| Pathé Opera Series Volume 7 | |

Victor Massé

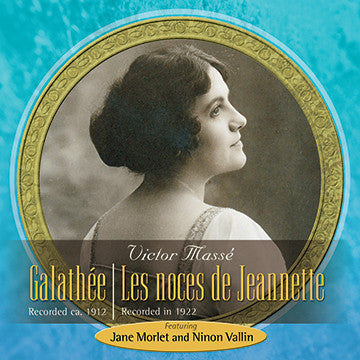

GalathéeOpéra-comique in two actsLibretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré Recorded by Pathé, ca. 1912 Issued on 15 35cm etched-label discs (Galathée 1/30) Later issued on 29cm paper-label discs 1572/1586

| |

| Pygmalion | André Gresse |

| Midas | Alex Jouvin |

| Ganymède | Albert Vaguet |

| Galathée | Jane Morlet |

| |

| Orchestra and chorus of the Opéra-Comique, Paris Conducted by Émile Archainbaud | |

Producer: John Humbley

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston

Audio Assistance: J. Richard Harris

Booklet Notes: John Humbley

Biographies: Luc Bourrousse and John Humbley

Photographs: Girvice Archer, Luc Bourrousse, Roger Gross, and Charles Mintzer

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank Luc Bourrousse, Rudi van den Bulck, Ramona Fasio, Lawrence Holdridge, Peter Lack, and Andreas Schmauder (A complete libretto of this opera is available on each CD as translated by John Humbley and Luc Bourrousse, with editorial and technical assistance by Emily Hauze.)

CD 1 (76:43) | ||

Galathée | ||

| 1. | Overture | 4:41 |

ACT I | ||

| 2. | L’aurore, en souriant chorus | 2:08 |

| 3. | Allez, allez, mes chers amis Ganymède | 1:03 |

| 4. | Hein! Je crois qu’on frappe à la porte! spoken by Midas and Ganymède | 1:30 |

| 5. | Depuis vingt ans j’exerce Midas | 2:22 |

| 6. | Je vous en fais mon compliment spoken by Midas and Ganymède | 2:27 |

| 7. | Qu’ai-je vu? Pygmalion, Midas, and Ganymède | 2:40 |

| 8. | Plus qu’un mot! Midas, Ganymède, and Pygmalion | 1:23 |

| 9. | Toutes les femmes Pygmalion, Midas, and Ganymède | 3:43 |

| 10. | Par Vénus! Au feu qui brillait dans ses regards spoken by Pygmalion | 0:31 |

| 11. | Tristes amours! Folle chimère! ... O Vénus Pygmalion | 7:18 |

| 12. | O ciel! Que vois-je! Pygmalion | 2:20 |

| 13. | Moi! Je suis … je vois … je pense Galathée and Pygmalion | 2:41 |

| 14. | Aimons! Il faut aimer … tout aime! Galathée and Pygmalion | 8:35 |

| 15. | Quels sont ces objets qui m’environnent! spoken by Galathée and Pygmalion | 2:55 |

| 16. | La voilà parti! … Que dis-tu? … Mais quels transports nouveaux? Galathée | 8:40 |

| 17. | Entr’acte | 3:39 |

ACT II | ||

| 18. | Est-ce que mon maître ne m’a pas appelé, il y a un quart d’heure? spoken by Ganymède | 0:27 |

| 19. | Ah! Qu’il est doux de ne rien faire Ganymède | 6:10 |

| 20. | Eh! Mais, que vois-je-là-bas? spoken by Ganymède, Galathée, and Midas | 3:54 |

| 21. | Il me semblait n’être point laid! Midas, Galathée, and Ganymède | 5:05 |

| 22. | Me voilà bien avancé! spoken by Midas, Galathée, and Ganymède | 0:42 |

| 23. | Me voici! … Ah, c’est vous? spoken by Pygmalion, Galathée, Midas, and Ganymède | 1:51 |

CD 2 (75:56) | ||

Galathée, Act II continued | ||

| 1. | Allons, à table! Qu’un vin potable Pygmalion, Midas, Ganymède, and Galathée | 2:55 |

| 2. | Sa couleur est blonde et vermeille [Air de la coupe] Galathée, Pygmalion, Ganymède, and Midas | 5:20 |

| 3. | Assez, ne buvez plus de vin! Pygmalion, Midas, Ganymède, and Galathée | 1:41 |

| 4. | Ah! Misérable! Tu ne m’échapperas pas, cette fois! spoken by Pygmalion, Midas, and Ganymède | 0:40 |

| 5. | Ah! Ah! Ah! Cette maudite statue a juré de leur faire tourner la tête spoken by Ganymède | 0:45 |

| 6. | Ganymède? Hein? Ganymède, c’est moi! spoken by Galathée and Ganymède | 0:43 |

| 7. | Ganymède, c’est toi que j’aime! Galathée and Ganymède | 3:46 |

| 8. | Grands dieux! Pygmalion, Midas, Ganymède, and Galathée | 5:30 |

Victor Massé

Les noces de JeannetteOpéra-comique in two actsLibretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré Recorded by Pathé, 1922 Issued on 10 29cm paper-label discs 1708/1717

| |

| Jeannette | Ninon Vallin |

| Jean | Léon Ponzio |

| Thomas | M. Laurent |

| Pierre | Mme. du Busson |

| |

| Orchestra and chorus of the Opéra-Comique, Paris Conducted by Laurent Halet | |

Producer: John Humbley

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston

Audio Assistance: J. Richard Harris

Booklet Notes: John Humbley

Biographies: Luc Bourrousse and John Humbley

Photographs: Girvice Archer, Luc Bourrousse, Roger Gross, and Charles Mintzer

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to thank Luc Bourrousse, Rudi van den Bulck, Ramona Fasio, Lawrence Holdridge, and Peter Lack (A complete libretto of this opera is available on each CD as translated by John Humbley and Luc Bourrousse, with editorial and technical assistance by Emily Hauze.)

CD 2 (75:56) continued | ||

Les noces de Jeannette | ||

| 9. | Overture | 5:48 |

ACT I | ||

| 10. | Eh ben, je l’ai échappé belle! spoken by Jean | 0:31 |

| 11. | Enfin me voilà seul, et me voilà chez moi! Jean | 5:37 |

| 12. | Eh! Jean … Quoi? Que est-ce qui m’appelle? spoken by Thomas and Jean | 0:22 |

| 13. | Ah! Ma foi, tant pis! … je vais m’amuser spoken by Jean, Jeannette, and Thomas | 5:13 |

| 14. | Parmi tant d’amoureux empressés à me plaire Jeannette | 3:56 |

| 15. | Mais qu’entends-je! Pourquoi ces rires et ces cris! Jeannette | 0:30 |

| 16. | Margot, Margot, lève ton sabot! Jean and chorus | 1:03 |

| 17. | Quoi! C’est moi que l’on raille, et c’est Margot qu’on fête! Jeannette | 1:45 |

| 18. | Oui, ma petite Rose, oui, ma chère Margot! spoken by Jean | 0:58 |

| 19. | Halte-là, s’il vous plaît! Jeannette and Jean | 6:36 |

| 20. | N’allez pas croire, au moins, que ce sont les pistolets de votre père qui me font peur! Spoken by Jean and Jeannette | 1:46 |

| 21. | Ah! Il veut rire avec les autres … Ah! Ça lui est égal spoken by Jeannette | 0:35 |

| 22. | Tenez, le voilà, votre cousin! spoken by Jean, Pierre, and Jeannette | 1:37 |

| 23. | Ah! Vous ne savez pas, ma chère Jean and Jeannette | 1:52 |

| 24. | Cours, mon aiguille, dans la laine [Romance de l’aiguille] Jeannette | 5:08 |

| 25. | Les voilà, ces meubles joyeux [Air des meubles] Jeannette | 3:05 |

| 26. | Ah, que c’est joli, maintenant! spoken by Jeannette and Pierre | 0:38 |

| 27. | Ah! ... il paraît que j’ai dormi! spoken by Jean | 0:39 |

| 28. | Au bord du chemin [Air du rossignol] Jeannette and Jean | 6:58 |

CD 3 (77:10) | ||

Les noces de Jeannette, Act I continued | ||

| 1. | Pourquoi chantez-vous? Je n’aime pas qu’on chante chez moi! spoken by Jean and Jeannette | 0:51 |

| 2. | Allons, je veux qu’on s’assoie Jean and Jeannette | 2:37 |

| 3. | Eh! Dites donc, vous autres! spoken by Thomas, Jeannette, and Jean | 0:34 |

| 4. | Oui, mes amis, c’est ma femme! Jean, Jeannette, and chorus | 4:07 |

Appendix | ||

Galathée | ||

| 5. | Tristes amours! | 2:42 |

| Marie Charbonnel (con) as Pygmalion; ca. 1910; TRIANON (7411) 7411 | ||

| 6. | O Vénus | 3:26 |

| Suzanne Brohly (ms) as Pygmalion; 8 February 1922; GRAMOPHONE (CE238-1) 033225 | ||

| 7. | Aimons! Il faut aimer | 7:57 |

| Rose Heilbronner (so) as Galathée and Joachim Cerdan (bs) as Pygmalion; 17 December 1912; GRAMOPHONE | ||

| 8. | Ah! Qu’il est doux de ne rien faire | 2:56 |

| Georges Régis (te) as Ganymède; 27 December 1910; GRAMOPHONE (16197u) 4-32224 | ||

| 9. | Mais quels transports nouveaux? | 3:14 |

| Lise Landouzy (so) as Galathée; ca. 1911; ODÉON (XP5527) X56227 | ||

| 10. | Ah! Qu’il est doux de ne rien faire | 2:56 |

| Georges Régis (te) as Ganymède; 27 December 1910; GRAMOPHONE (16197u) 4-32224 | ||

| 11. | Enfin me voilà seul | 7:24 |

| André Baugé (ba) as Jean; 19 May 1921; GRAMOPHONE (03446v/03447v) W411 | ||

Les noces de Jeannette | ||

| 12. | Enfin me voilà seul | 2:30 |

| Gabriel Soulacroix (ba) as Jean; July 1900; GRAMOPHONE (1020G) 32879 | ||

| 13. | Enfin me voilà seul | 7:24 |

| André Baugé (ba) as Jean; 19 May 1921; GRAMOPHONE (03446v/03447v) W411 | ||

| 14. | Parmi tant d’amoureux | 2:16 |

| Lise Landouzy (so) as Jeannette; ca. 1905; PHRYNIS 2-MINUTE CYLINDER (10401) | ||

| 15. | Margot, Margot, lève ton sabot | 1:44 |

| Alexis Ghasne (ba) as Jean; 1907; APGA (1736) 1736 | ||

| 16. | Halte-là, s’il vous plaît! | 6:39 |

| Yvonne Brothier (so) as Jeannette and André Baugé (ba) as Jean; 24 May 1921; GRAMOPHONE (03451v/0345 | ||

| 17. | Ah! Vous ne savez pas, ma chère | 2:20 |

| Berthe César (so) as Jeanette and Louis Dupouy (ba) as Jean; 5 September 1912; GRAMOPHONE (17306u) 3 | ||

| 18. | Cours, mon aiguille, dans la laine [Romance de l’aiguille] | 3:05 |

| Jeanne Daffetye (so) as Jeannette; June 1907; GRAMOPHONE (6759o) 33820 | ||

| 19. | Au bord du chemin [Air du rossignol, part 1 only] | 2:58 |

| Jeanne Leclerc (so) as Jeannette; 1905; ODÉON (XP1623) 36126 | ||

| 20. | Au bord du chemin ... Pour entendre mieux [Air du rossignol] | 6:50 |

| Georgette Bréjean-Silver (so) as Jeannette; ca. 1907; ODÉON (XP3267/3268) X56071/56073 | ||

| 21. | Allons, je veux qu’on s’assoie | 4:20 |

| Nelly Martyl (so) as Jeannette and Louis Dupouy (ba) as Jean; 23 November 1911; GRAMOPHONE (02228v) | ||

Victor Massé

1822–1884

Born Félix-Marie Massé, in Lorient, he studied composition with Fromenthal Halévy and was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome in 1844. His first opera, La chanteuse voilée, was given at the Opéra-Comique, and dealt with the story of Diego Velázquez’s servant, who would go to the main square of Seville wearing a veil to sing for money to help the impoverished painter. Massé’s first real success was Galathée, premiered at the Opéra-Comique in 1852, followed a year later by the acclaimed Les noces de Jeannette, and by Les saisons in 1855. The next year saw the premiere of La reine topaze at the original Théâtre-Lyrique under the direction of Léon Carvalho. La mule de Pedro (1863) was well received and continued to be performed throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Paul et Virginie had an even greater success. Premiered at the Théâtre-Lyrique on 15 November 1876, it benefited from a star-studded cast including Victor Capoul, Cécile Ritter (whose daughter, Gabrielle Ritter-Ciampi, would become a great soprano of the 1920s), Jacques Bouhy, Speranza Engally, and Léon Melchissédec. Paul et Virginie, which reached one hundred performances in less than a year, was also given in Brussels (1877), London (1878), New York (1879), Vienna (1880), and Buenos Aires (1881). In 1908 it was revived at the Gaîté-Lyrique with David Devriès and Angèle Pornot. Adolphe Jullien, in an 1894 article for Musiciens d’aujourd’hui, regarded Victor Massé as a successor to Grétry, in as much as he strove, especially in his first works, to marry the music to the text, with the notable exceptions of the bravura arias in Galathée, Les noces de Jeannette, and La reine Topaze.

Massé was appointed choirmaster of the Paris Opera in 1860, and taught at the Paris Conservatory from 1866 until 1876 when he suffered a paralytic stroke. He died in 1884.

• • •

Galathée

Performance history

Galathée was the first of Victor Massé’s great successes. Premiered on 14 April 1852 at Paris’s Opéra-Comique, it propelled him to the rank of one of the most successful composers of his day. In casting the opera, Massé despaired of finding a suitable baritone for the male lead of Pygmalion. Emile Perrin, director of the Comique from 1848 to 1857, always in search of something novel, suggested that Massé use a female singer for the role. Taking his suggestion, Massé gave the part to Palmyre Wertheimber, whose wondrously sonorous and almost masculine voice had already been celebrated by the music-loving poet Théophile Gautier. In addition to Mlle. Wertheimber in the trouser role, there was Delphine Ugalde as Galathée. Not only was she a seasoned singer who could star in such a role (she had already distinguished herself in the creation of Thomas’s Le songe d’une nuit d’été and La dame de pique), she evidently took pleasure in the crânerie (cheekiness) and désinvolture (innocent insolence) that the role of Galathée required. The transvestite convention was unpopular in late nineteenth-century France, though exceptions were made for pageboys and the role of Orphée. Thus Jean-Baptiste Faure took over the role of Pygmalion in the year of its creation, and thereafter it was usually assumed by baritones, such as Jacques Bouhy and Emile-Alexandre Taskin. There were, however, two notable exceptions in the nineteenth century. One was Speranza Engally who interpreted Pygmalion in 1873 at the Opéra-Comique, and although she sang well, plumbing a sonorous low F, she met overwhelming competition from the soprano, Adèle Isaac, making her debut as Galathée. The other was Jeanne Deschamps-Jehin, who in 1890 was the first female Pygmalion at Monte Carlo. Otherwise, Pygmalion remained in its masculine preserve until the 1908 Opéra-Comique revival. This featured the young mezzo Susanne Boyer de Lafory as Pygmalion. Although she was praised for her appearance in opera, after having been a concert artist, critics did not feel she had the requisite weight for the role. As Adolphe Julien pointed out, a baritone suits the score better, particularly in the quartet, where a strong deep voice is needed for balance. Angèle Pornot, as Galathée, on the other hand, was found to be ideal. For the last Opéra-Comique revival in 1911, the cross-dressers won the day, and Pygmalion was entrusted to the great Marie Charbonnel. She made a very rare recording of Pygmalion’s aria “Tristes amours!” for the obscure French label Trianon, which is included in the appendix section of this set. The final performance at the Opéra-Comique marked the 457th since its creation.

The anonymous journalist of Liberté (8 July 1873), commenting on the production of Galathée featuring Engally and Isaac, drew some interesting comparisons with Gounod. Massé in writing Galathée, he said, showed elegance of form, novelty in musical effects, and distinction in style, warmth, and passion, which explains why the opera’s popularity had not waned in twenty years, and justified its place among other favorites as La dame blanche, Le domino noir, and Fra Diavolo. In its story from ancient Greece Galathée anticipates Gounod with his classical themes, and indeed could be mistaken for Gounod. Nevertheless, he stated that Massé lacked the boldness to be the great composer that Gounod had become.

Galathée proved to be particularly popular throughout the nineteenth century. In the 1878 revival, Adèle Isaac was obliged to twice encore the “Air de la coupe,” despite the fact, as one blasé critic wrote, that it had been sung so often in Parisian salons every winter that everyone was utterly weary of it. Outside France Galathée achieved considerable success at least in countries where French was spoken. It was first performed at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels on 22 September 1852, with Jean Aujac, Pierre-Adolphe Girardot, and Delphine Ugalde who had created Galathée in Paris. In Ghent its first performance was on 29 August 1852, where it had seventy-one performances, and was regularly presented there until the 1923-1924 season.

Summary

The story of Galathée is of course that of Pygmalion, and marks the fashion for a comic treatment of classical themes, such as Gounod exploited in Philémon et Beaucis, and Offenbach in Orphée aux enfers. The scene opens in Pygmalion’s workshop. Ganymède, Pygmalion’s servant, is emerging from his customary lethargy when Midas calls in, looking for Pygmalion, to buy the statue of Galathée, which is hidden in a niche behind a curtain. Midas is stealing a glance at the statue when Pygmalion comes in. He is about to take Midas to task, when the latter produces a casket of gold, which Pygmalion disdainfully declines. Midas then realizes that what Ganymède told him about Pygmalion being in love with his statue is indeed true. Pygmalion drives him out, and alone, meditates on the sad love (Tristes amours!) which he vows to Galathée. He goes to destroy the statue, but then calls on Venus to give her light and life. And, indeed, Galathée comes to life. Pygmalion declares his love (Aimons! Il faut aimer), to which Galathée replies, bemused, that something has been kindled within her. Galathée finds a mirror and discovers that she is beautiful but bored with Pygmalion. She disappears into the garden.

The second act opens with Ganymède again emerging from his lethargy (Ah! Qu’il est doux de ne rien faire—Air de la paresse), when he spies Galathée in the garden. Galathée finds Ganymède more attractive than Pygmalion, and is giving him a kiss when Midas enters. He is overcome that the statue should have come to life. Galathée for her part is disgusted by the appearance of Midas; Ganymède explains that he is an old man. The old man declares his love, and Galathée mocks him pitilessly. She takes his gold, but continues to laugh at him. Pygmalion returns with food for supper, while Midas and Ganymède hide. Ganymède is summoned, and they prepare to eat (Allons, à table-Quartet), with Midas chiming in from the wings. Galathée takes her first glass of wine (Sa couleur est blonde et vermeille—Air de la coupe), finds it is very much to her taste, and drinks rather too much. She declares she will have her own way, overturns the table, and storms out. Pygmalion, distraught, discovers Midas hiding, though the latter is more concerned about having lost his gold. A little later Ganymède is alone, relaxing of course, when Galathée slinks back and suggests they both run away. As they are leaving, arm in arm, Pygmalion and Midas return. Pygmalion, furious, asks Venus to turn Galathée back into a statue. Miraculously, the curtain over the niche is raised, and the beautiful statue is back there as in the first act. Pygmalion runs off to join his friends, singing the praises of mistresses and ephemeral love.

THE SINGERS

Jane Morlet

Seen from the twenty-first century, Jane Morlet may seem to be a minor artist, but in the Paris of the closing years of the Belle Epoque she was the talk of the town. In the years before World War One, two rival houses were giving the Opéra and the Opéra-Comique considerable competition. The Gaîté-Lyrique consistently put on ambitious operas with most prestigious casts, including such Opéra luminaries as Félia Litvinne and Ernest Van Dijck, and had in 1909 staged the greatest operatic success of the period, Nouguès’s Quo Vadis?. The Théâtre du Trianon-Lyrique, a relative late-comer to the scene, aimed more at the lighter end of the Opéra-Comique’s repertoire, with considerable success. Jane Morlet sprang into prominence on the Paris scene of 1906, when she was chosen as the leading soprano to inaugurate the Trianon-Lyrique’s new management under Félix Lagrange. She was born on 22 January 1879, the daughter of the soprano also named Jane Morlet (born Jeanne-Flore-Eugénie Guillot) and Louis Morlet (1849–1913), a distinguished Opéra-Comique baritone, a celebrated Figaro who created La mascotte and Chabrier’s Une education manquée. Jane Morlet (junior) made her debut at Monte Carlo on 18 March 1906 in the local premier of Bizet’s forgotten opera, Don Procopio. For the first Lagrange season of the Trianon-Lyrique, she sang a large number of light soprano roles in Zampa, Haydée, La muette de Portici, Le caïd, La Juive, Le domino noir, all to critical acclaim. The 1909 season was even more eventful for her as a figure in operatic history. She assumed the title role in the creation of Pons’s Laura (“a heart-rending Laura, a clear, supple soprano voice, which she uses with infinite skill”) and Chloé in Fernand Le Borne’s Daphnis et Chloé “with all the naïve passion that is required,” as Edmond Stoullig attested. 1910 saw the same sort of season at the Trianon-Lyrique, and again Stoullig emphasized the importance of the singers who contributed so much to the success, the first and foremost being Jane Morlet! In 1911 the Trianon-Lyrique put on the French first performance of Zaza, with Morlet in the title role and with her mother as Zaza’s mother, under the pseudonym of Mme. Jyhem (“J. M.”). Stoullig found the opera musically conventional, but could not praise the singers enough, in particular Jane Morlet, “who gave a superior interpretation of Zaza with flame, fire, and extraordinary passion.” Another more ephemeral creation took place on 21 December: L’auberge rouge by Jean Nouguès, with Morlet in the leading role. A noted revival of that season was Delibes’s Le roi l’a dit, in which Morlet interpreted the leading role of Javotte. 1911 saw the production of Massenet’s Don César de Bazan, with Morlet as Maritana. That season, she also portrayed the role of Ernestine in Offenbach’s M. Choufleuri restera chez lui le … , impersonating one of the best known virtuosa stars of old-fashioned Italian opera, Henriette Sontag. On 20 June 1912, Morlet sang Philine in a benefit performance of Mignon with Jeanne Marié de l’Isle in the title role, Maurice Capitaine as Wilhelm, and Louis Azéma as Laërte. In 1913 Morlet starred in Boieldieu’s La dame blanche, Xavier Leroux’s Le chemineau, and in Gounod’s Mireille. Morlet somehow found time to guest in Marseille, where she created the role of Minnie in the first performance in France (and probably also in French) of La fanciulla del West (La fille du far-west) on 8 November 1912 with the composer in attendance. By 1916 Morlet was announced as a dramatic soprano, and sang Mathilde in Marseille’s ever-popular Guillaume Tell. Wartime conditions soon made it impossible to continue operatic production at the Trianon-Lyrique, and when operatic life returned to normal at the end of the hostilities, Morlet never seemed to find her mark again. She was heard in operetta, where she increasingly became associated with the roles of charming old ladies, and eventually she gave up singing altogether but continued in similar roles in the spoken theater until 1950. She died in Paris on 22 December 1957, having been married twice, in 1900 and 1927.

Jane Morlet made at least two series of recordings before the First World War, which mirrored the many roles she assumed during the period. Her first records were a few titles for Odéon reflecting her first years at the Trianon-Lyrique, and a little later, Pathé recorded additional extracts representative of her repertoire: Le domino noir, Les diamants de la couronne, Le songe d’une nuit d’été, and another Massé opera, Paul et Virginie. In the years between the wars Morlet was heard in minor roles in the Odéon operetta extracts, including Reynaldo Hahn’s Brummel and Oscar Straus’s Ein Walzertraum (Rêve de valse). As Galathée, a role she interpreted at the Trianon-Lyrique, Morlet proves on record to be the perfect exponent of genuine opéra-comique style. She had not only wide actual experience in the repertoire, but also the ideal training for it, since her father was a pupil of Coquelin, and opéra-comique is as much about comedy and words as it is about singing and notes. The vividness of her words is striking and makes her mischievous portrayal very much alive.

André Gresse

The son of the famous bass Léon Gresse (1845–1900), André Gresse was born in Lyon on 23 March 1868. He studied singing with Taskin and Melchissédec at the Paris Conservatory, graduating in 1896. His first stage performance was at the Opéra-Comique in the same year as the Commandeur in Don Juan. He remained there for several seasons, creating roles in Massenet’s Sapho and Erlanger’s Juif polonais, and also sang Gaveston in La dame blanche and Max in Le chalet. In 1901 Gresse went over to the Opéra where his first role was Saint-Bris in Les Huguenots. There, he sang Osmin in the Paris Opera’s first performance of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail (L’enlèvement au Sérail) and became renowned for his portrayals of the major Wagnerian bass roles and the Mephistos of Gounod and Boito. Gresse has also gone down in history as the creator of Sancho Pança in Massenet’s Don Quichotte, which he interpreted alongside Chaliapin at Monte Carlo in 1910, and with Vanni- Marcoux in Paris, sharing the role with Fugère the following year. Gresse was still singing at the Paris Opera until the end of the 1920s. He died in 1934.

André Gresse began his recording career in 1902, making a small number of records for Pathé. That same year, he began his association with the French Gramophone Company, which lasted until 1912.

Albert Vaguet

Albert Vaguet’s career can be divided into two distinct parts: the first as a leading tenor of the Opéra from 1890 to 1902, and from then on until 1928 as the most recorded tenor in France. The experience gained during the first career gave much of the importance to the second. The actual reasons for his early retirement from the stage remain obscure. The first issue of the trade journal Phono-Ciné-Gazette in 1905 announces his comeback to Paris after a long absence, but no explanation is given. Most sources, including Kutsch and Riemens, have cited, as the cause, a leg amputation in 1903. Recently however, record collector Lawrence Holdridge brought to light a 1913 article on Vaguet published in Musical America, in which Vaguet states that his retirement from the stage was due to a tonsillectomy, which affected his vocal cords such that he could sing only for very short periods. This may explain why some of his records show an extremely mellifluous voice, while in others, one can discern extreme vocal strain.

Albert Vaguet was born in Elbeuf in Normandy on 15 June 1865. He studied at the Paris Conservatory, graduating in 1890 and making his debut at the Opéra on 29 October of that year as Faust, the role most closely associated with him, followed by La Trémoille in Paladilhe’s Patrie, and Fernand in Donnizetti’s La favorite. He was also in the cast of the first Paris performance of Chabrier’s Gwendoline in 1893. Over the next twelve years he assumed leading roles, both dramatic and lyric, such as Lohengrin, Don Ottavio, and the Duke in Rigoletto. In 1897 he was chosen to interpret Faust in the Opéra’s first performance of Berlioz’s La damnation de Faust, but apparently there was obvious evidence of vocal discomfort. In 1899 he sang the title role in a noted revival of Méhul’s Joseph. He was also associated with several creations, including Samuel Rousseau’s La cloche du Rhin, from which he later recorded an extract, Chabrier’s Briséis, Le roi de Paris by Georges Huë, and the leading role (Marcomir) in Saint-Saëns’s Les barbares.

Vaguet’s recorded legacy reflects not only his stage career, but also encompasses many of the lighter operas associated with the Opéra-Comique, and even includes a few operetta extracts, most remarkably John Styx’s aria from Offenbach’s Orphée aux enfers, transposed for tenor voice. Ganymède was certainly not among his stage roles, and, nearing 50 years of age, he was an unlikely interpreter of the youthful servant.

Alexandre (Alex) Jouvin

Alex Jouvin was a leading operetta tenor of the period immediately before and after the First World War. He was a stalwart of the Trianon-Lyrique troupe from 1906 until at least the late 1920s. There in 1912 he took part in the creation of the role of Lucas in an operetta by Claude Terrasse, Cartouche, and the Opéra-Comique version of Lehar’s Amour Tzigane. Jouvin was also active as a producer. In 1923 the Trianon-Lyrique had him produce Gluck’s Les pèlerins de la Mecque, in which he also sang the role of Osmin. His only other recording seems to be the role of Champlâtreux in an excellent abridged version of Hervé’s Mam’zelle Nitouche, made for Artiphone around 1930. If slightly over the top, his Midas in this recording of Galathée remains faithful to the opéra-comique buffo tradition.

Emile Archainbaud

The conductor, Emile Archainbaud, was born Marie-Emile Archainbaud in Paris on 24 September 1874, and died in Paris on 14 August 1953. He was the son of singer and teacher Eugène Archainbaud, and was conducting at the Gaîté-Lyrique when this recording was made. He transferred to the Opéra-Comique in 1920, making his debut with a performance of Mireille. He went on to conduct such works as Le jongleur de Notre Dame, and in 1921, the first performance of Marc Delmas’s opera, Camille.

• • •

Les noces de Jeannette

Performance history

Les noces de Jeannette was without doubt Victor Massé’s most popular and enduring composition. It had its first performance at the Opéra-Comique (Salle Favart) on 4 February 1853, with the young star Marie-Caroline Miolan-Carvalho (1827–1895) in the title role. It is a moot point whether it was the soprano who launched the opera or the opera which launched the career of one of the nineteenth-century’s major sopranos, as Jeannette was one of her early triumphs.

Whatever the explanation for the success, Les noces de Jeannette was off to an excellent start and clocked one hundred performances at the Opéra-Comique in little over a year, reaching its thousandth performance there by mid-1895, a splendid affair with Lucien Fugère as Jean and Jeanne Leclerc as Jeannette. There was some slackening in the twentieth century, though each year saw at least some performances until the Second World War. In 1921 it was given a feted 1500 performance, with Marguerite Roger and Maurice Sauvageot, only for it to be later discovered that a mistake had been made, and that it was in fact the Salle Favart’s 1393rd performance. The following year it was put on in a gala performance to celebrate the centenary of Victor Massé’s birth, this time with Jeanne Calas in the title role and André Baugé as Jean. It was performed in 1942 with Odette Turba-Rabier and Emile Rousseau, and then slipped out of the repertoire for eighteen years.

Les noces de Jeannette was the last of Victor Massé’s works to remain in public view if not in the repertoire. It had a noted revival at the Opéra-Comique in 1960, to public satisfaction and critical acclaim. The cast was an excellent one: Liliane Berton and Michel Dens (later replaced by Jean-Christophe Benoît), while the staging by Robert Manuel and the costumes and sets designed by the much-loved cartoonist Raymond Peynet also contributed in no small measure to its success. Critics, who declared they had been dreading the event, actually enjoyed it, and the audiences gave an enthusiastic response with many curtain calls. One journalist, from La vie militaire, declared a little rashly that audiences would still be applauding Les noces de Jeannette in a hundred years, whereas Thiriet’s work La locanderia, given as the other opera on the double bill, would soon be forgotten. Les noces de Jeannette was indeed again heard in the 1966–1967 season, with Liliane Berton again, and Yves Bisson. By the 1970s, television was the dominant medium in France and Les noces was one of the first works presented on Pierre Sabbagh’s television series, “A l’opérette ce soir,” in early 1972, with Mady Mesplé and Jean-Christophe Benoît. Since then, performances have become fewer and fewer: at the end of the twentieth century, it was heard in a production by the Nadia Baji company at the Théâtre Maurice-Ravel, with ten performances between October 1999 and January 2000. It was mounted at the Opéra-Comique in April 2005, with Cassandre Berthon and Marc Barrard and a youth orchestra, but had only one performance.

From the start, critics scoffed at the naive plot inspired by Molière, and the libretto written by the popular librettists Jules Barbier and Michel Carré. It was nevertheless an outstanding success, for reasons which are not hard to understand. Miolan-Carvalho’s brilliant singing at the first performances undoubtedly helped the work off to a good start, and its continued popularity was certainly due to the effective music. No less than four of Jeannette’s airs became tremendously popular in late nineteenth-century France: the brilliant “Nightingale song” of course, but also the melancholy “Parmi tant d’amoureux,” the delicate “Cours, mon aiguille,” and the rollicking “Furniture aria.” Jean’s music is perhaps less striking, though the dissolute invitation to the dance, “Margot, lève ton sabot!” was one of the most recorded French baritone arias of the early years of the gramophone. The duets also give some spirited moments in a tight-knit score, which is not only efficient, it also gives voice to some of the most elemental features of opera in general. Les noces de Jeannette represents an interesting variation on archetypal operatic roles. Bernard Shaw quipped that Verdian opera could be summarized as the struggle for the tenor to make love to the soprano and being thwarted therein by the baritone. Here in Victor Massé’s work, it is the soprano who is the pursuer, whereas the principal male role, here sung by a baritone, is essentially reactive. This female initiative is brought out essentially by the singing: while the audience learns through the dialogues that Jean had originally asked Jeannette to marry him, invited all their friends, and paid the fiddlers, the music presents him as the man who ran away from his wedding, bargained to forestall Jeannette’s father, and lost his nerve when his bluff is called. It is Jeannette’s music that propels the action forward, from the leading role in the duets to the act of wedded piety when she sheds a tear over the torn jacket. Music indeed, and singing in particular, have the last word, as is best exemplified by the “Nightingale song.” It is well known that Gounod inserted the Waltz into Mireille so that Miolan-Carvalho could show off her coloratura, whereas Massé crafted the “Nightingale song” as the centerpiece to the whole opera. Situated pivotally in the middle of the work, Jeannette’s evocation of the nightingale is a not too oblique reference to her own love, and her love is song itself, and what song! As Jean remarks, he did not know that Jeannette could sing like that, and it is indeed her singing as he sleeps, which wins him over and makes him happy to marry her. Singing is love, and in singing love triumphs. What better illustration could there be of the power of song and opera. No wonder that the petits bourgeois of the Third Republic recognized themselves in this outpouring of song.

Summary

The action takes place in a village in nineteenth century France, and the scene is set in the house of Jean (baritone). Jean rushes in and recounts the fiasco of his marriage ceremony. Just as the mayor asked if he would take Jeannette (soprano) as his wife, instead of answering, he took to his heels (Enfin me voilà seul). He concludes that a bachelor’s life is the best choice for him. Thomas comes to tell Jean that his friends are going ahead with a party as planned, and Jean agrees to join them, but is intercepted by Jeannette demanding an explanation. Jean can only mumble that the idea of marriage scares him. Jeannette appears to acquiesce, though she mentions that her father, an old soldier, is furious and busy loading his pistols. Jean goes off to the party, and Jeannette rues her choice of suitor (Parmi tant d’amoureux). Through the window Jeannette spies Jean dancing with Margot, the village harlot (Margot, lève ton sabot!), and vows revenge. Back in the house Jean is confronted by Jeannette threatening paternal intervention (Halte-là, s’il vous plaît!), and begins to take things seriously (Jarnigué, ce n’est pas gai!). Jeannette offers to dissuade her father, if Jean agrees to sign a paper, which he does. This turns out to be the marriage certificate, which Jeannette then refuses to sign in revenge for Jean’s earlier refusal. Jean, however, is quite happy to accept this arrangement, so Jeannette arranges a diversion with her cousin Pierre, and she signs the certificate herself. Jean, now livid, lists all his faults and paints a grim picture of married life (Ah! Vous ne savez pas, ma chère). He storms out to sleep off the wine in the hayloft, while Jeannette sets about mending Jean’s torn wedding jacket, shedding a tear as she stitches (Cours, mon aiguille dans la laine). The peasants then arrive with Jeannette’s furniture to replace Jean’s shabby interior (Les voilà, ces meubles joyeux). Jean wakes and is amazed to find his house transformed, while Jeannette from afar tells of the nightingale, which sings its love every night at her casement window (Au bord du chemin—Nightingale song). Jean is enchanted by Jeannette’s singing and cannot be angry with her, try as he might. When he sees his wedding jacket neatly mended, still moist from Jeannette’s tears, he relents, and orders the bells to be rung, so that the whole village knows how happy he is to be married to Jeannette.

THE SINGERS

Ninon Vallin

Ninon Vallin was without doubt the most completely recorded of all major French singers of the first half of the twentieth century. She was born Eugénie Vallin in Montalieu-Vercieu not far from Lyon on or about 7 September 1886, and died near Lyon on 22 November 1961. She studied music at the Conservatoire in Lyon for three years and continued at the Conservatoire Fémina-Musica with Meyrianne Héglon. Her legacy is enhanced by the fact that her recording career paralleled her appearances on stage and the concert platform. The Record Collector (volume 48, no. 2, 2003) provides a comprehensive discography and much hitherto unknown material on her career, so the remarks here merely draw attention to the close relationship between her stage career and recordings.

Vallin’s debut at the Opéra-Comique in 1912 was as Micaëla in Carmen, whose third act aria she recorded in 1921, and the duet “Parle-moi de ma mere” in 1934 with Miguel Villabella. In 1926, during her second Opéra-Comique period, Vallin appeared more frequently in the title role, subsequently singing it often both in France and abroad. She recorded extensive extracts of Carmen, both solos and duets, mostly electric recordings. Mignon was added to Vallin’s repertoire during her initial Opéra-Comique season, the first of the roles tending towards the mezzo end of the soprano range, which particularly suited her voice. She remained associated with the role of Mignon, and was chosen to sing the feted 1600th performance at the Opéra-Comique in 1927. She recorded two versions of “Connais-tu le pays?”, both duets with Lothario, and “Elle est aimée”, though she never committed the Styrienne to wax. Louise, a role first assumed by Vallin in 1914, played an important part in her stage and recording career. She recorded “Depuis le jour” on six occasions, and sang the title role in Columbia’s 1935 abridged recording of the opera. Mimi in La bohème was also one of Vallin’s major roles, sung in French for the Opéra-Comique performances and in Italian for those in South America. Mimi’s entrance and farewell were recorded in several versions (all in French), and in 1932, Vallin recorded the quartet and extracts from the final scene with Villabella. She twice recorded Musetta’s waltz, though there is no evidence she ever sang the role on stage. Manon, a role she assumed in 1915, was to be even more important for Vallin, as she sang it in France and both North and South America throughout most of her career. Sadly, there is no complete recording, but she did commit to wax all the arias and most of the duets save the finale. Charlotte in Werther, another role midway between soprano and mezzo, fared better, as there is the 1932 complete recording with Georges Thill, as well as many extracts recorded in the years between the wars.

Vallin remained at the Opéra-Comique until disagreement with the manager, Pierre-Barthélemy Gheusi forced her to leave in 1915. She sang extensively in Latin America, then returning to Paris, though this time to the Opéra for her first Thaïs in 1920, quickly adding the two Marguerites (Faust and La damnation de Faust), before her career there came to an abrupt end, followed by another stint in Latin America. Berlioz’s Marguerite is represented by an abbreviated version of the two arias in a recording from the period of her Opéra appearances and in more substantial extracts recorded at the end of her career in 1955. Gounod’s Marguerite is represented by the two famous arias recorded in several versions, and the garden and church scenes recorded in 1930. Vallin’s return to the Opéra-Comique in 1924 featured her as Louise, while the following year, she again sang both Marguerites at the Opéra. She toured France and the world in subsequent years, with concerts taking up more of her activity than opera. Her repertoire of French and Spanish songs are well represented on disc, though there is little of the Debussy with which she was associated at the beginning of her career.

Les noces de Jeannette cannot be counted among Vallin’s major stage roles. She does not seem to have sung the role at the Opéra-Comique, but Alfred de Cock has documented her performances of the role in Montevideo in 1921. A decade later Pathé called on Vallin again, this time with André Baugé who often performed the role of Jean on stage, to record the confrontation scene (Halte-là, s’il vous plaît!) first in 1931 and again in 1934. She is very amusing indeed as Jeannette, displaying talent and individuality more than actual schooling in a given tradition, sounding altogether more modern, a bit like a young Gaby Morlay—quite charming.

Although it was not one of Vallin’s preferred parts, Les noces de Jeannette would seem to fulfill the demands that she made on music before she consented to record it. This is how Robert de Fragny, her authorized biographer, put it in 1963: “Before she consented to consign her voice to the gilded prison of these wax discs, Ninon would demand some free choice of her own when the companies prevailed upon her to record potboilers for publicity reasons. But she set no hard and fast limits to her art, applying it to all musical styles, or at least to those pieces which are genuinely musical, knowing full well that inspiration, like the spirit, blows where it will, and can sometimes be found more delightfully in a snatch from an operetta than in a serious piece by some boring Great Master.”

Léon Ponzio

Léon Ponzio was born in Nice on 10 February 1883 of a well-known local family. He started singing at the Catholic primary school. On leaving school he initially worked in his uncle’s shop, but a career in singing called, and he left in 1907 for Paris where for three years he attended the Conservatory, winning prizes from his very first year. By the time he finished in 1909 he had achieved a considerable reputation as the best Opéra-Comique graduate of his year. He must have been a natural for comic roles, and was already viewed as a worthy successor to Fugère. His Conservatoire “prize songs” were favorably commented on over the years. His Figaro had already been praised, and the scene from Falstaff which he interpreted in the 1909 competition was reviewed in Monde musical: “M. Ponzio seems to be the only singer worthy of the Opéra-Comique first prize, as he is not content merely to interpret the role of Falstaff as the wonderful singer he is, but he totally embodies the role, he lives it with an intelligent precision in his gestures, and shows an interesting talent as an actor.” Comœdia in 1908 had already commended him on his versatility: “with his baryton à Mercure he can sing anything.” One limitation was wryly noted (possibly by Pierre Lalo) when he sang an extract from Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide: he started off with such gusto that the listener could be forgiven for thinking that it was the Agamemnon from La belle Hélène singing, rather than the king of the Gluck opera. These initial evaluations of his voice are strikingly prescient since roles requiring strong characterization and especially comic parts would become his special preserve.

Ponzio made his debut in 1909 at the Gaîté-Lyrique and then sang in French provincial theaters. From 1910 he was a member of the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, where he took part in many local premieres, including Nouguès’s Quo Vadis?. After the First World War he returned to Brussels between 1920 and 1922. From that time on he pursued a career in operetta, singing in Les mousquetaires au couvent at the Théâtre-Lyrique in Paris in 1922. In 1924 he toured Latin America in operetta. Back in Europe he was heard in the title role of Mârouf—a role with which he was increasingly associated—first in Turin at the Teatro Regio in 1925–1926 and then in France. His period of fame really started with his participation in a gala performance of the Barbiere di Siviglia at the Opéra—in Italian, perhaps in deference to the star, Conchita Supervia. There followed a period of seven years during which he was a member of the Paris Opera, singing roles such as the father in La traviata (d’Orbel in the French version), and his beloved Mârouf, though he also took part in performances at the Opéra-Comique as a guest artist. He returned to Belgium in the 1930s, making guest appearances in Ghent in the 1932–1935 season and singing at the Oostende Kursaal in 1930 and 1932. He sang at Covent Garden in 1935, again as Figaro in the Il barbiere, and as Marcello in La bohème, a role also associated with him throughout his career. He continued singing until the Second World War.

His recording career was rather short: apart from his participation in the complete recordings of Manon and Les noces de Jeannette for Pathé, he made over thirty sides for Pathé in the 1920s and early 1930s, with operetta extracts predominating. In the 1930s he made a small number of records for French Columbia and Salabert. His portrayal of Jean on the present set is an excellent example of opéra-comique rondeur and spirit.

Laurent Halet

Laurent Halet, the conductor, does not seem to have performed at the Opéra-Comique: he worked essentially in music halls, being first mentioned in 1889 as conductor at the Paradis Latin; from there he went up the ladder of Parisian houses, working successively at the Concert Européen, Parisiana (where he was Principal Conductor from the opening in 1894 to 1905), Concert Mayol (1910–1912), Folies-Bergère, and the Casino de Paris (Paris qui jazz!, 1920, with Mistinguett and Harry Pilcer), among many others. Much in demand as an arranger of music for revues, he was also very active as a composer of (very) light operettas and fantaisies, churning out an impressive number of them over more than thirty years, including Un Déshabillé à l’octroi, (1896; it turned up the following year in Brussels as Un déshabillé à la douane), Au tonneau des Danaïdes (1897), Le harem de Pontarlier (“maraboulerie in one act,” 1897 as well), Petits trottins (same year, revival Marseille 1910), La princesse des flirts (1906), Le planteur du Connecticut (1908, with Willy Redstone), or Jean-Jean (1924). He left several recordings of light music with his orchestra and died in February 1932.

Singers Featured in the Appendix

Baugé, André [ba] (1893–1966) Born in Toulouse, his mother was the renowned operetta singer Anna Tariol-Baugé and his father was a singer and painter Alphonse Baugé (unknown–1933), a baritone who sang mainly in the French provinces and in Russia. André first trained with his father as a painter, but later studied singing, making his debut in Fécamp. He sang for one season in Grenoble before being called up for military duty in the First World War. He was engaged at the Opéra-Comique in 1917, while recovering from injury, his first role being Frédéric in Lakmé. He became particularly associated with La basoche, Mârouf, and Les noces de Jeannette. He took part in the premier of Fauré’s Masques et bergamasques in 1920, and remained at the Opéra-Comique until 1925, when he was called to the Théâtre Marigny for the French premier of Messager’s Monsieur Beaucaire. From that time on, he would find his niche in operetta. In 1929 he was appointed director of the Trianon-Lyrique, but continued his singing career, appearing later at the Opéra de Marseille, the Théâtre du Châtelet, and Mogador. He also made a number of films and was one of the most prolific recording baritones of his day, first for the Gramophone Company (1920–1923), and well into the 1930s for Pathé. His Gramophone Company discs reflected his Opéra-Comique repertoire, recording duets with colleagues Yvonne Brothier, Suzanne Brohly, Charles Friant, René Lapelletrie, and Eugène de Creus. His Pathé sides are almost all operetta and song titles.

Bréjean-Silver, Georgette [so] (1870–1951) She was born Georgette-Amélie Sixsout. The first part of her name, Bréjean, apparently comes from the maiden name of her mother, the curiously baptized Emile Bregeon. Early in her career Georgette added the name of her first husband and was known as Bréjean-Gravière. She made her debut in 1890 in Bordeaux, coming to the Opéra-Comique in 1894, where she sang in a new production of Manon, her most celebrated role, for which Massenet wrote the Fabliau in place of the Gavotte. When Massenet’s Cendrillon was premiered in 1899, it was Bréjean-Gravière who was chosen to create the Fairy Godmother. Her other roles included Rosine in Barbier de Séville, Angèle in Le domino noir, Philine in Mignon, and Leïla in Les pêcheurs de perles. She sang outside France in Monte Carlo (1895: Manon and Lakmé) and later in Brussels (1903). In 1900, having been widowed the previous year, she married the composer Charles Silver. Her witnesses were Massenet and Albert Carré. She took part in the creation of her husband’s opera La belle au bois dormant, in Marseille (7 January 1902 and again in Brussels, 1903), from which she recorded an extract. Her records were made for Fonotipia and Odéon between 1905 and 1911.

Brohly, Suzanne [ms] (1882–1943) For a quarter of a century, Brohly was one of the mezzo mainstays of the Opéra-Comique. She made her debut in 1906 in the role of La Vougne in Georges’s Miarka and was closely associated with other contemporary roles, participating in a dozen creations, the best known of which include Erlanger’s Aphrodite (1906), Dukas’s Ariane et Barbe-Bleue (1907), Samuel-Rousseau’s Tarass-Boulba (1919), and in particular Lazzari’s La lépreuse (1912), from which she recorded a moving extract. Her visits to the recording studio were frequent, mostly for Gramophone before and after the First World War, then for Pathé in 1924 (six sides), and finally an electric “concise” set of Carmen, one of her best roles, for Polydor around 1930. Suzanne Brohly has been included in this compilation to demonstrate Massé’s original conception of Pygmalion as a mezzo soprano.

Brothier, Yvonne [so] (1889–1967) Brothier was one of the leading “light” sopranos of the Opéra-Comique between the two world wars. Legend has it that she was discovered by Edmond Clément on a train. The tenor was so impressed by the youngster’s voice and musicianship that he invited her to sing with him at the concert he was giving that evening. Her official debut was at La Monnaie in Brussels in 1914, but she soon returned to Paris, where she sang at the Opéra-Comique beginning in 1916. She appeared at other French houses, including the Paris Opera (1931, 1933, and 1936), and was later closely associated with the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin until her retirement in 1939. Like Brohly, she made her name in contemporary works, and took part in many creations: Fauré’s Masques et bergamasques (1920), Lazzari’s Le sauteriot (1920), Samuel-Rousseau’s Le hulla (1923), and most notably Bruneau’s last opera, Virginie (1931). She was also particularly appreciated in concert and recitals and was chosen to make the first broadcast in France in 1921, when she sang the “Marseillaise” on the radio. Her recordings, entirely for Gramophone, acoustic and electric, are numerous and contain a generous proportion of the contemporary music with which she was associated. Not all of her discs live up to her contemporary reputation.

Cerdan, Joachim [bs] (1877–1921) Cerdan was a member of the Paris Opera from 1907 until 1920. He made his debut on 23 January 1907 in Bourgault-Ducoudray’s Thamara (Grand-Prêtre) and over the years assumed roles in a wide variety of works, in particular smaller roles in Wagnerian operas. He gradually took on more and more important parts, culminating in Athanaël in Thaïs, which he assumed in 1919. He took part in several creations and premiers, perhaps the most notable being that of Trivulzio in Février’s Monna Vanna and Ananda in Massenet’s unsuccessful Bacchus, both in 1909. He must have been appreciated in Massenet’s music, as he graduated from the tiny role of Nef to that of Pirithoüs in Ariane, a role created by Delmas, from which he recorded an extract on Edison, the only contemporary aural document of this music. Although most of his career took place in Paris, Cerdan also sang abroad on occasion, in Brazil and most notably in the French season in Buenos Aires in 1920. His recordings were for Nicole, made before his Opéra debut, then Edison and Gramophone, all before the First World War.

César, Berthe [so] (ca. 1880–unknown) César was born in Schaarbeek (the city files disappeared in a fire in 1911) and studied at the Brussels Conservatoire, where she was awarded second prize in dramatic singing in 1900. She sang in provincial opera houses in both Belgium and France, made her first appearance at the Opéra-Comique in the role of Philine in Mignon (1908), and went on to sing the major coloratura roles: Manon, Lakmé, Rosine, and Violetta. 1909 saw César in Marseille, where she was much appreciated (“une délicieuse chanteuse légère d’opéra-comique”) in similar roles, later adding that of Marie in La fille du régiment, and also appeared in the local premier of the then extremely popular Quo Vadis? She sang there through the period of the First World War – she was called on to interpret La Brabançonne on various patriotic occasions. In March 1912 she created the title role of Larmanjat’s Gina in Nice. She made a number of recordings for Gramophone between 1911 and 1912, in particular numerous duets with tenor Léon Campagnola and an impressive voice test for Edison, reissued by Marston (52025-2) in the Edison Trials. She was married to bass Julien Lafont.

Charbonnel, Marie [con] (Lyons, 1880–unknown) Marie Charbonnel studied music at the conservatory in Lyons, winning first prizes for piano, singing, and opera in 1901. That same year, she made her opera debut at the Grand Théâtre de Lyons in Samson et Dalila (Dalila) and then appeared there in Werther, Carmen, and Orphée. She subsequently sang at many of the major French provincial opera houses. She made her Paris Opera debut as Dalila on 2 June 1908. During that season, she also participated in the first Paris Opera performances of Götterdämmerung (First Norn) and Das Rheingold (Erda), and sang in Hamlet, Aida, and Rigoletto. The following year, she sang in Siegfried, Die Walküre, and Henry VIII. She made her debut at the Opéra-Comique on 27 October 1910 in Carmen, followed by performances in Galathée, Louise, and Der fliegende Holländer. She appeared in Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, and Monaco, and gave a number of recitals, notably at the Salle Gaveau in Paris. Charbonnel was admired as an interpreter of modern dramatic opera and she created a number of roles: Amelys in Levadé’s Les hérétiques (27 August 1905, Arènes de Béziers); Vanina in Saint-Saëns’s L’ancêtre (26 February 1906, Monte Carlo Opera); a Sorcière in Bloch’s Macbeth (30 November 1910, Opéra-Comique); and Lia in Magnard’s Bérénice (15 December 1911, Opéra-Comique). She recorded for Odéon, Gramophone, Trianon, and Opéra-Saphir. Her resplendent voice is immediately recognizable, and her secure technique places her in the front rank of French contraltos.

Daffetye, Jeanne [so] (1878–1962) Daffetye was born Jeanne-Marie-Victorine Deffayet in Paris and made her stage debut under her anagrammatic pseudonym in Bordeaux in 1897. Her Opéra-Comique debut took place on 29 October 1899 as a spirit in Cendrillon. During that season she married pianist and composer Henri Dèze. Her five seasons at the Comique were spent singing mainly small parts, including a number of creations, of which the most significant was Massenet’s Grisélidis (1901). She also created, with Lucien Muratore, Vocalisettes (1903), a play with a Massenet score. Daffetye left the Opéra-Comique in 1904 for Anvers where she sang for two seasons: Manon, Mimi, Sapho, Juliette, Rosine, Violetta, and the leads in several local premieres including Massenet’s Chérubin in 1905 and Giordano’s Siberia in 1906. She then appeared in the French provinces and Geneva, where she took part in the local premiere of D’Albert’s Tiefland. Her records, all made for Gramophone between 1903 and 1907, include a fair representation of repertoire which was already disappearing at the time.

Dupouy, Louis [ba] (1881–unknown) Louis-Jean-Emile Dupouy was born in Paris and made his debut at the Gaîté-Lyrique in 1908, where he sang Ourrias in Mireille. (He was on loan from the Opéra-Comique, where he appeared as early as 1907.) There he mostly sang a variety of comprimario roles. His most important assignments seem to have been Alfio in Cavalleria rusticana and d’Orbel (Germont père) in La traviata. He took part in some premiers (Snégourotchka in 1908) and creations, including Solange by Gaston Salvayre, from which he recorded an aria, though not from his stage role. He sang in the French provinces, for instance the 1913 summer season at Aix-les-Bains, where he sang Albert in Werther. He would be completely forgotten today, had he not made over forty sides for Gramophone (with operetta items made under the name Jean Duez) and other companies between 1909 and 1913. All of his recordings reveal a good voice and fine style.

Ghasne, Alexis [ba] (1868–unknown) Ghasne was born Alexis Bobœuf in Saint-Denis. He studied at the Paris Conservatory and made his debut at La Monnaie (1892) and remained there until 1895, performing at Covent Garden in 1893. He sang in the French provinces before entering the Opéra-Comique as Alfio in Cavalleria rusticana in 1897, soon leaving for the Théâtre-Lyrique (1899-1900), then Nice and Lyons. By 1905 he was back at the Opéra-Comique, where he took part in the creation of Erlanger’s Aphrodite (1906). As his stylish singing was considered to be perfectly suited to the music of Gluck, he was entrusted with Agamemnon in Iphigénie en Aulide for the premiere at this theater (1907), and succeeded Dufranne both as Oreste in Iphigénie en Tauride and as le grand-prêtre in Alceste. He continued to sing until the mid-twenties, making return appearances at Covent Garden in 1911 and La Monnaie in 1911-1912. Between 1924 and 1926 he also acted in several films. He recorded extensively for Gramophone, appearing exclusively on their less prestigious Zonophone label. He also recorded for APGA, including several extracts from the Gluck operas.

Heilbronner, Rose [so] (ca. 1884–unknown) Heilbronner was born in Paris, where she made her debut at the Opéra-Comique in 1907. She sang lighter soprano roles such as Mélisande in Ariane et Barbe-Bleue, Micaëla in Carmen, Eurydice in Orphée et Eurydice, and Rozenn in Le roi d’Ys. She also made occasional appearances at the Paris Opera and at the Gaîté-Lyrique (Cendrillon), as well as in many theaters and casinos in the French and Belgian provinces up to the First World War. She was particularly associated with the composer Guy Ropartz, director of the Opéra in Nancy, where she created the role of Koethe in his opera, Le pays. After the First World War she continued her career in particular at La Monnaie (1910–1921), and in provincial theaters, singing such parts as Anna in La dame blanche, Manon, Countess Almaviva, Louise, Tosca, Fanny in Massenet’s Sapho, Paul Bastide’s Vannina, and even Marina in Boris Godunov. She devoted herself thereafter mainly to concert work in France and Belgium during the late 1920s. Her best known recordings were for Gramophone, but she also recorded for Odéon, Edison, Idéal, and Ibled, all before the First World War.

Landouzy, Lise [so] (1861–1943) Landouzy was born Elise Besville at Le Cateau in October 1861. There she married cellist Fernand Landouzy in 1880. As Mme. Landouzy-Besville, she first taught singing at the music school of Roubaix and was active as a concert singer in the French and Belgian provinces, most notably at the casino of Blankenberge, near Oostende and the Vauxhall in Brussels. She was signed by La Monnaie for the 1887-1888 season, making her debut as Rosine. She remained there for two years, singing Mireille, Leïla, Javotte in Le roi l’a dit, Virginie in Le caïd (which she studied in Paris with Thomas), Rozenn, Marie, Micaëla, and others. In September 1889 she made her debut at the Opéra-Comique, again as Rosine. During the next five years at the Comique, she created Messager’s La basoche (1890), Pessard’s Les folies amoureuses (1891), and Cui’s Le flibustier (1894), among other works, and sang Nannette in the French premiere of Verdi’s Falstaff (1894), in the presence of the composer. She sang one other season at the Opéra-Comique (1900–1901) and continued appearing regularly at La Monnaie until 1903. After that point, she guested mainly in Brussels, and at the Grand-Théâtre of Lyons where her husband was co-director between 1906 and 1909. Monte Carlo saw her in 1904, singing the three female leads in Les contes d’Hoffmann. She was also very active during the summer seasons, singing in Dieppe, Vichy, and Aix-les-Bains until World War One, after which she settled as a teacher in Lyons. Her recording legacy is particularly important, comprising over 160 sides recorded for Odéon between 1906 and 1911. She also made a few rare Phrynis two-minute cylinders. She seems to have sung on stage almost everything she recorded, from Chérubin to Rozenn to Lakmé. In Landouzy’s case there is no difficulty in reconciling the voice as recorded with her fine reputation.

Leclerc, Jeanne [so] (1868–1914) Born in Liège, Leclerc made her debut at Paris’s Gaîté-Lyrique in 1888 in Grisar’s Le bossu. She joined the Opéra-Comique in 1890, where she sang most of the lighter soprano roles, including Philine in Mignon, Micaëla in Carmen, Eurydice in Orphée et Eurydice, Baucis in Philémon et Baucis, and Jeannette in Les noces de Jeannette. In 1899 she appeared in the title role of a production of Lucie de Lammermoor at the Théâtre de la Renaissance in Paris, beside Cossira and Soulacroix. She also sang in the French provinces and abroad, notably at Covent Garden, where she appeared in 1899 as Bettly in Le châlet. Her records were all made for Odéon in the company’s early years, including six duet sides with baritone, Gabriel Soulacroix.

Marignan, Jane [so] (1873–1924) Marignan made her debut at the Opéra-Comique on 7 November 1895 in the title role of Galathée. She sang Elvire in the Opéra-Comique’s premier of Don Giovanni and Eurydice in Orphée. Her other roles were most varied, from coloratura parts such as Dinorah in Le pardon de Ploërmel to Zerline in Fra Diavolo to more dramatic ones such as Santuzza in Cavalleria rusticana and contemporary ones such as Phryné in Saint-Saëns opera of the same name. In 1908 she sang at the Théâtre-Lyrique in Paris and in 1909 she sang Aida at the Opéra. On the French provincial stages, she was particularly appreciated in Massenet operas, especially Thaïs and Sapho. In Bordeaux she sang those roles in addition to Lakmé, Gilda, Violetta, Rosina, Micaëla, and even Carmen. When she retired, she ran a shop selling Pathé records. Pathé was the company for which most of her records were made, about forty selections, both cylinders and discs. The most interesting part of her recorded repertoire, six extracts from Massenet’s Sapho recorded in 1904, have never come to light. Marignan also made a small number of Lyrophone and Apollo discs.

Martini, Marie-Louise [so] (unknown) Little is known about this soprano who seems to have been active in Paris at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was long thought that the Mme. Martini, who made records for APGA in 1907, was Marguerite Martini, a dramatic soprano with an important career at the end of the nineteenth century. From the documentation published by APGA, it is clear from the signature that the Mme. Martini who signed an exclusive contract with the company 15 May 1907 is not Marguerite but Marie-Louise Martini. She also appears under this name on the Excelsior label during the same period. Marie-Louise Martini was on the roster of the Ghent Grand-Théâtre (now the Grote Schouwburg) 1906–1907 as a guest artist (as was Jean Noté, which may explain the link with APGA). In August 1910 she was singing in the Revue of the Geneva Kursaal and also sang in at least one concert classique. She sang in Boston during the 1911-1912 season, and was heard immediately after the First World War in Marseille, singing coloratura roles, and was engaged as chanteuse légère by the Opéra d’Alger for the 1919-1920 season.

Martyl, Nelly [so] (1884–1953) Martyl was born Nelly-Adèle-Anny Martin in Paris, started singing minor roles at the Opéra, but soon moved on to the Opéra-Comique, making her debut in the premiere of Isidore de Lara’s opera Sanga in 1908. She was chosen for the title role of Ernest Garnier’s Myrtil, which had eight performances in the 1909-1910 season. She continued to sing the lighter soprano roles, such as Anna in La dame blanche, Rozenn in Le roi d’Ys, Sophie in Werther, but also undertook leading roles, Manon, Mimi in La bohème, and Jacqueline in Messager’s Fortunio. Having married painter Georges Scott de Plagnolle (1873–1942) in July 1909, she followed him to the front when World War One broke out. He was a war correspondent for the weekly L’illustration, and Nelly served as a nurse for the length of the hostilities, becoming the incarnation of the French war nurse, and was decorated with the Légion d’honneur in 1920. During the 1920s she was often heard in concert, inaugurating for example a series of melodies by Louis Ganne at the Salle Gaveau. She was also active in opera. In Monte Carlo, for example, she sang La bohème and contemporary works – Les demoiselles de Saint-Cyr, Les noces tragiques, the posthumous creation of Massenet’s Amadis with Margherita Grandi as “Djéma Vécla”, and Costa’s Le capitaine Fracasse – between 1921 and 1931. In the theater, she performed the role of Solveig in Grieg’s Peer Gynt over 140 times. This was presumably both spoken and sung, as it was advertised with Grieg’s incidental music. A strikingly beautiful woman, as the exquisite portraits by her husband attest, Nelly Martyl left many photographs and postcards, but only two recordings, both duets. The one included here is in fact subject to some controversy. The label attributes the soprano part to Martyl, but Alan Kelly’s French Gramophone Company discography lists Suzanne Brohly. Martyl’s only other record is a fine “O Magali ma bien aimée” with tenor Edmond Tirmont.

Régis, Georges [te] (unknown) It is thought that Régis made his debut in Marseille in 1898 where he returned for the 1899-1900 season. His Paris appearance was as Weber’s Oberon at the Théâtre-Lyrique in April 1899. In 1902-1903, he went to Bordeaux, singing opéra-comique leads and high-lying second tenor parts in grand opera: Léopold in La Juive, Ruodi in Guillaume Tell, and Jonas in Le prophète. He returned to Marseille before sailing to New Orleans for the 1905-1906 season. His Paris Opera debut took place in June 1909, but he spent most of the following season at New York’s Metropolitan. London heard him in 1912 as Almaviva at the Hammerstein Opera House. By the mid-twenties he was back at the Opéra, mainly as a comprimario, but still singing Ruodi and taking part in creations such as Roussel’s La naissance de la lyre (1925). He recorded a substantial number of sides for French Gramophone and a few unpublished Edison discs.

Soulacroix, Gabriel [ba] (1853–1905) Soulacroix, born Gabriel-Valentin Salacroix in the Southwest of France, had an extremely striking career, encompassing a number of prestigious opera houses and an unlikely array of roles. He studied in Toulouse, then at the Paris Conservatoire with Masset and Mocker. After second prizes in singing and opéra-comique in 1878, he was signed by La Monnaie, where he made his debut as Escamillo, was the first Papageno (1880), and the first Beckmesser (1885). During his seven seasons in Brussels, he was a regular spring guest at Covent Garden, where he made his debut in 1881. This came to an end with his engagement at the Opéra-Comique, where he was a favorite as Figaro and where Hérold’s Zampa was revived for him. He was the first Clément Marot in Messager’s La basoche (1890) as well as Ford for the French premiere of Falstaff (1894), among many other creations. He was on stage with Cécile Merguillier when the May 1887 fire started (his behavior on this occasion earned him a medal). After nine seasons at the Opéra-Comique, he left to star in a successful revival of Planquette’s Rip at the Gaîté, where he also created the same composer’s title role in Panurge (1895). He was then back to La Monnaie and Covent Garden (1898), sang Beckmesser at La Scala under Toscanini, spent one season at the Théâtre-Lyrique, was heard at the Gaîté-Lyrique again, extensively toured France, and basically sang everything everywhere, from saucy operettas with Milly-Meyer at Fursy’s cabaret to La traviata in Saint-Petersburg with Cavalieri. Soulacroix was also a regular at Monte Carlo, where among many roles he was the first Prior in Le jongleur de Notre Dame (1902). By the end of 1903 he was back at the Opéra-Comique. He died at Chalet Rip, the home he had built with his fees from the operetta run, in Soturac, a small village near his native Fumel. An abundant discography of over 100 sides preserves his vividness as performer.