| Total Time: 76:48 | ||

| 1. | SEMIRAMIDE: Bel raggio (Rossini) | 2:17 |

| July 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone T9139 | ||

| 2. | IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: Io sono docile (Rossini) | 2:37 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone Q9204 | ||

| 3. | IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: Dunque io son (Rossini) | 2:34 |

| with Alberto de Bassini, baritone

Ca. 1898; Bettini cylinder |

||

| 4. | STABAT MATER: Quis est homo (Rossini) | 2:04 |

| with Jane Frankel, contralto

4 December 1900; Seven-inch Victor 554 Take 2 |

||

| 5. | DON GIOVANNI: La ci darem la mano (Mozart) | 2:58 |

| with Emilio de Gogorza, baritone

24 May 1901; Ten-inch Victor 3401 |

||

| 6. | L’ÉTOILE DU NORD: Barcarolle (Meyerbeer) | 2:09 |

| July 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone 9136 Take 3 | ||

| 7. | FAUST: Ah! je ris de me voir [Jewel song] (Gounod) | 2:26 |

| 3 June 1901; Ten-inch Victor 3431 | ||

| 8. | CARMEN: Si tu m’aimes (Bizet) | 2:49 |

| with Emilio de Gogorza, baritone

24 May 1901; Ten-inch Victor 3406 |

||

| 9. | CARMEN: Je dis que rien ne m’épouvante (Bizet) | 2:15 |

| July 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone Q9134 | ||

| 10. | LA TRAVIATA: Ah, fors’ è lui (Verdi) | 2:32 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone Q9208 Take 2 | ||

| 11. | LA TRAVIATA: Addio del passato (Verdi) | 2:16 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone Q9207 Take 2 | ||

| 12. | UN BALLO IN MASCHERA: Ma dall’arido stelo divulso (Verdi) | 2:14 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone Q9199 Take 2 | ||

| 13. | AIDA: O patria mia (Verdi) | 2:01 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone Q9203 Take 2 | ||

| 14. | BOHEMIAN GIRL: I dreamt that I dwelt in marble halls (Balfe) | 3:00 |

| 3 June 1901; Ten-inch Victor 3434 | ||

| 15. | ‘Tis the last rose of summer (Old Irish Air; words by Moore) | 2:18 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone 9200 Take 5 | ||

| 16. | Il Bacio (Arditi) | 2:28 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone 9206 Take 2 | ||

| 17. | La Calasera (Yradier) | 2:21 |

| July 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone T9137 Take 4 | ||

| 18. | Tú [Habanera] (Sánchez de Fuentes; words by Sánchez) | 2:12 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone T9448 | ||

| 19. | Zortzico vizcaíno (Spanish Folk Song) | 2:13 |

| July, 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone T9135 Take 2 | ||

| 20. | Polo (Spanish Folk Song) | 2:30 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone T9457 | ||

| 21. | Fandango (Spanish Folk Song) | 2:23 |

| November 1900; Seven-inch Zonophone T9453 | ||

| 22. | La Borinqueña (Attributed to Ramirez; Puerto Rican National Anthem) | 2:32 |

| 24 May 1901; Ten-inch Victor 3407 | ||

| 23. | Aires criollos (Camora) | 2:41 |

| 3 June 1901; Ten-inch Victor 3428 Take 2 | ||

| 24. | La Partida (Álvarez) | 2:43 |

| 3 June 1901; Ten-inch Victor 3432 | ||

| 25. | Los Ojos Negros (Álvarez) | 3:20 |

| 18 April 1912; (B-11892-1) Ten-inch Victor 63681-A | ||

| 26. | Una Noite (Curros Enríques; Canción Gallega) | 4:28 |

| 9 February 1912; (C-11578) 12-inch Victor 68400-A | ||

| 27. | Lungi dal caro bene (Secchi) | 3:14 |

| 9 February 1912; (B-11581) Ten-inch Victor 63674-A | ||

| 28. | Pietà, signore [Preghiera] (Attributed to Niedermeyer) | 3:30 |

| 5 March 1912; (B-11669) Ten-inch Victor 63674-B | ||

| 29. | CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: Voi lo sapete, o mamma (Mascagni) | 3:29 |

| 18 April 1912; (C-11895-1) 12-inch Victor 68400-B | ||

Accompaniments: Tracks [1-24] accompanied by piano; Tracks [25-29] accompanied by orchestra | ||

Producer: Ward Marston

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston

Audio Assistance: J. Richard Harris

Photographs: Girvice Archer, Gregor Benko, and Roger Gross

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank Gregor Benko, John R. Bolig, Ramona Fassio, Lawrence F. Holdridge, Nicole Rodriguez, Michael Sansoni, and Richard Warren for their help in the production of this CD release.

The following selections are re-recorded from copies in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Laurence C. Witten II in the Yale Collection of Historical Sound Recordings, Yale University Library:

Tracks: [2, 3, 5, 8, 15, 22, 27-28]

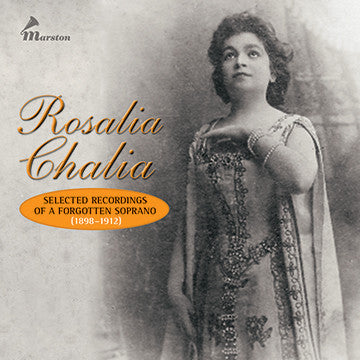

Chalia photos are extremely scarce. Despite efforts to find more photos, Marston has utilized all that could be located.

Rosalia Chalia (1863–1948):

The Forgotten Star of the Phonograph

On 27 December 1942 the Washington Post carried a feature about an unusual phonograph record:

“Ronald Wise … has 12,000 records … one of Wise’s prize records is … dated 1902. The Last Rose of Summer … by one Mme. Rosalia Chalia. … he thought he recognized the voice as that of Adelina Patti, who made a similar recording …in 1905. ... Emilio de Gogorza, who recorded duets with Mme. Chalia under the name Francesco [sic], has denied to Wise that the 1902 record was made by Patti and insists there actually was a Mme. Chalia. Wise, nevertheless, likes to … challenge friends to tell one voice from the other. So far no one has been able to do so.”

Mme. Rosalia Chalia, still alive then, had 48 years earlier received a rave in the same paper (3 June 1894) for her debut in Washington:

“Considerable mystery, as well as interest, has surrounded the little lady who, under the stage name Mme. Chalia, made her appearance in this city as Aida, with the Hinrichs grand opera company. All unknown and unannounced as she was, she made a wonderful hit in this trying role, and Washington hailed her as a worthy singer and one who would someday attain considerable reputation. It was stated that Mme. Chalia was Philadelphia born [sic] and a pupil of Sig. del Puente [sic], but beyond that little could be learned.”

Like other once-celebrated artists, she was forgotten before she died, but she will be remembered as the first great vocalist to make an extensive series of recordings. She lives through them, each one a treasure. Although no one today would confuse her with Patti, Chalia’s records show her extremely flexible voice, its supple timbre, and her huge range. She negotiates coloratura passages with breathtaking agility and beauty. Her old-style coloratura is as good as any you will hear on records, as fleet as Maria Barrientos, Irene Abendroth, Frieda Hempel, or any of the other celebrated songbirds. This is particularly evident on her recording of “Io sono docile” from The Barber of Seville—an amazing tour de force.

Chalia was one of the few singers trained in the old style whose artistry was unimpaired by age at the time of her early recordings. Her impressive technique was obviously rooted in the old school, for she was trained before the new style began to predominate. Conductor and vocal historian Will Crutchfield has observed: “Her combination of extreme virtuosity and sheer reliability was extraordinary even in a time when virtuosity was more common than it later became.” Despite the fact that Chalia specialized in dramatic and verismo roles, she doesn’t sound at all like a modern verismo singer, especially on the earliest records. Comparing how she sounded in 1900 to her 1912 recordings, she seems to be two separate singers. By 1912 her style had become more veristic and there are obvious signs of vocal deterioration, most likely due to overtaxing her voice.

Some mystery remains about her life and career—why her association with major opera houses was desultory and why she didn’t achieve wider international acclaim. Could her misfortune have been merely an accident of timing, appearing as she did in the age of Patti, Melba, and Tetrazzini? Details of her life reveal her to have been difficult, but Calvé, Eames, and countless others were even more so. It could not have been solely her art, which is spectacular and stellar, that prevented her from achieving the same renown.

Rosalia Gertrudis de la Concepción Diaz de Herrera y de Fonseca was born into a prominent Havana family on 17 November 1863. She was always known as “Chalia Herrera,” “Chalia” being an affectionate diminutive of “Rosalia.” She grew up in the city of Santiago de Cuba, where 14-year old Adelina Patti had earlier appeared in a company organized by Louis Moreau Gottschalk. By the time she was eight, Chalia was singing operatic arias and classical songs. She could also play the piano with considerable skill and was soon to master violin technique, studying with the violinist, composer, and conductor Laureano Fuentes Matons (1825–1898). In 1877 her father, an admiral in the Cuban navy, was asked to act as official host to General and Mrs. Ulysses S. Grant. On that occasion young Rosalia sang for the recently retired American president and the cream of Cuban society.

It is said that Chalia continued her education at a convent in Cadiz, Spain, and that subsequently she took up singing more seriously, working with “several famous European teachers.” She returned to Cuba and there met an American from Philadelphia, a family friend, at a reception for Prince Henry of Prussia. He abruptly asked her to marry him; she replied, “If my father wishes me to, I will.” Her father did wish her to and she married. She came to New York for further vocal lessons with the Cuban composer and singing teacher Emilio Agramonte (1844–1918) and made her professional debut as Aida in Philadelphia in 1894, a last minute, anonymous replacement for an ailing soprano. She had been recommended by Giuseppe del Puente, the baritone who had sung in the performance of Faust that opened the Metropolitan Opera House, and who had heard Chalia sing a recital of Cuban songs. When after the performance she was besieged by journalists who wanted to know her name, she was perplexed to give her good family name (the theater was not considered the highest calling then for a woman married into society) but recovered by saying, “Call me Chalia, just Chalia.” She apparently liked the stage and that same year she appeared as Aida in New York, then went to Italy as a member of the company of Milan’s Teatro Lirico, where she scored a success in the title role in the premiere of Gellio Coronado’s opera Claudia. Chalia recalled singing Santuzza in Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana several times in 1896, but apparently not at the Lirico, since house records support only her appearances in Claudia.

In Paris, Chalia consulted Jean de Reszke’s teacher, Giovanni Sbriglia (1832–1916), who persuaded Jules Massenet to reserve the leading role in his forthcoming opera, Sapho, for her. But she was “prevailed upon” to return to Philadelphia, apparently through some ruse manufactured by her husband, and the premiere of Sapho was given to Calvé. While not specifically stated, this may well have been the dissolving point of Chalia’s marriage, and she resumed her American career.

In New York she appeared at a Seidl Sunday Concert on 27 September 1896, singing arias from Verdi’s Ballo and Humperdinck’s Hansel und Gretel, Wagner’s “Träume,” and a group of Spanish songs. Much interested in Cuban independence, she organized a Chickering Hall concert to benefit the cause in November. She, Emilio de Gogorza, and others were banished from Cuba for their efforts. Undaunted, she organized another benefit in May 1897, appearing with de Gogorza and Dante del Papa in New York’s Weber Hall.

She joined Colonel Mapleson’s company, singing the role of Maddalena in the United States premiere performances of Giordano’s Andrea Chénier, and was warmly praised by critics in Boston and Philadelphia. She kept up a busy concert schedule: on 15 November 1897 at a reception at New York’s Arion Society honoring the Belgium violinist Eugene Ysäye and French pianist Raoul Pugno, Chalia participated with the two artists in the premiere of Bruno Oscar Klein’s Sonata for Violin, Soprano, and Piano—the first such work ever composed. At the same venue on 13 December, Chalia sang in the American premiere of Massenet’s Le portrait de Manon. On 4 January 1898 she and Alice Verlet gave the American premiere of Mascagni’s Zanetto in New York. That same month in the city, she appeared in what was reported to be the American premiere of Paer’s Il Maestro di Capella.

In 1898 Chalia and de Bassini joined The Royal Italian Opera Company, touring the United States for 35 weeks. The Los Angeles Times reported on 11 September: “ ... the most noteworthy addition [to the company] … is the engagement of … Chalia … the possessor of a wonderful voice. … a thorough artist.” On 12 October 1898 Chalia sang the principal soprano roles in a double bill of Cavalleria and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci with that company at New York’s Casino with de Bassini, but the performance was reviewed unfavorably the next day in the New York Times: “Signora Chalia is a soprano whose voice may have been a good one once, but it is a sadly worn one now, although she is not past her prime. She forces it unmercifully, and that is probably the explanation.”

A few weeks later on 17 December, Chalia made her debut in Cavalleria at the Metropolitan Opera House on a double bill that also featured Gounod’s Philemon et Baucis with Plançon and Salignac. She was not re-engaged though she did sing with the company one more time—the title role in Aida on tour in Philadelphia in 1902. She was paid $50 for the Cavalleria and $100 for the Aida. (At the time, Calvé commanded $1,800 to $2,000 and Eames $1,100 per performance at the Metropolitan.) Later in the 1898–1899 season Chalia toured the United States for 18 weeks with the Damrosch-Ellis Opera Company, alternating leading roles with Melba, de Lussan, and Gadski, in a company that included Olitzka, Van Cauteren, Pandolfini, Van Hoose, and the New York Symphony, under Walter Damrosch and two other conductors, “with chorus, stagehands, mechanicians, stewards, chef, maids, train crew and manager,” according to Chalia.

By 1899, giving out her age as “just a quarter century,” she formed her own opera company, the “Gran Compania de Opera Italiana Empresa Rosalia Chalia.” From 1900 to 1908 she toured Mexico, Venezuela, Cuba, and Puerto Rico with her company. In Caracas the public demanded she sing all the leading roles, so she sang in 26 of 28 presentations, after which President Castro presented her with a diamond necklace. Her repertoire numbered 52 roles, Carmen her most celebrated (“new, unhackneyed, spontaneous, genuine” according to New York’s the World. “… the only Spanish Carmen that the stage has seen. ... ”), with Aida and Santuzza close behind. In 1899 in Mexico she created a sensation singing in Aida, Faust, La bohème, Tosca, and La traviata, the Bohème and Tosca sung in Spanish translations she had made herself. In a dispatch from Mexico on 19 August 1899 the Chicago Daily Tribune reported “ ... Chalia is a beautiful young Cuban. Her success has been so great that the public and press have divided their attention about equally between her triumphs, the Yaqui campaign and the trial of Dreyfus.” On 17 September 1899 the New York Times reported her great popular Mexican success, and that she “ … even, according to one paper, made an impression on President Diaz.”

From 1908 through 1916 she appeared in the United States as well as Central and South America, both with her own company and as a guest artist. One May 1908 engagement in Cleveland ended as a public relations disaster. She was engaged for Aida but refused to rehearse. Giving interviews to the papers, she said she would have gladly done so “as a favor to the companions [colleagues], but to demand me to rehearse what I have sing since I was so high—oh, he [the Cleveland Hippodrome impresario] have the bold spirit!” Also, the role was to be sung in English: “To demand of me that I sing her in English! Nevar -r-r,” exclaimed the lively prima donna to the Cleveland News.

Another Cleveland paper at the time painted a word picture of the diminutive diva: “Five feet two in stature, plump—not too plump—graceful, ardent, with the blackest of hair, the smallest of hands, the daintiest of little feet, and the most wonderful eyes you have ever looked into. Great, glowing, flashing eyes. ... ”

On 28 May 1911 the New York Times reported on her participation in a benefit for the Bide a Wee Home for Friendless Animals. She and David Bispham sang a duet from Rigoletto, and she sang “Fuggi Traditor” from Don Giovanni and “Il Bacio” by Arditi. The New York Tribune (23 April 1913) reported on a New York folksong recital: “The rapidity with which Mme. Chalia got out of one costume into another, with correspondingly quick changes of scenery, and her vivacity and snap greatly impressed the audience … ” In 1914 she returned to Cuba where she sang a much acclaimed Tosca. On 22 April 1915 she performed in a Carnegie Hall concert, singing arias from Carmen and Cavalleria with piano accompaniment. Indomitable, she then toured Spain and Venezuela. Her final performances were in Cuba in 1916, after which she married her second husband, Pedro Ulloa, in Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania. The two lived in the Harlem section of Manhattan at 350 Cathedral Parkway, where in 1917 she started a teaching studio. In 1925 she began appearing weekly in a ten-minute program of song on New York radio station WEAF; some writers have incorrectly claimed these radio concerts were connected to the Metropolitan Opera.

In addition to teaching, Chalia continued to sing regularly in a series of veladas—weekly musicales—which she began in 1913. She presented some singers in her studio even before they appeared at the Metropolitan Opera, including José Mardones, Andrés de Segurola, and Rafaelo Diaz. In 1940 she founded the Chalia Opera Company, which presented the durable double-bill of Cavalleria and Pagliacci on 28 December that year at New York’s Community Theatre. As recently as March 1943, at one of her last veladas, Chalia gave her celebrated interpretation of Santuzza in a complete performance of Cavalleria, singing (then at the age of 79) with “astonishing intensity in the true Latin style.”

During her last years in New York, record collectors recounted stories of visiting her, living with her husband in less than ideal circumstances. A number of her records were strung through the center holes on a clothesline in the kitchen, a reminder of her work from almost a half century earlier. Then, in March and April 1945, she was rediscovered in her own country, where long, illustrated articles about her appeared in the Cuban papers. On 15 March 1945, a meeting was held in Cuba that included the legendary record collector Dr. Frank Garcia Montes, and possibilities were discussed about ways to honor her; a bill was introduced into the Cuban senate and she was offered inducements to return to Cuba, including a small pension to make her final years more comfortable. She and her husband arrived in Havana for good on 5 August 1946, an emotion-laden occasion for everyone. The Municipal Band directed by Gonzalo Roig accompanied her as she sang the beloved Cuban song “Tú,” after which she announced, “I am in Cuba where I will die.” She was awarded the Order of Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. On 16 November 1948, one day before her 85th birthday, she died there.

Chalia was a true recording pioneer. Between 1897 and 1899 she recorded 116 Bettini cylinders, including duets with her colleagues, baritone Alberto de Bassini and tenor Dante del Papa. Only five or six of these cylinders are known to have survived; here we offer “Dunque io son” from The Barber of Seville with de Bassini. Although the voices are submerged in surface noise, one can readily hear their splendid display of agilitá.

In 1900/1901 Chalia recorded for both the Zonophone and the Eldridge Johnson Improved/Victor Monarch labels: 44 issued seven- and nine-inch Zonophones, 38 seven- and ten-inch Victors, with much duplication of repertoire. Examples of about two-thirds of these recordings have surfaced, usually appearing in less than good condition. She was often partnered on disc by baritone Emilio de Gogorza, and we have included several of their delightful duets. Chalia made 19 additional sides for Victor in 1912, intended for the Latin-American market. Notable among these is her only extant recording of “Voi lo sapete” from Cavalleria, which concludes this CD. Shortly thereafter she made 11 sides of Spanish songs for American Columbia, her farewell to the phonograph. These late Victor and Columbia recordings are even rarer than her 1900 and 1901 discs.

In the months just before returning to Cuba, she wrote some letters to James Fassett, which survive. Her 17 January 1945 letter describes some of her recording memories: “While I do not, like Mr. De Gogorza, recall anyone at Zonophone by the name of ‘English,’ I do very well remember that a Mr. Mitchell was in constant collaboration there with Bettini. And referring now, to some business correspondence, I find here a Victor letter of Jan. 13, 1912 which advised of their preparation for recording 20 selections (the 63,000 series, and 68,400) and in which its writer, D. F. Mitchell, says ‘…No doubt you will remember that when you used to make records for Bettini, he had a manager by the name of D.F. Mitchell.’ I can say positively that some of the recordings were made by Bettini himself—flat, disc records—but I did not know what name they would stamp on them. So I cannot say positively I knew them to be ‘Zonophone’ records, but I believe they could have been none other….To describe Bettini: He was middle-aged; of medium height; black hair; dark complexion, Always going about the laboratory in a dark suit and loose, blue blouse. Always in good humor—the artists were always fond of him. When he used to handle the discs himself he would say: ‘Now just look at this! We are growing!’ He was just like a child, in his enthusiasm.”

James Fassett eventually wrote several articles about Chalia for Hobbies Magazine (now known as Antiques and Collecting Magazine) that appeared in 1945, 1946, and 1949, and we thank the Lightner Publishing Company of Chicago for their cooperation in allowing us to use information from those articles here.

© Gregor Benko and Lawrence F. Holdridge, 2009