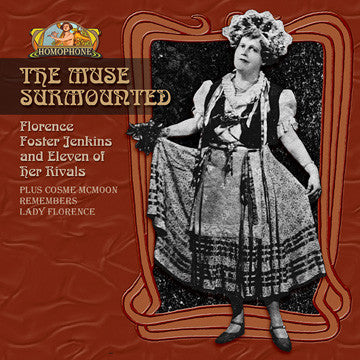

Robert Levine in Classics Today said “This has to be heard to be believed, and believe me, it has to be heard ... This is priceless as a study in aberrant behavior, the history of opera, and sociology ...” Larry Holdridge in The Record Collector felt the singers contained in this compilation “...are demonstrating music from a different perspective. Theirs is simply the joy of performing without being restricted by the printed score and vocal technique ...” Rick Robertson for Amazon stated The Muse Surmounted “... is an uproariously funny excursion into what I would label ‘mal canto’. Each singer in this collection set her own substandard for vocal art, and each one is presented in transfers that allow the holes in one's technique to shine through. Brightly.... This is also a first-class production, with attention to quality in presentation. The program notes alone are worth the price of the CD. Gregor Benko has carefully researched these singers, often waiting years for leads to information.... ” (This is issued on the Homophone label.)

In a recent scholarly work, Mr. Ethan Mordden explained and unraveled at great length a particular mind set in which peculiar divas, during operatic performance, shift any sense of reality into their character’s state of being. That is to say, there is a reversal of entity wherein the fiction becomes truth, and the vice becomes versa. The term for this state of actuality, coined by the Metropolitan Opera standees of the 1960s (among whom I was indeed numbered), was “demented.” Dictionaries report that dementia is the deterioration or loss of coherent thought. In opera, however, it is rather the extremely coherent transference of pedestrian, work-a-day thought to that of voice; in which the world is sung rather than merely mentioned. Those of us who try to live in that world, among those holy ones who are in this way demented, reside in The World of Voice. We listen to our recordings during every possible moment because these records tell us precisely what we want to hear and never have one word or note of untruth or harm. What is heard is the total and uncompromised dedication to voice, and that is the state of reality.

It need not be said that beauty of voice has much to do with industrial strength singing —- although it might help. How many times have we brought home a recording of a soprano bearing a voice of great pulchritude only to find that the record should have been titled “Madame Whoever Sight-reads Again”? How many times have we gone into the opera house to witness a tenor entering the stage, beaming at the public with his “Here I am, you lucky bastards” grin, to deliver Nemorino in his best Cavaradossi style? Where is that immersion into transfixed dedication? How about sincerity of the heart? Where is the mandatory psychosis without which voice is merely song?...and we can all sing a song.

Were there no opera house, no recordings, no radio, TV or other public venues, those among the truly dedicated would sing regardless. The Callases, the Prices, Melbas, Oliveros, Zeanis, Ponselles and Gianninis would all be on street corners singing their particular souls to all that would hear, and the Puccinis, Verdis, Wagners and Rossinis would be handing them page after page as one might fuel a furnace. Those whose souls are inscribed to voice uncompromised will, must and forever sing.

The compact disc which accompanies this booklet is an ultimate survey of those whose involvement and undeviating sincerity transcends things auricular. It is a document of something otherwise intangible: consummate dedication. I personally witnessed several performances in the opera house where involvement and dedication stilled the air: Maria’s Tosca. Leonie’s Senta. A particular Steber Tosca, and there were others. But how many divas have carried their dementia off the stage into their daily lives? There have been some, to be certain. From what we can know of Melba, surely she was more of a voice than a regular mortal; the same we have found of Patti. Milanov was such an entity—made most obvious even in her otiose conversation heard during opera intermission features broadcast in years past. Callas was so much so that if one chose to compose an opera using her life as the subject it would be truly redundant. Sutherland however was just plain Joan. Sills was like butter. Peters the consummate Scarsdale matron. This is not at all to detract from these women’s high point of artistry, but they could never hit that point so magnificently over the brink.

A true story is told about three divas of the not-so-distant past who were imposed upon to appear at a luncheon given by the bluebloods of the Metropolitan Opera Guild. Of course the three luminaries were invited to give the well-heeled old dames the thrill of an elbow- rub so that they might be moved to part with a portion of their aristocratic funds to benefit the Guild. At some point one of the three decided to give the Guild ladies a special thrill and rose to give forth a capella with her legendary “Un bel di,” albeit thirty-five years after her initial history was made. The two less extroverted prima donne sat and listened when one turned to the other and remarked “Thank goodness we don’t have that disease!” Disease? Obviously she meant the disease of not knowing when to jump the vocal ship. But pause to think—was it for certain that disease, or a mere display of foolish ego? Perhaps rather it was heartfelt dedication and Pavlovian instinct sparked by a potential audience that drove her uncontrollably to lose herself yet again into the life of Cio-Cio San.

Our survey is designed to include only women artists who are no longer professionally active and are definitely or probably dead. Perhaps on first hearing, the women on this compact disc might appear vocally different from many we have heard. Perhaps some listeners might perceive them as unusual or extraordinary in one way or another. However, upon further hearing one begins to clearly realize the dedication—the sincerity and uncommon involvement that all these women have. No matter how one perceives their art, I’m certain we will all happily concur in the long run that they were all solidly, and to be sure, thoroughly demented in a very specific way—and multitudes will now have the opportunity to join us in thanking providence for that.

HOMOPHONE ORCHESTRA

1 CARMEN: Potpourri (Bizet)

ROSALINA MELLO (dates unknown)

2 Fado Celestial (Traditional) [Portuguese]

American Columbia 84792, ca. 1920, orchestra unidentified

“...Rude vocal utterances of the people...”

Those special qualities of undeviating sincerity of the heart and transfixed dedication are not solely the provenance of opera’s songbirds. Such elemental states spring directly from the earth itself. They are sometimes exhibited in the rude vocal utterances of the people, but only rarely documented, as in this reissue of an historic disc of an otherwise unknown singer. Here each of the four expositions of the refrain, so unvarying in their pathos and poignancy, add up to a Gesamtkunstwerk wherein performance perfectly matches composition.

ALICE GERSTL DUSCHAK (1904–1994)

3 Reigen (Weber) [German]

Educo 4050, March 1987, David Garvey, piano.

“....The first teacher at Peabody of Jessye Norman...”

These rare qualities sometimes irradiate the work of serious concert singers also. Mme. Duschak, one of the most beloved teachers at Baltimore’s Peabody Conservatory, was certainly thus illuminated. She taught continuously for forty-five years starting in 1945. Conductor Dmitri Mitropoulos (1896–1960) probably heard her in New York in 1941 when she created a small part in the world premiere of Benjamin Britten’s first opera, Paul Bunyan, and later recommended her when Peabody was looking for a teacher of lieder. The Duschaks had emigrated to London in 1937, and in 1943 came to the United States, eventually settling in Washington.

Alice Gerstl studied for the opera in her native Vienna and first sang on stage at the age of

nineteen. She said she had been “the leading lyric coloratura at the Opera House Muenster,” where she sang the Queen of the Night, Annchen in Der Freischütz and “all merry, high soprano parts.” Her idol was Marie Gutheil-Schoder (1874–1935), a great Elektra. But she became infected with a love for German poetry and lieder and simultaneously pursued a career as a concert singer, reaching her apogee in a collaboration with composer Ernst Krenek (1900–1991), premiering many of his songs.

In a 1985 German newspaper interview she said she was especially well suited for atonal lieder, the interviewer reporting that “she did not know the difference.”

At some point she married Dr. Gottfried Duschak, but we have been told that their married life was difficult -sometimes at the Conservatory she could be seen with the marks of his physical abuse. One proof of Madame’s enormous physical stamina occurred in 1984 during her husband’s final illness, when for a protracted period she stayed up with him all night in the hospital and then commuted from Washington to Peabody in Baltimore daily to teach.

Things were never the same after his death, and a student has admitted that she became a bit dotty, with her silly black wig always askew. At the time the Conservatory had another Grand Dame, Flor Wend (1909–1989), whose specialty was teaching French chanson, and who everybody adored. Everbody but Madame Duschak, that is, and the two often indulged in unladylike behavior in the halls and elsewhere, sometimes coming close to physical violence!

An unsigned, affectionate reminiscence of Madame Duschak was published shortly after her death, from which we quote: “High spirited and quick tempered, with just a touch of vanity, she was unburdened by patience. Nothing was ever quite so alarming as an unhappy Madame. Age was a concept she never grasped. In the 1960s when hemlines ascended above the knees of Peabody’s women students, hers went right up with them. After a certain number of silver threads appeared in her hair, we never saw it again. The idea that you might someday want to stop singing never occurred to her...Peabody became her family and we were all her children. All of us found her at least as difficult as our parents.”

It would be a superfluous imposition for us to say much about her song, for in the liner notes Mme. Duschak herself wrote the following of Weber’s setting of the poem by Voss: “This composition presents a wedding—dance song—conversation. Everybody enjoyed the festivity. The music in the accompaniment is on purpose a bit off tune. One is reminded of pictures of Peter Breugel the Elder called peasant Breugel from Amsterdam (c. 1525–1569). Interesting is the influence of painting to music of about 250 years earlier. This given example exemplifies the inter-relationship of the arts.”

She recorded six LPs of lieder for the obscure vanity label Educo. It should be mentioned that seven of her students were winners of Metropolitan Opera auditions. And that she was the first teacher at Peabody of soprano Jessye Norman (b. 1945).

BETTY-JO SCHRAMM (dates unknown)

4 ARTASERCE: Va tra la selve (Carl Heinrich Graun) [Italian]

Private LP, recording date unknown, orchestra and conductor unknown

“…unsung pioneer of the Early Music movement”

Little is known about this recording, extracted from a private LP record with a blank label that appears to date from the late 1950s, and that was discovered after his death among the effects of critic Harold C. Schonberg. Inside the record was an index card hand-lettered with the selection title and the artist’s name. Despite the mystery, Schramm undoubtedly deserves inclusion among our select offering. Surely Madame Schramm was an “unsung” pioneer of the Early Music movement, vividly bringing to life the florid Baroque music that most of her contemporaries dared not attempt. It is not surprising that this amazing document would be among the treasures in the collection of such an esteemed music critic and scholar. As the rare item reveals, La Betty-Jo was also far ahead of her time in the field of historical performance practice. Uncannily, the voice appears naturally tuned to Baroque pitch. Apparently she was singing Early Music a half-tone flat long before it became fashionable to do so.

While there is no story to relate concerning Betty-Jo Schramm, there is an interesting story about the composer. Graun was Kappelmeister of the Berlin Opera under Frederick the Great, who earlier was a bit too artistic for his father’s taste. Concerned, his father (King Frederick William the First) had forbidden Frederick to study music, denouncing such activities as “an effeminate pastime.” Frederick began to regularly play on the flute anyway. He ascended to the Prussian throne in 1740, three years before Artaserce was written. It is said that Graun and the monarch struck up an unusually close relationship. The New Grove calls it a “ a strong friendship” and states that the news of Frederick’s defeat in a battle at Züllichau “probably hastened Graun’s premature death.” Certainly the friendship was more difficult for Graun than for the king, for it seems Frederick was a sadistic boor as well as a tease. Should Graun not succeed in satisfying, Frederick would call upon his court composer and flute teacher, Johann Quantz (who had taught Frederick to play on his flute, and was a master flute maker as well. He had added extra keys to the instrument, offering the largest flute on which Frederick had ever placed his mouth.) It appears the King was also eine Königen der Opera. He insisted on inserting some arias of his own composition into the operas of Graun, and felt no compunction about ordering the composer to replace arias he didn’t like. “Demofoonte,” a Graun opera dating from 1746, went to the stage with the imposition of three of Frederick’s arias! Even more humiliating was the King’s insistence that his special friend rewrite an aria that displeased him. Graun dutifully did so, saying he had done his best with the rewrite. Still Frederick wasn’t satisfied and had an aria by Graun’s great rival, Johann Adolf Hasse, inserted instead. What a boyfriend! Today, with the legalization of gay marriage, this behavior would certainly be an actionable reason, Graun’s for divorce!

TRYPHOSA BATES-BATCHELLER (1876–1952)

5 MARGITA: Canzonetta (Meyer-Helmud) [German]

Melotone 97, ca. 1945, accompanist unknown.

“....Sang at the White House...”

The recent, sensational discovery of the unknown Bates-Batcheller gramophone discs as well as the re-discovery of the true story of Florence Foster Jenkins—together were the catalysts for this long-simmering pot-au-feu, about which the producers had been fantasizing for several years. Of the Bates-Batcheller Aufnahmen only one copy each of two discs survive, the pair comprising the total of known recordings of Tryphosa’s art. Could others exist? Were they recorded for the artist? Might they have been recorded at the express wish of the Maharaja?

We do know that La Tryphosa returned to the United States from her long Paris sojourn in 1941, after her husband’s death; it may very well be that a far-sighted executive of the Melotone label induced Bates-Batcheller to record after Jenkin’s demise in 1944, hoping to recreate the unexpected and probably very lucrative furor unleashed by the issue of La Florence’s records. Why, we wonder, might these Bates-Batcheller recordings have remained so undeservedly unknown for so long (for certainly they are not without a certain lack of unique vocal splendor, if not historical importance)… if it were indeed not for sinister machinations of the few remaining, psychotic but yet-potent Jenkinsonians, previously known to ruthlessly crush other potential rivals to their divine Florence Foster, for them the only Goddess, their anointed one? The knowledge of the full and sordid story of Mme. Jenkins which eventually follows prepares us for that possibility.

Privately educated in France and America, Tryphosa graduated in the 1899 Radcliffe College class. She apparently was able to study with almost any teacher who accepted money, and she seems to have had lessons with Sir George Henschel (1850-1934), Matilde de Castrone Marchesi (1821-1913), Giovanni Sgambati (1841-1914) and other luminaries such as Vela and Bimboni in Italy and B. T. Lang and Giraudet in America. According to the 1906 volume Who’s Who in Music and Drama, after Tryphosa Bates married a wealthy shoe manufacturer named Francis Batcheller in 1904, the two left their native North Brookfield, Mass. and made a home in Paris, France. (We can assume she hyphenated her surname after marriage to retain her artistic independence and preserve her musical identity.)

Wealth enabled her, and Tryphosa made her debut at the Salle Erard in Paris in 1900 with Monsieur Maugin, conductor of the Opera, at the piano. At the many parties she attended Tryphosa would sing, sometimes performing chansons by Jules Massenet, with the composer graciously accompanying her. In 1904 she made her professional debut in Boston, and “the critics of that city, so extremely conservative in musical matters, vied with each other in expressing their praise in enthusiastic terms,” as reported by the Musical Courier for March 16, 1904, which put La Tryposa on the cover and also printed: “Mrs. Bates-Batcheller is gifted with a beautiful soprano voice of the oldtime lyric [Etelka] Gerster [1855–1920] quality, that has been supposed by musical judges to have disappeared among the artists of the present day.” Astonishing as this may seem to us as we hear her records, even more unusual is the fact that the quote is found among a full page of reprints of very minor reviews of Bates-Batceller recitals from the Boston area, reading almost as if such saturation coverage could have been purchased.

La Tryphosa’s musical and other means also bought her another cover photo and a substantial amount of coverage in the Musical Courier for July 25th, 1906, which issue wisely observed: “....there was but one opinion about her style and art...there are few women today who have used more time, more means...to attain their ends...astonishing in a woman of her high social position.”

Not incidentally, Mme. Bates-Batcheller was more than proud of her impeccable genealogical lineage. Her New York Times obituary stated that she had been descended from Stephen Hopkins (who signed the original Pilgrim’s Compact as he came over on the Mayflower); that she was a member of the National Association of Americans of Royal Descent, as well as the Magna Carta Dames, the Daughters of the Barons of Runnemede, the Society of Mayflower Descendents, the Daughters of Colonial Wars, the Daughters of the Society of Cincinnati, and that she had been decorated by six kings. She personally founded the Rochambeau Chapter of the Daughter of the American Revolution in St. Cloud, France, for which deed she was awarded the cross of officer of the French Legion of Honor. She even sang at the White House.

Such honors come only to those who are either talented, or accomplished, or well-placed, or very wealthy. They do not always come unsolicited when awarded for this latter reason; in striving to achieve them Tryphosa found her occupation. Bates-Batcheller left to posterity five books, one of which (The Soul of a Queen) is a novel. Whether this legacy is fortunate or not remains uncertain. The other four of her tomes (with titles like Royal Spain of Today) all take the form of curious, insufferable travelogues detailing to the minute Madame’s individual little triumphs in a relentless, unabashed social climb among the aristocracy.

In Glimpses of Italian Court Life (New York: Doubleday Page and Company, 1906) from which we quote, the Diva Assoluta also reveals bits of personal information. Browsing in the volume’s sumptuously designed pages, we perceive Tryphosa as blissfully unselfconscious, apparently never suspecting she might one day be judged by some future readers to have been self-centered and neurotically obsessed with mingling with aristocrats and royals—even, dare we say it, that she was un peu superficiel. She gushed for hundreds of pages about the princesses and queens she had met; at the same time revealing that she was perhaps just a tad deficient in literary talent. Here’s a random sample from page 20:

“These Neapolitan merchants are most artistic, and have copied and reproduced successfully many of the necklaces found in Pompei, now in the museum of Naples. The museum claims us tomorrow, and that reminds me, I am sending home a lovely bronze Mercury, found at Herculaneum. It is the most perfect thing in art, I believe. Charles Sumner left his replica, you know, to dear Mrs. Howe.”

Then a few sentences later she abruptly breaks into a discussion of music, telling us: “Most of the composers who try to write ‘after Wagner’ are a long way after him.” Her sense of humor matches her talent! (Another living such example is exhibited in Tryphosa’s chuckle on the words “hat er keiner lied” in her aria recording).

In one sparkling incident we learn: “Last week [Editor’s note: this would be the second week of February, 1905] our [Italian] Ambassador gave a brilliant reception, and asked me if I would sing. People were really enthusiastic about my voice; when I finished the aria from the Magic Flute, a well-known gentleman from Philadelphia, standing near F. B., said to him in a very earnest manner, ‘Really a remarkable voice, don’t you think so?’ F. B. laughed and said, “Well, yes, I enjoy hearing it every day; the singer is my wife.” Later, discussing Giovanni Zenatello (1876–1949), she tells us: “Good tenors are very rare, and so many of the best ones seem to come from Italy.” Such expert first-hand accounts are the stuff of which dissertations are made! And on page 201, she gives us her artistic credo: a singer may have all the heart and temperament in the world, but without technique she can but ill express her feelings, however deep they may be.

Not all, however, is deep thought interspersed with humor in this book, for Tryphosa occasionally mines the historical vein: we are told that in 1905 she met Zinka’s [Milanov] (1906–1989) teacher Milka [Ternina] (1863–1941) and they agreed that Salomea [Kruszelnicka] (1872–1952) was straining her voice too much. There is a rare glimpse of Mme. [Matilde] Marchesi: “’it takes fourteen things to be a great singer,’” she often says, and she is right: the voice is only one, and common sense comes in a very close second. One must study human nature a fond and one must live and love and suffer before one can become an artist.”

It is subtly obvious in these books that Tryphosa’s life was not without suffering and even humiliation. She and her husband ( “F. B.”) were mightily restricted in their climbing by their own very disadvantageous Catholicism. England was closed to them, and they had to limit and concentrate their strenuous European social efforts ever upwards merely to the Catholic courts, like those of Italy, the Vatican, Portugal and Spain. Thus we can see how Madame Bates-Batcheller integrated Madame Marchesi’s advice with wisdom gained of her own tribulation...and how we all want to and do suffer with her when she sings!

Erik Meyer-Helmud (1861–1932) wrote several operas, of which Margita, composed in 1889, was the first. For Tryphosa, this was new, if not avante garde, music. Concerning this, we are rewarded in the same book with a glimpse back in time, for Mme. Bates-Batcheller unintentionally gave historic background and precedent for her major recording, presented here. She had just finished singing an aria from the Magic Flute at a “mixed concert” on April 3, 1905 in Italy in honor of H.R.H.’s the Duke and Duchess of Connaught: “His Royal Highness...asked if I would sing again, and knowing that the Duchess is German, I sang… a very brilliant Canzonetta from an opera by Meyer-Helmud, ending with a trill ‘a mile long,’ as the girl said...When I had finished, the Duchess came to me in the most charming way and said, ‘You must have spent many years in study to acquire such perfect technique, and you sing with so much feeling as well.’ I said I was very happy if I had been able to please her.”

One perspective from which posterity must consider Tryphosa’s recording of Meyer-Helmud’s effusion is certainly the artiste’s echt-Deutschissche penetration and staggering understanding of the murky depths of the aria. Again song and singer mesh, matching creator and re-creator! Will Meyer-Helmud’s aria ever have another such champion?

And there is yet another perspective from which we can view La Tryphosa as one of the elect. Fortunate is she to have had a unique Christian name, the name combining with the art to catapult her to a kind of immortality, joining her to the ranks of other divas instantly recognizable by mere mention of their first names: Bidu, Cathy, Conchita, Eleanor, Frida, Gundula, Kirsten, Licia, Ljuba, Mawrdew, Nan, Nina, Zinka and (more problematically), Maria. And to have that unique name, those seductive sounds—“Try - pho - sa,” (so suggestive of three times pleasure, triple our fun), conjoined to one of opera’s ubiquitous hyphenated surnames! Gutheil-Schoder, Fleischer-Edel, Huni-Mihacsek, Parsi-Pettinella, Hafgren-Dinkela, Galli-Marié, Galli-Curci, Galli-Campi and Güdt-Galli (Mysz-Mali) come to mind. And now, Bates-Batcheller!

“Foster Jenkins no longer best

For Tryphosa’s twice bless’d,

Goddess of art and appellation!

She leads all the rest

Having conquered each test

Of tone and aspiration.

Quake, O Neriani, and Tremble!

For the records of Tryphosa

We doth here assemble!”

Gregoire de Binqueaux

NATALIA DE ANDRADE (dates unknown)

6 MANON: Je marche (Massenet) [French]

LP, ca. 1960, piano accompanist unknown

We have almost no information to impart for this artist, who was born in Portugal and died there sometime during the stereo LP era. Apparently she began as a kind of folk/popular singer, and made some 78 rpm records in that genre. At an unspecified time she began to sing minor parts in new Portuguese operettas and operas at second-string theatres. Later she began giving public performances of opera arias, and a public for her art began to grow. She had a quirk, often stating that she sang for herself and had no interest in the public, yet always found a way to appear in public. In her old age Natalia had little money, but saved and scrimped and paid for performances and recordings. Someone who has seen the original LP from which this aria is taken states it has a wonderful photo of her in her old age, wearing a pair of culottes. Our copy stems from a tape passed hand to hand among fans. We hope a copy of the LP will come our way and that it will contain some biographical information, as well as the photo. Here we present an artist’s conception of what she must have looked like. As for her singing – listen, and you will hear why she belongs the elect. She is certainly one whose dedication and sincerity should be recognized.

HOMOPHONE ORCHESTRA

7 SAMSON AND DALILA: Bacchanale (Saint-Saens)

OLIVE MIDDLETON (1891–1974)

8 IL TROVATORE: Miserere (Verdi) [Italian]

ca. 1966, LaPuma Opera Workshop Orchestra

“...Dispensing her golden showers for decades...”

Critic John Ardoin wrote that the special quality Olive Middleton had to give her audiences at the concerts (many fortunately recorded) of the La Puma Opera Workshop was simply “love.” She was approximately seventy-five years old and had been dispensing her golden showers for decades when the La Puma performances took place at the Palm Gardens, a ballroom on New York’s West Fifty-Second street. Reading the interview with her in the March 5, 1966 issue of Opera News, one is immediately struck by something unusual: the venerable magazine refers to Dame Olive’s “extraordinary audience of flamboyant young men...” In reviewing La Olive’s Aida, it stated, “From Miss Middleton’s first appearance, in a costume of orange fringe and gold sequins, she had her fans at her feet.”

A native of England who studied in Paris with the famous American singer Emma Nevada (1859–1940), she made her debut sometime in the 1920s at the Aldwych Theatre in Dame Ethel Smyth’s (1858–1944) The Boatswain’s Mate. She sang major roles by Mozart, Puccini and Gounod with the British National Opera at Covent Garden under Sir Thomas Beecham (1879–1961) in casts with Maggie Teyte (1888–1976) and Florence Austral (1894–1968). She joined the Carl Rosa Company later at Covent Garden, and sang under the name of Olive Townsend or sometimes, Townsend-Morelli, combining her maiden name with her husband’s professional name. She sang guest performances of Nedda, Butterfly and Mimi, with Eva Turner (1892–1990) as Musetta. “Sir Thomas later told me,” she told Opera News, “‘You were always my best Susanna.’” She toured Italy and France and sang throughout the British Isles in concert, oratorio and recital.

After the War she and her husband emigrated to America at the urging of Olive’s friend, soprano Marie Powers (1910–1973), who was to become a member of Madame Middleton’s entourage. (Marie Powers in fact lived with Olive Middleton during the last two years of her life, dying in her home). La Olive emerged to give a New York Town Hall recital in 1947, one review stating “Miss Middleton, a soprano of lyric intentions, was not too wise in attempting such a massive aria as ‘Ah Perfido!’..the tessitura was too high, with the voice being pushed beyond its modest capabilities and much off-pitch singing resulting.” Listeners can thrill here to Dame Olive’s high A flat, sung with white hot conviction, and make up their own minds about this upstart criticism!

For whatever reason, she performed in no complete operas for some years, returning at last to sing a Gretel in 1951, with Pietro Spada. “I thought the role too heavy for my voice, but he insisted, and actually it suited me very well. That’s what started me back in opera. I didn’t stay long with Maestro Spada; he considered my voice too light for Donna Anna.” She began singing at a workshop, where the pianist for the performances, Josephine La Puma, was the mother was the well-known assistant conductor of the Metropolitan Opera, Alberta Masiello. “I hadn’t been with Mrs. La Puma long when she let me sing Donna Anna. Really, the best part of my career has been with the La Puma Opera Workshop, my happiest days. Do you know that when I sang Tosca, my audience strewed the stage with roses? Have you ever heard a Tosca applauded for the lines ‘Avanti a lui tremava tutta Roma?’ Well, I have been, every time; and I’ve had to learn new roles to please my public. One evening when I was doing Sieglinde, a young man came to my dressing room and asked, ‘Madame, do you sing Norma?’ I said I didn’t. ‘Then you must learn it,’ came his reply. A year later, he again came to my dressing room, asking sternly, ‘Do you know Norma yet?’ I’m preparing it, I said, and finally I sang it. It was such a success I had to repeat it three nights in a row!” The end of the Opera News article reads “At present Olive Middleton is learning Lady Macbeth. ‘I love to sing...that’s why I returned to the stage. There’s another reason too. I always wanted to die onstage—drop in my tracks. I’ve always thought it would be a wonderful way to go. I’ve died onstage, all right, at the end of almost every opera. Yes, I came back to die — but so far I’ve kept on singing.’”

Gentle friends of the Diva’s from her golden days have told us that she also was perhaps a bit dotty, regularly mentioning to each that she was about to embark on a world tour, just as Norma Desmond was about to pose for her close-up for Mr. DeMille. We are proud to provide a spotlight for her here. As Nicholas E. Limansky has wisely written, “Her vocal art transcended the verismo approach and ideal and centered on realism combined with a vocal technique that had been lost for many decades.”

NORMA-JEAN ERDMANN-CHADBOURNE (1899?–1975?)

9 AIDA: Tomb Scene: The Fatal Stone (Verdi) [English]

Westchester W 101, 1960, Allen Rodgers, piano

(with her husband Ellis Chadbourne, listed on the record as “Thomas Garcia”)

“...An example of sustained, drawn, bloomed tone...”

Mme. Erdmann-Chadbourne’s voice was presented on several obscure LP discs, perhaps the most interesting of which is entitled “Messa di Voce.” It was produced in conjunction with a book, “The Art of Messa di Voce: Scientific Singing,” written by Norma-Jean and her husband, Ellis Chadbourne. The artiste introduces that disc with a short spoken discussion of her most recent theories, transcribed in part here:

“This is one of the most unique records available today. Its purpose is to present and demonstrate the re-discovered art of Messa di Voce singing...This record challenges you to the dramatic experience of a revolutionary approach to tone versus noise. Here is an example of sustained, drawn, bloomed tone!... by using the right technique, the art of Messa di Voce, the singer will acquire complete versatility in the use of his voice...As you listen to this song I suspect you will be saying or thinking to yourselves, ‘Oh, I can do better than that,’ and I am quite sure that you can. You must remember, I am past seventy years of age and have only recently discovered the secret techniques of this so-called lost art. But you, who have many years before you, can perfect the art, and I hope to aid in restoring singing to its rightful heritage as the noblest and highest of all the arts...” She ends by dedicating the record to her late husband for his “...untiring effort in his profound research which has made this Messa di Voce demonstration possible.” Interestingly enough, although she is supposedly demonstrating the use of Messa di Voce on this recording, experts have failed to detect a single instance of her actually using the technique at any point.

She came from Chillicothe, Ohio. Nevertheless, surely Norma-Jean was predestined to occupy the place she attained in the history of opera. Her illustrious uncle, the prominent New York surgeon Dr. John F. Erdmann (1864-1954), early in 1921 operated six times on the great Enrico Caruso (1873–1921) at the tenor’s residence at the Vanderbilt Hotel, to drain an empyema. Dr. Erdmann wrote later, “When his chest was opened, out poured the foulest pus I think I’ve ever seen or smelled.” (R. Pritchard: The Death of Enrico Caruso, Surg Gynec Obs 1959; 104, page 118).

She studied in Boston at the New England Conservatory under (Myron) William Whitney Jr. (1872–1954), who was then the leading proponent of the Messa di Voce method of singing. He learned it from his father Myron Whitney Sr. (1836–1910), who in turn had learned it in Florence from its originator, Luigi Vannuccini (1828–1911). Tenor Richard Conrad remembers references made in his youth by both his teachers and older colleagues in Boston, as well as his friend Eleanor Steber (1916–1990), to Norma-Jean Erdmann as the possessor of a ravishing voice; apparently she had a stellar local reputation as an oratorio and concert singer. Steber sang the minor role of one of the merry men in a Spring, 1934 Boston production conducted by Arthur Fiedler (1894–1979) of Reginald de Koven’s (1859–1920) Robin Hood (dates unknown), in which Norma-Jean starred as Maid Marian.

Unbeknownst to them, tens of thousands of music lovers have already heard Norma-Jean, as well as her husband , for it is they who comprise the dream duet, disingenuously billed as “Jenny Williams and Thomas Burns” in the infamous “Faust Travesty,” presented as filler for Florence Foster Jenkins’s LPs. That “Faust Travesty” (including the famous trio arranged as a duet and sung in English) has become a minor legend, notorious among aficionados of this kind of singing. Few will believe that the original recordings were made to be sold as demonstrations of proper vocal technique and correct method! The true identification of the singers is here revealed for the first time.

“Tom” Chadbourne and Norma-Jean once had their own conservatory in White Plains, New York —- they had pedagogy in their blood. Each was obsessed with various techniques and schools of thought on the subject of vocal technique, and they made several other records demonstrating their theories. Starting as exponents of the Messa di Voce method, at some later point they switched to the method espoused by one Douglas Stanley (1890–?). Stanley held that it was not breath control that supported the voice, but rather, vibrato. In his pamphlet entitled “The Science of Voice,” published in 1931, he wrote (and we quote to help explain in part why many of the artists here sang as they did):

“The belief that a great voice is the result of certain anatomical gifts and peculiarities of the individual possessing it has been universally held. This idea is totally fallacious. It is theoretically possible for any healthy human voice to produce sounds equal to or better than those phonated by the greatest living artist...What takes the place of breath control (a fallacy) is vibrato...” J.W. Fay wrote, when reviewing the original publication of Stanley’s work: “Professors of the vocal art still purvey secret methods of voice placing, mysterious arts of breath control and tricks of register, much as apothecaries of old did a bootlegging business in love philtres…”

Norma-Jean was not fortunate in her choice of mates, for Chadbourne’s personality overwhelmed her. Who knows what she might have achieved had she not married the man she did? Earlier he had taught at the college level, then became an attorney with higher aspirations. He organized several youth groups that he used to grandstand for political power; eventually he was disbarred (it is said because he became improperly involved with some of the youths from his groups.) Perhaps this is why he was given to the use of false names. At some fatal point he decided he could sing, and fancied himself a world expert on the true method of vocal production. He careened from one method to another, eventually returning to the Messa di Voce method with which he had started. Through all this he dragged poor Norma-Jean along with him.

They recorded several records similar to the Aida one presented here, all demonstrations of proper vocal method, and all available for $5.95 each. Discounts were offered for bulk sales, and as the liner notes state, “The price of this record is very reasonable when one thinks of the instructional saving it will be to both the teacher and the student.” There must not have been too many bulk sales, for these are among the rarest of all operatic LP recordings.

La Norma-Jean’s last traced concert was in Carnegie Hall on April 25, 1954 as assisting artist to heldentenor Kenneth Lane, but she continued teaching and preaching vocal methods, reverting to proclaiming Messa di Voce at the end of her life.

SYLVIA SAWYER (ca. 1920–?)

10 AIDA: Excerpt from Act 4 (abridged for your enjoyment) (Verdi) [Italian]

Capitol P 8177/9, reissued on Allegro 1712/4, 1952

“...A genius that is far more elusive...”

Scant information is available for this mezzo-soprano, featured on three complete opera recordings (Aida, Trovatore and Ballo in Maschera) from the first days of LP records, for which she is said to have paid to participate. At least one of the original sessions was supervised by the well-known record producer and pirate, Edward J. Smith (1913–1984). A review of the Trovatore by John Briggs in the New York Times (Nov. 30, 1952), calling her “a light and somewhat colorless mezzo-soprano,” stated her “name and her pronunciation of Italian suggests an American background, but the most fervent chauvinist can hardly find her singing more than adequate.” The only other instance in which the Times mentioned her was on June 2, 1953; the night before she and baritone Court Fleming had appeared in Trovatore at Rome’s Teatro Eliseo, “the first time in many years that two American singers have appeared here.” There is one other Times mention that might refer to our Sylvia: listed under Business Proceedings for April 19, 1951 is a notice that a bankruptcy proceeding had been discharged for one Sylvia Sawyer Todd, of Crescent Street, Astoria…had she bankrupted the family paying for the recordings?

She came from Lima, Ohio. According to a blurb in the Musical Courier for October, 15, 1952, her teacher and musical adviser was Joseph Balestieri, and she sang Amneris in Milan at the Castello Sforzesco and other leading parts at Chieti. The following information is found on the sleeve-note for the Allegro issue of Aida: “The Amneris is the young American Sylvia Sawyer, who sang over a score of performances at the Teatro Eliseo in Rome during the 1952-53 season, which resulted in her being selected for this recording. Miss Sawyer was selected by Arthuro [sic] Rodzinski to sing in Prokofieff’s War and Peace at the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino in Florence, at the Italian premiere of the opera, and in addition she sang major parts in virtually every important Italian opera house.” The liner notes for the Trovatore state in addition that she has sung “...throughout the length and breadth of Italy, where she was acclaimed not only for her magnificent voice, but for the raging intensity and brilliance of her acting.”

The following philosophical essay on Sawyer was written especially for this issue by Edward Tapper, music critic for Boston’s Bay Windows:

Oi vay, morir mi sento!

It is unfortunate that no extensive biographical information is available concerning mezzo-soprano Sylvia Sawyer. Hearing her, any listener would be justifiably curious to know how she came to sound as she does. Like that of her contemporary Maria Callas, Sawyer’s discography is solely operatic. There are no Arie Antiche or German lieder —- no Christmas record (though her many fans dream of unearthing one). Like some voracious beast, her art appeared to have fed solely on the meaty repertoire of grand romantic Italian opera. Apparently she was a Verdi specialist, leaving us merely our own fantasy to dream of what she would have done to the music of other great operatic composers.

On experiencing the unique talent of La Sylvia, one may ponder why she chose to record only on minor record labels. Perhaps Sawyer shared the lamentable fate of Leyla Gencer (b. 1924), Magda Olivero (b. 1912) and Madame Petrova (heard next on this disc), being denied a substantial recording career solely by the existing contractual obligations the larger companies had made to more commercially marketable singers. It has been said that Sawyer’s recordings were “vanity” records, that she paid the performing forces of the Rome Opera to feature her in these ventures. Who could believe that (having listened to her sing) the Rome Opera would accept money to record her? Undoubtedly these were vicious rumors spread by rival divas envious of the charismatic American newcomer. More likely is it that she had gotten to where she was from exhaustive work under some of the more prominent batons in Europe.

However in a certain sense, it is all to the better that there are no definitive biographical facts on Sawyer, as it allows her art to speak for itself, and perpetuates the mystique of this legendary figure. For years, we acolytes have been tantalized by rumors and apocryphal stories: incidents such as the Capri walk-out, the lost BBC tapes, and her notorious master classes, in which the brutally frank diva was said to have advised a burgeoning mezzo to consider a career in the fast food industry. This is understandable though, for like most uniquely gifted singing-actors, Sawyer would find it difficult to pass her art on to her pupils. The excerpt included here attests to this.

The Sawyer Amneris displays the singer at the pinnacle of her vocal powers. I shan’t waste time with superlatives, or take up space in discussing technical matters, such as the evenness of the voice, the density of the sound, or the accuracy of the high notes. Unlike other artists represented here, Sawyer possesses a genius that is far more elusive; it is difficult to pinpoint its source, and for many listeners, it is all but imperceptible, even after being subjected to frequent hearings. Above all, it is characterized by her level of comfort with the idiom, and her uncanny ability to bend the Italian language to her intense dramatic instincts. The artful “throwing off” of the aspirated “t” in the word “gettai” is but one ingenious stroke in a keen psychological portrait of the desperate, troubled Egyptian, a portrayal which at the same time smolders with dramatic urgency and pathos; indeed, it may safely be said that Sawyer’s is the most pathetic Amneris on record.

VASSILKA PETROVA (ca. 1914–?)

11 TOSCA: Abridged for your enjoyment (Puccini) [Italian]

Remington RLP 199 62, ca. 1951. Orchestra of the Maggio Fiorentino, Emidio Tieri, conductor.

“...The udder ten perzent know too damn much!”

“...what makes this set the Tosca from Hell, how ever, is the Floria of Vassilka Petrova, which has enjoyed some status as a camp artifact. It’s astonishing!” Conrad L. Osborn in the Metropolitan Opera Guide to Recorded Opera.

According to the sleeve note on her aria LP, Vassilka Petrova sang Salome, Elektra, and Aida, as well as Don Giovanni; (just where she sang them is not mentioned.) It states she was “Bulgarian born...a fine voice...developed through study in Milan, Paris, Vienna and New York... and a great personality...melded into one artist...add to these two qualities a vibrant, attractive personal appearance and an exquisite dramatic sense and you have an impresario’s dream. And just such an artist is Madame Vassilka Petrova...When you hear Madame Petrova’s amazing versatility...you will realize that here indeed is a remarkable artist...Madame Petrova becomes something of a phenomenon...you will enjoy Petrova...not for just a year or two, but for as long as you wish.” Which of us listeners would dare refute these observations?

Petrova’s discography includes a Cavalleria and a Tosca on the Remington label, and a Trovatore as well as excerpts from Aida and a recital disc on the Ace label. The Ace issues are also among the rarest of operatic LP records, and perhaps this is as it should be. Again, not a lot is known about her. It was said by a few wicked tongues that she wasn’t really Bulgarian at all, but only claimed she was, hoping to capitalize on the great popularity of the other, famous Bulgarian opera artists of her day. She was reputed to have been the wife of Remington Records owner and operator, Donald Gabor; others claimed she was married to America’s most successful fur importer. The same Edward J. Smith (who was associated during his career with so much that was questionable in singing) also supervised some of Petrova’s recordings. He later regaled friends with anecdotes of how he had to warn the other singers in advance not to betray unworthy feelings when they would first hear her at the sessions, since she was paying for them. The Amneris on the disc of Aida excepts, Elizabeth Wysor, was Smith’s first wife.

In fact, La Vassilka had a total of six husbands, the first a Russian; her penultimate was an explorer and author with the improbable name of Le Grand Cannon Griswold. He was familiarly known as “Sonny” and was a well-known figure in New York’s highest social circles. Her last was a movie producer, Allan D. Dowling, whose brother Robert Whittle Dowling owned most of the City Investing Company, one of the country’s largest real estate concerns. Their father had come to California from Ireland and struck it rich in the gold rush; the family was exceedingly wealthy and fashionable, and money and connections helped launch her singing career. She bought her way into a performance of Cavalleria Rusticana at the Brooklyn Academy, then had her Santuzza recorded in Italy and took the tape to Remington Records, which issued it. Next they issued her Tosca which received bad reviews. Tenor Eddy Ruhl (b. 1917), who was her Cavaradossi and Turiddu (and apparently one of her lovers), remembers walking with the Diva past Macy’s window, where they saw a display made up of copies of their recently-released Tosca. He talked to her of the bad reviews and tried to dissuade her from issuing further recordings until “she learned to sing better.” Ruhl performs a delicious imitation of her reply, spoken with a thick Bulgarian accent: “Oh Edd-dee, ninedy perzent of da people don’t know da difference, and da udder ten perzent know too damn much!” Ruhl last spoke to her some years ago via long distance to Monte Carlo where she had retired.

The discs of the PetrovAida and the PeTrovaTore contain tones that would thoroughly amaze even Conrad L. Osborn, but we have chosen to issue this tiny abridgement of the complete Petrova Tosca because of its hellish intensity, which is probably what Maestro Osborn was referring to in his observation.

MARI LYN (1907–1989)

12 THE BARBER OF SAVILLE: Una voce poco fa (Rossini) [Italian]

(Introductory remarks by Mme. Lyn)

1984, instrumental quartet.

“Here it is as it once was in all of its former, ornamented, over-cadenzorized glory!”

MARI LYN’S DREAM

Once not too long ago in New York there was a fat and untalented widow with a heavy Queens accent named Marilyn Sussman, who lived in the Murray Hill section with her eight dogs. She was short, she was old, she was ordinary and totally undistinguished but for one precious quality—she could dream. And dream she did—she imagined that she was tall, that she was glamorous and that she was an adored opera diva with a history of respected performances and a repertory that ranged from Christian hymns to Norma. Her husband had been a successful producer of a very popular television soap opera. When he died, he presumably left her able to indulge her dreams. Then in January 1984 local aficionados were startled by the unheralded appearance each Monday at 6 PM on public access cable TV of a new program entitled The Golden Treasury of Song. The show was obviously devised to launch a new star, a most unusual woman who performed under the name Mari Lyn. Marilyn Sussman had been reborn.

At least seven of these Monday evening extravaganzas, with titles like “Operetta Fantasy,” Nostalgia al Fresco” and “The South—Anti-Bellum Era,” were broadcast. Mme. Lyn wore the same blonde wig in each succeeding program, but styled differently and ever more extravagantly. And her gowns! No one who saw these programs could ever forget the sight of that dumpy body stuffed into her homemade frocks, each carefully fashioned as another fantasy. There was the clinging blue gown with stomacher that emphasized her enormous lower half, the gold lamé number with sequins and a plunging neckline for which she was five decades too late, and a tight black shift with open neckline crisscrossed with “dear slayer” stringing, among several others.

Obviously some capital was expended to introduce Madame Lyn to the world. Advertisements were taken in trade journals, and the February 20, 1984 issue of Show Business carried a full-page ad extolling her. The details of her biography listed there are astonishing, and one does not need to be an operatic historian to realize that they are entirely made up: her debut at seventeen with the Philadelphia La Scala Opera Company as Nedda, her contract with the Chicago Lyric Opera under Pietro and Gaetano Merola, the bus and truck tour across the country with the George Wagner Company, and the claim that “As a child protégé, she was a sensation at Madame Frances Alda’s swanky opera soirees presided over by the Russian prince Alexis Orloff at the Waldorf Astoria Towers.” Perhaps in deference to the hefty sum the ad must have cost, the editors saw fit to feature Madame Lyn on the cover as well.

Almost unbelievably, she also actually counterfeited four LP records on which she was the star. They appeared on the “Philips” label, and she went to the trouble to have Philips’s graphics and designs copied meticulously. The first issue was a single disc with her singing over a pre-taped orchestra from a Music-Minus-One record; the second was a three LP set made up of arias and songs taken from her video presentations. A favorite touch is the gold sticker proclaiming “Grand Prix – Academie du Disque Francaise.” The many photos of her carried on the record jackets must have made a small fortune for some lucky airbrush artist.

But it was her affect that thrilled her audiences the most – nothing, but nothing perturbed her and got through the lacquered shell of the persona she had created. Her appearance, her reading of the lines so carefully scripted, her singing—all were of a piece. In the program entitled “Hosanna at Ebentide,” after singing a group six hymns, she raised her pudgy arms to heaven at the words “Ho – zahn –nah, lord!” with almost indescribable lack of personality, and was “interrupted” by the arrival of a couple who identify themselves as representatives of the Della Rosa Foundation of Palermo, Sicily. They present her with an enormous trophy as “the best new operatic voice of the year.” She feigns surprise and then reads a few words of thanks from her prepared script, “I want to ….[pauses to turn page] thank you for this magnificent surprise….”..etc. It is perhaps the most magnificent example of her art captured on film, her very unawareness of the huge effect she is producing somehow humbling.

We have retained her commentary to give you the flavor of her unique personality. She tells the audience she will sing the aria “..just the way it was written...sung to the best of my ability within the limits of a dramatic soprano voice...here it is as it once was in all of its former, ornamented, over-cadenzorized glory.”

SARI BUNCHUK WONTNER (ca. 1935–1981)

13 LA TRAVIATA: Ah fors e lui; Sempre libera (Verdi) [Italian]

1980, orchestra and conductor unknown

“...Music lessons lead to licentiousness...”

In many ways Sari Bunchuk Wontner’s art more fully embodies the characteristic qualities of dedication and obsession than any other of our divas. We feel a particular obligation to include La Sari’s unique perspectives on tone, pronunciation and especially, rhythm. Wontner’s father Yascha Bunchuk had been a minor conductor of mixed parentage in Czarist Moscow, who had been selected by the composer to lead the Hungarian premiere of Myaskovsky’s Alastor, but had to cancel because of illness. He ultimately resettled in Hungary.

Her colorful Magyar mother was a talented student of the great Sari Barabas (b. 1918), but apparently never sang in public. Little Sari Bunchuk was entranced by her mother’s vocalizations but neither parent would hear of her studying music, her mother stating that music lessons lead to licentiousness and her father that she had no talent. She remained undeterred. When still young, Sari married Alastair Wontner, a rich London-born businessman. Financially able then to indulge her obsession with singing and especially the supposed parallels between her own life and Verdi’s La Traviata, she taught herself the title role in that opera. It is said that she performed Violetta several times over the years at private gatherings held most often in the immense music studio of their home in Las Vegas, Nevada. These were staged presentations with full casts and orchestra. A friend of Mr. Wontner’s surreptitiously recorded this glimpse on a crude hidden cassette recorder. It was her last Traviata before her own tragic end, falling overboard the Wontner yacht in the Caribbean.

TRYPHOSA BATES-BATCHELLER:

14 Darling Nelly Gray (Hanby) [English]

Melotone 314, ca. 1945, accompanist unknown

And, like a refreshing breeze after the heavy ill-winds of verismo, comes the simple pleasure of the American folk song.

FLORENCE FOSTER JENKINS (1868–1944)

1 Valse Caressante “Written for Mme. Jenkins” (McMoon) [English]

Melotone unnumbered, Matrix unknown 1941

Louis Alberghini, flute obbligato;

Cosme McMoon, piano

“…he is the common-law widow of the noted hog-calleratura….”

Florence Foster Jenkins is one of the most famous singers who ever recorded. Some of that fame derives from an affectionate essay written about her by the Metropolitan Opera’s Francis Robinson, who painted a picture of a slightly batty but charming dowager. This idea reached its apogee in an article by Daniel Dixon in the December, 1957 Coronet magazine: “There was a quaint nobility about this woman that quelled derision and softened ridicule…Neither she nor the vision to which she clung could be squelched. More than anything else, it was this that moved the sympathy and stirred the understanding of her listeners. She became the comic symbol of the longing for grace and beauty that is in some way shared by everyone who is clumsy and shy and ill-favored…an eloquent lesson in fidelity and courage.” Alas, like so much that has been written of musical history, this is at best incomplete and misleading, and at worst, untrue.

Jenkins was a monster of vanity and selfishness, but not crazy. She was cheap, secretive, superstitious, mean, dowdy and a snob, with an ego comparable to the greatest divas. She loved drinking manhattans and dyed her hair blonde into her seventies, and had a young paramour she kept hidden in a love nest. These and other details about her have been scarce before this.

Born in 1868 in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania to a well-off family, she had mechanical dexterity at the piano and was a kind of prodigy. At the age of ten she was appearing in public as “Little Miss Foster.” She graduated from the Philadelphia Musical Academy and Hale Dramatic School, and had also studied at A.M. Virgil’s school with Henry Gaines, and at the Hahn Dramatic School. Twice she was solo pianist with the Sagafests, through which she performed at the White House. By the time she died she had studied privately with Madame Fila Morin, Richard Hageman, John Hutchins, Sergei Tubinsky, Savatore Avatabile and others. At the age of seventeen she decided she wanted to go abroad to study music professionally, but her father wouldn’t hear of it. She eloped with a young doctor named Frank Thornton Jenkins of Washington, D.C., living with him in Philadelphia. Her father disowned her.

The marriage was unhappy and she separated from Jenkins when she discovered he had given her syphilis. There were some years of near poverty when she eked out a living as a piano teacher in Philadelphia, and in1902 she divorced Jenkins and came to New York. In 1909 her father died, and despite their differences, he left Florence an income, with the proviso that it be revoked if ever she married again. Her mother had inherited the bulk of the family fortune and promptly moved to New York, living for many months each year at the old Waldorf-Astoria, to be with Florence, and enjoy a life of independence and means. Earlier in 1909 Florence had met a handsome young actor twenty-two years her junior named St. Clair Bayfield (real name “Roberts”), and by August they were living “in sin” together. Earlier Florence had to give up the piano because of an accident to her arm, so all the while she had been taking voice lessons, making her first public appearance as a vocalist in 1912. She practiced every day, and after she was famous often told journalists that she coached regularly with a great singer from the Metropolitan Opera, but would never reveal the name. It was mezzo Henriette Wakefield (1879-1975.)

Her mother became quite a club woman, and was a member of forty-two different clubs in New York and other fashionable places, including the Daughters of the American Revolution and the like. Apparently she was something of a painter as well. Florence of course attended club affairs with her mum, and in 1916 was asked to be Chairperson of the opera and tableaux-vivant committee for the Euterpe Club. This set the stamp for the rest of her life. A year later she started her own club named The Verdi Club, and a list of members was quickly subscribed. She was now free to arrange club presentations without interference. At first these followed the conventional lines of the other clubs – there were dinners and luncheons and an annual “Rose Breakfast,” all with musical presentations with aspiring young artists presented in concert, and once a year, a complete Verdi opera was presented in semi-staged form.

The real fun for Florence and the others were the presentations of tableaux-vivants. Typically, the theme would be of the ilk of “A Dream of Fair Women,” and the various society women then would appear portraying such heroines as Cleopatra and Fair Rosamond. One woman who attended said later “…all these big women and they all had these chiffon trousers...I think that was the worst thing I ever saw, I think that was really the end of everything.”

Gradually Jenkins’s participation assumed star proportions. At the March 19, 1924, seventh annual Verdi Club Ball at Waldorf-Astoria ballroom, Marion Talley sang two arias. According to a press report, “after a few moment’s wait there appeared, standing on the stage rocks, the imposing figure of President Florence Foster Jenkins as Brünhilde, with shining silver spear, shield of gold, and white robe, with the big helmet hat. Loud applause and bravos caused the curtain to show her thus posed some six times…”

Florence developed a passion for exhibiting herself in outlandish costumes. She never sang in the Verdi Club presentations, but devised ever more outrageous pageants at which she and her club women friends could disport themselves, impersonating the great seductresses and queens and heroines of history and myth, as well as shepherdesses. Most of these wealthy women belonged to dozens of clubs, as did Florence and her mother, and Florence did sing regularly at many of them. By the late 1920s she had a circuit, with annual appearances in Philadelphia, Washington, Newport and other cities, and several appearance each year in New York. The highlight of her season was her annual recital at the Ritz Carlton Hotel ballroom. Society was perhaps more polite then, and the reviews were mostly of the double meaning type: “The general opinion of Florence Foster Jenkins was that she had never sung better.” Only occasionally would a review appear that suggested something worse: “...Mrs. Jenkins appeared in flame-colored velvet, with yellow ringlets piled high on her head. For a starter she picked Brahms Die Mainacht, subtitled on her gilt program as ‘Oh singer, if thou canst not dream, leave this song unsung.’ Mrs. Jenkins could dream, if she could not sing.”

By 1930 she was known as “The Singing President,” although she preferred for friends and acquaintances to call her “Lady Florence.” Her repertoire was enormous, ranging from Caccini, Jomelli, Bach through Handel, Haydn’s Creation, Mozart, all the way to Liszt, Rachmaninoff, Zerbinetta’s aria and de Falla songs. On October 29, 1930, her recital at Ritz Carlton was attended by more than three hundred persons. She sang Ravel’s La Flûte Enchantée, a Debussy Romance, Delibes’s Les Filles de Cadix. Elsa’s Traum from Lohengrin, Manning’s Luxemburg Gardens, Cui’s Statue at Czarskoye Selo, Baine’s Cherry Tree, Gounod’s Valse from Romeo and Juliet, Worth’s Midwinter, two Wolf songs, and Cosme McMoon’s Alborada, which was written for her, and performed “with action,” the composer at the piano. A final encore was Musetta’s Waltz from La Boheme. Edwin McArthur (1907–1987) played skillful accompaniments; Cosme McMoon played solos including the Liszt Rakoczy March.

Lady Florence had met McArthur two years earlier at a Barbizon Club musicale. She was impressed by his playing, and asked him to come for an interview. “Her suite was filled with an assortment of bric-a-brac such as you’ve never seen …pictures of herself in various poses, statuettes, lamps of all description, photographs of artists she knew. And she knew everybody.” (Opera News, March 16, 1963). McArthur later told friends that she had been deadly serious about her singing. At the interview she told him she wanted an accompanist who would not detract from her in any way during their performances, and therefore she required her accompanist to sit behind a folding screen on stage [one assumes this cut down on razor-sharp ensemble.] She hired him and they worked together for six years. Someone later convinced her to jettison the folding screen so the sound would be better. The association ended in a quaint fashion. At one concert McArthur inadvertently got a laugh when he smiled broadly at the audience as he came under the lights while walking out to the stage behind Madame. Liking the reaction, he tried this again at the next concert, but she was not amused; she fired him from the stage, apparently in full view of the audience at the Ritz Carlton Hotel. She told friends he looked like a “hemoglobin.”

This was the chance for which McMoon had been waiting. For years the aspiring composer-pianist had been hanging around, obsequious to Madame Jenkins to a fault, composing trifling salon works for her to sing, and generally insinuating himself into her life. Now he took over where McArthur was forced to leave off. At first he behaved himself and one paper reported that he was the only one of the twenty or so accompanists that Madame had tried who could keep a straight face. But this didn’t last long, and soon he was openly making fun of her during the concerts, alternately laughing with the audience and then jumping, extravagantly kneeling before her and kissing her hand after a particular musical disaster.

In the late 1950s a group of friends who had been associates of Florence Foster Jenkins were taped reminiscing about her. Kay Bayfield, who ended up marrying St. Clair Bayfied after Lady Florence’s death, said “…she was always cheese paring and if she could get someone else to pay for the taxi, she would.” Florence Darnault, the sculptress who had made the bust of Verdi used at the club, agreed: “…She was very careful about spending…. She’d ask me to come to lunch, but she never paid, never. She had asked me to lunch one day, and we had lunch in a very nice restaurant in a very good hotel…. And then, she got a phone call, and she went to answer the phone. She sent the bellboy back saying she just had to rush… and she left me with the bill …she made me buy four tickets for one of her events, before sticking me with the bill… She got ‘em out of her pocketbook and said, ‘You must take four tickets for this..’ And I paid for them…” Darnault then spoke of McMoon: “...he was a robber, you know. I thought it was terrible—he was paid as an accompanist and then he laughed while he played the accompaniments… and said, ‘now, lo!, what’s coming!’ and he’d wink at the audience. He lived on her, she gave him everything.” Adolf Politz, who had appeared in male roles in some of the tableaux, said: “ Cosme McMoon played for her on all the records and her last recital—she was very unhappy with him but it was too late to do anything about it, even though she had it in mind to fire him… he was a rotter through and through..”

Her notoriety increased year by year until 1941, when Lady Florence took a step that made her immortal. She went to a vanity-recording outfit, Melotone Records, and cut several sides. On June 16, 1941 Time magazine reviewed her recording of “Die Holle Rache,” comparing her repeated staccato notes to “a cuckoo in its cups.” According to the Coronet article, “‘Rehearsals, the niceties of pitch and volume, considerations of acoustics – all,’ wrote an official of the recording company, ‘were thrust aside by her with ease and authority. She simply sang and the disc recorded.’ More often than not, she would pronounce the first rough test of a song to be ‘excellent – virtually beyond improvement’ …Only once did she betray any misgivings… she phoned on the day following a session to say that she felt a trifle worried about ‘a note’ at the end of an aria from The Magic Flute by Mozart. But the Melotone Studio’s director Mera M. Weinstock gracefully quieted her fears. ‘My dear Madame Jenkins,’ she said, ‘you need feel no anxiety about any single note.’ She didn’t. She had a superb faith in her destiny as a diva – a faith so staunch and unswerving that it plugged her ears to the sour notes of the truth. Shyly, but firmly, she informed a Melotone executive that she had listened to a certain aria from The Magic Flute as recorded by famed prima donnas Hempel and Tetrazzini and that her rendition was ‘beyond doubt the most outstanding of the three.’”

Jenkins was a great snob, early in her career writing to the violinist who assisted in her concerts that “Madame Melba is the inferior of we two in that she is less discriminating in her choice of audiences.” This became a moot point on October 25, 1944, when Jenkins rented Carnegie Hall for her only appearance there. It was a sell out and journalists estimated that she pocketed $4,000 in profit. The reviews were mixed, some the usual double speak, but several were hostile. Isabel Morse Jones in the Los Angeles Times wrote: “I watched this indefatigable old lady, decked out in pink brocade and ostrich plumes…She was barely able to make it across the stage but once she was there and the accompanist had stifled his grins and begun the preparation for her entry into song, she launched into the most pathetic exhibition of vanity I have ever seen….When she began to sing folk music in costume, I left. There was something indecent and barbarously cruel about this business.”

Opinion is divided about her own reaction. Many friends said she never knew the difference and was happy with the results. Her boy toy St. Clair Bayfield claimed otherwise, saying the bad reviews had at last caused the scales to drop from her eyes, and her heart was broken. “…I didn’t want her to sing after her voice was worn out. But she was adamant. ‘I can do it,’ she told me. ‘I’ll show everybody.’ Florence was advised by people who desired personal profit… Well, it turned out the fiasco I expected. Afterwards, when we went home, Florence was upset – and when she read the reviews, crushed. She had not known, you see.”

Whatever the case, she was dead from a heart attack a few weeks later. There were a lot of strange difficulties associated with the wake and the burial through the Frank Campbell home—the coffin was wrapped in floral print cotton and looked very cheap. She was laid to rest at the family mausoleum in Wilkes-Barre.

Fighting erupted almost immediately about who was to get what. Jenkins had always carried two attaché cases; she told associates that because of her distrust of lawyers, she carried her will and important papers with her. The will was never found. Speculation was that McMoon had stolen it during her final illness, and later destroyed it. Sixteen distant cousins claimed her estate. The May 6, 1945 Sunday Mirror reported from “…New York Surrogate’s Court, where one St. Clair Bayfield, described as a retired Shakespearian actor and opera baritone, has asserted that he is the common-law widow of the noted hog-calleratura and No. 1 claimant of her $100,000 estate…” McMoon also brought suit, claiming that he had been Lady Florence’s lover, and that she had promised to set him up after her death. This infuriated all her acquaintances, who had known McMoon as someone who was “light in his loafers.” Bayfield produced over five hundred letters between himself and Lady Florence, and many of her friends testified on Bayfield’s behalf. He was awarded a sum, but the bulk of the estate went to the cousins. McMoon received nothing. Florence Darnault met him at the Hotel Pierre years later. She reminisced: “…there was Cosme McMoon and he came up to me and said, ‘You know, I’m a communist!’ …he was on the red velvet carpet amid all the ladies in jewels, the most sumptuous spot—I said this is a rather funny place to find a Communist.”

The remaining question about Lady Florence is, could she have always sounded like her records? Her voice must certainly have deteriorated considerably by the time she recorded at the age of seventy-three, but apparently it was never more than “a squeak.” And experience tells us that musical people do not become less musical as they age.

One minor matter must be addressed: the correct speeds of the Jenkins records, and thus the proper pitches of her performances, are in some dispute. There are those who feel that she transposed down a lot, and that the records have to be played at speeds slower than 78 rpm in order to reveal the rich, baritonal timbre of her instrument. To them we say, “Bah!” The glory of her high notes—the incredibly clear and intense “A” that ends McMoon’s “Valse Caressante” cannot be ignored. The focus of her “E” vowels alone disproves these arrivistes and soi disant experts.

16 Cosme McMoon reminisces about Florence Foster Jenkins

ca. 1954.

What with his improbable and mirth-provoking name, Cosme McMoon emerged from his association with Foster Jenkins as a minor celebrity in his own right. He was born on February 21, 1901 in Texas and studied entirely with teachers there, then began playing in modest venues around the country. The January 17, 1920 issue of Musical America states that McMoon was one of four finalists in a piano competition for which Rachmaninoff was the judge; Cosme did not win. In February 1925 his playing was broadcast on New York’s WFBH, and about that time he cut at least two ArtEcho piano rolls (his own “Dolores” and Albeniz’s “Cadiz”). The New York Times reported that his first recital there happened at Town Hall on March 22, 1936. The review stated that Beethoven’s Op. 111 sonata was “perhaps too ambitious an undertaking.” A photo appearing on the day of the recital shows a thin, handsome, even aristocratic face. Two other New York recitals in 1937 and 1939 were reviewed in the Times, his performances found to be “straightforward,” with his tone becoming harsh at top volume and his technique not up to the hardest spots of the Liszt Sonata.

McMoon’s story of Mme. Jenkins’s plans for a musical foundation with him at the helm is highly suspect. His character does seem to have been unsavory. In his old age he was a constant feature, hanging around a particular gym on Manhattan’s West 42nd Street that was frequented by bodybuilders. McMoon and other men would importune the weight lifters to accept honorariums for sexual favors. This intercourse eventually blossomed and led to McMoon’s change of career, when he became co-manager of a male bordello located in the same building as the gym. He died in August, 1980.

Notes on the performers by Gregor Benko