| CD 1: (78:12) | ||

PIANO | ||

SERGEI TANEYEV† (1856–1915) | ||

| 1. | Mozart: Fantasie in C Minor, K. 396 | 2:44 |

| 1891; (C143) Russia | ||

JOSEF HOFMANN (1876–1957) | ||

| 2. | Anton Rubinstein: Contredanse A, no. 3 from Le Bal, op. 14* | 1:22 |

| 24 December 1895 o.s.; (C139) Moscow | ||

| 3. | Anton Rubinstein: Contredanse B, no. 3 from Le Bal, op. 14* | 1:28 |

| 24 December 1895 o.s.; (C139) Moscow | ||

| 4. | Wagner-Brassin: Magic Fire Music from Die Walküre | 3:17 |

| 10 February 1896 o.s.; (C140) Moscow | ||

| 5. | Mendelssohn: Song Without Words, op. 38, no. 5, “Passion”* | 2:15 |

| Date unknown o.s.; (C137) Russia | ||

ANNA ESSIPOVA§ (1851–1914) | ||

| 6. | Godard: Gavotte in G, op. 81, no. 2 | 2:19 |

| 15 November 1898 o.s.; (C136) Apartment of Julius Block, Russia | ||

PAUL PABST† (1854–1897) | ||

| 7. | Chopin: Nocturne in E, op. 62, no. 2 | 3:46 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C121) Moscow | ||

| 8. | Chopin-Pabst: Waltz in D-flat, op. 64, no. 1, “Minute” | 1:48 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C122) Moscow | ||

| 9. | Schumann: Carnaval, op. 9: “Chopin” | 1:01 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C122) Moscow | ||

| 10. | Schumann: Carnaval, op. 9: “Estrella” | 0:34 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C122) Moscow | ||

| 11. | Tchaikovsky-Pabst: Paraphrase on Sleeping Beauty, op. 66 | 3:23 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C124) Moscow | ||

| 12. | Pabst: Papillons | 2:13 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C125) Moscow | ||

| 13. | Chopin-Pabst: Mazurka in D, op. 33, no. 2 | 1:34 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C125) Moscow | ||

| 14. | Chopin-Pabst: Mazurka in D, op. 33, no. 2 | 2:59 |

| 12 February 1895 o.s.; (C123)1 Moscow | ||

ANTON ARENSKY† (1861–1906) | ||

| 15. | Arensky: Improvisation in E-flat | 2:54 |

| 24 November 1892 o.s.; (C112) Russia | ||

| 16. | Arensky: Improvisation in A | 2:31 |

| 24 November 1893 o.s.; (C120) Russia | ||

| 17. | Arensky: Nocturne in D-flat, no. 3 from 24 Morceaux Charactéristiques, op. 36 | 2:33 |

| 25 November 1894 o.s.; (C114) Moscow | ||

| 18. | Arensky: Intermezzo in F Minor, no. 12 from 24 Morceaux Charactéristiques, op. 36 | 0:53 |

| 25 November 1894 o.s.; (C114) Moscow | ||

| 19. | Arensky: Consolation in D, no. 5 from 24 Morceaux Charactéristiques, op. 36 | 2:17 |

| Date not specified; (C115) Russia | ||

| 20. | Arensky: Le ruisseau dans la forêt in G, no. 15 from 24 Morceaux Charactéristiques, op. 36 | 3:03 |

| 20 December 1894 o.s.; (C109) Moscow | ||

| 21. | Arensky: Ioniques, no. 3 from Essais sur les Rythmes Oubliés, op. 28 | 1:36 |

| 20 December 1894 o.s.; (C119) Moscow | ||

| 22. | Arensky: Strophe Alcéene, no. 5 from Essais sur les Rythmes Oubliés, op. 28 | 1:37 |

| 20 December 1894 o.s.; (C119) Moscow | ||

| 23. | Arensky: An der Quelle in A, op. 46, no. 1 | 3:08 |

| 12 April 1899 o.s.; (C117) Russia | ||

| 24. | Arensky: Unidentified composition | 3:30 |

| 12 April 1899 o.s.; (C107) Russia | ||

SANDRA DROUCKER§ (1876–1944) | ||

| 25. | Arensky: Etude in F-sharp, no. 13 from 24 Morceaux Charactéristiques, op. 36 | 2:42 |

| 18 February 1898 o.s.; (C135) Russia | ||

| 26. | Chopin: Prelude in F-sharp Minor, op. 28, no. 8 | 2:19 |

| 16 September 1898 o.s.; (C134) Russia | ||

VLADIMIR WILSCHAW† (1868–1957) | ||

| 27. | Godard: En Courant in G-flat, no. 1 from 6 Morceaux, op. 53 | 1:49 |

| Ca. 1890s; (C144) Russia | ||

EGON PETRI (1881–1962) | ||

| 28. | “Free Improvisation”* | 3:02 |

| October 1923; (C106) Vevey, Switzerland | ||

| 29. | Unidentified composition | 2:46 |

| October 1923; (C104) Vevey, Switzerland | ||

| 30. | Unidentified composition | 1:22 |

| October 1923; (C105) Vevey, Switzerland | ||

| 31. | Unidentified composition | 1:56 |

| October 1923; (C105) Vevey, Switzerland | ||

PAUL JUON† (1872–1940) | ||

| 32. | Juon: Variation 4 from the second movement of Sonata for Violin and Piano, op. 7 | 2:12 |

| 26 February 1911; (C162) Germany | ||

LEONID KREUTZER (1884–1953) | ||

| 33. | Liadov: Etude in F, op. 37* | 1:41 |

| 1915; (C141) Germany | ||

| 34. | Chopin: Mazurka in G Minor, op. 67, no. 2 | 1:10 |

| 1915; (C141) Germany | ||

| 35. | Juon: Humoresque in F, no. 3 from 6 Klavierstücke, op. 12* | 2:29 |

| February (?) 1915; (C158) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| ||

| CD 2: (76:03) | ||

LEONID KREUTZER and PAUL JUON† | ||

| 1. | Juon: Tanzrhythmen, op. 41, no. 3 (Allegretto grazioso) | 1:30 |

| 1915; (C159) Germany | ||

| 2. | Juon: Tanzrhythmen, op. 41, no. 2 (Vivace molto) | 1:15 |

| 1915; (C159) Germany | ||

SERGEI TANEYEV† and LEO CONUS† (1871–1944) | ||

| 3. | Leo Conus: Suite for Piano Four-Hands | 4:12 |

| 14 December 1893 o.s.; (C126) Russia | ||

SERGEI TANEYEV† and PAUL PABST† | ||

| Arensky: Suite No. 2 for Two Pianos, op. 23 (“Silhouettes”): | ||

| 4. | No. 1: “Le Savant” | 2:12 |

| 14 December 1892 o.s.; (C127) Moscow | ||

| 5. | No. 3: “Polichinelle” | 3:18 |

| 14 December 1892 o.s.; (C111) Moscow | ||

| 6. | No. 4: “Le Rêveur” | 3:27 |

| 14 December 1892 o.s.; (C130) Moscow | ||

INSTRUMENTAL | ||

JULES CONUS (1869–1942)†, violin | ||

| 7. | Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen, op. 20, no. 1 | 1:06 |

| 4 October 1892 o.s.; (C191) Russia With unidentified pianist |

||

| 8. | Bach: Partita No. 3, in E, BWV 1006 – Minuet 1 | 1:26 |

| 4 October 1892 o.s.; (C191) Russia | ||

| 9. | Chopin-Sarasate: Nocturne in E-flat, op. 9, no. 2, | 3:53 |

| 7 April 1894 o.s.; (C189) Russia With Paul Juon, piano |

||

ANTON ARENSKY†, piano; JAN HRÍMAL݆ (1844–1915), violin; and ANATOLY BRANDUKOV (1856–1930), cello: | ||

| Arensky: Piano Trio No. 1 in D Minor, op. 32 | ||

| 10. | First movement - Allegro moderato | 4:39 |

| 10 December 1894 o.s.; (C42) Russia | ||

| 11. | Second movement - Scherzo: Allegro molto | 3:27 |

| 10 December 1894 o.s.; (C43) Russia | ||

| 12. | Third movement - Elegie: Adagio | 3:30 |

| 10 December 1894 o.s.; (C44) Russia | ||

JASCHA HEIFETZ (1901–1987), violin and WALDEMAR LIACHOWSKY (1874–1958), piano | ||

| 13. | Cui: Orientale, from Kaleidoscope, op. 50* | 2:51 |

| 4 November 1912; (C192) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 14. | Cui: Orientale, from Kaleidoscope, op. 50* | 2:57 |

| 4 November 1912; (C193) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 15. | Mozart-Auer: Gavotte in G, from Idomeneo* | 2:49 |

| 4 November 1912; (C194) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 16. | Popper-Auer: Etude, op. 55, no. 1 “Spinnlied”* | 2:37 |

| 4 November 1912; (C195) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 17. | Kreisler: Schön Rosmarin* | 2:23 |

| 4 November 1912; (C197) Grunewald, Germany | ||

EDDY BROWN (1895–1974), violin and JULIUS BLOCK† (1858–1934), piano | ||

| 18. | Tartini-Kreisler: Variations on a theme of Corelli | 2:58 |

| 27 December 1914; (C200) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 19. | Kreisler: La Chasse in the style of Cartier* | 2:35 |

| 27 December 1914; (C211) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 20. | Kreisler: Andantino in the style of Martini* | 2:55 |

| 6 December 1914 [per announcement]; (C207) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 21. | Kreisler: Liebesleid* | 3:10 |

| 6 December 1914 [per announcement]; (C202) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 22. | Haydn-Burmester: Minuet in F, from Symphony No. 96 | 3:05 |

| 27 December 1914; (C209) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 23. | Beethoven-Burmester: Minuet No. 2 in G, 167, WoO 10 | 3:04 |

| 27 December 1914; (C212) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 24. | Schumann-Auer: Vogel als Prophet, from Waldscenen, op. 82 | 3:10 |

| 27 December 1914; (205) Grunewald, Germany | ||

| 25. | Juon: Berceuse, op. 28, no. 3* | 2:58 |

| 27 December 1914; (C210) Grunewald, Germany | ||

JOSEPH PRESS (1881–1924), cello and MICHAEL PRESS (1872–1938), violin | ||

| 26. | Handel-Halvorsen: Passacaglia in G Minor, from Harpsichord Suite No. 7, HWV 432* | 2:58 |

| Recording date unknown; (C198) | ||

CHORAL | ||

THE CHOIR OF THE SYNODICAL SCHOOL OF MOSCOW, chorus, with unidentified conductor | ||

| 27. | Rachmaninoff: Spiritual Concert | 1:38 |

| 12 December 1893 o.s.; (C40)2 Hall of the Synodical School of Moscow | ||

| ||

| CD 3: (79:09) | ||

VOCAL | ||

MADAMOISELLE NIKITA (LOUISA MARGARET NICHOLSON)† (1872–unknown), soprano and PYOTR SCHUROVSKY† (1850–1908), piano | ||

| 1. | Donizetti: Quando rapito, from Lucia di Lammermoor | 2:57 |

| 19 February 1890 o.s.; (C62) St. Petersburg | ||

| 2. | Verdi: Ernani, involami, from Ernani | 3:12 |

| 22 November 1891 o.s.; (C63) Moscow | ||

| 3. | Composer unidentified: La Zingara | 2:20 |

| 19 February 1890 o.s.; (C59) St. Petersburg | ||

| 4. | Composer unidentified: At the Fountain | 2:29 |

| 19 February 1890 o.s.; (C60) St. Petersburg | ||

| 5. | Chopin: Nocturne in E-flat, op. 9, no. 2, arranged for voice and piano | 3:02 |

| 22 November 1891 o.s.; (C61) Moscow | ||

VASILY SAMUS† (1849–1903), tenor and unidentified pianist | ||

| 6. | Dargomïzhsky: I am in love, my maiden, my beauty | 1:33 |

| 15 February 1890; (C74) the Hall of the St. Petersburg Conservatory | ||

| 7. | Rubinstein: Longing, op. 27, no. 9 | 2:28 |

| 1890; (C75) Russia | ||

| 8. | Tchaikovsky: Don Juan’s Serenade, op. 38, no. 1 | 2:32 |

| 1890; (C77), Block’s Apartment, Moscow | ||

ADELE BORGHI† (1860–unknown), mezzo-soprano and unidentified pianist | ||

| 9. | Bizet: Habanera from Carmen | 1:33 |

| 1891; (C67) Russia | ||

MARIA KLIMENTOVA-MUROMTZEVA† (1857–1946), soprano and SERGEI TANEYEV†, piano | ||

| 10. | Bizet: Pastorale | 2:40 |

| 4 February 1891 o.s.; (C65) Moscow, History Museum’s main lecture hall | ||

| 11. | Tchaikovsky: Do not leave me!, no. 4 from 6 Romances, op. 27 | 2:48 |

| 5 February 1891 o.s.; (C66) Moscow, History Museum’s main lecture hall | ||

| 12. | Unidentified composition | 0:47 |

| 4 February 1891 o.s.; (C64) Moscow, History Museum’s main lecture hall | ||

| 13. | Schumann: Widmung, no.1 from Myrthen, op. 25 | 2:06 |

| 4 February 1891 o.s.; (C64) Moscow, History Museum’s main lecture hall | ||

EUGENIA JURJEVNA WERDAN (dates unknown)†, mezzo-soprano and unidentified pianist | ||

| 14. | Grieg: Ich liebe dich, op. 5, no. 3 | 1:25 |

| 14 November 1892 o.s; (C52) Moscow | ||

| 15. | Cui: Mai, no. 7 from Musical Pictures, op. 15 | 1:48 |

| 14 November 1892 o.s; (C52) Moscow | ||

| 16. | Tchaikovsky: Legend, no. 5 from 16 Songs for Children, op. 54 | 3:25 |

| 14 November 1892 o.s.; (C55) Moscow | ||

NIKOLAI FIGNER (1857–1918), tenor and unidentified pianist | ||

| 17. | Cui: I remember the evening | 2:04 |

| 31 March 1891 o.s.; (C88) Russia | ||

MARIA IVANOVNA GUTHEIL (dates unknown)†, soprano and unidentified pianist | ||

| 18. | Rubinstein: Sail | 2:12 |

| 10 January 1894 o.s.; (C68) Moscow, Physics Lecture Hall, Moscow University | ||

| 19. | Davydov: And night, and love, and moon | 2:49 |

| 10 January 1894 o.s.; (C69) Moscow, Physics Lecture Hall, Moscow University | ||

| 20. | Rubinstein: Longing, op. 27, no. 9 | 2:46 |

| 10 January 1894 o.s.; (C70) Moscow, Physics Lecture Hall, Moscow University | ||

LAVRENTII DONSKOI† (1857 or 1858–1917), tenor and unidentified pianist | ||

| 21. | Rimsky-Korsakov: Berendey’s cavatina from The Snow Maiden | 2:42 |

| 8 November 1894 o.s.; (C86) Russia | ||

| 22. | Rubinstein: O pechal I toska from Nero | 3:26 |

| 8 November 1894 o.s.; (C85) Russia | ||

EVGENY DOLININ† (1873–1918), tenor and unidentified pianist | ||

| 23. | Wagner: In fernem Land from Lohengrin | 3:40 |

| 10 December 1898 o.s.; (C93) Block residence, assumed St. Petersburg | ||

THERÉSÈ LESCHETIZKAYA-DOLININA† (1873–1956), soprano and unidentified pianist | ||

| 24. | Unidentified composition | 1:32 |

| 26 November 1898 o.s.; (C97) St. Petersburg | ||

| 25. | Godard: Chanson de Florian | 1:36 |

| 26 November 1898 o.s.; (C97) St. Petersburg | ||

ELIZAVETA LAVROVSKAYA† (1845–1919), soprano and unidentified pianist | ||

| 26. | Tchaikovsky: Lullaby in a Storm, no. 10 from 16 Songs for Children, op. 54 | 2:33 |

| Recording date unknown; (C51) Russia | ||

| 27. | Unidentified composition | 3:16 |

| 10 March 1892 o.s.; (C50) Russia | ||

ELENA GERHARDT (1883–1961), mezzo-soprano and ARTHUR NIKISCH (1855–1922), piano | ||

| 28. | Brahms: Blinde Kuh, no. 1 from [8] Lieder und Gesänge, op. 58* | 1:41 |

| 16 September 1911; (C100) Announced Berlin, but presumed to be Grunewald | ||

| 29. | Schubert: Wohin? no. 2 from Die schöne Müllerin | 2:11 |

| 16 September 1911; (C101) Grunewald, Germany | ||

SPOKEN WORD | ||

| 30. | ELENA GERHARDT and ARTHUR NIKISCH |

1:34 |

| 16 December 1911; (C352) Germany | ||

| 31. | LEO TOLSTOY (1828–1910) |

4:13 |

| 14 February 1895 o.s.; (C247) Russia | ||

| 32. | LEO TOLSTOY. With Countess Sofia Andreevna Tolstaya (Wife, 1844–1919), Tatiana L’vovna Tolstaya-Sukhotina (Daughter, 1864–1950), and Tatiana Mikhailovna Sukhotina-Albertini (Granddaughter, 1905–1996) |

2:37 |

| 14 February 1895 o.s.; (C245) Russia (Tolstoy and his wife) 2 November 1927; (C245) Vevey, Switzerland (Tolstoy’s daughter and granddaughter) |

||

| 33. | PYOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY† (1840–1893) and ANTON RUBINSTEIN† (1829–1894). With Elizaveta Lavrovskaya, Vasily Ilyich Safonov (1852–1918), Alexandra Ivanovna Hubert (1850–1937) and Julius Block |

1:10 |

| 4-10 January 1890 o.s.3; (C283) Moscow | ||

| 1 Cylinder 123 is not part of the collection at the Pushkin House. This track comes from a cylinder in the possession of the Antique Phonograph Monthly, which purchased it at auction along with other personal items of Block. We firmly believe this is Cylinder 123 listed in Block’s catalogue of cylinders, the “Phonogrammothek.” | ||

| 2 This cylinder is not part of the collection at the Pushkin House. This track comes from a cylinder in the possession of the Antique Phonograph Monthly. Based on Block’s catalogue of cylinders, the “Phonogrammothek” this cylinder could be numbers 39, 40, or 41. | ||

| 3 This cylinder does not contain an announcement and a date was not provided by the Institute of Russian Literature. The date indicated is based on the findings of P.E. Veidman, in her article, “P.I. Tchaikovsky. The Forgotten and the New” from “Vol. 2 Almanac” Tchaikovsky House-Museum in Klin. | ||

|

Some additional Block cylinders exist. The producers chose the cylinders to be included in this set based on the quality of the recording and the importance of the performer. “o.s.” (old style) refers to Julian Calendar dating Translations of the spoken portion of the cylinders may be found in Appendix 2, beginning on page 60. Dates spoken in Russian assumed to be o.s. † Only known recordings by this artist, although additional Block cylinders may exist. § Only other known “recordings” by this artist are piano rolls * Only known recording of this work by this artist | ||

Producer: John and John Anthony Maltese

Project Coordinators: Gregor Benko and Scott Kessler

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston

Audio Assistance: Dimitrios Antsos, Raymond Edwards, and J. Richard Harris

Photographs: Girvice Archer, Gregor Benko, Vivienne Christine Block, Institute of Russian Literature, Allen Koenigsberg, John and John Anthony Maltese, Charles Mintzer, and Barbara Tancil

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Translations: Charles Brand, Paulina Anderson-Dinitz, Marion Farber, Carsten Fischer, Margarita Glebov, Stephen Lehmann, Stephane Puille, and Hansjakob Werlen

Musical identification, booklet proofing, and biographical information: Stephen R. Clarke, Frank Cooper, Francis Crociata, Ueli Falett of the Internationale Juon Gesellschaft, Neal Kurz, Farhan Malik, Donald E. Manildi, Jay Reise, Gordon Rumson, and Jonathan Summers

Financial assistance: Association for Recorded Sound Collections; Davyd Booth; Henry Fogel; the University of Georgia’s Office of Vice President for Research; Peter Greenleaf; and the Estate of John Stratton, Stephen R. Clarke, Executor

While recording in Russia, help provided by: Members of the Phonogram Archive of the Institute of Russian Literature: Dr. Nicolai Nikolaevich Skatov, (Director of the Institute of Russian Literature and Associate Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences); Yuri Ivanovitch Marchenko (musicologist, Head of the Phonogram Archive); Vladimir Pavlovitch Schiff (engineer); Alexander Yurievitch Kastrov (musicologist); Translators: Yelena Pavlovna Frensis (Folk Department Assistant); Yelena Senkevitch (musicologist/consultant)

Special assistance: Bibliothekarin: Institut für Musikwissenschaft, Bern, Switzerland: Frances Maunder, Anselm Gerhard; Edison National Historic Site, West Orange, New Jersey: Gerald Fabris; Ethnologisches Museum, Phonogramm-Arkiv, Berlin, Germany: Susanne Ziegler; the New York Public Library: Rodgers and Hammerstein Archives of Recorded Sound, New York, New York: Sara Velez; Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut: Richard Warren

Marston is indebted to Galina Kopytova, the Jascha Heifetz biographer, who told the producers of this set about the existence of the Block cylinders and laid the groundwork for their transfer.

Marston would like to extend a special thanks to Gregor Benko and John Maltese, whose tireless and good-natured help spanning several years have made this extensive project not only possible, but pleasurable.

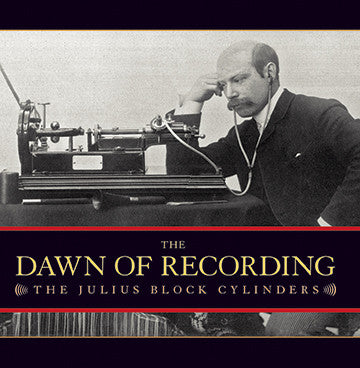

History of the Block Cylinders

Julius Block was born in Pietermaritzburg, Natal, (a British colony located in South Africa) in 1858. He had hopes of becoming a musician, but his father, a wealthy businessman who represented two American trading firms in Russia, insisted that he not waste his career on music. Reluctantly, Julius capitulated. Block proved to be an outstanding businessman and the family business in Russia flourished under his leadership, but music remained an essential part of his life. It was this confluence of music and business, linked with ingenuity, drive, persuasiveness, and charm that stimulated one man to create one of the world’s most important surviving musical legacies.

In 1889, the young entrepreneur, Julius Block, paid Thomas Edison a visit at his laboratory in Orange, New Jersey, in order to secure a phonograph. Block, an amateur pianist, had read about the tantalizing new invention in European newspapers and immediately recognized its amazing potential: a phonograph could preserve musical performances and capture oral history. Edison demonstrated the phonograph for Block, who eagerly asked to take one back to Russia. Edison agreed.

Upon his return to Russia, Block demonstrated the phonograph to Tsar Alexander III and his family; arranging this meeting was no small feat. The presentation was a resounding success. Intrigued, the Tsar asked to purchase a phonograph. Block wired Edison with the request, and soon Block personally presented the Tsar with his own phonograph, complete with a dedication plate from Edison.1 With this demonstration behind him, Block mounted a successful publicity campaign for his phonograph by organizing public exhibitions at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, the Moscow Conservatory, the Imperial Academy of Sciences, and other universities and scientific societies. These created a sensation and there was a keen curiosity in many circles throughout St. Petersburg and Moscow to witness this new invention firsthand.

Beginning in 1889, one of the earliest dates to record music, Block organized phonographic soirees, which resulted in his greatest accomplishment: documenting some of the most important artists and personalities of his time on cylinder. Within ten years, Block was able to demonstrate his cylinder machine to—and in many cases record—numerous luminaries who lived and passed through Moscow and St. Petersburg. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Leo Tolstoy, Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Anton Rubinstein were among these and each described his reaction to the phonograph in Block’s “Edison Album.” Tchaikovsky called it “the most surprising, most beautiful and most interesting invention of the end of the nineteenth century” Tolstoy predicted the phonograph, like the printing press, would herald a new “epoch in the history of humanity.” Rimsky-Korsakov, with some foresight, saw the possibility of using the phonograph “in a broadcast manner,” adding “” Rubinstein saw in the phonograph a boon to “the PERFORMING artists,” for now their “lamentations that their art is forgotten immediately after the execution are eliminated.” He added, “But ‘gare aux executants’!!!” (sic) (“Performers beware!!!”). This warning could, of course, mean at least two things: that recorded music might take the place of performers or that ephemeral memories of performances might be kinder than the harsh reality of recordings.

Rubinstein may have had the latter in mind when Block recorded snippets of a gathering he attended, probably early in January 1890.2 One by one, the guests—including Tchaikovsky (the only surviving cylinder in which he participates), the soprano Elizaveta Lavrovskaya, and the pianist Vasily Safonov (who had just become director of the Moscow Conservatory)—urged Rubinstein to play the piano. Lavrovkskaya sings some trills, Safonov introduces himself, Tchaikovsky pronounces: “Block is great, but Edison is even better!”—and then whistles into the recording horn. Rubinstein remained steadfast in his refusal to perform, but left posterity with a single recorded sentence; referring to the phonograph, Rubinstein said, “What a wonderful thing.” Luckily, others were not so reticent. Because of Block, we can eavesdrop on Josef Hofmann playing a year after Anton Rubinstein’s death; Paul Pabst, a Liszt pupil who died in 1897, performing his own solo transcriptions as well as piano four-hand with Leo Conus and Sergei Taneyev; Anton Arensky performing his own compositions, including excerpts from his famous D Minor Piano Trio in the year of its composition with violinist Jan Hřímalý and cellist Anatoly Brandukov; Maria Klimentova-Muromtzeva, who created the roles of Tatiana and Oksana in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin and Cherevichki, accompanied at the piano by Tchaikovsky’s pupil Taneyev; the great Russian mezzo-soprano Elizaveta Lavrovskaya, who recommended to Tchaikovsky that he compose an opera based on the story of Eugene Onegin; as well as Anna Essipova, Nikolai Figner, Paul Pabst, and many others.

Block moved to Germany in 1899. There is no evidence that Block recorded cylinders between 1901 and 1910, but significant recordings do survive from the years 1911 to 1915. These include the 11-year-old Jascha Heifetz one week after his sensational debut with Arthur Nikisch and the Berlin Philharmonic; Nikisch accompanying Elena Gerhardt; Paul Juon, a student of Arensky and Taneyev, playing his own compositions; Leonid Kreutzer, the pianist and teacher at the Berlin Academy of Music, playing four-hand piano with Juon as well as solos by Chopin, Liadov, and Juon; and the 19-year-old-violinist, Eddy Brown, who is accompanied by Block, playing Kreisler, Haydn, Beethoven, and others.

Block spent his final years in Vevey, Switzerland with his second wife, where he added Emanuel Moór and his wife, Winifred Christie-Moór to his circle of friends, which included Paul Juon, who was also living in Vevey. While living in Switzerland, Block recorded the pianist Egon Petri and the voices of the Moórs as they listened to Petri. In Vevey, Block also recorded the voices of Leo Tolstoy’s daughter and granddaughter. Julius Block died in 1934, in Switzerland.

During his lifetime, Block was quite aware of the importance of his collection. In fact, in his journal Block wrote, “…these are some of the treasures stored up in my phonogram library, and their value will increase with time.”2 He sent several of his cylinders to Edison with the hope that the inventor could preserve them by making moulds of the recordings. Such attempts failed.4 The cylinders that Block sent to Edison were evidently later destroyed in a fire. In 1930, Block began negotiations with the Phonogramm-Archive at the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin to preserve his cylinders. Three were turned over to the archive for galvanization that year, with plans to galvanize all the cylinders to assure their preservation. But Block’s death and financial considerations prevented that from happening. After Block’s death, his daughter Nancy donated 359 original wax cylinders to the Phonogramm-Archiv with a catalogue of the cylinders entitled, “Phonogrammothek.” Block’s large collection of musical scores and manuscripts went to Bern University in Switzerland (Bibliothekarin, Institut für Musikwissenschaft).5 According to Block’s son Walter, some of the cylinders also went to an archive in Warsaw, Poland. This would explain the disappearance of a number of cylinders Block mentions in his memoirs and essays. For example, Block refers to recordings of Leopold Auer and of the Eccles cello sonata played by Joseph Press, which are not listed in the “Phonogrammothek.”6 Most intriguingly, Block writes in another essay that he recorded the Tchaikovsky piano trio with Taneyev, Hřímalý, and Brandukov. He said that he recorded the trio specifically for a visit by Tchaikovsky on 7 November 1891, “as a surprise” for the composer. The day before, Tchaikovsky had conducted the premiere of his symphonic poem Voivode in Moscow. The composer was disappointed by the work’s reception and went into a great depression. The meeting at Block’s apartment, with Tchaikovsky’s brother Modest and several mutual friends, including Taneyev and Brandukov, was meant to lift his spirits. The evening began with dinner, but Tchaikovsky’s mood remained dark. After dinner, Block played the recording of his trio, as well as others. Tchaikovsky’s “gloom did not disappear until well on in the phonographic séance. Our maestro was so taken by some of the musical recordings that he continued to listen until the clock struck half past two.”7 If only we knew what other recordings Tchaikovsky listened to that night. Several recordings in this set were recorded before 7 November 1891. These include performances of Tchaikovsky compositions by both Klimentova-Muromtzeva (accompanied by Taneyev) and the tenor Samus. Could it be that Tchaikovsky listened to these very cylinders that night?

Many, including Block’s family, believed that all of the cylinders were destroyed during World War II. As his son Walter wrote in 1965: “Unfortunately, the collections in Warsaw and Berlin were destroyed during the second World War. But the collection in Bern is still preserved…”8 Amazingly, many of the Berlin cylinders survived; they had been evacuated to Silesia in 1944 to prevent their destruction.9 They were confiscated by the Russians after the war. The Berlin archive that originally housed the cylinders was located in what soon became Soviet-controlled East Berlin, and it disappeared behind the Iron Curtain. The cylinders themselves were eventually taken to Leningrad where they came to be housed at the Institute of Russian Literature—more commonly known as the Pushkin House (Pushkinsky Dom). Outside the Soviet Union, everyone assumed that the cylinders were forever lost.

Interest in the Block cylinders occasionally resurfaced. Block’s son Walter gave a copy of his father’s memoirs to Yale University in 1965. The book contained detailed information about the cylinders. In the early 1990s, a small collection of 24 Block cylinders, together with photographs, papers, and ephemera relating to them appeared and were auctioned in London. The noted New York collector Allen Koenigsberg bought them and wrote an article about the Block cylinders in the Antique Phonograph Monthly in 1992.

Within Russia, musicologists were aware that the Block cylinders existed. In the 1990s, news began to filter out to the West about the lone Tchaikovsky cylinder. But only now, as the result of a chance discovery of the remaining cylinders in 2002, can the treasures of the Pushkin House be heard by all.

©John and John Anthony Maltese, 2008

1 Julius Block, Mortals and Immortals: Edison, Nikisch, Tchaikofsky, Tolstoy. Episodes Under Three Tzars. Unpublished manuscript, distributed by Yale University Library, New Haven, Connecticut. H.S.R., ML300 .4 B651 M84, with the compliments of Walter E. Block, 1965, Bermuda, p. 16.

2 This recording is perhaps the most curious cylinder in Block’s collection and additional information is devoted to it in the article, “A Note on the Recordings.”

3 Block, Mortals and Immortals, p. 22.

4 Allen Koenigsberg, “The Russian Connection: Julius H. Block Meets the Czar,” Antique Phonograph Monthly, Vol. 10, no. 4, Issue No. 88, p. 9.

5 It is possible that some Block cylinders also survive in Bern. The Bibliothekarin has several uncatalogued cylinders that may be a part of the Block Collection.

6 Block, Mortals and Immortals, p. 22.

7 Essay by Julius H. Block in Alexander Poznansky, ed., Tchaikovsky Through Others Eyes, translated from Russian by Ralph C. Burr, Jr. and Robert Bird, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999, 160–161.

8 Block, Mortals and Immortals, “Introduction,” Walter E. Block.

9 Letter from Dr. Susanne Ziegler (of the Phonogramm-Archiv, Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin) to John Anthony Maltese, 26 May 2003.

The Block Cylinders and

the Dawn of Recording

In 1889, in the months just after Edison perfected the first viable sound recording device, the inventor’s agent Theo Wangemann inscribed a number of unique cylinder recordings of great musicians. Most famous is the legendary (some would say notorious) Brahms cylinder, on which the composer can be heard performing one of his own Hungarian Dances. Played so much it was worn out long before it was copied onto a 78 rpm disc, this earliest of all composer recordings is the object of controversy, with some claiming the remaining sound is so faint and distorted that it sadly reveals little of musical value, while others have written extravagant essays about Brahms’s playing. Most of the other cylinders incised by Wangemann, recordings of Hans von Bülow, Lilli Lehmann, Theodore Thomas, and other important musicians, have apparently been lost to history. Wangemann was not the only pioneer making celebrity cylinders—in his Berlin home the prodigy Josef Hofmann recorded tenor Jean de Reszke and others in the early 1890s, while at the same time Polish-born novelist Joseph Conrad made cylinders of his friends Paderewski and soprano Marcella Sembrich, and a New York City doctor assembled a library of cylinders that included several played by his friend, the pianist Leopold Godowsky. These too seem to have disappeared from history.1

At the same time in Russia, the farsighted businessman Julius Block was recording cylinders. Consumed with interest in the newly invented phonograph, Block was determined to record and preserve the piano playing of pianist Anton Rubinstein. Alas! He never succeeded. It was a huge loss to posterity, but history owes Block a great debt for the many other cylinders he did record, and which have miraculously survived. A remarkable 1922 letter from Edison to Block has also survived. Block had written to the inventor, offering to send these cylinders so Edison’s company could preserve and even issue them. Edison’s answer makes it clear he had no interest in Block’s cylinders.

Among these Block cylinders are the earliest surviving recordings ever made of music by Bach, Wagner, Chopin, Schumann, Donizetti, Bizet, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, and others. There are also recordings by the composers Arensky, Taneyev, and Pabst. Paul Juon and Leo Conus were also captured playing their own compositions, and the singing and playing of musicians who created operatic roles and premiered major works by Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Anton Rubinstein, and Rachmaninoff were preserved.

Block’s cylinders provide a unique glimpse into Tchaikovsky’s musical circle with performances by eight artists who had premiered his works, including his pupil Taneyev, who gave the premiere of the Second Piano Concerto, and completed the Third Concerto after Tchaikovsky’s death. These are Taneyev’s only recordings, and his 1891 cylinder enjoys the status of being the earliest surviving recording by a major soloist, if we agree that Brahms was not a major soloist.

Among the most satisfying cylinders that Block recorded are those of the Liszt pupil Paul Pabst, who died in 1897 at the age of 43. By then Pabst’s paraphrases of Tchaikovsky melodies were already famous. His 1895 cylinder of his own paraphrase of the Sleeping Beauty Waltz is probably the first great piano recording in history, enjoying amazing sound quality that successfully showcases the grandeur and virtuosity of his pianism. No wonder that both Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff had dedicated compositions to him. The cylinder is a fitting tribute to his friend Tchaikovsky, who had died 26 months earlier. Together, Pabst’s recordings are a major addition to the discography of nineteenth century pianists. Obviously a very great virtuoso in the Liszt/Rubinstein tradition, Pabst’s passionate reading of Schumann’s “Chopin” section from Carnaval might be the most lyrical Schumann playing ever captured. His cylinders, the only recordings of this neglected Liszt pupil, include the first-known recordings of works by Chopin and Schumann.

Pabst and Sergei Taneyev were recorded playing movements from Arensky’s Silhouettes for two pianos, representing three titans from the Moscow Conservatory. In 1892, when these recordings were made, Taneyev was teaching counterpoint at the Conservatory (which he had directed from 1885 to 1889), while Pabst taught piano, and Arensky taught composition. Their pupils included such luminaries as Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, Medtner, and Glière.

Another important pianist whose playing would have been lost without Block’s efforts is Anna Essipova, who had some coaching with Liszt but was really the creation of Theodor Leschetizky, who became her husband. Her 1898 cylinder of a gavotte by Benjamin Godard is less well recorded than Pabst’s cylinders, but shows her to have been an elegant stylist with a distinct and attractive musical personality. Her only other recordings are unreliable Welte piano rolls. Essipova’s daughter by Leschetizky, the soprano Therésè Leschetizkaya, married the tenor Evgeny Dolinin, who sang in the premieres of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sadko (1897) and The Tale of Tsar Saltan (1900.) Neither recorded otherwise. Dolinin’s sole 1898 Block cylinder is the earliest surviving recording of music by Wagner. If Thérèse was remembered before these cylinders were discovered, it was because she later became the teacher of the musical philanthropist Alice Tully. An Essipova student, Leonid Kreutzer, who studied piano with her and composition with Glazounov at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, was captured in his earliest known recordings.

Several of the singers Block recorded had close ties to Tchaikovsky, and two had important links to the opera Eugene Onegin. The great mezzo-soprano Elizaveta Lavrovskaya, one of the stars of the Mariinsky Theatre, actually suggested the idea of turning Pushkin’s novel into an opera to Tchaikovsky. He dedicated his Six Romances, op. 27 (1875) to her. Soprano Maria Klimentova-Muromtzeva had created the role of Tatiana at the premiere of Eugene Onegin in 1879. She also created the role of Oksana in Cherevichki in 1887. Each recorded a Tchaikovsky song, with Taneyev accompanying Klimentova-Muromtzeva. These are the only known recordings of both singers. Tenor Nikolai Figner sang in the premieres of Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades (1890) and Iolanta (1892). Block’s 1891 cylinder of Figner was recorded a decade before the tenor’s first commercial recordings.

The cylinder of Adele Borghi, recorded in 1891 singing the “Habanera” from Carmen (just 19 years after the opera’s premiere) is faint, but she was the most famous Carmen of her day. It is the first recording ever made of music from Carmen. Much more vivid are the cylinders recorded in 1890 of “Mlle. Nikita,” an American soprano (Louisa Margaret Nicholson) who had a sensational career for several years in Europe and Russia. She took Russia by storm in 1889, where she returned in 1890 when the first of these cylinders were made, and again in 1895, when she was accompanied by the young pianist Harold Bauer. Nicholson was reputed to have received 2,000 fan letters per season and Massenet begged her to sing his Manon, yet a bicycle accident in 1897 crushed her throat and ended her career. Nikita dropped from history—her fate and death date unknown. These recordings suggest that she deserves attention. Perhaps the most important of her cylinders is a decorated rendition of Lucia’s mad scene, accompanied at the piano by the composer/ conductor Pyotr Schurovsky (his only known recording), who had studied with Tchaikovsky, Moscheles, and Litolff, and frequently conducted at the Bolshoi Theatre.

In 1890 Block also recorded four cylinders of the tenor Vasily Samus, who taught voice at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. His student there, tenor Lavrentii Donskoi, was recorded in 1894 during his own tenure at the Bolshoi Theatre. Donskoi had also studied at the Free Music School co-founded by Rimsky-Korsakov, whose aria he sings. There are also cylinders by two mysterious singers about whom we have not found biographical information: soprano Maria Ivanovna Gutheil (definitely not the famous Mahler singer, Marie Gutheil-Schoder) who Block recorded singing in a large hall in 1894, and mezzo-soprano Eugenia Jurjevna Werdan, recorded two years earlier. These are the only known recordings of these singers, as well as the first recordings ever made of music by Bizet, Donizetti, Tchaikovsky, and Verdi.

The great pianist Josef Hofmann’s cylinders for Block were made in 1895 just after his sensational Russian debut, and then in 1896 after a concert in Moscow at which the 19-year-old Hofmann honored his recently deceased teacher, Rubinstein. They include two works by Rubinstein and one by Mendelssohn that Hofmann didn’t otherwise record, as well as Wagner’s “Magic Fire Music,” which he did record in 1923, offering an opportunity to compare versions.

Block himself was a musician, and he can be heard accompanying cylinders made in 1914 in Germany of the 19-year-old violinist Eddy Brown, whose few recordings are much sought after by collectors. These are the earliest surviving recordings of the American violinist, a fellow Auer pupil with Heifetz. The Juon piece and the three original Kreisler compositions are new to Brown’s discography. Brown speaks on all but the last cylinder. These are also the only cylinders in which Block performs.

Two years earlier an even greater fiddler recorded for Block. His recordings of the 11-year-old Jascha Heifetz were made one week after the prodigy’s sensational debut with Arthur Nikisch and the Berlin Philharmonic. Little Jascha speaks on the cylinders, as does his father. All of the compositions are new to Heifetz’s discography, and they include a performance of “Schön Rosmarin” composed by his idol, Fritz Kreisler, who had accompanied Heifetz in the same piece six months earlier. These recordings pre-date Heifetz’s first Victor recordings by five years. His accompanist, Waldemar Liachowsky, a Schnabel pupil who was born in Russia, later accompanied many violinists, including Kreisler, Mischa Elman, Maud Powell, and Carl Flesch.

These were not, however, the earliest recordings of the violinist or even of a prodigy, for Heifetz had recorded three commercial discs a year earlier in Russia in 1911. Cellist Joseph and violinist Michael Press also made a Block cylinder together, the only recording of the Press brothers performing with each other. Both studied at the Moscow Conservatory—Joseph with Alfred Glehn and Michael with Jan Hřímalý. Halvorsen had made his famous arrangement of the Handel in 1894. Though undated, this cylinder was probably made shortly thereafter and is surely the first recording of this work.

Block documented the musical circle of Anton Arensky as well as that of Tchaikovsky. He was especially proud of the recordings he made of Arensky playing his own compositions, the first systematic effort in history to preserve any composer’s interpretations of his own works. Block began the project in 1892 and therefore predated the Gramophone Company’s recordings of composers such as Grieg in 1903 and Saint-Saëns in 1904 by 11 years. Arensky recorded several of these pieces in the year of their composition. Perhaps the greatest achievement of Block’s project is the set of recordings he incised in 1894 capturing Arensky playing the piano in his Trio No. 1 in D Minor, one of the most beloved chamber works in the repertoire, recorded just months after the Trio was composed. Though not a complete performance, these cylinders contain substantial sections of the first three movements. The fourth movement was recorded, but does not survive. In the performance we hear the only recordings of Arensky and violinist Hřímalý, who taught at the Moscow Conservatory from 1869 to 1915, and who premiered Tchaikovsky’s string quartets number 2 (1874) and 3 (1876) and piano trio (1882); his passionate performances of the Trio were legendary. , who premiered Rachmaninoff’s two piano trios (1892 and 1893) and cello sonata (1901, dedicated to him) and Tchaikovsky’s Pezzo capriccioso, Op. 62 (1889), which was also dedicated to him. Hřímalý and Brandukov enjoyed reputations as great artists; now it is verified.

Jules Conus was a successful violinist/composer who in 1892 had just returned from a period as associate concertmaster of the New York Symphony. His own violin concerto, dedicated to his teacher Hřímalý, has remained in the repertoire. He recorded two selections for Block in 1892, the first solo violin recordings ever made, including the earliest recorded performance of Bach. The young composer Paul Juon (who had also studied violin with ) accompanies Conus in a third, 1894 recording—the same year that Conus premiered Rachmaninoff’s second piano trio with the composer and the cellist Anatoly Brandukov. These are the only known recordings of Jules Conus.

Paul Juon was nicknamed “the Russian Brahms,” and Block’s cylinders are his only known recordings. His solo cylinders document him playing his own works when he was head of the composition department at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin in 1911. His earlier, 1894 cylinder as an accompanist to Jules Conus was recorded when Juon was a student at the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied with Arensky and Taneyev. Juon’s compositions are also performed by other musicians recorded by Block, and he was recorded playing excerpts from his own Tanzrhythmen with pianist Leonid Kreutzer in 1915. Jules Conus’s brother Leo was a pianist whose playing was documented by Block performing his own Suite for four hands with his teacher Taneyev. Leo Conus had also studied with Arensky. This is his only known recording.

Block secured pianist Vladimir Wilschaw’s only recording. Wilschaw was a student of Arensky, Pabst, and Taneyev at the Moscow Conservatory, and a lifelong friend to Rachmaninoff; their correspondence has provided three generations of scholars with rich source material. Sandra Droucker, an Anton Rubinstein pupil, is represented by her only recordings aside from Welte piano rolls.

Besides Nikolai Figner, Block also recorded cylinders by two other artists who did make commercial recordings: the lieder singer Elena Gerhardt accompanied on the piano by the conductor Arthur Nikisch with whom she was romantically linked. Block captured that duo in one Brahms song they did not record commercially.

In all, the surviving Block cylinders document the work of 21 composers and musicians who did not otherwise record, as well as one of Gerhardt and Nikisch speaking. Block also recorded the voice of Leo Tolstoy, whose cylinder gives a fascinating glimpse of the Tolstoy family. Dating from 1895, it is the first recording Tolstoy made, reading from his work ”The Repentant Sinner.” It also contains the voices of Tolstoy’s wife, Countess Sophia Andreyevna, as well as a recording of the Tolstoys’ daughter and granddaughter, inscribed on the same cylinder 33 years later at Block’s home in Vevey, Switzerland. Block’s final musical cylinders, made in 1923, captured the earliest recordings of pianist Egon Petri, at Block’s home in Vevey in the presence of composer Emanuel Moór.

Block’s oddest, and some might say the most important cylinder is presented last on our three-CD set. It contains the voices of several people including Anton Rubinstein and Tchaikovsky. It is unlike any other cylinder in the Block collection and a detailed discussion is devoted to it in the article, “A Note on the Recordings.”

None of the above facts, however, can emphasize enough the musical importance of these recordings. Taneyev’s 1891 cylinder of Mozart’s Fantasie C Minor K. 396, shows that he played with a freedom and elasticity of tempo almost unknown today. More than 100 years have passed since Taneyev made that cylinder, but less than a 100 years had passed from the time of Mozart’s death to Taneyev’s recording. The Taneyev cylinder and several others presented here contain powerful evidence to help address questions about the evolution of performance practices and styles. Schumann had been dead for less than 40 years when Pabst recorded excerpts from his Carnaval, about the same amount of time that has passed between the writing of these words and Stravinsky’s death; Chopin had been dead a decade longer.

There is compelling reason to regard these recordings as the “Rosetta Stone” of nineteenth century musical performance practice.

© John Anthony Maltese and Gregor Benko, 2008

1 Transcriptions of two other cylinder recordings from 1889 do survive. These were made in Denmark of the bass Peter Schram (1819–1895) singing arias from Don Giovanni. The celebrated Mapleson cylinders of live opera performances were recorded at the Metropolitan Opera House between 1900 and 1904 and have been issued by their custodian, the New York Public Library.

BIOGRAPHIES

Arensky, Anton Stepanovich [Pianist, Composer, Conductor] (1861–1906). Born in Novgorod, Russia, Arensky studied composition with Rimsky-Korsakov at the St. Petersburg Conservatory (1879–1882). The Moscow Conservatory hired him upon his graduation, and he taught harmony and composition there until 1895. His students included Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Glière. In 1895, he succeeded Mily Balakirev as director of the Imperial Chapel in St. Petersburg, a coveted post that he held until 1901. Notorious for his heavy drinking and gambling, he fell ill with tuberculosis and died at a sanatorium in Finland at the age of 44. Arensky, described by the New Grove Dictionary as “one of the most eclectic Russian composers of his generation,” wrote over 70 works, including three operas, two symphonies, a ballet, violin and piano concertos, chamber music, songs, and works for the piano.

Block, Julius [Pianist, Businessman] (1858–1934). Born in Natal (a British colony located in South Africa), Block was raised in St. Petersburg where his father represented two American trading firms. Julius loved music and was a fine amateur pianist. He wanted to study at the Leipzig Conservatory, but his father stood in the way. After travels to London and the United States to further his education, Julius joined his father’s business in 1877 and took it over in 1888. Between them, he and his father introduced many inventions to Russia, including the cotton gin, the elevator, the bicycle, and the phonograph. Block moved to Berlin in 1899 and spent his last years in Switzerland. He recorded these cylinders with a phonograph that Thomas Edison gave him during a visit to the United States in 1889.

Borghi, Adele [Mezzo-Soprano] (1860–?). Relatively little is known about Borghi (not to be confused with Adelaide Borghi-Mamo). She was born in Italy and sang at La Scala where she originated the role of Lélio in Ponchielli’s Marion Delorme in 1885. She toured widely, appearing in Russia, Spain, Romania, and the United States. She was especially known for her interpretation of Carmen.

Brandukov, Anatoly Andreyevich [Cellist] (1856–1930). Born in Moscow, Brandukov studied there at the Conservatory from 1868 to 1877. He moved to Paris in 1878, where he played in Martin Marsick’s string quartet and performed the Saint-Saëns cello concerto with the composer conducting. He also performed with Liszt and Anton Rubinstein. He returned to Russia frequently and played the premieres of both of Rachmaninoff’s trios with the composer at the piano. He and Rachmaninoff also played the premiere of the cello sonata, which Rachmaninoff dedicated to him. Tchaikovsky dedicated his Pezzo Capriccioso, op. 62 (1889) to Brandukov, as well as an arrangement of the “Andante Cantabile” from his first string quartet, which Brandukov premiered in Paris with Tchaikovsky conducting. Brandukov became director of the Moscow Philharmonic School of Music and Drama in 1906, and taught at the Moscow Conservatory from 1921 until his death.

Brown, Eddy [Violinist] (1895–1974). Born in Chicago, Brown studied violin with Hubay and composition with Bartók and Kodály at the Budapest Conservatory (1904–1909). After hearing Brown’s 1909 London debut, Leopold Auer invited the 14-year-old to study with him at St. Petersburg. Brown agreed and stayed with Auer from 1910 to 1915. He made his Berlin debut in 1910 with Nikisch and the Philharmonic, and he played there often before making his U.S. debut in 1916. He gave the U.S. premiere of the Debussy sonata at Carnegie Hall in 1917. One of the first great American violinists, he recorded for Columbia, Odeon, and Royale. In the 1930s, he turned to a career in radio, becoming director of WOR and later WQXR in New York.

Conus [Konyus], Jules [Yuly Eduardovich] [Violinist, Composer] (1869–1942). Born in Moscow to a family of French musicians, Conus studied violin with Hřímalý and composition with Arensky and Taneyev at the Moscow Conservatory. He played in the Colonne Orchestra in Paris and was associate concertmaster of the New York Symphony for one season (1891–1892). He returned to Russia to teach violin at the Moscow Conservatory. There, he became a close friend of Rachmaninoff, who dedicated his Two Pieces, op. 6 to him in 1893. The next year he performed the premiere of Rachmaninoff’s second piano trio with Rachmaninoff and Brandukov. Conus is best remembered for his violin concerto, written in 1898 and dedicated to Hřímalý. Kreisler gave its U.S. and British premieres, and Heifetz later championed it. Conus lived in Paris from 1919 to 1939 before returning to Moscow. His son Boris married Rachmaninoff’s daughter Tatiana in 1932.

Conus [Konyus], Leo [Lev Eduardovich] [Pianist, Composer] (1871–1944). The brother of Jules, Leo was born in Moscow. He studied there at the Conservatory under Arensky and Taneyev. Like his brother, he was a close friend of Rachmaninoff. Conus arranged Tchaikovsky’s Pathétique symphony for piano 4-hands and played it with Taneyev for Tchaikovsky in 1893. Conus taught at the Moscow Conservatory from 1912 to 1920 and served as head of the piano department. He moved to Paris in 1921 and then immigrated to the United States in 1937. He settled in Cincinnati and taught there until his death.

Dolinin, Evgeny Ivanovich [Tenor] (1873–1918). Born in Simbirsk (currently Ulyanovsk), Russia, as Evgeny Shein, he later adopted the stage name Dolinin. He studied at the St. Petersburg Conservatory with Cotogni. Upon graduation he sang at the Mariinsky Theatre. He originated two Rimsky-Korsakov roles: Foma Nazarich in Sadko and Tsarevich Gvidon in The Tale of Tsar Saltan. He performed throughout Russia and appeared in Italy (1902), Prague (1904–1905), Budapest (1905), and Vienna (1906). He settled in Khar’kov, Ukraine where he taught at the College of Music. His wife was the soprano, Therésè Leschetizkaya (daughter of Theodor Leschetizky and Anna Essipova), who is also heard on these cylinders.

Donskoi, Lavrentii Dmitrievich [Tenor] (1857 or 1858–1917). Born into a peasant family in the village of Ushilovo in the Kostroma region of Russia, Donskoi moved to St. Petersburg in 1872. There he studied at the Conservatory with Samus and Everardi from 1877–1880. He then studied at the Free Music School, created by the so-called “Mighty Handful” (Balakirev, Borodin, Cui, Mussorgsky, and Rimsky-Korsakov), and was among Mussorgsky’s last pupils. He sang with the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow from 1883–1904. Donskoi was an accomplished actor and acclaimed as one of the best singers of his generation. He sang 78 roles in 69 different operas, performed at the Paris World’s Fair in 1900, received the title “Distinguished Singer of the Imperial Theatres” in 1909, and taught at the Moscow School of Music and Drama from 1907–1917.

Droucker, Sandra [Pianist] (1876–1944). Born in St. Petersburg, Droucker studied with Anton Rubinstein and made her debut in 1894. She toured Europe, appearing with Fürtwangler and other leading conductors. Her 1910 marriage to the pianist Gottfried Galston ended in divorce. She taught in Berlin, Munich, and Vienna, wrote a book about Rubinstein that was published in 1904, and made piano rolls for Welte-Mignon.

Essipova [Essipoff], Anna [Annette] Nikolayevna [Pianist] (1851–1914). Born in St. Petersburg, where she entered the Conservatory at the age of 13, Essipova studied first with Villoing and then with Leschetizky (to whom she was later briefly married). After her Moscow debut in 1871, Tchaikovsky took note of her exceptional technique and artistic expression. She met and played for Liszt in 1873 and began a period of extensive touring. She made her London debut in 1874, her Paris debut in 1875, and her U.S. debut in 1876. After 20 years of touring, she settled in St. Petersburg and taught at the Conservatory until her death. Her pupils include Barere, Borowski, Pouishnoff, Prokofiev, and Schnabel. She made piano rolls for Welte-Mignon, but the one cylinder in this collection is her only recording.

Figner, Nikolai [Tenor] (1857–1918). Born in the province of Kazan, Figner attended the Naval College in St. Petersburg and served in the Navy for six years. He later studied voice at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, but was told that he had no vocal talent. Undeterred, he traveled to Italy for further lessons and made his debut in Naples in 1882 in Gounod’s Philémon et Baucis. This led to successful appearances throughout Italy and Spain, followed by a season in South America where he sang in Aïda under the young Toscanini in 1886. He returned to Russia in 1887 and made his debut at the Mariinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg. He sang in the premieres of Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades (1890) and Iolanta (1892), and Napravnik’s Dubrovsky (1895) and Francesca da Rimini (1902). From 1910 to 1915, he directed the Narodny Dom Theatre in St. Petersburg. (Nikolai was the husband of the famous Italian soprano, Medea Mei-Figner.)

Gerhardt, Elena [Soprano and Mezzo-Soprano] (1883–1961). Gerhardt was born in Leipzig where she studied at the Conservatory with Marie Hedmont from 1900–1904. Her talent was such that the Conservatory’s director, Arthur Nikisch, accompanied Gerhardt at her debut recital on her 20th birthday. She sang briefly with the Leipzig Opera (1905–1906), but devoted most of her career to lieder and helped to perfect a style of lieder singing distinct from the operatic style used by most of her predecessors. Nikisch, with whom she was romantically involved, accompanied Gerhardt at her 1906 London debut, and the two made a series of records for G&T in 1907. Gerhardt made her U.S. debut in 1912. She left Germany in 1934 and settled in England. Her voice deepened to mezzo-soprano with time, and she gave recitals as late as 1953.

Gutheil, Maria Ivanovna [Soprano]. Almost nothing has been discovered about this soprano except that she studied with Elizaveta Lavrovskaya and that she is not the soprano Marie Gutheil-Schoder.

Heifetz, Jascha [Violinist] (1901–1987). Born in Vilnius, Heifetz entered the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1910. He studied first with Nalbandyan and then with Auer, who introduced Heifetz to Berlin at a private press matinee in May 1912. Among the many violinists in attendance was Heifetz’s idol, Fritz Kreisler, who accompanied Heifetz at the piano and then wrote: “Never in all my life have I witnessed such precocity.” Heifetz made his Berlin recital debut that same month, followed by a sensational debut with the Berlin Philharmonic under Nikisch on October 28. These cylinders were recorded exactly one week later. Heifetz made his U.S. debut at Carnegie Hall in 1917 and his London debut in 1920. He proceeded to take the world by storm, including Australia in 1921 and the Far East in 1923. He recorded extensively for Victor and Decca, and gave his final recital in Los Angeles in 1972.

Hofmann, Josef [Pianist] (1876–1957). Born in Krakow, Poland, Hofmann was one of the greatest pianists of all time. He toured extensively as a child prodigy, making his European debut in 1886 at age ten, and his U.S. debut a year later at the Metropolitan Opera House. In 1888 he retired from the concert stage when the heir of the Singer Sewing Machine fortune put up an enormous sum to insure the boy’s future education. Hofmann worked briefly with Moszkowski before becoming the only private pupil of Anton Rubinstein in 1892. He resumed his concert career in November 1894, the same month that Rubinstein died. Hofmann returned to the United States in 1898, and toured Europe and America widely, visiting South America in 1936. He was considered the preeminent pianist of his generation. In 1926 he became director of Philadelphia’s Curtis Institute of Music. Hofmann was also a prolific inventor (of shock absorbers for motor vehicles, piano improvements, medical devices, etc.) and held over 70 patents. He made his first cylinders during a visit to the Edison laboratory in 1888, but went on to leave few recordings over his long career, apparently sharing Rubinstein’s distrust of recording.

Hřímalý [Grzhimali], Jan [Ivan Voytekhovich] [Violinist] (1844–1915). Born in Pilsen, Hřímalý studied at the Prague Conservatory with Moritz Mildner. From 1862 to 1868 he served as concertmaster of the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. He also had a successful career as a soloist and chamber musician, performing in the premieres of Tchaikovsky’s string quartets number 2 (1874) and 3 (1876) and piano trio (1882). He taught at the Moscow Conservatory from 1869 to 1915, succeeding Ferdinand Laub as chief violin professor in 1874 and establishing himself as Moscow’s equivalent to Leopold Auer in St. Petersburg. Hřímalý’s scale studies are still widely used. His many students included Stanislaw Barcewicz, Issay Barmas, Jules Conus, Paul Juon, Lea Luboschutz, Alexander Moguilewsky, Alexander Petschnikoff, and Michael Press.

Juon [Yuon], Paul [Pavel Fedorovich] [Pianist, Composer, Violinist] (1872–1940). Born in Moscow of German and Swiss descent, Juon spent most of his life in Germany. He entered the Moscow Conservatory in 1889, studying violin with Hřímalý and composition with Arensky and Taneyev. Between 1894–1895, he studied composition at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin and won the Mendelssohn Prize. He returned briefly to Russia to teach violin and music theory at the Baku Conservatory, but settled in Berlin in 1897. In 1906, Joseph Joachim appointed him head of the composition department at the Hochschule für Musik, a post he held until 1934. He wrote a great deal of chamber music, as well as works for solo piano, orchestra, and several concertos. He was nicknamed “the Russian Brahms” and won the Beethoven Prize in 1929. He translated Arensky’s book on harmony into German in 1900, and published his own book on the subject the next year. He also translated Modest Tchaikovsky’s two-volume biography of Pyotr Tchaikovsky.

Klimentova-Muromtzeva, Maria [Soprano] (1857–1946). Born in the Kursk region of Russia and raised in Kiev, Klimentova studied at the Moscow Conservatory from 1875–1880. As a student, she sang Tatiana in the 1879 premiere of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin (a student production conducted by Anton Rubinstein). She made her debut at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow the following year as Marguerite in Faust, and sang there until 1889 when, at the peak of her career, she left over a conflict with the administration. She also originated the role of Oksana in the 1887 premiere of Tchaikovsky’s Cherevichki. Beginning in 1890, she taught at the Moscow Conservatory, where she worked with the director Constantin Stanislavsky to stage student productions.

Kreutzer, Leonid [Pianist] (1884–1953). Born in St. Petersburg, Kreutzer attended that city’s conservatory, where he studied piano with Essipova and composition with Glazounov. He was Sergei Rachmaninoff’s only piano student (the composer admitted to just mentoring and coaching others who claimed they were his piano students) and Kreutzer assisted Rachmaninoff and Siloti in preparations for the premiere of the composer’s Second Piano Concerto in 1901. Kreutzer moved to Berlin in 1908 and toured as a concert pianist. He taught at the Hochschule für Musik from 1921–1933, subsequently teaching at the Imperial Academy in Tokyo. Kreutzer recorded discs for Polydor and Japanese Columbia as well as making piano rolls. His students included Ernö Balogh, Karl Ulrich Schnabel, Wladyslaw Szpilman, and Alexander Zakin.

Lavrovskaya, Elizaveta Andreyevna [Mezzo-Soprano] (1845–1919). Born in Kashin, Lavrovskaya studied with Henriette Nissen-Saloman at the St. Petersburg Conservatory and with Pauline Viardot in Paris. She was a staple at the Mariinsky Theatre, and also sang at the Bolshoi. She toured widely, including the European continent and England. She had close ties to Tchaikovsky, who dedicated his Six Romances, Op. 27 (1875) to her and was the one who suggested Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin as a subject for an opera. Tchaikovsky described her suggestion in a letter to his brother Modest on 18 May 1877. At first, he wrote, the “idea seemed wild to me,” but later as he ate alone at a restaurant he thought about Lavrovskaya’s idea and grew more and more excited. He located a copy of Onegin, spent an “utterly sleepless night” reading it, and found a librettist to work on it the very next day. Lavrovskaya was appointed a voice professor at the Moscow Conservatory in 1888.

Leschetizkaya-Dolinina, Therésè [Soprano] (1873–1956). Born in St. Petersburg, Leschetizkaya was the daughter of Theodor Leschetizky and his second wife, Anna Essipova. She first studied piano, but after developing rheumatism in her right hand at age 16, she turned her attention to singing. In 1891 the eminent soprano Marianne Brandt took an interest in her voice and began to teach her singing. Therésè continued her studies with Desirée Artôt de Padilla, Madame Giraldoni, and later with Napravnik. She established a career as a concert singer and coach and became head of the vocal department at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where one of her students was the tenor Evgeny Dolinin, whom she married. She left Russia to escape the depredations of the Soviet government and moved to Vienna, teaching there from 1933–1939, before returning penniless to Paris with a different husband, a noted vocalist named Voskresensky. She taught at the Russian Conservatory in Paris. Her American student Miriam Carleton-Squires wrote: “...she never talks about the voice. In fact, she says there is no voice, that we make it through our will.” Leschetizkaya died in Paris.

Liachowsky, Waldemar [Pianist] (1874–1958). Waldemar Liachowsky was born in Stolptsy, Russia, in 1874. He immigrated to Berlin as a young man, received his academic and musical education there, and studied piano with Artur Schnabel. His first big break came as accompanist for Mischa Elman, one of the early child prodigies to come out of Russia. He traveled to America with Elman and accompanied him at his debut in Carnegie Hall in 1908 and in many recitals to come. Liachowsky became a prominent accompanist for numerous famous violinists, including Maud Powell, Fritz Kreisler, Jascha Heifetz, and Carl Flesch. He even accompanied Albert Einstein who was an amateur violinist. He married the lieder singer Paula Nivell, with whom he appeared on the concert stage. They had two sons, Henry and Rudolph, whom he sent out of Nazi Germany to safety in the U.S. Liachowsky himself immigrated to the U.S. in 1937, changed his name to Lea, and continued his musical career, coaching and accompanying young violinists and singers.

Nikisch, Arthur [Pianist, Conductor] (1855–1922). Born in Hungary, Nikisch attended the Vienna Conservatory where he studied the violin with Joseph Hellmesberger and composition with Felix Dessoff. Upon graduating in 1874, he joined the Vienna Court Orchestra where he played in the violin section. He became assistant conductor of the Leipzig Opera in 1878 and principal conductor the next year. His posts included music director of the Boston Symphony, the Budapest Opera, the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, and the Berlin Philharmonic. He also directed the Leipzig Conservatory.

Nikita (stage name of Louisa Margaret Nicholson) [Soprano] (1872– ?) Probably born in Kentucky, though some sources say Philadelphia, Nicholson studied in Washington, D.C. with her uncle M. C. Le Roy. She toured America in her pre-teens and was billed as “The Miniature Patti.” She continued her studies in Paris with the brother-in-law of Adelina Patti, Maurice Strakosch. She was much manipulated by the inflated schemes of her uncle and Strakosch, who floated the absurd story that she was abducted as an infant by an Indian chief named “Niki”. In 1889 she made her Russian debut and immediately became a favorite of the public as well as with composers and musicians. That same year she appeared in Moscow (Zerlina in Don Giovanni) and in concert at Covent Garden with Luigi Arditi conducting. She also sang leading roles in Germany and Paris. Her looks, charm, and extraordinary singing led to huge success in Europe, until a bicycle accident in 1897 crushed her throat and ended her career. She retired to life as a society figure in Paris. Despite her stardom in Europe and Russia, Nikita has been completely forgotten.

Pabst, Paul [Pianist, Composer] (1854–1897). Born in Königsberg, Germany (now Kaliningrad, Russia), Pabst first studied piano with his father. He later studied in Dresden and then with Anton Door in Vienna. He also spent time with Liszt at Weimar. Pabst joined the piano faculty of the Moscow Conservatory in 1878 at the invitation of Nikolai Rubinstein, and was elevated to professor of high degree in 1881 (joining Taneyev and Safonov)—a post he held until his untimely death. Pabst composed many works, including a piano concerto, a piano trio (dedicated to the memory of Anton Rubinstein), and numerous paraphrases based on Tchaikovsky’s music. In return, Tchaikovsky dedicated his Polacca de concert, op. 72, no. 7 to Pabst. Pabst also had ties to Rachmaninoff. He performed Rachmaninoff’s Suite No. 1 for two pianos, op. 5 with the composer shortly after its composition, and Rachmaninoff dedicated his Seven Pieces for piano, op. 10 to Pabst. His students include Nikolai Medtner, Alexander Goldenweiser, and Konstantin Igumnov.

Petri, Egon [Pianist] (1881–1962). Born in Hanover, Petri studied with Teresa Carreño in Berlin and later with Busoni, who became his mentor, in Weimar. He made his debut in Holland in 1902 and taught at the Royal Manchester College of Music from 1905–1911 and at the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin from 1921–1925. In 1923, the year these cylinders were made, he appeared in the Soviet Union, playing 31 times in 40 days to enormous acclaim. He was reportedly the first soloist from the West to perform there after the Revolution. He made his U.S. debut in 1932. He settled there in 1940, teaching at Cornell University and then Mills College in California. He collaborated with Busoni in an edition of Bach’s keyboard works. Among his many pupils are Eugene Istomin, Grant Johannesen, Ernst Levy, John Ogdon, and Earl Wild.

Press, Joseph [Cellist] (1881–1924). Born in Vilnius, Press studied at the Moscow Conservatory with Alfred Glehn and graduated in 1902. He had further studies with Casals and Julius Klengel. He performed widely both as a soloist and as a chamber musician. In 1906, he formed the Trio Russe with his brother, Michael, and Michael’s first wife Vera Maurina. They toured with great success throughout Russia and Europe. From 1916–1918 Press was professor of cello at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. In 1918 he moved to the Kiev Conservatory, and later to the Odessa Conservatory. He left Russia in 1921 and was offered a position as head of the cello department at the Berlin Conservatory, but he turned down that offer in order to tour the United States as soloist. He was well received in the U.S., and joined the faculty of the Eastman School of Music in 1922. He died suddenly of pneumonia at the age of 41 shortly before a scheduled Carnegie Hall recital. He recorded for Polyphon.

Press, Michael [Violinist] (1872–1938). Born in Vilnius, Press was a prodigy. He played first violin in the local theater orchestra at the age of ten and became its concertmaster at the age of 13. He entered the Moscow Conservatory, where he studied with Hřímalý. Press was appointed professor of violin at the Moscow Conservatory in 1901, and succeeded Hřímalý as chief violin professor in 1915. He narrowly escaped execution during the Russian Revolution and fled to Germany where he lived for several years. He made his U.S. debut in 1922, joined the violin faculty of the Curtis Institute in 1924 (serving as Carl Flesch’s assistant for one year), and taught at Michigan State College from 1928–1938. He was also a composer and conductor (guest conducting the Boston Symphony, among others). He recorded for acoustic Vox when he lived in Germany.

Rachmaninoff, Sergei [Composer, Pianist, Conductor] (1873–1943). Rachmaninoff was a 20-year-old Moscow Conservatory graduate whose pre-eminent talent had already been proclaimed by Arensky, Taneyev, and Tchaikovsky when the cylinder in this set was recorded. The work known variously as O Mother of God Perpetually Praying, Sacred Concerto, or Spiritual Concert, was composed in the summer of 1893. The three-part work for unaccompanied mixed chorus began the composer’s relationship with the Choir of the Synodical School of Moscow, which culminated 22 years later in the premiere of his choral masterpiece, All Night Vigil. The Sacred Concerto was not published or performed again in the composer lifetime.

Rubinstein, Anton Grigorevich [Pianist, Composer, Conductor] (1829–1894). Rubinstein is widely considered one of the greatest pianists of his time. He founded the St. Petersburg Conservatory, which along with the Moscow Conservatory (founded by Anton’s brother Nikolai) helped to establish Russia’s reputation for producing innumerable outstanding musicians. Rubinstein studied with Alexander Villoing (one of Moscow’s leading piano teachers) as a non-paying student. Under Villoing’s tutelage, Rubinstein played in the Salle Erard for an audience that included Frederic Chopin and Franz Liszt. Liszt advised Rubinstein to study composition in Germany, which he did in time. In Berlin, Anton and his younger brother Nikolai were supported by Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer, who arranged for their instruction in composition, theory, and other non-musical subjects.

Safonov, Vasily Ilyich [Pianist, Conductor, Director of the Moscow Conservatory] (1852–1918). Safanov studied with Theodor Leschetizky and Louis Brassin. He graduated from the St. Petersburg Conservatory in 1880 and taught there briefly before succeeding Taneyev as director of the Moscow Conservatory in 1889. He was the principal conductor of the Moscow branch of the Russian Musical Society from 1889–1905, and again from 1909–1911; the principal conductor of the New York Philharmonic from 1906–1909; and director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York from 1906–1909. He returned to Russia in 1909 where he resumed his concert work and played in chamber ensembles.

Samus, Vasily Maksimovitch [Tenor] (1849–1903). Samus attended the St. Petersburg Conservatory where he studied voice. He became an instructor there shortly after his graduation in 1877. He was elevated to Professor in 1886. Lavrentii Donskoi was his most prominent student.

Schurovsky, Pyotr Andreevich [Pianist, Composer, Conductor] (1850–1908). Schurovsky studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory with Tchaikovsky, with further studies under Ignaz Moscheles in Leipzig and Henry Charles Litolff in Paris. He conducted often at the Bolshoi Theatre, led the Berlin premiere of Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar, and wrote a book on conducting. He also published a collection of 85 national anthems, and wrote one for Thailand (which is still used). His other compositions include an opera, piano pieces, and nearly 30 songs (some dedicated to, and sung by, Nikolai Figner). He also wrote extensively as a music critic.

Taneyev, Sergei Ivanovich [Pianist, Composer] (1856–1915). Born in Dyudkovo, Russia, Taneyev studied composition at the Moscow Conservatory with Tchaikovsky, and piano with Nikolai Rubinstein. When he graduated in 1875, he was the first in the history of the Conservatory to win the gold medal for both composition and piano performance. He made his official debut as a pianist in Moscow in January 1875, playing the Brahms D minor concerto. The following December he gave the Moscow premiere of Tchaikovsky’s first piano concerto. He also premiered Tchaikovsky’s second concerto in 1882 (with Anton Rubinstein conducting) and after Tchaikovsky’s death completed his third concerto. When Tchaikovsky resigned from the Moscow Conservatory in 1878, the 22-year-old Taneyev took over his harmony and orchestration classes, and when Nikolai Rubinstein died in 1881, Taneyev took over his piano classes. In 1883 Taneyev also took over the composition classes and in 1885 he became director of the Conservatory, a post he held until 1889. Thereafter he taught counterpoint at the Conservatory. A renowned polyphonist, Taneyev’s many compositions include symphonies, chamber music (including nine string quartets), an opera, and over 60 songs. Among his pupils were Scriabin, Rachmaninoff, Glière, Medtner, and Juon.

Tchaikovsky, Pyotr Ilyich [Composer] (1840–1893). Tchaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, Russia and although he showed early promise in music, he began a career as a civil servant. Without “giving up his day job” Tchaikovsky studied music at the new St. Petersburg Conservatory including instrumentation and composition under Anton Rubinstein, whom he idolized, but who never warmed up to him. Upon graduation, Tchaikovsky accepted the position of professor of harmony, composition, and history of music, but eventually was able to compose full-time, resulting in beloved masterpieces such as: Romeo and Juliet, the 1812 Overture, Marche Slave, the Nutcracker, Eugene Onegin, and the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Symphonies. Details of the mysterious circumstances surrounding his early death have launched novels, biographies, and movies, but the opening of archives in Russia in recent years, and this publication of recordings by his colleagues and friends, provide new and important resources for anyone interested in Tchaikovsky and his work.

Tolstoy, Count Leo [Lev] Nicholaevich [Novelist, Philosopher] (1828–1910). Born to nobility in Central Russia, Tolstoy is considered one of the greatest of all novelists, War and Peace and Anna Karenina being his most famous works. He was known for his views on nonviolence (Writings on Civil Disobedience and Nonviolence, The Kingdom of God is Within You) and was a great influence on Gandhi, who called Tolstoy “… the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced.” What is less known, is Tolstoy’s love of music. Tolstoy is quoted as saying, “Music is the shorthand of emotion,” and Tolstoy composed a simple waltz for piano, which survives today.

Eugenia Jurjevna Werdan [Mezzo-Soprano]. We have been unable to locate any biographical information about Werdan.

Wilschaw, Vladimir Robertovich [Pianist] (1868–1957). Born into a musical family (his father played violin at the Bolshoi Theatre), Wilschaw attended the Moscow Conservatory where he studied piano with Pabst. He also took classes with Arensky and Taneyev. At Pabst’s suggestion, he went to study with Busoni in Helsinki and then followed him to Boston for a year. Wilschaw was a lifelong friend of Rachmaninoff. He became a teacher, first at a women’s college, and then at the Moscow Conservatory.

A Note on the Discovery

of these Cylinders

The discovery of these cylinders is, for my father and me, the culmination of a search that lasted more than 30 years. It is also an event of remarkable serendipity. We first learned about these cylinders in 1971, when I was 11 years old. The source: the great American violinist Eddy Brown, who was a friend of my father’s. Brown made cylinders for Julius Block in Berlin in December 1914, and he told us that Jascha Heifetz had also recorded cylinders around the same time. Brown even claimed to have recorded duets with Heifetz. He and Heifetz had both studied with Leopold Auer at the St. Petersburg Conservatory in Russia, and also at Auer’s summer school in Loschwitz, Germany (where Heifetz was stranded in 1914 at the start of World War I).