business begun by Genia’s mother’s family, the Jacobs, who had emigrated from Russia to Germany before Genia was born. In time, when Genia’s father Aaron Nemenoff married into Marie’s family, he gave up any thought of a musical career and was given the sinecure of the Paris branch of the family fur business. Thus, while Pierre Luboshutz grew up poor in Odessa far from the international musical capitals of Russia (Moscow and Saint Petersburg), Genia Nemenoff’s childhood was spent in an affluent milieu in one of the great cultural cities in the world.

For both families, anti-Semitism had significant consequences that shaped their lives. Russian laws established by Tsaritsa Catherine the Great (1729–1796) required that Jews live in what was called the “Pale of Settlement” (a large strip of land of which Odessa was a part). The only exceptions that allowed Jews to live in the great cities of Moscow and Saint Petersburg were either acquiring great wealth or displaying exceptional talent. Thus, for the Luboshutz family, raising superstar musical children who might become rich and successful and reside anywhere in the Empire became a singular obsession. Pierre’s two older sisters fulfilled their parents’ dreams. Lea, the oldest, a violinist, and middle sister Anna, a cellist, paved the way for Pierre, the third child.

Both girls were prodigies who had brilliant careers at the Moscow Conservatory, where each won a coveted gold medal and where both were selected for the international touring circuit even before graduation, appearing with the likes of Chaliapin, Scriabin, Koussevitzky, and others. By the time Pierre Luboshutz arrived in Moscow to attend the Conservatory, he was considered part of a distinguished musical family.

For Genia’s family too, anti-Semitism shaped their lives. While as wealthy merchants they were permitted to live in Saint Petersburg where Genia’s mother was born, constant harassment eventually drove them out of Russia and, in the case of Genia’s parents, on to France via Germany, both countries offering far more opportunities (and safety) for Jews. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Pierre Luboshutz would follow that same path—first from Moscow to Berlin and then to Paris—where he would encounter Genia Nemenoff, teaching her in a masterclass at the Paris Conservatory.

EARLY CAREERS, MARRIAGE,

AND CREATING A DUO-PIANO TEAM

Pierre’s path to that fateful masterclass where he met Genia had been circuitous at best and not nearly as distinguished as that of his sisters. He had never been one to enjoy long hours of practice and the life of a bon vivant in Moscow cut into his musical studies.

When he received only a silver medal upon graduation from the Moscow Conservatory, his parents were displeased. And his career as a piano soloist was short-lived. Rather, he became known primarily as an accompanist not only for distinguished musicians like his sisters, Serge Koussevitzky, Efrem Zimbalist, Gregor Piatigorsky, and Paweł Kochan´ski (Paul Kochanski) among many others, but also for the American dancer, Isadora Duncan. Duncan’s free-form dances to masterpieces of classical repertoire were so popular with Russian audiences that she was encouraged to establish a dance school in Moscow where Pierre also worked as an accompanist.

But perhaps his most important musical opportunity was provided by his more famous sisters through the eponymous Luboshutz Trio, a chamber group comprised of the three siblings that was among the most successful in Russia in the early teens of the twentieth century. On one tour alone, for example, the group played fifty cities during the winter months of 1913–1914 ending up with an important concert in the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory.

But if these professional experiences did not live up to the aspirations of Pierre’s parents, the nature of the intimate playing with one or two other musicians of superior gifts was perhaps the most valuable preparation Pierre received for what became his greatest later success as a musician—the duo-piano collaboration with his wife.

The piano duo of Luboshutz & Nemenoff, which would become among the most sought after in the world, was created almost by accident. Pierre and Genia continued to see one another in Paris where she was trying to make a career as a soloist. But Pierre was often away, touring in the United States in the 1920s, a land of great opportunity and lucrative fees. True, he was only an accompanist, but he was making a decent living and saving money when in Paris by living in an apartment with his sister Lea’s family. When Genia got her first big break—a tour in the United States in 1931—the two met up in New York, married three days after her arrival, and decided to make the United States their home. It made sense from many points of view. Pierre’s sister Lea had recently decided to move her family (including their mother) to Philadelphia where she was now a faculty member at the Curtis Institute of Music (her son and Pierre’s nephew, Boris Goldovsky, was a student there as well). It certainly looked as though the United States would be the new home for most of the members of the family who had left Russia (some, like Pierre’s cellist sister Anna Luboshutz, had chosen to stay in the Soviet Union). But more important, it seemed like America was the land of limitless possibilities. Pierre and Genia took an apartment in New York and began looking for work.

Unfortunately, the United States in the 1930s was not what it had been in the 1920s. The world-wide Depression was taking its toll on the music business. Happily for Pierre, the superstars with whom he was performing continued to secure bookings and provide him with a reasonable income. But for Genia, a little-known Parisian female pianist, her few opportunities were limited to some occasional teaching of mostly untalented pupils. After a full life with family in Paris and concerts throughout France, a New York apartment with long weeks without Pierre or anyone else close to her was lonely.

Genia’s letters to Pierre when he was on the road are heartbreaking to read and it was clear that America was not for her. In a letter of 4 March 1932, she writes of her horror about the kidnapping of the baby of the aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife Anne that had occurred three days earlier—it was front page news and impossible to miss. “It’s incredible,” she wrote, adding tellingly, “Such a thing could only happen in America.” Genia had lived through a tumultuous era in Europe but she had been surrounded by a loving family and doting parents who protected her. She often found America hard to understand and downright scary at times and she had always been emotionally fragile. Pierre, with his outsize personality, optimism, and good humor was her new protector … when he was around. But being alone in the United States was not working for Genia. Obviously, something had to be done if the two of them were to stay.

And it was Pierre who came up with the idea. Initially, it was simply that the two of them should make music together when Pierre was home. They explored the four-hand and two-piano literature and Pierre even tried his hand at transcribing some favorite pieces. As their musical circle grew, they would invite friends for dinner with Genia’s superb cooking and perform together afterwards. At one of these gatherings, the impresario Sol Hurok, who had been sister Lea’s manager and had become a friend of the family, was in attendance. Pierre talked about how sad it was that there was so little opportunity for music lovers to hear performances of the wonderful musical literature that existed for two pianos—compositions by Bach (if you counted the harpsichord music) as well as by Mozart, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Chopin, and many others. As they discussed it, Hurok mused that if Pierre and Genia were the ones performing this music, it could be an “attraction” that a good manager could sell. Here were two pianists with authentic Russian names—a handsome married couple—playing repertoire that was rarely heard, and it could be supplemented by Pierre’s arrangements—popular works like De Falla’s “Ritual Fire Dance,” Glinka’s “The Lark,” and melodies from Johann Strauss’s opera, Die Fledermaus. It was a relatively open niche. Why shouldn’t Pierre and Genia fill it?

It wouldn’t hurt that Pierre’s sister Lea had already scored many successes in America as a solo artist with orchestras and as a recital partner with the great pianist, Josef Hofmann. Many of those who presented her might take a chance on Pierre and Genia. Then there was Koussevitzky, Pierre’s old recital partner. Once a double bass virtuoso, he was now Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. He could certainly put in a good word with important presenters and even hire Pierre and Genia to solo with his orchestra in the future. Hurok thought they had a chance at a career and offered to get them started with a few concerts and a New York debut recital.

THE DUO-PIANO TEAM OF LUBOSHUTZ & NEMENOFF

The duo-piano team of Luboshutz & Nemenoff was an instant success. Hurok’s imprimatur was helpful, of course, as were Lea’s many contacts. And though in time they did have quite a bit of competition as more pianists toured and recorded as piano duos, many of these duos were part-time, made up of pianists who had careers as soloists, while in Pierre and Genia’s case, they devoted themselves full time to playing together. As solo pianists they would have been overwhelmed by big names, but as a duo-piano team, they had more of a chance to shine. Good reviews became standard fare and the bookings increased exponentially.

Pierre, Genia, and their management team agreed that their first concert together should be out of the limelight in a place where a program could be tested with a live audience without prominent critics around. Thus, on 15 October 1936, a concert was arranged in South Bend, Indiana. It was a resounding success. Their New York debut was three months later on 18 January 1937, and they received the desired quote from the New York Times that could land directly in their publicity material (“Duo art of a high order”). A subsequent New York Times review by Noel Straus read, “This reviewer has never before known two-piano artistry comparable to this.” And so it replaced the 1937 review in their publicity materials.

Hurok’s promise of concert dates was no idle prediction. During that first season (an abbreviated one of less than three months), they played twenty-four concerts and the Musical Courier captured them returning after the tour.

During the next three seasons Pierre and Genia appeared 198 times, including their promised prestigious first appearance with Serge Koussevitzky and his Boston Symphony Orchestra. It seemed appropriate that the man who had given Pierre his first solo concerto appearance in 1915 should provide Luboshutz & Nemenoff one of their first big breaks in America. Other major orchestras liked the novelty of exotic duo-piano soloists and began to book Pierre and Genia regularly. They were especially popular with the Philadelphia Orchestra, with which they played a remarkable number of concerts, given the limited repertoire. In time, they were playing as many as 100 concerts a year, including tours of Europe, Central and South America, and South Africa. When they appeared under the baton of Arturo Toscanini, their publicity material reflected the fact that they were the only duo-piano team to have done so.

THE PIANO CHALLENGE

One of Pierre and Genia’s challenges was finding venues on the road that could easily provide two grand pianos. Pierre had always been a Steinway artist but the company had no interest in helping solve the problem. The Baldwin Piano Company, on the other hand, was constantly searching for artists to endorse its product and was willing to guarantee two grands at any venue that booked Luboshutz & Nemenoff in the United States so long as the team would become exclusive Baldwin artists. In time, the company would also provide six pianos for their personal use, instruments that were replaced every five years. Three pianos went to their large New York apartment and another three went to Pierre and Genia’s summer residence (“Twin Keys”) in Rockport, Maine. This would allow Pierre and Genia to practice separately in the morning in different locations and then rehearse together on two pianos later in the day without having to leave home. Some of those pianos still reside in the homes of Pierre and Genia’s grand nephews and nieces.

Despite the association with Baldwin, one of Pierre and Genia’s early publicity photos shows them sitting at two Steinway pianos. Whether anyone at Baldwin ever caught this mistake is unclear. What is clear is that this rare photo was soon pulled from circulation.

BEAUTIFUL PLAYING, WONDERFUL REVIEWS

Many things helped Pierre and Genia establish themselves among the top rank of touring soloists. While certainly I am biased, to me they played extraordinarily beautifully, creating an incomparable sound, like silk. One piano can sound harsh, two pianos can sound downright ugly. But even when the music called for top volume, Pierre and Genia’s playing was simply gorgeous. Studio recordings cannot do justice to their remarkable sound, but as I have listened to the live recording of the Mozart concerto in this collection, I am occasionally brought back to this special magical sound in the many concerts of theirs that I attended. If I had to choose a handful of concerts from the past that I would want to attend once again, a concert by Luboshutz & Nemenoff would be on that list.

Another reason for their success was that they received consistently positive press and excellent reviews. They took every opportunity to get exposure, even to the extent of posing on horseback in a photo staged by my father, taken by one of my father’s cousins, and sent to the magazine, Musical America.

When it came to reviews, musician members of the Luboshutz family privately regarded critics as largely ignorant and musically unreliable. But they knew how important good reviews were to establishing a career. They also knew that for better or worse, critics have something of a herd mentality, generally following the lead of the most influential writers among them. Pierre and Genia worked hard to secure good reviews early from those that mattered. The gold standard in the United States was an enthusiastic review from the New York Times, and Pierre and Genia considered themselves fortunate in getting several strong ones. An early brochure quoted one: “Extraordinary! Rarely are such heights of virtuosity reached in two piano playing!” After a while, it seems they were getting ecstatic reviews everywhere, like this one after a concert in Atlanta on 22 January 1941 that was quoted in their promotional material: “It is a rare occasion when an entire audience almost goes wild with enthusiastic appreciation of a concert, but that is what happened last night. There seemed to be not a single soul that did not enjoy every minute of a concert that was packed with artistic thrills.” The reviewer then goes on at length to enumerate all the reasons why Pierre and Genia had “perfected the art of two-piano playing to a higher degree than has ever been heard here.”

Pierre and the management team were also careful in the early days of the Luboshutz & Nemenoff career to garner quoted comments from distinguished musicians, which were placed prominently in their publicity materials. “Perfection in Two Piano Playing,” Serge Koussevitzky was quoted as saying at a time when he was considered one of the reigning maestros. With such statements, and with the great reviews from top-flight critics, lesser critics were loath to give Pierre and Genia negative reviews and to be honest, hard as I searched, I was unable to find one.

One of the most amusing reviews was quoted in a Luboshutz & Nemenoff brochure with the headline:

“DON’T GO AND PUT YOUR FOOT IN IT!” BOOK LUBOSHUTZ & NEMENOFF

Below, the brochure reproduced a review from the 23 January 1943, Boston Herald Traveler, beginning with the words “Some weeks ago when [name blocked out] appeared in recital here, we had to go and put our foot in it by announcing that the woods are full of duo pianists. … It seems that the woods also contain Luboshutz & Nemenoff and after hearing them on their second visit to Boston yesterday, there is nothing to do but start over again and say that … in many ways, this piano team is the most musically rewarding of all which practices the art today.”

ARRANGEMENTS AND NEW WORK

There was no way that Pierre and Genia could go back repeatedly to communities unless they had fresh repertoire and there were simply not enough original pieces for two pianos to do so. Ever resourceful, Pierre worked hard on musical arrangements (many of which are heard in these recordings) and wrote a few original compositions as well like the song “In Springtime” based on a poem by Aleksey Tolstoy. These not only gave the team more music to play but it enhanced the Pierre Luboshutz brand among the large group of amateur musicians who made up the concert ticket-buying public. The works that Pierre transcribed were chosen carefully based on popular tastes and many were not that difficult to play and were aimed at the amateur market (examples I mentioned earlier—the Sicilienne from J. S. Bach’s Eb major flute sonata and the Scene from the Opera “Orpheus” by Gluck that had previously been arranged for flute and piano by Georges Barrère—are good examples). Pierre was not above lifting arrangements that had been made famous by other instrumentalists like flutist George Barrère and violinist Fritz Kreisler and rearranging them for two pianos (though in the case of Kreisler, he secured permission first1). Another such “re-transcription” was the Rondo by Carl Maria von Weber found in this collection of recordings. It was originally a movement from one of Weber’s violin sonatas that was first transcribed for cello and piano by Pierre’s recital partner from earlier days, Gregor Piatigorsky. Pierre dedicated this later arrangement to Piatigorsky who had previously recorded his version for RCA Victor.

But the pressure kept increasing for Pierre and Genia to augment their list of musical offerings. When Pierre ran out of his own arrangements, and a punishing performance schedule prevented him from making a sufficient number of new ones, he asked his nephew Boris Goldovsky to help out. I found two of Boris’s arrangements in a program from Pierre and Genia’s 1940–1941 season—the Overture to Mozart’s Marriage of Figaro and Bach’s Chorale Prelude “Ach wie flüchtig.”2 A generation later, as purists began to dominate taste-making in classical music, it would have been unusual to find major artists shamelessly adapting the masterworks in this way and performing them in important venues. But at the time Pierre and Genia were touring, it was the norm, allowing them to always offer something new.

Other composers also arranged and wrote pieces for Luboshutz & Nemenoff, including a suite from the ballet “On Stage” by Norman Dello Joio, and new concertos for two pianos and orchestra, one by the Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu˚, and another by Vittorio Giannini. The premiere of the Martinu˚ by Pierre and Genia with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra on 5 November 1943 was considered important enough to be mentioned in the 8 November 1943 issue of Time magazine. Unusual for a new composition, it was so well received (reviewer Linton Martin called the premiere “a super event of the symphony season”3) that Ormandy invited them back to Philadelphia to play it again with the orchestra five years later.

Not every premiere was well received. Initially less successful was a work dedicated to them, the “Tzigane Waltz” by Mischa Levitzki (played in Carnegie Hall on 4 January 1938). Despite a mediocre New York review, Pierre and Genia decided to keep the piece in their repertoire—a wise decision given that audiences seemed to love the piece (a recording of it can be found in this collection).

Another work that received a mediocre reception was a concerto by a young Frenchwoman Claude Arrieu, performed later in 1938, also in New York. Pierre and Genia had known Arrieu at the Paris Conservatory and they agreed to play the first public performance of her concerto in New York’s Town Hall on 25 November 1938. The New York Times critic (Noel Straus) called it “a shallow concoction.” Another critic, Samuel Chotzinoff, wrote that “when original music is forthcoming, as it was last night with Mr. [sic] Arrieu’s Concerto, one is forced to conclude that arrangements of old stuff are the better part of valor.” Though the music was reviewed poorly, Luboshutz & Nemenoff were praised. To the best of my knowledge, after an initial performance of the Arrieu concerto, it was dropped from Pierre and Genia’s repertoire as they continued to refine their selections to meet the tastes of audiences and critics.

1 A program from 9 November 1942 at Westchester State Teachers College includes Pierre’s arrangement of Kreisler’s “Tambourin Chinois” and the program indicates that it was “with Mr. Kreisler’s permission.”

2 Program from the Civic Music Association (Chicago).

3 The Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 November 1943.

HARD WORK

Of all the factors contributing to their success, I think the most important was that Pierre and Genia were willing to work very, very hard and Genia probably deserved most of the credit. Pierre had never been a hard worker and without Genia, he probably would have been satisfied with a career that depended on others for the heavy lifting, those whose fame was already established. It had been that way in his relationships with Isadora Duncan, with Koussevitzky, with Zimbalist, and with Piatigorsky—all big names for whom Pierre played. They and their managers had taken care of all the non-musical things that kept them on top and Pierre could coast in their wake. Now Pierre and Genia had an opening to be the featured artists and they took advantage of it, but it meant far more effort and a greater attention to business. Though Pierre still didn’t practice long hours, both he and Genia rehearsed constantly, learning new repertoire and refining their ensemble playing. Pierre also spent considerable time on his arrangements while Genia wrote thank you notes and shopped for gifts to send to presenters large and small.

They were extremely gracious about interviews and the two of them—he with his Russian accent, she with her French one, and both with their old-world charm—were catnip for reporters. One of the more amusing stories about their willingness to be interviewed comes from David Ewen’s book, Listen to the Mocking Words: A Medley of Anecdotes about Music and Musicians:

The two-piano team of Luboshutz and Nemenoff were scheduled to give a concert in a small New England town. A few hours before the performance, they were approached for an interview. Hardly had they finished this chore when another such request came—then a third—and a fourth. At last Luboshutz asked one of the young men curiously, “Are there, then, so many different papers in this town?” “Oh, no,” he answered. “You see—we’re not really newspapermen at all. Just students in the journalism class, practicing interviewing!”4

One can also see evidence of their work ethic in the touring itineraries that they maintained for years. Touring was not easy in those days but Pierre and Genia seemed willing to go anywhere at any time. They had no children, which helped, but it is rather astonishing to realize just how many concerts they played each year—two hundred concerts in the first three seasons and upwards of a hundred a year thereafter. This was a large number in an age before air travel was common and when summer festival bookings were few. At the same time, they were constantly learning and memorizing new repertoire (unlike other piano duos, they played everything by memory). As an example, while other major soloists might carry a single new concerto in their repertoire in a season, Pierre and Genia carried two. Just two days after they premiered the Martinu˚ concerto in Philadelphia, they again appeared with the orchestra playing another relatively new piece—a concerto by Harl McDonald composed in 1937 (a recording of a subsequent performance is included in this collection).

High profile events were frequent. There was the annual recital in New York and regular appearances with the top orchestras in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia (including an incredible nine appearances with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra in the 1943–1944 season alone). But the bread and butter of their income came from concerts in countless smaller communities. They seemed to live on trains.

A typical page from one of their itineraries had them taking a train from New York to Washington where they played a concert, then leaving the next day for Asheville, North Carolina and Spartanburg, South Carolina, for concerts over the next two nights. The next night they were in Atlanta for a concert, then back to New York, and then off to Pittsburgh for a rehearsal and performance with the orchestra there. They even put an off day to good use during this period. My parents, who lived outside of Philadelphia, had received an official looking letter from the management office saying that after Pierre and Genia played with the Baltimore Symphony on November 24th, they would take the train so they could spend time with their niece and nephew and catch up with their grand nephews and nieces. They would then return to Baltimore on November 26th to play a second concert with the Baltimore Symphony. It helped that my parents had three Steinway pianos in the house—two in the large living room and one upstairs—so that Pierre and Genia could practice separately and together during the day. The letter stated: “They will arrive at about Noon and leave at 11:00 a.m. of November 26th. Will you please confirm the reservation.” Reading the somewhat confusing listing of times noted in the penultimate sentence, my father quipped, “Pierre and Genia are so amazing that they can leave an hour before they arrive!”

Only in the summer would Pierre and Genia relax in Maine where they and other members of the family owned property. Except for the occasional concert at Tanglewood with the Boston Symphony or at the Robin Hood Dell with the Philadelphia Orchestra, they took the summer off.

4 David Ewen, Listen to the Mocking Words: A Medley of Anecdotes about Music and Musicians, New York: Arco Publishing, 1945, pp. 57-58.

THREE PIANOS AND PIERRE CONDUCTS

Once Pierre and Genia established their reputations as Luboshutz & Nemenoff, they decided that they would appear on stage only together. Pierre gave up his former career as an accompanist and Genia never sought a solo concert again. One work involving the two of them that required a collaboration was Johannes Brahms’s Liebeslieder Waltzes that includes a vocal ensemble. They performed the work many times with numerous people including with Robert Shaw and the Victor Chorale, a version that was recorded and is included in this collection. From an audio perspective, the result was not entirely successful. Though they never said anything to me about it, I suspect that Pierre and Genia were not especially happy with the recording as it was one of the few that they did not send as gifts to family members and I only learned about it many decades later.

There was another format that allowed them to play together involving an additional featured artist. They could appear with a third pianist, though they made it a rule that it always had to be a family member so as to be able to graciously refuse others who might ask.

There were two instances of this arrangement that became part of the Luboshutz & Nemenoff story—one humorous, the other more serious. With their growing fame, one particular family member was taking a special professional interest in Pierre and Genia’s success—Pierre’s uncle, Mischa Katzman, who had shortened his surname to Katz after he came to America and settled in San Francisco. He had learned the piano business from his older sister, Katherine Luboshutz, Pierre’s mother, while a boy in Odessa, and had put the lessons to good use. He established a very successful shop and made special arrangements to supply pianos for Pierre and Genia’s concerts in San Francisco.

Uncle Mischa enhanced his reputation by claiming that he too was an accomplished pianist (in fact, he could barely play simple melodies). He even told customers that he appeared from time to time with his famous nephew and his wife. When they next came to San Francisco, Mischa promised his customers, he would be on the program. When all of this was explained to Pierre, he was astonished—especially when Mischa begged Pierre to let him appear for one number at a San Francisco concert. Mischa had already figured out how this could work. There would be three pianos on stage. Two would be placed normally (facing one another along the front edge of the stage with the players sitting sideways to the audience). Mischa would place the third piano with its keyboard facing to the back of the hall and he would sit at the keyboard facing the audience. In this way, it would be impossible for anyone to see his hands and realize that he wasn’t playing, especially if he swayed his body in a way that looked convincing.

Why Pierre and Genia ever agreed to this, I will never know. Perhaps Pierre’s mother, now in America and still a dominant presence in the family, put pressure on Pierre—after all, this would be good for Mischa’s business. And why the local music critic didn’t notice anything untoward is also difficult to understand—though Pierre claimed it told you a lot about the musical knowledge and sensibility of those who review concerts. But the ruse was successful. Mischa appeared during only one short piece and the applause was impressive with Mischa’s customers shouting “bravo.” Pierre made clear to Uncle Mischa that this would never happen again and it didn’t. After all, Mischa had gotten what he needed—a public performance with Pierre and Genia that he could brag about for the rest of his life.

The other occasions that included three pianos involved Pierre’s nephew and my uncle, Boris Goldovsky. Pierre had been Boris’s first piano teacher in Moscow and Boris had been playing professionally from the age of eleven. In time, his primary career shifted from pianist to opera impresario though he continued to play piano recitals and appear as a soloist with orchestras from time to time. He and Pierre had spoken many times about some sort of three-piano concert, but the concept had not gone much beyond idle chat. On one occasion, it looked like there was a possibility. Pierre and Genia were scheduled to play at Tanglewood—the summer home of the Boston Symphony—where Boris headed the opera department. The program was entirely devoted to the music of J. S. Bach and since there are Bach concertos for three keyboards, it seemed like a perfect occasion for a collaboration. But Serge Koussevitzky, who planned the program and was conducting it, nixed the idea.

Then in the early fifties, Boris came up with an idea that the management thought was quite attractive and would be popular with buyers—an all-Mozart program that featured his concerto for three pianos to coincide with a Mozart bicentennial.

The bicentennial of Mozart’s birth was in 1956 and since Mozart had written concertos for single piano, two pianos, and one for three pianos, why not put together a program that included one of each? Pierre and Genia would play the duo-piano concerto, of course, and Boris could conduct the orchestra. The three of them would play the triple concerto and since the third piano part was fairly easy, Boris could conduct from the third piano stool. Boris could be soloist in the single concerto. But he would need someone to conduct the orchestra. After much cajoling, he convinced Pierre that conducting a Mozart concerto was easy and promised to teach him. Initially skeptical, Pierre practiced diligently. He and Boris spent many hours during the early weeks of the summer of 1955 in Rockport studying the score of the Mozart concerto, listening to the recording and mastering conducting technique. Pierre had to be ready for the rehearsals for the first “preview” concert, as they were billing it, and it was no joking matter—an appearance at Lewisohn Stadium in New York (capacity 8000) was scheduled for July 27th.

One of my favorite family stories centered around those weeks when Pierre was perfecting his conducting technique. Boris and Pierre spent plenty of time together with Boris coaching. But at other times, Pierre practiced his conducting alone, often with a recording. On one occasion, he had been at it a particularly long time and Boris decided to go over to Pierre’s studio to see what his uncle was up to. Standing quietly outside, Boris heard Pierre speaking very loudly. “Violins … at measure twenty-one, second beat … it is sharp. Violas … next measure, the accent is late. Celli … at B, you are too loud and it should be more ponticello. Woodwinds, at C … you are not together with the piano with the eighth notes.” Pierre, who was talking to a bunch of chairs, was getting more and more worked up. Finally, he slammed his baton on his conductor’s stand and practically yelled: “Gentlemen, gentlemen. Must I explain and correct everything?” Boris decided that Pierre was now a genuine conductor.

Boris’s impression that Pierre was well prepared was borne out by the rehearsals and the initial concert. Lewisohn Stadium was packed. Pierre told the audience that back in Russia he had studied conducting with Koussevitzky when the two had toured together on a barge on the Volga. Whether true or not, Francis Perkins, the critic for the New York Herald Tribune, mentioned this in his review on 28 July 1955. He added that Pierre “showed a flair for the baton last night in a well-defined, dynamically sensitive orchestral interpretation of the G-major concerto [of Mozart].” The New York Times critic, Harold Schonberg, was more careful about Pierre’s possible experience, simply saying that “if memory serves, he [Luboshutz] has never been seen in this city in the role of a conductor.” But he too was complimentary, writing that Pierre “made a decidedly favorable impression on the podium. His tempos were unhurried but never flabby, he had things under control and his ideas about phrasing were always sensitive.” More important than the critics for the smooth workings of the tour, the musicians loved Pierre—it helped that he and Genia were superb pianists and as fellow instrumentalists, the orchestra members respected their musicality. They were willing to cut Pierre some slack as a conductor.

There was one amusing twist to the promotion for the tour. Pierre had insisted that if he was going to conduct, there needed to be a publicity photo of him doing so. Boris objected, saying that that would exclude Genia since the concerto Pierre was conducting had only one piano. Never one to be foiled by such details, Pierre decided the photo should include Genia anyway and so it came to be.

The three pianists played a second preview concert in Boston’s Symphony Hall with members of the Boston Symphony making up the orchestra players for this single event on 18 January 1956. Boris’s opera company sponsored the concert and it was a gala affair. Governor Christian Herter and his wife, Ambassador and Mrs. Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., Senator and Mrs. Leverett Saltonstall, Senator (soon-to-be President) John F. Kennedy and his wife, Charles Munch (the conductor of the Boston Symphony), Serge Koussevitzky’s widow, Olga, and Lea, Pierre’s sister, all served as Honorary Sponsors. Afterwards, the tour began in earnest. Reviews were uniformly positive but one of the ironies is that Pierre often received the majority of positive comments and he was now fully basking in his new role as a conductor.

Such was not the case when they played at Tanglewood on 13 July 1956, however, with the Boston Symphony. This would be Boris’s night. The concert had been scheduled to take place in the smaller of two concert venues with the overflow crowd (if there was any) to sit on the lawn. Perhaps because the local audience had been coming to Boris’s opera productions for years, many were curious to see him in the different role as a piano soloist, a concert orchestra conductor, and someone who could do both at the same time in the three-piano concerto. To the organizers’ surprise, nearly 2,500 people showed up—many more than the hall could accommodate. As bad luck would have it, pelting rain made it impossible for anyone to sit outside. So the concert was moved at the last minute to the much larger Tanglewood Concert Shed. If there was any doubt about who was the center of attention, New York Times reviewer, John Briggs, settled the question.

“Mr. Goldovsky was the center of interest at tonight’s concert, and gave a highly credible account of himself. As a part-time pianist, so to speak, he directs the New England Opera Company during the winter and stages opera at Tanglewood in the summer. Mr. Goldovsky, however, somehow finds time to keep his fingers in excellent performance condition.

“Conducting from the piano is a tour de force ventured by only a few conductor-pianists of our time. To be concerned in addition with two other soloists, interweaving Mozart’s tightly wrought music with them as well as keeping the whole performance going, is quite an impressive feat. The experience and assurance gained by Mr. Goldovsky as an opera conductor obviously stood him in good stead tonight.”

This time, to his chagrin, Pierre’s role as a conductor was hardly mentioned.

THREE-PIANO REPRISE AND

A DOG STEALS THE SHOW

The three-piano Mozart tour was so successful that the management begged the three pianists to come up with something similar for the 1958 season. They complied and once again, Pierre had the opportunity to do his share of conducting and this time, he had taken on the greater challenge of leading the orchestra in a Shostakovich concerto, with Boris playing the piano solo. Then they switched roles with Boris conducting and Pierre and Genia performing the Martinu˚ concerto that had been written for them. Also on the program was a triple concerto by Bach and for the grand finale, Pierre had arranged—in a three-piano version—his ever popular “Fantasy” based on themes from Johann Strauss’s opera Die Fledermaus (the two piano version is contained among the works in this CD set). Once again, the critics praised Pierre’s conducting. In only one concert, a major appearance in Philadelphia, was he upstaged and this time it was by his pet dog, “Vodka,” who was travelling with them. Somehow Vodka escaped from the dressing room and came on stage during the performance.

“Mutt Butts In on Masters’ Bach,” read the headline from Samuel L. Singer’s review in the Philadelphia Inquirer the next day. “The scene stealer,” he wrote, “was Vodka … who walked out on stage … calmly surveyed the scene, then settled quietly at Miss Nemenoff’s feet for the rest of the concerto. Nobody, including Luboshutz’s nephew, Boris Goldovsky, who was conducting from the third piano, missed a beat.” For the first time in decades of touring, it was not Pierre and Genia or Boris who managed a photo in the newspaper beside a concert review, but rather a canine lying happily below the keyboard.

RETIREMENT

In 1960, Pierre turned seventy and already there was some slippage in his playing and a few signs of memory problems. Most likely it was the early stages of the Parkinson’s disease that eventually led to his death just over a decade later. The grueling concertizing would have to be moderated. But what to do? Like so many musicians, Pierre and Genia had not planned for retirement. Though they had earned a good deal of money during their career, they had led a more-than-comfortable life with a summer estate, lavish entertaining, gift giving, and many other luxuries. Consulting with their nephew, Boris Goldovsky, who was well connected in the music business, Pierre and Genia agreed to head the piano department at Michigan State University in East Lansing while reducing the concert load. The five-year appointment at the university lasted from the fall of 1962 through the spring of 1968 and it was not a happy one. For one thing, it was not as prestigious as a possible conservatory position might have been, but this was not about prestige, it was about income and conservatories paid far less. University jobs like this one compensated their professors reasonably well and there was the possibility of vesting in a state pension plan if they stayed long enough. Predictably, Pierre and Genia, who had lived in cities like Paris and New York and had a wide circle of European friends, were not happy there—Pierre quipped that winters were colder than Siberia. Their students, for the most part, were not especially gifted and being far away from family for the first time was disorienting. After the initial appointment, they returned to New York, in part because Pierre’s illness had become worse. His death came in 1971.

Genia, who was almost fifteen years younger than Pierre, lived on for almost two decades alone in New York. She had lived, loved, and worked with one man for most of her adult life and now he was gone. They had had no children. Genia had lost both her parents in the Holocaust in the gas chambers of Auschwitz, something that continued to haunt her into old age as she often wondered if she could have done more to save them. There were few living relatives on the Jacob-Nemenoff side of the family and in any case, they lived abroad. Being financially dependent on Pierre’s relatives only exacerbated her unhappiness. In time she sold the house in Maine and became quite aloof and isolated. It was a sad end for someone who had been beloved by so many people for her great gifts and her generosity of spirit. Upon her death in 1989, she was buried next to Pierre in the Seaview Cemetery in Rockport, Maine.

RECORDINGS AND A LEGACY

Composers leave behind a body of work that contributes to their legacy. But performers create work in the moment and then it is gone. Except for recordings and perhaps their students, they leave little in the way of a tangible legacy. Thus, imperfect as they may be as a substitute for live performances, recordings are what we rely on in order to connect to those performers who are no longer with us. As the passion for historical recordings has increased and the technology to produce them has improved, we can get a little closer to those whose work was so treasured during their lifetimes.

Early on, Pierre recognized the importance of recordings in enhancing careers. Today, given the complete collapse of the classical recording business, it is sometimes difficult to remember that recordings were not only hugely important in popularizing classical performers but also produced substantial income for those artists who made them. Pierre and Genia recorded frequently under various labels. By 1943, they were recording for RCA Victor, which often took out large ads for their records in programs and magazines. A double-page RCA spread in a 13 and 15 July 1947, Tanglewood program features photos of Pierre and Genia along with Koussevitzky as RCA recording artists. These ads were still appearing more than a decade later. Another full-page ad in a Philadelphia Orchestra program from 25 and 26 March 1949, featured their photo and a list of four of their RCA Victor records above a photo of Eugene Ormandy with a list of some of his recordings with the Philadelphia Orchestra. They and their recordings were keeping good company.

But there was an important reason why their records were so popular. RCA Victor got it right: for the first time, you could hear great artists like Luboshutz & Nemenoff at your leisure in your own home. This new opportunity, that today we take for granted, introduced many new fans to classical music and changed the listening habits of those who were already experienced concertgoers.

All this Pierre and Genia knew. But one thing that they probably did not think much about at the time was that their recordings would be their single most enduring memorial for subsequent generations. Today, few people know the names Pierre Luboshutz and Genia Nemenoff and even fewer have heard the recordings. How fortunate that Ward Marston has chosen to reissue the Luboshutz & Nemenoff discography and contribute to their wonderful musical legacy.

These liner notes were written by Thomas Wolf, grandnephew of Pierre Luboshutz and Genia Nemenoff. Some of the material is adapted from his book, The Nightingale’s Sonata: The Musical Odyssey of Lea Luboshutz. Many thanks to Gregor Benko who gave general advice and provided material for these notes and to Scott Kessler who assisted in other aspects of the project.

With recordings drawn from several sources, our compilation of Luboshutz and Nemenoff includes many examples which are artistically remarkable, and we remain proud to be able to share the legacy of this wonderful musical team. Nevertheless, judged solely from a sonic standpoint, not all are remarkably good examples as recordings. On the one hand, there are some that are notable both for their artistry, provenance, and sound. One that stands out to our ears is the live 1938 performance with the Boston Symphony Orchestra of Mozart’s two-piano concerto, recorded inside Symphony Hall by a gentleman named Vos Greenough. The orchestra was not broadcasting that year (the NBC network now had its own orchestra, founded a year earlier) and it was generally accepted that there were no recordings of Boston Symphony performances from that time, as there were no broadcasts. Recently, however, out of the blue as it were, this recording was discovered and made available to us by Kevin Mostyn, the noted scholar of Boston Symphony history. Greenough (who was soprano Beverly Sills’s brother-in-law) seems to have been a Boston Symphony “insider” and apparently had permission, as well as the knowledge and equipment. Recorded with two disc-cutters running sequentially, no music was lost when the space on each disc reached its time limit. One deficiency is that the microphone placement was poor, resulting in a “boomy” sound as bass resonances overpowered the sound picture, especially when the tympani were playing. Compensating for that, the microphones were out front and not placed too near to the pianos—distant enough to give the listener the illusion of being in the hall, and providing a wonderful sense of balance between the orchestra and the pianos. A recording of a 1944 broadcast performance of the concerto with the same forces exists, but we felt this recording was more revealing of the pianists’s actual sound and artistry.

On the other hand, there were a number of recordings that did not measure up to this standard. Many of Luboshutz and Nemenoff’s finest recorded performances from an artistic standpoint were incised on 78-rpm discs by RCA Victor. A few of these, such as the Saint-Saëns’s Variations on a Theme of Beethoven and the Mozart two-piano sonata, are masterful performances with adequate sonics, while others suffer from the company’s use of a too-small studio and overuse of electronic compression, not allowing the music to breathe. We can only speculate why the company recorded in this way. Perhaps RCA during the 1940s was trying to produce a sonic picture as “forward” as possible (with microphones close to the instruments), which would have sounded good on the playback equipment of the day.

Other companies like British Columbia were making excellent piano recordings at the same time and never tried to do what RCA attempted—and ultimately failed—to accomplish in our view. From the start of electrical recording, RCA had always tried to record the instrument in too small a space. Compare Godowsky’s and Rachmaninoff’s Chopin Sonata and Carnaval recordings, made at approximately the same period by British Columbia and Victor respectively—only the Godowsky piano sounds like a piano in a hall. Polydor piano records from the same period also sound far superior, partially because of the hall resonance we can hear. Josef Lhevinne’s 1935 RCA discs also do not have “space” around the piano but are adequate. The situation appears to have worsened during the early 1940s. The culprit may well have been Charles O’Connell, RCA’s head of artists and repertoire from 1930 to 1944 (we know from his autobiography that he felt disdainful of pianists like Rachmaninoff, Schnabel, and Hofmann). During the war the Rachmaninoff recordings from Los Angeles and some of the Luboshutz/Nemenoff recordings have the sound “pushed forward” as far as possible. The company’s use of extreme compression became even more egregious after the war and the worst sounding of the Luboshutz and Nemenoff recordings, in our view, are Brahms’s Libeslieder Waltzes and the Bach-Vivaldi organ concerto.

Technology cannot undo compression nor compensate very much for the use of small recording rooms and too-close microphone placement, but we have done all that is possible to alleviate sonic shortcomings and present these recordings in the best transfers we could achieve to be able to share the artistry of Luboshutz and Nemenoff.

Why Should We Listen to Old Recordings (or Any Recordings for That Matter)?

Thomas Wolf, grand-nephew of Pierre Luboshutz & Genia Nemenoff, offers a cogent analysis of what we can learn from listening to old recordings. His reprinted blog can be found here.

THE ORIGINAL ARTICLE BY THOMAS WOLF AND THE ACCOMPANYING UNIQUE LIVE RECORDING OF MOZART’S TWO-PIANO SONATA FROM RADIO STATION WQXR CAN BE FOUND AT www.nightingalessonata.com/blog/2021/10/13/why-should-we-listen-to-old-recordings-or-any-recordings-for-that-matter-by-thomas-wolf

Luboshutz and Nemenoff: The Art of Duo-Piano Playing [pdf]

Luboshutz and Nemenoff offer artistry on the highest level, and I am thrilled to have discovered them, thanks to the indefatigable Ward Marston. The booklet notes are superb (except for the lack of the arrangers’ full names). An essay by Thomas Wolf, who is related to Luboshutz, is both instructive and touching.

—Henry Fogel, Fanfare, March 2022

The Art of Duo-Piano Playing [pdf]

There has never been a collection like this, curated and annotated with the usual care and authority by the Marston team...

A 47 page (English only) booklet with a wealth of photographs is the cherry on the top of this unexpected box of delights.

—Jeremy Nichols, Gramophone, August 2023

Luboschutz and Nemenoff: The Art of Duo-Piano Playing [pdf]

A 4-CD box set, well documented and with abundant imagery, from the Marston Records label 54010-2

Vronsky & Babin? No, Luboshutz and Nemenoff, like the other great piano duo that enchanted American musical life, in the order of Jews, Russians and exiles. A much thinner discographic heritage, is it due to the fact that they shared the same publisher, who recorded them both in such a rustic way? Ward Marston managed to give a certain breadth to these RCA sides that the pressings of war hardly spoiled...

Perfect edition. How do the Anglo-Saxons say? A labor of love.

—Jean-Charles Hoffelé, Artamag', 9 October 2022