| CD 1 (77:59) | ||

| HIS MASTER’S VOICE | ||

| 1. | MANON: Je suis encore tout étourdie (Massenet) | 3:47 |

| 6 October 1924; (cc5181-1) DB800 | ||

| 2. | MANON: Allons! Il le faut…Adieu, notre petite table (Massenet) | 3:57 |

| 6 October 1924; (cc5182-3) DB800 | ||

| 3. | MANON: Suis-je gentille...Obéissons quand leur voix appelle (Massenet) | 4:08 |

| 7 January 1925; (cc5550-2) first published on HMB-176 | ||

| 4. | THAÏS: Dis-moi que je suis belle [Scène du miroir] (Massenet) | 4:08 |

| 7 January 1925; (cc5552-1) DB810 | ||

| 5. | THAÏS: Te souvient-il du lumineux voyage (Massenet) | 4:14 |

| 7 January 1925; (cc5551-2) DB810 | ||

| VICTOR TALKING MACHINE COMPANY | ||

| 6. | FAUST: Jewel Song (Gounod) | 3:37 |

| 12 September 1927; (BVE-40006-1) Unpublished | ||

| 7. | THAÏS: Te souvient-il du lumineux voyage (Massenet) | 4:30 |

| 4 January 1926; (CVE-34255-1) 6578 | ||

| 8. | PAGLIACCI: Qual fiamma avea nel guardo...Che volo d’augelli (Leoncavallo) | 4:42 |

| 20 January 1926; (CVE-34161-9) 6578 | ||

| 9. | La danza (Rossini) | 3:11 |

| 26 March 1928; (CVE-42564-1) 6878 | ||

| 10. | Les filles de Cadiz (Delibes) | 3:46 |

| 26 March 1928; (CVE-42563-1) 6878 | ||

| 11. | Voci di primavera (J. Strauss) | 4:30 |

| 11 October 1927; (CVE-40297-3) Unpublished | ||

| 12. | The Second Minuet (Dawdon/Besley) | 2:45 |

| with Elmer Zoller, pianist; Raderman, violinist

23 September 1927; (BVE 43584-3) Unpublished |

||

| 13. | Little bit of a fellow (Norris) | 2:54 |

| with Elmer Zoller, pianist; Raderman, violinist

18 April 1928; (BVE-43583-3) Unpublished |

||

| 14. | The hand of you (Carrie Jacobs-Bond) | 2:37 |

| 7 March 1927; (BVE-38209-1) Unpublished | ||

| 15. | From the land of sky-blue water (Cadman) | 2:23 |

| with Clement Barone, flutist

4 January 1926; (BVE-34250-6) 1140 |

||

| 16. | Little grey home in the west (Löhr) | 3:02 |

| 4 January 1926; (BVE- 34249-7) 1140 | ||

| 17. | The old folks at home (Foster) | 3:35 |

| 12 September 1927; (BVE-40007-3) 1345 | ||

| 18. | Dixie (Emmett) | 2:30 |

| 26 March 1928; (BVE-42565-2) 1345 | ||

| THESAURUS TWENTY-FIVE SELECTIONS TAKEN FROM TRANSCRIPTION DISCS, 1936-1939 | ||

| 19. | EXULTATE JUBILATE: Alleluia (Mozart) | 2:55 |

| (MS 102438) 363 | ||

| 20. | Ave Maria (Bach-Gounod) | 3:03 |

| (MS 03544) 339 | ||

| 21. | The Holy Child (Easthope Martin) | 3:19 |

| (MS 03574) 604 | ||

| 22. | Eili Eili {Traditional: Yiddish} (arranged Schindler) | 4:13 |

| (MS 03542) 337 | ||

CD 1: | ||

| ||

| CD 2 (77:33) | ||

| 1. | HAMLETO: Principe Hamleto (Franco Faccio) | 3:43 |

| (MS 03539) 334 | ||

| 2. | LE COQ D’OR: Hymn to the Sun (Rimsky-Korsakov) | 3:26 |

| (MS 03540) 334 | ||

| 3. | LE NOZZE DI FIGARO: Deh, vieni, non tardar (Mozart) | 5:27 |

| (MS 03572) 430 | ||

| 4. | THAÏS: L’amour est une vertu rare (Massenet) | 3:49 |

| (MS 11552) 561 | ||

| 5. | L’ENFANT ET LES SORTILÈGES: Toi, le coeur de la rose (Ravel) | 2:02 |

| (MS 11551) 619 | ||

| 6. | Wohin? (Schubert) | 2:28 |

| (MS 03540) 334 | ||

| 7. | Die Lorelei (Liszt) | 7:17 |

| (MS 03574) 604 | ||

| 8. | Du bist wie eine Blume (Liszt) | 2:08 |

| (MS 03572) 430 | ||

| 9. | Wiegenlied, op. 41, no. 1 (Richard Strauss) | 4:25 |

| (MS 011634) 494 | ||

| 10. | Morgen, op. 27, no. 4 (Richard Strauss) | 3:05 |

| (MS 03865) 357 | ||

| 11. | Ständchen, op. 17, no. 2 (Richard Strauss) | 2:55 |

| (MS 11634) 494 | ||

| 12. | Si mes vers avaient des ailes (Hahn) | 2:06 |

| (MS 03543) 363 | ||

| 13. | Clair de lune (Szulc) | 3:12 |

| (MS 11634) 494 | ||

| 14. | Carmen Carmela (Hague-Ross) | 2:40 |

| (MS 03866) 414 | ||

| 15. | Ay, ay, ay {Traditional} (arranged Pérez-Freire) | 1:59 |

| (MS 03540) 334 | ||

| 16. | My lovely Celia (Monro) (arranged Wilson) | 2:50 |

| (MS 03865) 357 | ||

| 17. | Annie Laurie {Traditional Scottish} (Douglass-Scott) | 3:25 |

| (MS 03573) 355 | ||

| 18. | The Kerry Dance (Molloy) | 2:08 |

| (MS 03544) 339 | ||

| 19. | Last rose of summer (Moore) | 3:37 |

| (MS 03544) 339 | ||

| 20. | Danny Boy (Traditional: Irish) | 3:44 |

| (MS 03542) 337 | ||

| 21. | Still wie die Nacht (Böhm) | 3:12 |

| (MS 03866) 414 | ||

| 22. | Wien, Wien, nur du allein (Sieczynski) | 2:30 |

| (MS 03539) 334 | ||

| 23. | Rain (Eugene Ford) | 2:32 |

| (MS 11554) 552 | ||

| 24. | My old Kentucky home (Foster) | 2:44 |

| (MS 03572) 430 | ||

| ||

CD 2: | ||

Producer: Michael B. Dougan

Production Coordinator: Jeffrey J. Miller

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston

Photographs: Girvice Archer, Lawrence F. Holdridge, and Charles Mintzer

Audio Sources: Lawrence F. Holdridge: CD 1, Track 6 and Michael Quinn: CD 1, Tracks 19-22; CD 2, Tracks 1-24

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank Ramona Fassio

Marston would also like to the Tom W. Dillard of The Arkansas Studies Institute and the Arkansas Arts Council for their support of this CD release

For a complete biography: Mary Lewis—The Golden Haired Beauty With The Golden Voice was published in June 2001. The book may be ordered from Rose Publishing Co., Inc., Little Rock, AR. This program is supported in part by the Arkansas Arts Council, an agency of the Department of Arkansas Heritage, and the National Endowment for the Arts.

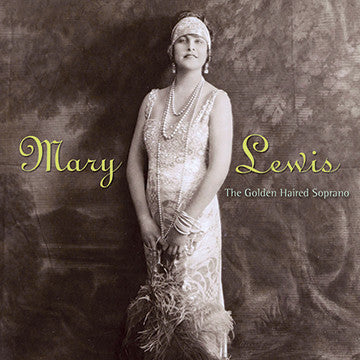

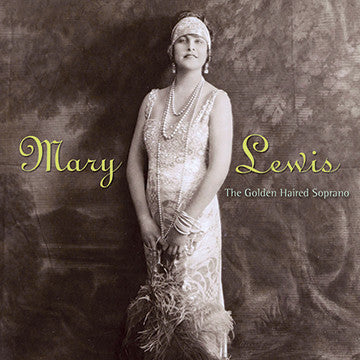

MARY LEWIS

The Golden Haired Beauty With The Golden Voice

Although she was described as one of the most publicized singers of the 1920s, her story has almost been forgotten. Who was Mary Lewis?

Mary began life at the turn of the 20th century in the slums of the South. Although christened Mary Kidd, her mother remarried after the death of Mary’s father and Mary then became Mary Maynard. In 1915 she married J. Keene Lewis, remaining through two subsequent husbands Mary Lewis. Her extraordinary story really began with her rescue from poverty by a Methodist pastor and his wife, who not only raised her, but also schooled her and grounded her in music. The Reverend William and Anna Fitch were both college graduates and had a wide and varied experience in their ministry. William and Anna were in their 60s when they took Mary, aged seven, into their home.

In the Fitch home, Mary began the transformation from a mangy wretch to an internationally renowned beauty. She was also continually in trouble. The strict confines of a pastor’s home warred with a girl straining to become a part of the “ragtime” era along with her peers.

Mary’s singing inspired Little Rock civic leader Henry F. Auten to bring the girl into his home and arrange for voice lessons. She attended Little Rock High School for three years, her only formal education.

Mary’s 1915 marriage was short-lived. Hoping that her voice was to be her ticket to fame, she left Little Rock with a traveling stage troupe, ending up in California. There she became many things. She sang in a restaurant and in vaudeville. After too much singing caused her to lose her voice, she became a Christie comedy beauty in Hollywood in the silent movies. After her vocal difficulties healed, Mary Lewis invaded New York City in 1920 to become a prima donna first in the Greenwich Village Follies and then in the Ziegfeld Follies of 1921 and 1922.

Using the salary earned at the Follies, Mary Lewis began serious vocal study with William Thorner to pursue her goal of appearing in opera. Encouraged after an audition with Giulio Gatti-Casazza at the Metropolitan Opera Company she followed his recommendation to study in Europe. She made her operatic debut at the Volksoper in Vienna in 1923, singing the role of Marguerite in Gounod’s Faust opposite Viorica Ursuleac, Trajan Gosavescu, and Emmanuel List; the conductor was Felix Weingartner. Soon after her Vienna debut, Mary met and had the opportunity to sing for Franz Lehar, the Hungarian operetta composer. In spite of his attractive offers, Mary refused to give up her dream of opera for operetta.

Mary Lewis was contracted for three appearances with the British National Opera Company in the summer of 1924. She was scheduled to sing Musetta in La bohème and two roles in Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffman. At the last moment she was called to substitute in the role of Antonia for Maggie Teyte who had lost her voice. Mary had never sung the role and later said, “It never occurred to me there was anything heroic or remarkable in my singing the role on such short notice and I went on that night quite as a matter of course.” The usually reserved English audience called her back with thunderous applause for 15 curtain calls.

The B.N.O.C. responded with a contract revision awarding Mary 13 appearances instead of her previously scheduled three. Mary appeared as Mary in the world premiere of Ralph Vaughn Williams’s English folk opera, Hugh the Drover; Tudor Davies, the noted Welsh tenor, was cast as Hugh.

Mary Lewis returned to Paris where she again encountered Lehar, who requested her to play the lead in one of his operettas. Mary again declined. Later, at Monte Carlo, Mary was informed the director of the Casino de Paris had scheduled a French revival of Lehar’s The Merry Widow and Lehar had declared that unless Mary Lewis was engaged for the lead role, the operetta would not go on. Mary relented and signed a contract for 150,000 francs for ten weeks, one of the largest salaries paid for musical comedy in Paris. Mary Lewis sang the lead role in French at the rebuilt Apollo Theatre.

After more appearances in Europe, she returned to New York. Following an audition, the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera Company, Gatti-Casazza, awarded her a contract for the 1926-1927 season at a time when American singers were finding difficulty wedging in between the established European artists. By way of warm up, on 1 November 1925, she made the first of many radio broadcasts on station WEAF, singing with the Harlem Philharmonic. Then she was heard on 22 November as guest soloist with the State Symphony Orchestra in an Atwater Kent Radio Hour broadcast with Ernst von Dohnanyi conducting.

Hundreds stood in line for hours to purchase tickets on 28 January 1926 to hear Mary’s debut at the Metropolitan Opera Company. Cast as Mimi in La bohème, Mary displayed a charisma and vibrancy that enchanted the crowd if not all the critics.

At the end of the 1927 season at the Met, Mary Lewis married the multi-talented leading German opera singer, Michael Bohnen, also under contract with the company as a leading bass/baritone from 1923 to 1932. Calling himself a “singing actor,” Bohnen produced and acted in 30 films and made the transition from silent films to success in talking films. He was large in size with a personality to match. Temperamentally explosive and egotistical, creative and non-traditional, he used his great physical strength in performances and off-stage antics.

For Mary Lewis the marriage was disastrous. She gained weight and was accused of alcoholism. Following a clash of similar artistic temperaments, the marriage ended with divorce in Hollywood in 1930. After working hard to reduce her weight, Mary was offered a film contract with Pathé. Although the agreement was the first to be recorded verbally via the new talkie medium itself, the film was never made.

The Depression Years found Mary, like others, unemployed. As usual, she did the unusual; she married an oil-shipping millionaire, Robert Hague, in September of 1931. Although it appeared she had abandoned her professional career, Mary Lewis continued to use her musical talents performing in and promoting many benefit concerts. The Hagues lived in a penthouse apartment at the top of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel.

Mary was compared to Cinderella. Unlike Cinderella, she didn’t live happily ever after–but that was a fairy tale–the Mary Lewis story is true. She has been described as an “enigma”–something of a puzzle, a riddle. There is a very high probability that her persistent health problems and early death were directly linked to radiation poisoning she contracted in 1922 when she sang “Weaving” in a darkened theater illuminated only from the glow of her radium-painted “Lace Land” dress.

Although she never quite knew who she was, she made a name for herself as Mary Lewis–the golden haired beauty with the golden voice. Mary Lewis was born 29 January 1897, in Hot Springs, Arkansas. She died 31 December 1941, in New York City, New York. Her final resting place is in Pinecrest Memorial Park, Alexander, Arkansas.

© Alice Fitch Zeman, 2005

The Records of Mary Lewis

“Her singing fell rather short of the standard set by her acting” intoned the music critic of the London Times, writing of Mary Lewis’s first performance as Mimi in La bohème in 1924. Two years later in her New York operatic debut Olin Downes thought her contribution as Mimi was “histrionic rather than vocal,” while the venerable W. J. Henderson (whose The Art of the Singer had been published in 1911) found her at best only “creditable.” Samuel Chotzinoff alone saw possibilities in this early crossover star. Lewis’s tones were “firm and rounded, with no trace of a tremolo, the lower register is little weak and the middle not very much stronger. But the upper register is brilliant, and, when Miss Lewis chooses to make it so, it is sensuous.”

Although not conservatory-trained and always subjected to technical defects, Mary Lewis worked on her voice up to the time of her death. The result is that one hears her voice in three stages that coincide roughly with the three phases of her recording career.

Lewis’s first records were recorded acoustically for His Master’s Voice in England in 1924 and early 1925. The first sessions consisted of extended excerpts of Vaughn Williams’s Hugh the Drover. In keeping with other acoustic sets by the company at that time, the engineers attempted to catch ambiance at the expense of presence. Nevertheless, the purity of her voice in its upper register is much in evidence, and she is not overpowered by the sturdy Wagnerian tenor, Tudor Davies. Her other acoustics were studio recordings of arias from Manon and Thaïs. Lewis here compares well against most French sopranos, the bonus being that there is power without acidity. Much of Lewis’s truncated professional career was spent in France, and here as well as later the French text is well projected.

The second round of recording took place in America in 1926. “Te souvient-il du lumineux voyage”–the so-called Mediation–from Thaïs was re-recorded. The electrical method captured her lower voice better than the acoustic a year earlier, but more importantly Lewis’s registers were much more equalized. The brilliant upper register capped her performance of this aria, and this recording, paired with the Pagliacci aria, “Qual fiamma avea nel guardo…Che volo d’augeli,” long remained in the catalogue; it was Lewis’s signature record, comparable to Paderewski’s recording of the slow movement of the “Moonlight Sonata” or Jose Iturbi’s Chopin “Polonaise.”

Victor did turn her loose on the Jewel Song from Faust. She sang Marguerite at the Metropolitan Opera House opposite Chaliapin’s last performances as the Devil, but the disk was not published. Otherwise, Victor used her in songs. There is not a bad or boring record in the lot. She made the classic recording of “Dixie;” and there is more than sufficient excitement as well as vocal accuracy in “Les filles de Cadiz” and “Voices of Spring.” A personal favorite is the otherwise unknown and previously unpublished “The Second Minuet.” Never did she sound like an opera singer attempting songs: each word and phrase received its proper attention and even trivial material was accorded respect, making her a sort of female John McCormack. The voices of individual characters–as in “The Second Minuet”–are individualized vocally but with no loss of the vocal line.

During the 1930s Lewis began repairing her career. A 1934 Town Hall concert featured songs by Satie, Duparc, Debussy, Saint-Sa91ns, Brahms, Wolf, and Strauss; not a program for the masses. Critic F. D. Perkins called it a re-debut, and “not of the type chosen by an opera singer making a temporary excursion into the concert field.” It was proof her career “has entered auspiciously a new phase that could lead to artistic attainments beyond those of her Metropolitan days.” Evidence of her new stature appeared in the third set of recordings, those for the NBC Thesaurus series.

Recorded in February 1937 with a small salon orchestra drawn from principals of the New York Philharmonic -Symphony, the series featured some arias but also songs. Vocally, she displays a strong lower register. Her top notes, which critics had frequently called shrill, had not changed, but the power and depth of the voice gives new force to her interpretive powers. The repertory, especially in the popular American songs, was hackneyed, but the interpretations were not; these were not just tossed off old chestnuts.

Alongside the French chansons and German Lieder there stands a piece utterly out of character for an American singer from Arkansas and yet one that in its text and its her performance underlines all the tragedy that underlay the glamour of her truncated career and life:

“Eili, Eili, lomo asvtonu?”

“My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?”

Mit Feire un Flamm hot men uns gebrennt,

With fire and flame they have burnt us.

Iberall hot mens uns gemacht zu Schand, zu Spott.

Everywhere they have shamed and derided us.

Obzutreten fun uns hot doch keiner mit gewagt.

Yet none among us has dared to depart

Fun unser heilieger Toire, fun unser Gebot.

From our Holy Scriptures, from our Law.

“Eili...”

“Eili...

Tog un Nactt nor ich tracht un ich bet,

By day and night I only yarn and pray

Ich huet mit Moire unsre Toire, un ich bet:

I anxiously keep our Holy Scriptures and I pray

Rette uns, rette uns amol.

Save us, save us once again.

For unsre Ovos, Ovos avosseinu

For the sake of our fathers and father’s fathers,

Hoer zu mein Gebet un mein Gewein,

Listen to my prayer and to my lamenting

Weil heifen kenst du, nor Gott allein.

For only you can help, You, God alone.

Weil: “Sh’ma Yisroel, Adonai Elohenu, Adonai Echod!”

For it is said, “Hear, O Israel, the Lord is our God, The Lord is One.

It is time to elevate Mary Lewis to the ranks of important American singers.