| CD 1 (79:10) | ||

| 1. | Murmelndes Lüftchen (Jensen) | 3:58 |

| July 1913; (1419) 83021 | ||

| 2. | Sehnsucht (Rubinstein) | 4:45 |

| July 1913; (1420) 83020 | ||

| 3. | LOHENGRIN: Mein lieber Schwan (Wagner) | 5:15 |

| July 1913; (1422) 83017 | ||

| 4. | LOHENGRIN: Mein lieber Schwan (Wagner) | 4:49 |

| February 1914; (2891) 83017 | ||

| 5. | DER FREISCHÜTZ: Durch die Wälder (Weber) | 4:00 |

| 18 February 1915; (3589) 83028 | ||

| 6. | Sehnsucht (Rubinstein) | 3:59 |

| 18 February 1915; (3590) 73005 | ||

| 7. | RIENZI: Allmächt'ger Vater (Wagner) | 4:38 |

| 23 February 1915; (3596) 82269 | ||

| 8. | DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE: Dies Bildnis (Mozart) | 3:41 |

| 13 February 1915; (3597) 82260 | ||

| 9. | LA JUIVE: Rachel quand du Seigneur (Halévy) | 4:40 |

| 23 February 1915; (3598) 82260 | ||

| 10. | LOHENGRIN: Mein lieber Schwan (Wagner) | 4:43 |

| 24 February 1915; (3602) 83017 | ||

| 11. | L'AFRICAINE: O paradis, sorti de l'onde (Meyerbeer) | 3:35 |

| 24 February 1915; (3603) 83033 | ||

| 12. | Das Zauberlied (Meyer-Helmund) | 4:44 |

| 26 February 1915; (3610) 82280 | ||

| 13. | DIE WALKÜRE: Winterstürme wichen (Wagner) | 3:09 |

| 1 March 1915; (3615) 82246 | ||

| 14. | FIDELIO: Gott, welch Dunkel (Beethoven) | 4:47 |

| 1 March 1915; (3616) 83030 | ||

| 15. | LOHENGRIN: Gralserzählung (Wagner) | 4:46 |

| 3 March 1915; (3621) 82277 | ||

| 16. | DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG: Am stillen Herd (Wagner) | 4:42 |

| 1 April 1915; (3680) Unpublished | ||

| 17. | DIE MEISTERSINGER VON NÜRNBERG: Preislied (Wagner) | 4:32 |

| 3 March 1915; (3622) 82276 | ||

| 18. | Murmelndes Lüftchen (Jensen) | 4:13 |

| 3 March 1915; (3623) 83037 | ||

| CD 2 (71:36) | ||

| 1. | SIEGRFRIED: Schmiedelied (Wagner) | 3:35 |

| 1 April 1915; (3681) 83040 | ||

| 2. | JOSEPH: Champs paternels (Méhul) | 4:38 |

| 30 March 1916; (4617) | ||

| 3. | O schöne Zeit (Götze) | 3:38 |

| 31 March 1916; (4623) 73008 | ||

| 4. | Still wie die Nacht (Böhm) | 3:29 |

| 18 April 1916; (4664/BA28254) 13179 | ||

| 5. | Die Allmacht (Schubert) | 4:16 |

| 18 April 1916; (4665) 82252 | ||

| 6. | LA MUETTE DE PORTICI: Du pauvre seul (Auber) | 4:28 |

| 18 April 1916; (4666) | ||

| 7. | Weiss ich dich in meiner Nähe (Abt) | 3:26 |

| with Marie Rappold, soprano | ||

| 24 April 1916; (4682/BA28251) 13191 | ||

| 8. | LOHENGRIN: Das süsse Lied verhallt (Wagner) | 3:49 |

| with Marie Rappold, soprano | ||

| 24 April 1916; (4683) 83054 | ||

| 9. | Wenn die Schwalben heimwärts zieh'n (Abt) | 3:43 |

| with Marie Rappold, soprano | ||

| 25 April 1916; (4687/BA28254) 13157 | ||

| 10. | DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE: Wie stark ist nicht dein Zauberton (Mozart) | 3:24 |

| 9 February 1917; (5356) 57017 | ||

| 11. | Panis angelicus (C. Franck) | 4:08 |

| 21 February 1917; (5392) 83083 | ||

| 12. | DIE WALKÜRE: Ein Schwert verhiess mir (Wagner) | 4:26 |

| 2 March 1917; (5425) 82246 | ||

| 13. | STABAT MATER: Cujus animam (Rossini) | 4:12 |

| 7 March 1917; (5434) 83082 | ||

| 14. | RIENZI: Erstehe, hohe Roma, neu (Wagner) | 3:31 |

| 2 April 1917; (5485) 82275 | ||

| 15. | MARTHA: Ach so fromm (Flotow) | 3:24 |

| 9 April 1917; (5496) 82278 | ||

| 16. | DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER: Willst jenes Tages (Wagner) | 3:15 |

| 30 April 1917; (5528) 57017 | ||

| 17. | TANNHÄUSER: Gepriesen sei (Wagner) | 3:09 |

| with Marie Rappold, soprano | ||

| 1 May 1917; (5529) 82279 | ||

| 18. | DIE WALKÜRE: Siegmund heiss ich (Wagner) | 3:25 |

| with Marie Rappold, soprano | ||

| 2 May 1917; (5533) 82277 | ||

| 19. | Traum durch die Dämmerung (Strauss) | 3:31 |

| 3 May 1917; (5535) 82252 | ||

CD 1: | ||

CD 2: | ||

Producers: Scott Kessler & Ward Marston

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston

Photographs: Girvice Archer, Rudi Van den Bulck, the Edison National Historic Site, Charles Mintzer, the National Park Service, the Stuart-Liff Collection, the United States Department of the Interior, and Pierre Van de Weghe

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank Gregor Benko, Rudi Van den Bulck, Jerry Fabris, Lawrence F. Holdridge, Peter Lack, Roger Gross Ltd., and Raymond Wile for their help in the production of this CD release.

Marston would also like to thank the Edison National Historic Site, the National Park Service, and the United States Department of the Interior for conserving and sharing rare recorded treasures.

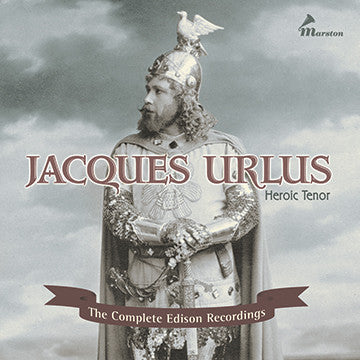

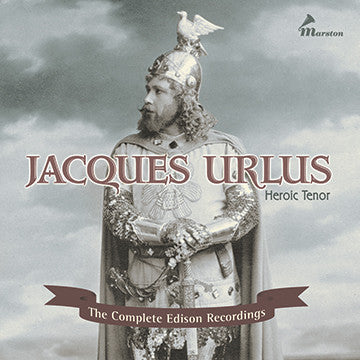

Jacques Urlus (1867-1935)

Recent history would have it that the term Heldentenor virtually began (and ended) with the great Danish giant, Lauritz Melchior. But at Covent Garden, in 1924, an inexperienced young Melchior shared roles with the veteran, Jacques Urlus. In a sense, at that moment in time, the torch was passed. If one looks at the casts of Wagner’s operas during the early years of the Metropolitan Opera, in the period prior to the cancellation of German opera because of World War I, the name of Jacques Urlus appears with astonishing regularity. From the time of his debut as Tristan on 8 February 1913 to his last performances early in 1917, Urlus regularly appeared two or three times a week, singing Tristan, Siegmund, both the elder and younger Siegfried, Walther, Parsifal, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, as well as Tamino in Die Zauberflöte, and Florestan in Fidelio. Since the departure of Jean de Reszke in 1901, the Met had struggled without notable success to find a suitable replacement for the legendary Polish tenor. Jacques Urlus clearly was the answer. His distinguished bearing, beautiful voluminous voice, sensitive musicianship, and extraordinary stamina all contributed to making Urlus the ideal Wagnerian tenor.

Richard Wagner was said to have consistently urged his interpreters to sing in the Italian manner. When he was planning the first Bayreuth festival in 1876, he wrote to the renowned Manuel Garcia, Jr., asking him to undertake the training of the singers. Garcia had previously taught Wagner’s niece, Johanna (the original Elizabeth in Tannhäuser), as well as such luminaries as Jenny Lind. While Garcia declined, the claim that Wagner wished his music to be sung in a smooth, unforced bel canto manner is supported by his admiration for the Garcia school, whose antecedents date back to the eighteenth century. No other Heldentenor on record answers this ideal as fully as Jacques Urlus. His well-focused, powerful voice was produced in a seemingly effortless manner. A scrupulous musician, he sang with care and used a wide range of dynamics for expressive purpose. His recordings are characterized by the direct, authoritative manner of a master.

Urlus was born on 9 January 1867 in Herkenrath, now part of Belgium, to Dutch parents. They moved back to Holland when Jacques was one year old, settling in his mother’s home-town of Tilburg. It was here Urlus spent his childhood, singing in the church choir and playing the cornet. He left school at twelve and was apprenticed to a blacksmith. At fifteen he went to work with his father in a steel mill in Utrecht. While in Utrecht he sang in church choirs and occasionally appeared as a soloist. After military service, during which lack of funds denied him the opportunity to attend the Brussels Conservatory, Urlus returned to Utrecht and continued as a church soloist. It was not until he was twenty-three that Urlus was actually paid for singing. At twenty-six he married Hendrika Johanna Jacobs, and through the years they had five children, four sons and a daughter. Shortly afterwards he signed a contract with the Nederlandsche Opera, which included a clause that he should have some professional coaching in singing and acting. Therefore, at the age of twenty-seven, Urlus first studied briefly with Hugo Nolthenius in Utrecht. After moving to Amsterdam, he worked for a time with Anton Averkamp before completing his studies with the noted contralto, Cornelie van Zanten who was also the teacher of Julia Culp and Wagnerian tenor Henk Noort.

Urlus’s debut as Beppe in I Pagliacci took place on 23 October 1894. But Urlus was soon given the opportunity to show his true potential as the lead in Méhul’s Joseph, and Max in Der Freischütz. The Nederlandsche Opera was based in Amsterdam but toured throughout The Netherlands. During his second season Urlus assumed the roles of Siegmund, Tannhäuser, Faust, Don José and Radamès. While his later American career focused almost exclusively on Wagner, in Europe Urlus’s repertoire was very diversified. His roles included Canio, Manrico, Otello, Cavaradossi, Pinkerton, Turiddu, and Faust. Urlus remained in Amsterdam for five years, turning down contract offers from Antwerp and Frankfurt.

In 1900, Urlus became the principal tenor of the Leipzig Opera. Here he sang the major Wagnerian roles, including his first Tristan and both Siegfried roles. His other roles included Samson and Raoul in Les Huguenots. He performed in Leipzig for almost 20 years, retaining the freedom to give guest appearances throughout the world. During his early years there, Gustav Mahler attempted unsuccessfully to lure him to Vienna, and the Berlin Royal Opera sought him out, but Urlus was content to remain in Leipzig, using these offers to obtain a higher salary.

Urlus achieved great success in London in 1910, and sang Siegmund at Bayreuth in 1911 and 1912. His international reputation began to spread and he first traveled to the United States in 1912, appearing with the Boston Opera. His debut was as Tristan on 12 February; Johanna Gadski was his Isolde, and Felix Weingartner conducted. The reviews were ecstatic. The critic, Philip Hale, who was known for his caustic comments wrote, “His declamation always had force and meaning, and he did not shout or bawl...In cantabile passages, voice, vocal skill and emotional expression gave an additional glory to [the] music... All in all, no German tenor who has taken the part of Tristan in this city has equaled him.” Another review stated, “Urlus...sang the music of Tristan as it has not been sung since Jean de Reszke, indeed with a heroic splendor never attained by him.” In 1914, the Boston Opera joined with Covent Garden to give all-star performances in Paris. Urlus sang Tristan to Margaret Matzenauer’s Isolde, under the baton of Artur Nikisch.

His success in Boston led to a contract with the Metropolitan Opera. Urlus joined the company late in the 1912-13 season, making his debut as Tristan on 8 February 1913. Unfortunately, he was impeded by a bad cold and could barely speak his lines. But the following week, fully recovered, he had great success in Siegfried. Pitts Sanborn in the New York Globe wrote, “The voice that Mr. Urlus revealed yesterday is of ingratiating quality and he really sings, sings with a degree of skill and variety of nuance rarely heard from a tenor in the later music dramas of Wagner.” Besides an occasional Tamino or Florestan, Urlus appeared solely in Wagnerian roles. A glance at the Metropolitan Opera Annals reveals his extraordinary stamina: a Lohengrin, two days later Siegmund, five days later the younger Siegfried, four days later Siegfried again! And this pace was repeated throughout his American career.

Urlus first appeared as a concert artist in New York on 20 November 1913, singing with the New York Philharmonic under Josef Stransky. A review in the Musical Leader spoke of “the wonderful beauty of his voice, clear, pure and ringing, with no harsh quality at any moment. His “Prayer” from Rienzi was as fine an example of pure singing as the concert stage has offered in a long time.”

When the Met discontinued performances of German opera in 1917, Urlus returned to Leipzig as well as concertizing in Scandinavia. He continued to perform regularly in The Netherlands, Germany, and Scandinavia. In 1921 he first returned to London for a concert and as noted previously, shared roles with Melchior in 1924. Urlus performed in New York once more in 1923 with a remarkable German company that included Eva von der Osten, Meta Seinemeyer, Friedrich Schorr, Heinrich Knote, and Alexander Kipnis. In 1925 he performed at the famous Zoppoter Waldoper, and appeared in 24 performances with the Berlin Opera as late as 1927, when he was 60 years old. He sang Tristan at the Paris Opera in 1930 and performed on stage in The Netherlands until 1931. Afterwards, he continued concertizing until his final illness. He was renowned for his insightful interpretation of Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde” which he sang at the Salzburg Festival in 1928. He was also greatly admired as the Evangelist in Bach’s “Mattheuspassion” which was always under the baton of Willem Mengelberg. In 1929 he wrote his autobiography Mijn Loopbaan (My Career) and his last operatic appearance was on 19 January 1933 as Tristan in Heiligersberg. Urlus died unexpectedly following surgery for prostate cancer on 6 June 1935 at the age of 68.

Jacques Urlus made almost 150 recordings, beginning with 25 cylinders sung in Dutch for Pathé in 1903, and ending with two electrics for Odeon in 1927. These CDs are devoted to the Edisons, which reproduce Urlus’s voice during his triumphant Metropolitan seasons, from 1913-1917. While these do contain a number of recordings from Wagner, there is a surprising amount of diversity considering how exclusively Urlus was used at the Met. He recorded arias and duets from Der Freischütz, La Juive, L’Africaine, Joseph, La Muette de Portici, and Martha, as well as Fidelio and Die Zauberflöte which he did sing at the Met. There are also excerpts from Rossini’s Stabat Mater as well as Franck’s “Panis angelicus,” and a number of songs. Urlus’s depth and range as an artist is therefore quite fully revealed in these recordings. The Edisons, with their superb sound, give a very clear picture of this remarkable artist in his prime.

Among the finest Wagnerian recordings are two excerpts from Rienzi. We can immediately hear Urlus’s firm, ringing sound which is always absolutely steady and controlled. The voice is like a smooth sheet of precious metal, glowing and resonant. There is never any sign of weakness in the middle or lower registers, as with many tenors. Urlus is careful in the upper register, never forcing or exaggerating climaxes. While this might not give his singing the visceral thrill of his contemporary, Enrico Caruso, the beauty of his big, compact sound more than compensates for that missing sense of danger. In the lyrical “Allmächt’ger Vater,” his superb legato elegantly carries the melodic line forward. Each phrase is carefully weighed, held in balance. His voice is placed high and forward; for all the fullness at bottom, the sound is tenorial. It is a metallic sound, but burnished—no rough edges. In the second Rienzi excerpt, “Erstehe, hohe Roma, neu!”, Urlus displays plenty of power in the declamatory phrases, producing a steady flow of smooth, vibrant tone.

Urlus was a famous Lohengrin and his recordings from that opera are superb. One is constantly struck by the singer’s control and the exquisite sound emitted. His approach to the music is more human than spiritual. His Lohengrin, while noble in manner, is approachable and reacts to Elsa with warmth and tenderness. In the duet, “Das süsse Lied verhallt” with the fine American soprano, Marie Rappold, the emotional intensity between the singers is evident. The great narrative, “In fernem Land” is not treated by Urlus as a grand climax, but instead has a tragic overtone... again displaying the tenor’s sense of the human drama that has unfolded. Siegfried’s “Schmiedelied” is truly sung, not huffed and puffed until exhaustion sets in. Urlus sings with an acutely measured rhythmic sense and his voice never shows sign of strain.

When not singing Wagner at the Met, Urlus was usually heard as Tamino. The two arias from Die Zauberflöte are beautifully paced performances. The tenor’s monumental sound and sensitive musicianship seem perfect for Mozart. The famous aria, “O paradis,” from Meyerbeer’s L’Africaine, is sung magnificently by Urlus. His tempo is slow, and the long, drawn out phrases and heady top notes are reminiscent of what we hear of Jean de Reszke on the Mapleson cylinders. When his voice rises, Urlus has a way of softening the strike of the vocal chords so that no strain is revealed. A beautifully sung excerpt from Auber’s La Muette de Portici suggests that Urlus truly represents a singing style that derives from the nineteenth century.

Urlus’s strengths as an oratorio singer are revealed by a hypnotic performance of César Franck’s elegiac “Panis angelicus” and a carefully paced, but stirring “Cujus animam” from Rossini’s Stabat Mater. He was also a superb Lieder singer, capable of surprising delicacy—sensitive to every nuance. Erik Meyer-Helmund’s romantic “Das Zauberlied” is gently caressed by Urlus. In contrast, Schubert’s marvelous song, “Die Allmacht” is sung passionately. At times, his dramatic ringing tones propel this mini-drama forward with surprising urgency.

He seemed to go on forever. A 1933 Concertgebouw concert with Urlus (at the age of 66) under Erich Kleiber was reviewed in De Telegraaf. “One heard him as always, in astonishment, astonishment at the still so enchanting, radiant young voice, because of the splendid manner of singing, the ideal timbre, the enormous, mighty, volume, in short in the class of his own that is Urlus. One gives him jubilant ovations in the warmth, the surprise we always experience anew as he, recharged, with fresh energy, sound power, capacity in technique and beauty of his art, gratifying in limpid capacity—before us stands—the hero!”

©Harold Bruder, 2001

Jacques Urlus was already a veteran of the recording studio by the summer of 1913 when he cut his first disc recordings for the Edison Company. In fact, he had previously made over seventy-five sides for Pathé and the Gramaphone Company between 1903 and 1912. Although many of these discs are eagerly sought by collectors, his Edison discs, presented here in their entirety, are unquestionably his greatest. This is due in no small measure to the fact that Urlus’s voice was so magnificently captured by Edison’s recording method.

Thomas Edison began experimenting with disc recording early in the year 1910, and even at the age of sixty-five, he approached the project with tremendous enthusiasm and vigor. He took a personal interest in all aspects of disc recording, manufacture, and reproduction. He also decided to take an active part in the auditioning of musicians to be recorded. This was unfortunate since Edison possessed at best a rudimentary knowledge of music and no talent for making such decisions. He was, by this point, almost completely deaf and one can only speculate as to what opera singing must have sounded like to his ears. Nevertheless, his opinionated and often negative comments on well-known singers have often been quoted and could well be the subject of a most amusing essay.

Jacques Urlus recorded ten sides during his first session for Edison in his London studio in July 1913. Once the wax masters had been received in New York for processing, six titles were chosen for publication and assigned catalogue numbers. They were immediately withdrawn, however, probably because they had been incorrectly recorded at 75 rpm instead of the 80 rpm speed upon which Edison insisted. Only two of these titles have ever surfaced as commercial pressings. A third disc from this group exists in test pressing form at the Edison National Site. (CD1, Tracks 1-3)

The following February saw Urlus in London again, re-recording most of the previously rejected titles. This session only yielded one satisfactory item—“Mein lieber Schwan” from Lohengrin which replaced the 1913 recording. This version, (CD 1, Track 4) was also quickly withdrawn for reasons unknown. With the outbreak of World War I, Edison shut down all recording operations in Europe and thereafter, recording was confined to his New York studio. During Urlus’s first New York session, he once again recorded many of the same titles and this time, all were published. For the next two years, Jacques Urlus recorded some forty titles for Edison, many of which remained in the catalogue until the company went out of business in 1929. Thomas Edison was particularly delighted with Urlus, whose name he quite consistently misspelled Urlis. I quote here two of Edison’s handwritten evaluations.

L’Africaine “O paradis”: “Splendid—no tremolo. Caruso cannot possibly best this. Urlis in fine voice—talk to him about it.”

Siegfried “Schmiedelied”: “The whole record is good. The music is especially good - dramatic. If we could get the same dramatic effect on other opera pieces, it would be good.”

Jacques Urlus wrote to Edison on 5 April 1915 thanking him for sending samples of some of his newly recorded records along with a machine. Over top of Urlus’s letter, Edison penned the following comments intended for his reply.

“We all notice that when the tunes you sing are composed of long sustained notes and are not broken up by a number of german (sic) words, they are very beautiful. Too much talking in german (sic) is fatal to the musical quality – the chords cannot talk and sing simultaneously without bad results. I hope the next time you will let us have some songs like the Eve Star from Tannhauser which are suitable for tenor.”

Aside from musical matters, Edison insisted upon the highest standards of technical excellence in record production. In 1923, for example, one Edison dealer wrote that a customer had complained that Urlus’s record of “Siegmund heiss ich” blasted on loud notes. Edison immediately had the record evaluated by several assistants. It was indeed found defective and quickly placed on the cut out list.

I have presented here all of Urlus’s Edison recordings in chronological matrix number order except for the two arias from Die Meistersinger which I have placed together for the sake of musical continuity. In cases where two takes were available, I invariably opted for the one with superior sound since Urlus was interpretively consistent from take to take. Transferring these discs presented few obstacles and as I worked, I was completely free to revel in Urlus’s artistry. It is my hope that this issue will help to establish him solidly in the pantheon of great “Helden tenors”.