CD 1 (62:56) | ||

| 1. | TANNHÄUSER: Dich, teure Halle (Wagner) | 3:40 |

| 11 November 1903; (C-692-1) 85013 | ||

| 2. | DIE WALKÜRE: Ho-jo-to-ho (Wagner) | 2:11 |

| 11 November 1903; (B-693-1) 81018 | ||

| 3. | AÏDA: O patria mia (Verdi) | 3:07 |

| 11 November 1903; (C-694-1) 85012 | ||

| 4. | Du bist die Ruh’ (Schubert) | 3:52 |

| 11 November 1903; (C-696-1) 85025 | ||

| 5. | AÏDA: O patria mia (Verdi) | 3:03 |

| 5 March 1904; (C-694-2) 85012 | ||

| 6. | LOHENGRIN: Einsam in trüben Tagen (Wagner) | 4:03 |

| 5 March 1904; (C-1075-1) 85029 | ||

| 7. | Der Nußbaum (Schumann) | 2:47 |

| 5 March 1904; (B-1076-1) 81024 | ||

| 8. | Aus meinen grossen Schmerzen (Franz) | 2:20 |

| 9. | Liebchen ist da! (Franz) | 0:45 |

| 24 April 1904; (C-1258-1) 85032 | ||

| 10. | Ave Maria (Bach-Gounod) | 2:30 |

| 24 April 1904; (B-1077-2) 81045 | ||

| 11. | LOHENGRIN: Einsam in trüben Tagen (Wagner) | 3:55 |

| 26 November 1906; (C-4061-1) 88038 | ||

| 12. | DIE WALKÜRE: Ho-jo-to-ho (Wagner) | 2:06 |

| 26 November 1906; (B-4062-1) 87002 | ||

| 13. | Ave Maria (Bach-Gounod) | 2:31 |

| 26 November 1906; (C-4063-2) 88039 | ||

| 14. | Erlkönig (Schubert) | 3:36 |

| with Frank La Forge, piano | ||

| 26 November 1906; (C-4064-1) 88040 | ||

| 15. | Verborgene Wunden (La Forge) | 1:25 |

| with La Forge, piano | ||

| 16. | Like the Rose Bud (La Forge) | 1:15 |

| with La Forge, piano | ||

| 26 November 1906; (C-4065-1) 88041 | ||

| 17. | AÏDA: O patria mia (Verdi) | 3:12 |

| 8 December 1906; (C-4128-1) 88042 | ||

| 18. | TANNHÄUSER: Allmächt’ge Jungfrau, hör’ mein Flehen (Wagner) | 3:40 |

| 8 December 1906; (C-4129-2) IRCC-186 (unpublished on Victor) | ||

| 19. | TANNHÄUSER: Dich, teure Halle (Wagner) | 3:34 |

| 17 March 1907; (C-4127-2) 88057 | ||

| 20. | TRISTAN UND ISOLDE: Mild und leise, wie er lächelt (Wagner) | 4:11 |

| 17 March 1907; (C-4319-1) 88058 | ||

| 21. | STABAT MATER: Inflammatus et accensus (Rossini) | 3:48 |

| 17 March 1907; (C-4320-1) 88059 | ||

CD 2 (74:26) | ||

| 1. | Widmung (Schumann) | 2:10 |

| with Frank La Forge, piano | ||

| 14 January 1908; (B-5016-1) 87019 | ||

| 2. | Ständchen (R. Strauss) | 2:27 |

| with Frank La Forge, piano | ||

| 14 January 1908; (B-5017-1) 87016 | ||

| 3. | How much I love you (La Forge) | 1:01 |

| 4. | The Year’s at the Spring (Beach) | 0:52 |

| with Frank La Forge, piano | ||

| 14 January 1908; (B-5018-1) 87026 | ||

| 5. | Ständchen {number 4 from Schwanengesang} (Schubert) | 4:13 |

| with Frank La Forge, piano | ||

| 14 January 1908; (C-5019-1) 88112 | ||

| 6. | Gretchen am Spinnrade (Schubert) | 3:18 |

| with Frank La Forge, piano | ||

| 14 January 1908; (C-5020-1) 88111 | ||

| 7. | AÏDA: Ritorna Vincitor (Verdi) | 4:06 |

| 25 February 1908; (C-5012) 88137 | ||

| 8. | DER FLIEGENDE HOLLÄNDER: Traft ihr das Schiff (Wagner) | 4:33 |

| 26 February 1908; (C-5013-2) 88116 | ||

| 9. | MEISTERSINGER: Selig, wie die Sonne (Wagner) | 3:42 |

| with Marie Mattfied, mezzo-soprano; Ellison Van Hoose, tenor; Marcel Journet, bass and Albert Reiss, tenor | ||

| 29 January 1908; (C-5043-1) 9201 | ||

| 10. | MEISTERSINGER: Selig, wie die Sonne (Wagner) | 3:44 |

| with Marie Mattfied, mezzo-soprano; Ellison Van Hoose, tenor; Marcel Journet, bass and Albert Reiss, tenor | ||

| 29 January 1908; (C-5043-2) unpublished | ||

| 11. | CAVALLERIA RUSTICANA: Voi lo sapete (Mascagni) | 2:53 |

| 26 February 1908; (C-5096-1) 88136 | ||

| 12. | Irish Folk Song (Foote) | 4:00 |

| 26 February 1908; (C-5097-1) 88117 | ||

| 13. | DIE VERKAUFTE BRAUT: Ich weiss Euch einen lieben Schatz (Smetana) | 3:50 |

| with Albert Reiss, tenor; piano accompaniment | ||

| 30 April 1909; (C-7025-1) IRCC 140 (unpublished on Victor) | ||

| 14. | DIE WALKÜRE: War es so schmählich? (Wagner) | 3:36 |

| 30 April 1909; (C-7026-1) 88183 | ||

| 15. | DIE WALKÜRE: Fort denn eile (Wagner) | 2:12 |

| 30 April 1909; (B-7027-1) unpublished | ||

| 16. | TRISTAN UND ISOLDE: Dein Werk (Wagner) | 3:25 |

| 30 April 1909; (C-7028-1) 88165 | ||

| 17. | SALOME: Jochanaan, ich bin verliebt (Strauss) | 1:34 |

| 30 April 1909; (B-7029-1) 81089 | ||

| 18. | GÖTTERDÄMMERUNG: Fliegt heim, ihr Raben (Wagner) | 2:45 |

| 1 May 1909; (C-7030-1) 88185 | ||

| 19. | SIEGFRIED: Ewig war ich (Wagner) | 3:32 |

| 1 May 1909; (C-7031-1) 88186 | ||

| 20. | AÏDA: Fu la sorte ... Alla pompa (Verdi) | 6:42 |

| with Louise Homer, contralto | ||

| 1 May 1909; (C-7033-1) 88163 1 May 1909; (C-7034-2) 88164 | ||

| 21. | AÏDA: La fatal pietra ... O terra addio (Verdi) | 8:22 |

| with Enrico Caruso, tenor | ||

| 7 November 1909; (C-8353-1) 89028 6 November 1909; (C-8348-2) 89029 | ||

CD 1: All recordings made by the Victor Talking Machine Company | ||

Tracks 1-10 with piano accompaniment | ||

Tracks 11-21 accompanied by the Victor Orchestra unless otherwise noted | ||

Languages: German [1-2, 4, 6-9, 11-12, 14-15, 18-20]; Italian [3, 5, 17]; | ||

Latin [10, 13, 21] and English [16] | ||

CD 2: All recordings made by the Victor Talking Machine Company | ||

Accompanied by the Victor Orchestra unless otherwise noted | ||

Languages: German [1-2, 5-6, 8-10, 13-19]; English [3-4, 12] and Italian [7, 11, 20-23] | ||

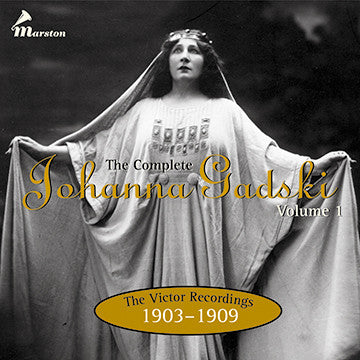

Where have they gone...those dramatic sopranos with brilliant flexible voices, cushioned with velvet, who could sing anything from Wagner to Mozart? With voices that flowed like syrup and power to spare, their singing filled the world's great opera houses at the turn of the century.

To set the stage, the legendary Lilli Lehmann made her last appearance at the Metropolitan Opera in April 1899. In 1900, Lillian Nordica was a dominant presence at the Met, and the remarkable Emma Eames had begun to assume more dramatic roles. The astonishing versatility of these singers is shown by the fact that in the 1900-01 season Nordica sang everything from the three Brünnhildes and Isolde to Violetta and Donna Anna. Eames opened the season as Juliette, but soon was singing Sieglinde in Die Walküre and Elsa in Lohengrin in addition to her first performances as Aïda and Pamina in Mozart's Die Zauberflöte. But even in such company, the newcomer Johanna Gadski more than held her own.

Johanna Gadski was born in Anklam, Prussia in 1872, and studied singing with Mme. Schröder-Chaloupha in Stettin. In 1889, at the age of 17, she made her debut at the Kroll Theatre in Berlin as Agathe in Der Freischütz. She gained valuable experience singing in provincial German opera houses, returning to the Kroll in 1892. In 1895 she began to expand her career internationally, touring Holland and the United States. She sang with the Damrosch Opera Company in 1895-96, creating the role of Hester Prynne in Walter Damrosch's opera, The Scarlet Letter. Further appearances with Damrosch took place in 1898-99. She made her debut at Covent Garden in 1899 as Elizabeth in Tannhäuser, and later that year sang Eva in Der Meistersinger at Bayreuth.

The 27 year-old Johanna Gadski made her Metropolitan Opera debut in a Philadelphia performance of Tannhäuser, on 28 December 1899, substituting for Milka Ternina as Elizabeth. Within two weeks, Gadski made her official Met debut in New York on 6 January 1900 as Senta in Der Fliegende Holländer, soon adding the roles of Sieglinde and Eva. During the next two years at the Met, Gadski added roles from the Italian repertory singing Aïda, Donna Elvira (Don Giovanni), Santuzza (Cavalleria Rusticana), Valentine (Les Huguenots) and Amelia (Ballo in Maschera) demonstrating versatility equaling that of Nordica and Eames.

In 1904 Gadski left the Met for two seasons, giving extensive concert tours in the United States during 1905 and 1906. It was during this period that she studied the role of Isolde with Lilli Lehmann. She performed at the Salzburg Festival as Donna Elvira in 1906 (and later in 1910) with Lilli Lehmann as Donna Anna. She also sang Pamina in 1910, Lehmann performing as the First Lady. Upon her return to the Metropolitan Opera, she sang her first Isolde on 15 February 1907. In addition to the standard repertoire, Gadski sang in premieres of Dame Ethel Smyth's Der Wald in 1903 (the first opera by a woman to be performed at the Met), Ludwig's Thuille's Lobetanz in 1911 and Leo Blech's Versiegelt in 1912. Gadski's career at the Met lasted until 1917, but ended in a great deal of controversy.

Her husband, Captain Hans Tauscher, a former German Army officer, was the North American representative for Krupp, the munitions manufacturer. He had been charged with treason in 1916 by Canada, but was acquitted. When America entered the war, rumors were circulated about Gadski and other German singers at the Met, and they soon returned to Europe. From 13 April 1917, the date of Gadski's last performance at the Met (as Isolde) to 28 November 1921, no performances there were sung in German. The few Wagnerian operas performed, beginning in 1920, were sung in English.

Johanna Gadski returned to the United States in 1926, under the auspices of Sol Hurok, for a series of Wagnerian concerts. Her success led Hurok to organize a German Opera Company to support Gadski in performances of Wagner's Ring cycle. They toured ten cities, including Philadelphia and Chicago. In 1928, Hurok once again formed a company starring Gadski, and expanded the repertory. The tours took place from 1928 to 1930. Gadski formed her own company and appeared in 1930-31. She planned to return to the United States for yet another tour in 1932, but died early that year in an automobile accident.

Even a cursory glance reveals that Johanna Gadski was a major operatic figure. Her career was international in scope, but was focused in the United States during the first quarter of the century. She was neither a flamboyant personality nor a great beauty. At the Met this was in contrast to the charismatic Olive Fremstad and Emmy Destinn, who followed Nordica and Eames, not to mention the glamorous Geraldine Farrar. But Johanna Gadski was held in great esteem in an era that is revered today, and little of the awe that surrounds other singers of that period has extended to Gadski. She was overshadowed in her own time and is now lost in history. But when planning his upcoming season at the Metropolitan in 1907, Gustav Mahler wrote of his need of Gadski for productions of Mozart and Wagner. Listening to Gadski's recordings today, we can readily understand why Mahler needed her.

Johanna Gadski made almost 100 records for the Victor Talking Machine Company during her years with the Metropolitan Opera beginning in November 1903. Her first group reflected her versatility as she sang arias from Die Walküre, Aïda, and Tannhäuser, as well as a group of lieder. The same pattern was followed throughout her recording career. Her selections were often highly original; excerpts from rarely recorded operas, oratorios and songs alternated with scenes from Wagner. She seldom attempted to please popular taste, but unlikely as it seems, she did record "Irish Folk Song," "Annie Laurie," and "Kathleen Mavourneen." But Gadski rarely wandered far from the "heroic."

The first set of Victors included a lyrical performance of "O patria mia" from Aïda. The 2nd take reveals Gadski using her voice with great skill to produce a smooth legato, a brilliant high C, as well as several haunting pianissimos at the end. Notwithstanding the piano accompaniment and a substantial cut in the middle, this is an exceptional early performance of the aria. She recorded the aria again in 1906 with orchestra. This time Gadski's legato is not as smooth as the performance falls short of the magical 1904 version. Gadski's ability to float sustained notes in her upper register is unusual in such a huge instrument and gives her singing a dimension that few other dramatic sopranos have possessed. This ability helped her make the transition from Wagner to Verdi or Mozart. For sheer vocal excitement the 1906 "Inflammatus et accensus" from Rossini's Stabat Mater should be noted. Gadski competes with the trumpets as she sings brilliantly, concluding with several sustained high Cs.

Johanna Gadski's 1907 recording of "Senta's ballad" from Der Fliegende Holländer is remarkable. She had the ability to shift moods, first communicating the movement of the sea with full-voiced agitation, and then in dreamy contemplation, her beautiful voice shimmers as she softly narrates the Dutchman's story. Declaring herself his savior, she again bursts out with Brünnhilde-like force at the aria's conclusion. Her 1906 recording of "Einsam in trüben Tagen" [Elizabeth's prayer] from Lohengrin is also on a sublime level. Gadski's ability to sustain the long drawn-out phrases without a loss of intensity points both to her deep understanding of Wagner's heroine and to her technical ability as a singer. Using both marcato to stress the importance of certain words and portamento to smooth the legato, she gives the prayer a rare significance.

Johanna Gadski is superb in her 1909 recording of "Dein Werk? O tör'ge Magd" from Tristan und Isolde. Sometimes a scene such as this, rather than a familiar aria, gives a better sense of an artist's interpretive skills. Isolde's anxiety is sharply delineated as she impatiently waits for Tristan. Her urgency is expressed in every passionate phrase as Gadski pours out her great resonant tones. This is a model of Wagnerian declamation. Even without a full orchestra Gadski brings the drama vividly to life. One must remember that she was trained for this role by Lilli Lehmann, who grew up with Wagner as a family friend and sang at the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876.

Johanna Gadski concertized throughout the world and made numerous recordings of German lieder. Her voice often sounds heavy in these songs, unable to breathe life into them. The 1903 "Du bist di Ruh' " drags and Gadski seems to wander off pitch at the peak of the ascending line. She was more successful in 1908 when she recorded Schubert's "Gretchen am Spinnrade;" remaining intensely focused throughout the song, building up tension and then shifting the dynamics and gently concluding. I especially like Gadski's recording of Mrs. H. H. A. Beach's setting of Robert Browning's famous poem, "The Year's at the Spring" [Pippa's Song]. It is wonderful to hear a song that might be thought of as slight, treated so monumentally.

Perhaps that is the key to Gadski. She was a monumental singer, always choosing the "grand manner." Her education had evolved at a time when Wagnerian opera was thought of as "the music of the future." Eduard Hanslick (1825-1904) had written in 1879 that "The last remnant of beautiful singing in Germany will be destroyed by Wagner's Ring." For a singer trained in Germany during that period, Gadski was remarkably Italianate. Her voice was smoothly produced with a velvety timbre. She had a brilliant upper register, full and ringing, unlike many heroic sopranos who tend to squeeze or become shrill. Her interpretations, especially of Wagner, are often inspired. When she returned to New York in 1926, W. J. Henderson (1855-1937) wrote that she had become "almost a legend". Like an endangered species, recordings of singers like Johanna Gadski should be closely studied and finally, treasured.

© Harold Bruder, 1997