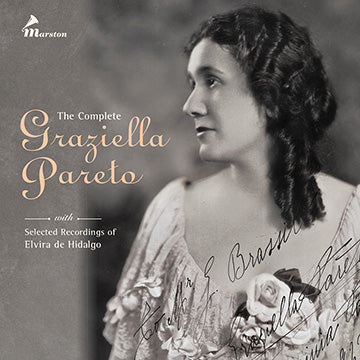

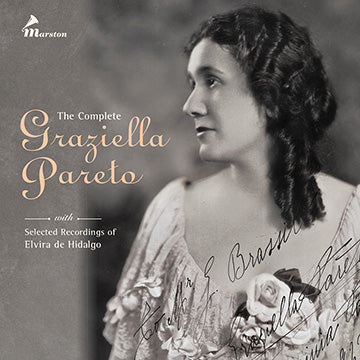

Graziella Pareto (Barcelona, 6 May 1889 – Rome, 1 September 1973) made her operatic debut as Micaëla in Carmen, on the 8th of May 1906, at the Teatro Liceu, Barcelona. By age twenty-one she was singing with the biggest operatic stars of her time. Step by step she conquered all the major opera houses in Spain and Italy, toured all over the world, and never had to perform in less important theaters.

Most critics described Pareto’s singing as “exquisite,” “artistic,” “aristocratic,” and “elegant.” Others felt she had “a light voice” which occasionally got “drowned by the orchestra except for the high notes,” which may explain why her on-stage stardom was not achieved. Her recorded legacy, however, though relatively small, for the most part overcomes the problems of projection. Even before her second operatic engagement, the Milan branch of the Gramophone Company contracted Pareto (on the 25th of September 1907) to make celebrity red label records. Recording exclusively for the Gramophone Company, Pareto transmits her artistic and aristocratic style through the grooves. In addition, one hears flawless technique, beauty of voice, evenness of her registers, and clarity. Pareto was an incomparable artist and we are proud to release all thirty-six sides she made.

Filling out this two-CD set are selected recordings of Elvira de Hidalgo. A student of Melchior Vidal (Pareto’s teacher as well). Hidalgo is best remembered as the teacher of Maria Callas, who spoke often and glowingly of Hidalgo. We have chosen eight selections, two of which were electrically recorded in Athens in 1933.

The set includes notes by Michael Aspinall and an abundance of photos.

CD 1 (73:58) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., MILAN, 1907 | ||

| Studio Orchestra, unidentified conductor | ||

| 1. | LA SONNAMBULA: Sovra il sen la man mi posa (Bellini) | 2:29 |

| 11099b (53521) | ||

| 2. | LA SONNAMBULA: Ah! non credea mirarti (Bellini) | 3:57 |

| 1401½c (053156) | ||

| 3. | LA SONNAMBULA: Ah! non giunge (Bellini) | 3:10 |

| 11100b (53522) | ||

| 4. | LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR: Quando rapito in estasi (Donizetti) | 3:49 |

| 1389c (053152) | ||

| 5. | LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR: Splendon le sacre faci [Mad Scene, part 1] (Donizetti) | 4:13 |

| 1390½c (053153) | ||

| 6. | LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR: Spargi d’amaro pianto [Mad Scene, part 2] (Donizetti) | 3:13 |

| 1391c (053154) | ||

| 7. | RIGOLETTO: Caro nome (Verdi) | 4:15 |

| 1369c (053151) | ||

| 8. | LAKMÉ: Où va la jeune Hindoue? (Dov’è l’indiana Bruna) [Bell Song] (Delibes) | 3:54 |

| 1402c (053157) | ||

| 9. | Frühlingsstimmen (Voci di primavera) (Johann Strauss Jr.) | 4:42 |

| 1400c (053155) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., MILAN, NOVEMBER 1908 | ||

| La Scala Orchestra, Carlo Sabajno conductor | ||

| 10. | DON GIOVANNI: Là ci darem la mano (Mozart) | 3:12 |

| with Titta Ruffo, baritone 21 November 1908; 2728f (054229) | ||

| 11. | RIGOLETTO: O mia Gilda … Lassù in cielo (Verdi) | 4:15 |

| with Titta Ruffo, baritone 23 November 1908; 2733f (054228) | ||

| 12. | CARMEN: Je dis que rien ne m’épouvante (Io dico, no, non son paurosa) (Bizet) | 4:25 |

| 18 November 1908; 2716f (053208) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., MILAN, JULY 1918 | ||

| Studio Orchestra, unidentified conductor | ||

| 13. | RIGOLETTO: Gualtier Maldè … Caro nome (Verdi) | 4:56 |

| 6 July 1918; 3283c (2-053172) | ||

| 14. | RIGOLETTO: Signor né principe … È il sol dell’anima (Verdi) | 4:47 |

| with Lamberto Bergamini, tenor 9 July 1918; 3285c (2-054079) | ||

| 15. | RIGOLETTO: Schiudete! Ire al carcere Monteron dee … Sì, vendetta! tremenda vendetta (Verdi) | 3:11 |

| with Matteo Dragoni, baritone 6 July 1918; 3281c (2-054080) | ||

| 16. | LA TRAVIATA: Libiam ne’ lieti calici [Brindisi] (Verdi) | 3:22 |

| with Lamberto Bergamini, tenor 6 July 1918; 3280c (2-054081) | ||

| 17. | LA TRAVIATA: Dite alla giovine (Verdi) | 4:37 |

| with Matteo Dragoni, baritone 6 July 1918; 3284c (2-054082) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., LONDON, MAY/JUNE 1920 | ||

| Studio orchestra, Percy Pitt, conductor | ||

| 18. | Il bacio (Arditi) | 4:14 |

| 29 May 1920; HO4415-2af (2-053179) | ||

| 19. | O bimba bimbetta (Sibella) | 3:15 |

| 10 June 1920; HO4432-1af (2-053174) | ||

Languages: | ||

CD 2 (78:22) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., LONDON, MAY/JUNE 1920 (continued) | ||

| Studio orchestra, Percy Pitt, conductor | ||

| 1. | LE NOZZE DI FIGARO: Giunse alfin il momento … Deh vieni non tardar (Mozart) | 4:03 |

| 10 June 1920; HO4430-2af (2-053176) | ||

| 2. | DON PASQUALE: Quel guardo il cavaliere … So anch’io la virtù magica (Donizetti) | 4:41 |

| 29 May 1920; HO4416-1af (2-053173) | ||

| 3. | LA TRAVIATA: È strano! È strano! … Ah, fors’è lui (Verdi) | 4:02 |

| 10 June 1920; HO4429-2af (2-053177) | ||

| 4. | LA TRAVIATA: Follie! Follie! … Sempre libera (Verdi) | 2:42 |

| 10 June 1920; HO4431-2af (2-053175) | ||

| 5. | LES PÊCHEURS DE PERLES: Comme autrefois dans la nuit sombre (Siccome un dì, caduto il sole) (Bizet) | 4:41 |

| 29 May 1920; HO4414-2af (2-053178) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., MILAN, MAY 1924 | ||

| Studio orchestra, unidentified conductor | ||

| 6. | LES PÊCHEURS DE PERLES: Ton coeur n’a pas compris le mien (Non hai compreso un cor fedel) (Bizet) | 4:10 |

| with Fernandino Ciniselli, tenor 15 May 1924; CK1482-1 (DB762) | ||

| 7. | LA SONNAMBULA: D’un pensiero e d’un accento (Bellini) | 4:27 |

| with Giovanni Manuritta, tenor 10 May 1924; CK1472-2 (DB762) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., BARCELONA, FEBRUARY 1926 | ||

| Frederico Longas, piano | ||

| 8. | Canço de Breçol (Longas) | 3:24 |

| 4 February 1926; BS2241-1 (DA775) | ||

| 9. | Pensant amb tu (Longas) | 2:05 |

| 4 February 1926; BS2242-1 (DA775) | ||

| 10. | Dolor de amar (Longas) | 2:20 |

| 4 February 1926; BS2243-1 (DA773) | ||

| 11. | Canço de Nadal (Catalan song) | 1:49 |

| 5 February 1926; BS2250-2 (DA781) | ||

| 12. | La pastoreta (Catalan song) | 1:14 |

| 13. | Canço de Nadal (Catalan song) | 1:49 |

| 5 February 1926; BS2250-2 (DA781) | ||

| 14. | L’hereu riera (Catalan song) | 1:07 |

| 15. | El bon caçador (Catalan song) | 1:21 |

| 6 February 1926; BS2251-1 (DA781) | ||

| 16. | Mi Niña (Guetary) | 2:22 |

| 5 February 1926; BS2252-1 (DA772) | ||

| 17. | La Guinda (Longas) | 2:19 |

| 6 February 1926; BS2258-1 (DA774) | ||

| 18. | La piel de mi amada (Longas) | 2:51 |

| 6 February 1926; BS2259-1 (DA773) | ||

| 19. | Estrellita (Ponce) | 2:38 |

| 6 February 1926; BS2260-1 (DA772) | ||

APPENDIX | ||

ELVIRA DE HIDALGO, Selected Recordings | ||

COLUMBIA PHONOGRAPH COMPANY, LONDON 1924 | ||

| Studio Orchestra, unidentified conductor | ||

| 20. | Clavelitos (Valverde) | 1:53 |

| 20 March 1924; A706 (3900-M) | ||

| 21. | EL NIÑO JUDÍO: De España vengo (Luna) | 3:24 |

| 20 March 1924; A707 (3900-M) | ||

| 22. | Tus ojillos negros (de Falla) | 3:27 |

| 20 March 1924; A712 (30025-D) | ||

| 23. | LAS HIJAS DE ZEBEDEO: Al pensar en el dueño (Chapí) | 2:23 |

| 20 March 1924; A711 (30025-D) | ||

| 24. | SADKO: Chanson Hindoue (Rimsky-Korsakov) | 2:58 |

| Summer 1924; A1284 (2035-M) | ||

| 25. | Solovey (El ruiseñor) (The nightingale) (Alyabev) | 3:29 |

| 20 March 1924; AX376 (8940-M) | ||

THE GRAMOPHONE COMPANY, LTD., ATHENS, 27 NOVEMBER 1933 | ||

| Studio Orchestra, unidentified conductor | ||

| 26. | Glikiá Tsigána (Traditional Spanish song?) | 2:53 |

| 0T1363-1 (AO2052) | ||

| 27. | CANCIÓN DEL OLVIDO: Canción del Olvido (Tragoudi tis Lismonias) (Serrano) | 2:48 |

| 0T1365-2 (AO2052) | ||

Languages: | ||

Producers: Ward Marston and Scott Kessler

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston, J. Richard Harris

Photos: Gregor Benko; Rudi van den Bulck/Charles Mintzer Archive; Peter Clark, Curator of the Metropolitan Opera Archive; and Michael Hardy

Booklet Coordinator: Mark S. Stehle

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Booklet Notes: Michael Aspinall

Marston would like to thank the following for making recordings available for the production of this set: Gregor Benko, John Bolig, Jeffrey Miller, and James Shulman.

Marston would like to thank Paul Steinson for providing a digital transfer of HMV matrix 053157 (CD 1/8).

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

GRAZIELLA PARETO

by Michael Aspinall, ©2022

Her career — “not far from sensational”

Paul R. Martin, Chicago Journal of Commerce, 14 July 1923

In his recently published book Tre Voci Catalane [Rome, Edizioni del TIMAClub, 2020], Maurizio Tiberi, who enjoyed the privilege of friendship with the singer in her declining years, has given us an exhaustive pen-portrait of Graziella Pareto, of whom the fastidious Sir Thomas Beecham wrote:

The quota of fine singers included a newcomer, who proved to be one of the most accomplished of our age, Graziella Pareto. Of slight and distinguished appearance, this remarkable artist had a voice of exquisite beauty, haunting pathos and flawless purity. Of the various roles she undertook, Leila in Les Pêcheurs de Perles and Violetta in La Traviata were the most outstanding, her representation of the latter being easily the most attractive and satisfying in my recollection. But like Claire Dux and a few others of exceptional merit, Pareto never achieved that pre-eminent position to which her gifts seemed to destin her, and though there is generally a reason for such things, in this case I am ignorant of it. [A Mingled Chime, London, Hutchinson, 1944]

Sir Thomas was recalling the Covent Garden season of 1920, on which occasion Pareto made some of her—alas!—few records, which fully explain and support the enthusiasm of the peppery Sir Thomas.

Engracia Enriqueta Angela Pareto i Homs was born in Barcelona on the 6th of May 1889, and died in Rome on the 1st of September 1973. Her mother, Angels Homs i Buqueras, was a zarzuela singer (who made a few records), her father a factory owner. His name, Pareto, seems to be of Italian and possibly Genoese origin. At the age of nine Graciela, as she was then called, was taken to hear her compatriot, the fifteen-year-old Maria Barrientos, in Dinorah, and was fired with the desire to be a singer. She studied for a few years with a lady named Caridad Hernandez (or, perhaps, de Herrera) before making a concert debut in her native city in 1906, singing the “Waltz Song” from Gounod’s Mireille. Antonio Bernis, impresario of the Teatro Liceu, Barcelona, was present, liked her, and engaged Pareto to make her operatic debut as Micaëla in Carmen, which she did on the 8th of May 1906. It is pleasant to read that her mother also sang a small part in this performance. So the lucky girl was launched in one of the most important theaters in Europe and never looked back: step by step she conquered all the major opera houses in Spain and Italy, and never had to perform in less important theaters. This first success induced a local Maecenas to persuade the impresario Camillo Bonetti to sign a contract with Pareto (or rather, with her mother, as Graciela was only seventeen) in which he advanced the necessary money for her further training. The choice of the tenor Melchior Vidal, then teaching in Milan, was a good one—his other pupils included Rosina Storchio, Lucrezia Bori, Esperanza Clasenti, Elvira de Hidalgo (who has lived longest in the popular memory for having taught Maria Callas), and Mercedes Llopart, who taught Elena Suliotis, Renata Scotto, Fiorenza Cossotto, Ivo Vinco, and Alfredo Kraus. However, even before her second operatic engagement, which was at the Teatro Real, Madrid in December 1907, the Milan branch of the Gramophone and Typewriter Co. contracted Pareto (on the 25th of September 1907) to make celebrity red label records! However had they come to hear of Pareto—could it have been through Maestro Vidal? It is likely that this was a sly move in a fight between Carlo Sabajno, the resident conductor for G&T in Milan, and Luisa Tetrazzini, the foremost “coloratura soprano” of the day. Tetrazzini had quarreled with the Maestro, who had been sent to arrange to make recordings of her in view of her impending Covent Garden debut, so the excitable and perhaps understandably offended Sabajno was looking for a serious rival to Tetrazzini for the red label catalogue. Subsequently the Milan branch deliberately delayed publication in Italy of Tetrazzini’s expensive pink label London records of December 1907, preferring to push the cheaper ones sung by the unknown Pareto.

Graciela duly sang La sonnambula in Madrid on the 25th of December 1907, with the tenor Umberto Macnez and the bass Francesco Navarini in the cast, followed by Lucia di Lammermoor and Rigoletto (with Giuseppe Anselmi, Titta Ruffo, and Navarini), after which she made her Italian debut—as Graziella Pareto—on the 8th of February 1908 at the Teatro Regio, Parma, in La sonnambula (again with Macnez). Back at the Liceu, Barcelona, she appeared with Ruffo in Thomas’s Amleto on the 19th of April, followed by Lucia di Lammermoor on the 26th. She returned to Madrid in December for Lucia di Lammermoor, Amleto (with Ruffo), and I puritani (which she never sang again), and on the 30th, her first Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia. She and Ruffo appeared together again in Rome at the Costanzi on the 13th of March in Amleto (for which Graziella had no orchestral rehearsal), then in April they journeyed on to the San Carlo, Naples for Amleto and Il barbiere. In Milan, on the 20th of April 1909, Graziella married the pianist, composer, and singing teacher Gabriele Sibella (1877–1925?), real name Alfonso Giacomo Sibella, whom she had met at Vidal’s studio, which Sibella took over on the Maestro’s death. She kept his enchanting song “O bimba bimbetta” in her repertoire for many years, but after Sibella accepted work in New York with the music publisher Schirmer in 1915, the couple seem to have drifted apart.

On the 25th of May 1909 Pareto made her debut at the Colón, Buenos Aires, in Rigoletto with Ruffo and Alessandro Bonci, conducted by Luigi Mancinelli, followed on the 8th of June by L’elisir d’amore boasting the dream cast of Pareto, Bonci, Giuseppe De Luca, and Antonio Pini-Corsi. Bonci and Ruffo accompanied her in Il barbiere and she was Ophelia again to Ruffo’s Hamlet. Returning to Europe, Pareto sang Rigoletto with Dmitri Smirnov and Ruffo at Monte Carlo on the 20th of February 1910, after which she was contracted to sing in St. Petersburg, but an unlucky fall suffered by her husband put an end to this visit. Her next engagement seems to have been back in Buenos Aires in May: Rigoletto and Il barbiere with Ruffo and Anselmi, Amleto with Ruffo. In September these operas were repeated in Montevideo, but here her tenor was Fernando Carpi. When she found herself back in Madrid in December her tenor was Macnez once more, her Rigoletto and her Figaro was Riccardo Stracciari; Il barbiere was conducted by Gino Marinuzzi.

Could she have been dazzled by all this? She was still only 21 and she was singing with the biggest stars of her time. In February and March 1911 she was in Valencia and at the Liceu, Barcelona, and then on the 16th of April she was back at the Costanzi, Rome in an all-star Barbiere: Pareto, Macnez, Ruffo, Giuseppe Kaschmann (Bartolo), and Nazzareno De Angelis (Basilio), conducted by Mancinelli. The magazine Orfeo praised her for singing “with a delicate voice and with admirable skill, earning universal and warm applause.” On the other hand, the critic of Musica was cooler: “Her voice is weak in the lower and medium registers, but rises securely to the high notes, is of good timbre, and daring in vocalized passages. The ingenuousness of her acting was almost constantly overdone and at certain points she became awkward and cold.” During this period she usually stopped the show in the lesson scene with Proch’s Variations. On the 31st of May she appeared in La sonnambula at the Teatro Bellini, Catania.

In September 1911 Pareto began a South American tour with Ruffo, singing in São Paolo and Rio de Janeiro, but went off on her own to Cuba, where she appeared in La sonnambula with the delightful tenor Giuseppe Paganelli in Havana on the 14th of December, followed by Rigoletto and Il barbiere. When an admiring Cuban journalist asked her where she had found the inspiration for her correct costume as Rosina, she replied “From Goya’s pictures, especially the one called El pelele.” In Havana on the 30th of December she added a new role to her repertoire, Norina in Don Pasquale. The company toured Cuba until the end of February 1912. Her next engagement was at the Népopera, Budapest in October 1912, where, in Rosina’s lesson scene, she sang “Voci di primavera” by Johann Strauss II, in which a critic revealed that her voice sounded clearer and more perfect than the flute that vied with her in the cadenza. In Budapest, “far from the madding crowd”, she tried out La traviata for the first time on the 18th of November. After conquering the Berlin Royal Opera in January1913 she appeared in Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette in Trieste, a flop according to Orfeo, but “Giulietta was Graziella Pareto, soprano leggero, who rejoices in excellent vocal resources that have been stupendously trained, and which she deploys with skill, though the voice is too slender and more adapted to the concert hall than to the theater.” She followed this by joining Giuseppe De Luca in Rigoletto, where she was able to bring the house down with her “Caro nome”, especially at the end with her spectacular ascent to the high E natural. Inspired by the fiery De Luca, she was able to rise to the occasion and her acting as well as her lovely singing was praised. In March she was in Odessa, singing with De Luca again in Rigoletto, Il barbiere, and Don Pasquale, and in April they were together in Kiev. On the 9th of May she was joined by Fernando Carpi, Mario Sammarco, Pompilio Malatesta, and Vanni-Marcoux in another all-star Barbiere at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, Paris. In September, after concerts with Alessandro Bonci in his hometown of Cesena, she was off to Stockholm and then Budapest again.

Pareto began the fateful year of 1914 with Il barbiere at the Teatro Regio, Turin, with Carpi and Stracciari, conducted by Ettore Panizza, followed by a round of familiar roles in Italian theaters, often accompanied by Fernando Carpi. Elvira de Hidalgo, her friend and fellow student of Maestro Vidal and the most famous Rosina of her day, had recently appeared at Turin in Il barbiere and comparisons were inevitable. The critic of La Gazzetta del Popolo was conquered:

With her tiny thread of a voice, sweet, sympathetic, modulated with consummate art, exquisitely emitted, at ease when ranging with all the security of the lark among the very highest notes, Pareto uses that voice like a great lady for whom art no longer has any secrets…. Simplicity taking the place of artificiality, that is Pareto’s fundamental note.

La Stampa also capitulated:

She had to undergo a stiff comparison. She faced the challenge, and won it through her gifts of a sweet voice, rich in delicate colorings, and trained to such an artistic conception of singing as to make her performance something serene, uplifting and aristocratic.

In her old age Pareto’s memory was unreliable, but on the subject of De Hidalgo’s Rosina she never forgot and would repeatedly relate that “Our Maestro had driven the score into her head note by note, for she was thick-headed … note by note … but it was useless, she didn’t understand anything.”

With the outbreak of war, Pareto, like many other star singers, found her excursions abroad more restricted but her career continued without serious interruption. She sang with Tito Schipa for the first time in La sonnambula at the Teatro Politeama, Genoa, on the 24th of October, both of them receiving rave reviews. On the 28th of December she arrived at La Scala, Milan in Rigoletto with Hipolito Lazaro and Carlo Galeffi, conducted by Marinuzzi. It is an amusing sign of the times that the critic of Corriere della Sera, after praising her fresh and lovely voice and her technical skill, reproved her for daring to introduce embellishments into “Caro nome”! On the 6th of February 1915 she introduced Lakmé into her repertoire at Madrid, adding Il barbiere with the faithful Carpi, then in March she sang with Enrico Caruso in Lucia di Lammermoor in Monte Carlo. From November she was busy touring Spain with Stracciari, singing her favorite roles in Palma de Mallorca, Valencia, Madrid, Saragoza, Bilbao, and San Sebastian. At the Liceu, Barcelona, in January 1916, she sang La traviata, Rigoletto, and Il barbiere with Mattia Battistini, following this on the 2nd of February with her first Susanna in the first ever performances of Le nozze di Figaro in Barcelona. In March she reappeared in Monte Carlo not only in La sonnambula, but even adding another two new roles to her repertoire: Carolina in Il matrimonio segreto (with Antonio Pini-Corsi as Geronimo) and Mimì in La bohème, a possibly dangerous experiment: in the event one review praised her “charm, melancholy, delicate touch, dreamy atmosphere”, all of which would have registered in that relatively intimate theater, but she wisely refrained from trying this predominantly lyrical role again. Her next important stop was at the Opéra-Comique, Paris, in October for two performances of Il barbiere with Stracciari and Vanni-Marcoux, which the same cast repeated at Lyon. She unveiled her Violetta in La traviata to Italian audiences in Genoa and Turin in November, then on December 26th she sang Lucia at the San Carlo, Naples, consolidating her triumph with performances of La sonnambula (in two of which she was joined by Schipa) in March 1917, cleverly reserving her Violetta for a later visit. After performances in Zürich in June–July 1917 she was Amina once more to Schipa’s Elvino at the Teatro Rossini, Venice,

Pareto began 1918 with a triumphal revival of La traviata at the San Carlo on

January 12th:

… as soon as the distinguished artist, so exquisitely dressed in the fashion of 1830, which made her look even more fragile and exquisite; as soon as she had delighted the audience with the joyous Brindisi, she immediately appeared completely involved in the spirit of the character … the Graziella Pareto whom we had previously only known as a magnificent jewel in the art of vocalization, was revealed and established as a dramatic soprano for whom no role is too arduous. [Armando Pappalardo in Don Marzio, 13th–14th January 1918.]

On the other hand, an anonymous clipping opines that: “She sang well, but was unable to make the scenic figure of Violetta stand out. She remains, therefore, an estimable singer. But not an interpreter. However, the audience applauded her warmly, and as a singer she deserved this.” The critic of Il Giorno was among those favorably impressed: “This exquisite singer always brings the most delicately sensitive touch to every interpretation. Last night everything she sang was full of poetic sweetness”, while the magazine Musica enthused: “The delicious artist gave an entirely personal imprint to the character, singing with passion, grace and elegance.”In February–March 1918 she returned to Monte Carlo, where the lucky subscribers heard her in Rigoletto and La traviata with Schipa and Battistini, and Lucia with Schipa. A historic occasion was the revival of Giovanni Paisiello’s Il barbiere di Siviglia on the 31st of March, with Schipa, Robert Couzinou, and Marcel Journet, conducted by Victor De Sabata. Her last wartime operatic appearances took place at the Politeama Chiarella, Turin, in April and June 1918: Il barbiere, La sonnambula and Lucia di Lammermoor. In July she was in Milan making new records for His Master’s Voice.

In December 1918 Pareto returned to Barcelona in Rigoletto (with Macnez) and Il barbiere (with Schipa), to which she added her first Zerlina in Don Giovanni (with Battistini). Beginning from 1919 she seems to have slowed down her appearances, her one operatic engagement that year being Il barbiere at the Vaudeville Lyrique, Paris on the 22nd of November, but a burst of international activity was shortly to follow. This began with Violetta in La traviata at the San Carlo, Naples, on the 2nd of March 1920, where she was heard by the influential “high society” soprano Marie Louise Edvina, who wrote to recommend her to Covent Garden, where she made her London debut on the 12th of May in Les pêcheurs de perles with Tom Burke and Ernesto Badini, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham. This was followed by Don Pasquale and La traviata. Sir Thomas’s enthusiasm was shared by many, if not by all: while the Daily Chronicle thought that in Les pêcheurs de perles she had a voice of lovely quality, a marvelous technique and an artistic style far above that of many coloratura sopranos, and that she would be followed with interest, the Times, in sour mood, declared her to be a disappointment, a light voice easily drowned by the orchestra except for the high notes. The Daily Express liked her, finding her one of the most fascinating artists heard and seen on this stage for years … to her refined musicianship she added a delightful personality and a winning presence. Her gestures, her movements were the quintessence of grace and “Pareto nights” might well be all the rage in the next few weeks. The Observer found that her voice sounded much more impressive in Don Pasquale and that her florid execution was brilliant. Her Violetta in La traviata seems to have won more general approval, despite still vivid memories of Tetrazzini. The Daily Chronicle praised:

… the very delightful singing and acting of Mlle. Graziella Pareto as Violetta …. Verdi’s familiar work gave her more scope to show her powers, and her performance was one of the best seen and heard for a long time at Covent Garden. Her singing of “Ah, fors’è lui” was brilliant, and in the duet with Alfredo Mlle. Pareto also sang charmingly, and made Violetta’s death in the last act unusually effective.

Even The Times was impressed: “She sang with her face and hands and acted with her voice; and it is the power of doing this that alone can cheat us into the belief that opera is a higher form of art than either the stage or the symphony”. Most interestingly of all, the anonymous critic of The Athenaeum compared her to Gemma Bellincioni, who he had heard at Covent Garden in 1895. Pareto, he found, was very far from being a second Bellincioni, who, however, might well have been her model, but certainly it was many years since a Traviata of such exquisite appearance and of so fascinating a personality had been seen on the Covent Garden stage. Her singing had been a delight to the ear, though he found her falling short of the vivacity and brilliance needed for the first act, and while she had been admirable in the pathos of the later scenes she had altogether failed to seize the opportunity offered by the tremendous explosion of feeling that is the “Amami Alfredo” in Act Two.

This successful Covent Garden season won Pareto a tour of the British Provinces between the 7th of November and 16th of December 1920, visiting seventeen cities plus two Albert Hall concerts. This was a tastefully organized tour with such top rank assisting artists as the baritone Dinh Gilly, the violinist Yovanovitch Bratza and the pianist Claudio Arrau. She shared a concert at the Royal Albert Hall on the 21st of November 1920 with Dame Clara Butt! After a concert in Leicester on the 16th of December, her next appearances were in March 1921 in Monte Carlo, where she sang, for the first time, the Queen of the Night in Il flauto magico with John McCormack as Tamino, and he was also her Almaviva in Il barbiere. (Pareto had been singing the Queen’s second aria, “Gli angui d’inferno”, in concerts for years.) It will be seen that her appearances were becoming more widely spaced apart, for we next hear of her participating in the celebration of the one-hundredth anniversary of the independence of Mexico. The Mexico City opera season opened at the Teatro Arbeu on the 17th of September 1921 with La traviata, Aureliano Pertile alternating with Schipa as Alfredo. This was followed by Mignon with Schipa, in which Ofelia Nieto sang the title role and Pareto was Filina, then came Rigoletto with Schipa and Carlo Galeffi.

It was towards the end of her heyday that Pareto finally arrived in the United States, engaged by the prestigious Chicago Opera Company, second only in importance to the Metropolitan of New York. She made her first appearance in La traviata with Tito Schipa and Josef Schwarz—typically luxurious casting by the Chicago company—at the Manhattan Opera House, New York, on the 24th of January 1922. In The New York Herald the dean of American music critics, W. J. Henderson, greeted her fairly warmly, describing her as tall and pleasing to look at, judging her voice small, but of better quality than that of Barrientos; the scale was properly equalized with no problems in the passaggio, but he found her high notes thin, metallic and compressed. Miss Pareto was gracious and moved onstage with decorum, and he decided that on the whole her performance was that of an experienced artist who had carefully prepared a task for which her resources were scarcely sufficient. Others were more ecstatic, the author of an anonymous clipping suggesting that Miss Pareto had greatly exceeded the audience’s expectations. Her voice was neither big nor brilliant, but was exceptionally pleasing, with the soft gleam of a pearl in every note throughout the well equalized scale. Her intonation he found faultless, and the florid passages in “Ah, fors’è lui” and “Sempre libera” were impeccably sung, even though dazzling bravura was not hers to offer. She sang Lucia di Lammermoor with Tito Schipa at the Manhattan on the 20th of February, then after concerts in New York and Brooklyn she moved on to Chicago, where she was welcomed with great enthusiasm in La traviata at Ravinia Park on the 27th of June, followed by Lucia di Lammermoor (with Schipa) on the 2nd of July and Rigoletto on the 9th. As usual, she did not make any extraordinary hit as Adina in L’elisir d’amore on the 21st (“more at her ease playing a great lady than a village maiden”), but her first Micaëla in Carmen since her debut in 1906, on the 22nd of July, must have been very appealing. After Il barbiere Pareto added another new role, Susanna in Wolf Ferrari’s Il segreto di Susanna, making an enchanting couple with the baritone Vicente Ballester, and finishing her first Ravinia Park season with Lakmé (singing in Italian while the rest of the cast sang in French) on the 29th of August.

Apparently resting her voice for the remainder of 1922, she was at La Fenice, Venice in January 1923 for La sonnambula with her old colleague Fernando Carpi. Her next contract began back at Ravinia Park, with La traviata on the 23rd of June, Tito Schipa alternating with Giacomo Lauri Volpi. Schipa also sang with her in Lucia, Il barbiere, Lakmé, Rigoletto, Marta, L’elisir d’amore, and Roméo et Juliette. The season finished with a gala performance on the 3rd of September, after which her next performance was at the Auditorium, Chicago, on the 7th of January 1924 in La sonnambula. Here again Schipa was her perfect partner in a mere handful of performances including Marta, Il barbiere, and Lakmé, and this part of her season ended with a performance of Il barbiere by the Chicago company at the Boston Opera House on the 30th of January. She resumed operations at Ravinia Park in Lucia di Lammermoor with Lauri Volpi on the 22nd of June, and this season continued until the 31st of August. Pareto appeared in Rigoletto, Marta, Carmen, and L’elisir d’amore with Lauri Volpi, who also joined her in Fra Diavolo, which she was singing for the first time, on the 23rd of August. She sang La traviata and Il barbiere with Armand Tokatyan, who also took the role of Lorenzo in Fra Diavolo, and repeated her Lakmé with Giovanni Martinelli. After a holiday she returned to the Auditorium, Chicago on the 8th of November with Les pêcheurs de perles, followed by Il barbiere, Lakmé, and La traviata with Schipa; in Verdi’s opera she was alternating with Claudia Muzio … fortunate Chicago! It will be noticed that, except for four performances of La sonnambula in Venice in January 1923, all Pareto’s appearances between January 1922 and December 1924 were with the Chicago company.

The end was now in sight. In 1925 Pareto sang only five performances, all in February at the Barcelona Liceu: Rigoletto and Il barbiere with Carlo Galeffi. Pareto’s only traced performances in 1926 were at the Liceu, Barcelona: Rigoletto with Hipolito Lazaro and Carlo Galeffi on the 8th of February, followed by Il barbiere and La traviata. In April she sang concerts in Siena and Florence, then returned to Buenos Aires for Amleto with Ruffo, Fany Anitua, and Ezio Pinza conducted by Gino Marinuzzi on the 29th of May, Il barbiere with Ruffo and Pinza conducted by Gabriele Santini on the 27th of June, Don Pasquale with Giuseppe De Luca, conducted by Marinuzzi on the 4th of July, and Rigoletto with Lauri Volpi, Luisa Bertana, Giuseppe De Luca, and Tancredi Pasero, conducted by Marinuzzi, on the 13th of July. The company repeated Don Pasquale, Amleto, Rigoletto, and Il barbiere in Rio de Janeiro in August. Newspaper reviews wanted to be kind, but noted a falling-off in her powers and audiences were sometimes cold: many years later Lauri Volpi recalled how shocking it was when nobody applauded her after “Caro nome”. It is interesting to note that, in a concert in Buenos Aires in that same August, Pareto sang some of the Catalan songs that she had recently recorded.

In December 1926 the widowed Pareto married her second husband, Doctor Fernando Arena in Assisi, and clearly took some time off from singing, for her next traced performance, apart from occasional concerts, was La traviata in Zürich on the 30th of May 1931, followed by a spectacular winding-up of her stage career at the 1931 Salzburg Festival: Don Pasquale on the 26th of July with Tommaso Alcaide, Fernando Autori, and Mariano Stabile, Il matrimonio segreto on the 30th of July, with Laura Pasini, Giuseppina Zinetti, Cristi Solari, Enrico Vannuccini, and Umberto Di Lelio, and Il barbiere on the 31st of July with Dino Borgioli, Mariano Stabile, Vannuccini, and Autori.

Apart from some concerts in Siena (22nd of November 1931) and Florence (21st of May 1935) the delicious voice was heard no more, except on her excellent phonograph records.

THE PARETO LEGACY

– “THE QUINTESSENCE OF GRACE”

• • • • •

A total of thirty-six sides is not really enough from this delightful singer; in particular, we regret that she did not record the “Mad Scene” from Hamlet, for Ophelia may have been her greatest role. In comparison with Maria Barrientos and Mercedes Capsir, with whom Maurizio Tiberi deals in his exhaustive survey, and, indeed, in comparison with other rival sopranos from the Iberian peninsula such as Regina Pacini, Josefina Huguet, Maria Galvany, or Esperanza Clasenti, Pareto is restrained, private, ladylike; however, neither her air of aristocratic distinction nor the limited volume of her voice can interfere with the delicate shades of emotion that she can convey, as her outstanding record of Violetta’s Act One aria amply demonstrates.

“Exquisite beauty, haunting pathos and flawless purity”—Beecham’s encomia on Pareto are exactly what she has managed to impress onto wax in her phonograph records, especially in the excellent London series of 1920. In her very first discs, made in Milan in late 1907, her singing is remarkably accomplished considering that she was only eighteen years old and so far had only sung in one operatic production, as Micaëla. Would that all debutantes sounded as fresh and yet as skilled as this! Artistically her most ambitious offering is the final scene from La sonnambula, an opera that she was even then preparing for her first appearances in Madrid in December. Her thorough training is immediately apparent: the voice, of lovely quality though evidently small sized, has been so well placed by her expert teacher that every note is pearly, limpid, and unforced in a perfectly equalized scale. Her enunciation is clear and polished, her vowels are properly equalized, and her very light vibrato, less obvious perhaps on the “O” than on other vowels, is never disturbing. In her earliest records her “A” vowel is sometimes too open, but to some extent she would later correct this. With the passing of a few years of professional singing the voice would acquire more volume, but not much. Reports of the voice being small are frequent, but of her being inaudible reports are rare. Her florid singing is more accurate than that of many of her contemporaries, and her variations include some effective staccato flights. She cannot stun or dazzle us like Tetrazzini, but audiences were almost always charmed and enchanted by her refined, delicate, and tastefully expressive singing.

Her performance of “Ah! non credea mirarti” and “Ah! non giunge” may be regarded as the typical result of expert drilling by a knowledgeable teacher who had made his singing career in the nineteenth century and may be recommended to student singers today as a useful guide both to vocal technique and to style of interpretation (CD 1/2-3). Maestro Sabajno, sometimes impatient with his singers, leads Pareto lovingly through the Andante cantabile: a singer could wish for no more sympathetic accompaniment, for he is ready to hold back just when Pareto, too, wants to linger. Sopranos! Listen to how perfectly Pareto places the first note, in mixed chest and medium registration, on the E-natural, first line, on the exclamation “Ah!” (even Tetrazzini and Sutherland had a little trouble with this note). Throughout the aria her attack is flawless, her legato a perfectly drawn line. She interpolates a lot of variations; of course, Maestri Vidal and Sabajno were perfectly aware of the “traditional” interpretation of the aria as handed down from Pasta and Malibran to Patti, and Graziella might even have heard Patti’s record, for some of her ornaments are identical. Where the aria passes into the major, at “Potria novel vigore”, Pareto suddenly interpolates a splendidly effective high C on the offbeat, just as Tetrazzini would in her records; this was a Malibran ornament, as we know from Garcia’s Traîté complet de l’art du chant (though Malibran had transposed the aria a tone down), and to accomodate this interpolation Sabajno has not only to slow down and wait while Graziella holds her triumphant C, but even to cut out the orchestral accompaniment for the first half of the bar. Another delightful, old-fashioned ornament that Pareto introduces frequently here is the suono ribattuto [literally, repeated sound] that, in bel canto music, was often used to simulate sobbing without breaking the musical line: the first example comes at the end of the first section, on the sustained C of “ah sol durò”. Her interpolated trills are nicely defined in this aria. She executes the cadenza as written with great neatness, then on the very last phrase introduces a nice crescendo and diminuendo on the G above the stave. It has always surprised me that in defiance of tradition, neither Callas nor Sutherland introduced ornaments into “Ah! non credea mirarti”, but we can learn from Patti, Pareto, and Tetrazzini what nineteenth-century audiences expected. With the cabaletta “Ah! non giunge uman pensiero” we sense a few limitations to the teenage diva’s showmanship: some of the traditional variants are there to grace the aria but she is unable to contrast the haunting loveliness of her dreamy andante cantabile (sleepwalking, after all) with a truly energetic and invigorating allegro. Then, right at the very end, she stuns us with a sustained high F! She remains a remarkably talented teenager and her style is impeccable. It is a great pity that her 1918 recordings of “Come per me sereno” and the other Sonnambula arias were not issued, but at least her delightfully light and airy cabaletta “Sovra il sen la man mi posa” was included in the 1907 series (CD 1/1). Here the voice is pale and lunar in timbre (though still appealingly human) and her execution is more accurate than that of the more golden-voiced Galli-Curci. A child of her time, she makes the traditional cuts, her charming variations are also mostly traditional, but include some personal staccato effects. She offers an easily taken and well sustained high E-flat at the conclusion.

After Callas and Sutherland we are no longer accustomed to hearing “little girl” voices in Lucia di Lammermoor, but in 1907 the two Pareto records comprising the “Mad Scene”, carefully sung with sweet and pure tone, represent what audiences might have expected from a Lucia in her day (CD 1/5-6). Two rival records—wild, even frenzied, but coarsely exciting—by Maria Galvany appeared in the G&T catalogue at about the same time: Pareto is so much more musical, more accurate, more delicate that it is difficult to imagine her Lucy of Lammermoor stabbing her husband to death on their wedding night, whereas with Galvany …. Pareto’s cadenza is based on the familiar Marchesi pattern but not quite like any other version: she sings it with great precision apart from not well-defined trills. She interpolates a full-voiced high F before settling on the familiar tonic high E-flat. In “Spargi d’amaro pianto” she does not seem ever to get her trill to work properly, but the variations in the second strophe are charmingly done. In the cabaletta “Quando rapito in estasi” from Act One of Lucia she is again satisfyingly accurate in her interesting variations, based on familiar ones (CD 1/4). Although she was still studying Gilda in the classroom, her record of “Caro nome” shows that she had already mastered the aria (CD 1/7). This is also, gratifyingly, one of the best recordings in the series. There is a cut of one page to accommodate the coda, over which, interestingly, both soprano and conductor linger lovingly. Like other sopranos who could do it, Pareto finishes the coda by ascending to a high E-natural. Surprisingly, her interpretation includes a few “modern” features: she sings the opening phrases exactly as written, with all the pauses that Verdi may have meant to give a hesitant, perhaps gasping effect, and joins the phrases as indicated by the composer. She seems to trill better in Verdi than in Donizetti! In 1918 she repeated “Caro nome” for HMV, an equally attractive record though now she has transposed the aria down a semitone into E-flat, a common transposition at that period (CD 1/13). This time she includes the recitative, but omits

the coda, while the main body of the aria is sung complete.

She had ready in her repertoire the “Bell Song” from Lakmé and the vocal arrangement of Johann Strauss’s “Voices of spring”, both of which would later figure not only in her concerts but also in Rosina’s “Lesson Scene”. The Lakmé is a particularly attractive record, for like Tetrazzini and Callas she is able to contrast the wistful, dreamy and would-be “oriental” opening with a delicate but sparklingly accurate execution of the staccato passages representing “La magica squilletta dell’incantator”—the wizard’s little magic bells (CD 1/8). It is perhaps disconcerting when Pareto passes rather obviously into a completely different flute-like register to attack the high B-natural at the end of the Andante, almost as though another soprano had been engaged to sing just that one note, but she is trying to observe the classical Italian rules for registration and at her immature age the seams between the registers might well have been more evident than they would later become. Although in “Voci di primavera”, even when the record is played at the right slow speed, she sounds more like an infant prodigy than a young lady of eighteen, in compensation she offers some accomplished trills, scintillating staccati and brilliant high notes (CD 1/9). However, Sembrich and Tetrazzini eclipse her in this number with their highly professional accuracy and energetic launching into the melodies. Pareto would show that she had mastered the waltz song style when she came to record “Il bacio” in 1920.

In 1908 Pareto returned briefly to the G&T studio, leaving us a souvenir of her Micaëla with the aria “Io dico, no, non son paurosa”, a very rare record (CD 1/12). As might be expected, the music suits her to a tee. The performance must have been well rehearsed (not always the case in recording studios c. 1908) because Sabajno and Pareto allow themselves considerable flexibility of tempo, to the advantage of the music. I particularly like the way that Sabajno interprets the instruction crescendo as automatically involving an accelerando. My copy of the Italian score of Carmen belonged to the soprano Marie Rôze Mapleson and is filled with illuminating pencilled-in details of nineteenth-century musical interpretation and staging, and Madame Rôze Mapleson has marked with a corona the (to us) unfamiliar fermata that Pareto makes twice on the upper G of “Ma se vo’ far la coraggiosa”. She had already begun to sing frequently with Titta Ruffo, and nobody saw anything incongruous in partnering Ruffo’s enormous voice with the delicacy of Pareto’s limpid tones. Their record of the final duet from Rigoletto, “Lassù in cielo”, is very successful (CD 1/11). The music would have been unfamiliar to many audiences because Patti and her contemporaries had always cut out this duet; until Melba and Mario Ancona restored the Finale at Covent Garden in 1894, the curtain had usually come down on Gilda’s stabbing by Sparafucile at the end of the Trio. Both Ruffo and Pareto have observed Verdi’s markings for phrasing, and both sing and perform well, while Maestro Sabajno is in his element with Verdi’s dramatic contrasts. The duet from Don Giovanni is not so outstanding, for Ruffo tends to bellow his approaches to the artful but hesitant Zerlina, but at least they take the second part, correctly, allegro (CD 1/10).

Ten years after making her first recordings as a more than promising debutante, Graziella Pareto was called back to the Milan studios of His Master’s Voice at the height of her very successful career: unfortunately only a new “Caro nome” and four ensemble records were published, her enticing list of solo arias being consigned to oblivion. This precious handful does not start off well with the brindisi from La traviata: the regrettable tenor Lamberto Bergamini has a decent, slightly throaty voice with a goaty vibrato, and although his vocal emission seems uninhibited on the vowels “A” and “O”, the tone tends to disappear on the other vowels (CD 1/16). Worse, he cannot, even once, clearly articulate the group of four semiquavers preceded by an acciaccatura so typical of the melody (and in which Caruso and Alma Gluck are much more precise). Alas, when Pareto enters, her articulation of this repeated musical figure is equally sketchy! He is better, but still unlovely, in the duet “È il sol dell’anima” from Rigoletto in which Pareto maintains her purity of tone and careful attention to the legato line (CD 1/14). In “Sì, vendetta” from Rigoletto we hear the well-trained baritone Matteo Dragoni giving the “traditional” phrasing, and welcome this is (CD 1/15). Reviews often mention that despite her small voice Pareto was very good in this scene, and it must be said that without any shouting or other exaggeration she sings all the notes and keeps up with Sabajno’s incandescent pacing of the duet. And yes, at the end the Maestro obligingly stops the orchestra and waits while Graziella emits a piercing high E-flat, Dragoni politely listening to her, then he blazes away at his high A-flat only when she comes down from the stratosphere. The record is effective, but we could wish that Pareto had been placed a little nearer the recording horn.

The much superior recording technique in the records made by HMV in London in 1920 finally gives us a fuller impression of the lovely quality of Pareto’s voice, and her artistry is more clearly paraded before us. There is even an orchestra that sounds more like an orchestra, and the conducting is in the safe hands of Percy Pitt; what a pity that there are only seven sides, for each one is a gem. Perhaps the most winning of all is her first husband’s song “O bimba bimbetta” (O tiny little child), composed in 1915 and dedicated to—Florica Christoforeanu (CD 1/19)! A fairly simple song containing a few easy florid gruppetti, “O bimba bimbetta” brings out all Pareto’s appealing vocal enchantment. Hers is one of the most original and pleasing records of Arditi’s immortal “Il bacio” (Rossini begged Arditi to give the world more “kisses”) and perhaps only her compatriot Josefina Huguet, less inclined to ladylike reticence, beats her to the winning post with her impulsive and galvanizing romp through the piece (CD 1/18). Graziella has persuaded Percy Pitt to indulge her in endless rallentandos with a view to enrapturing her audience with winning pianissimo effects, which is delightful, but Arditi’s tuneful warhorse was not meant to be held up constantly while the soprano showed off her softly suspended notes. Adelina Patti, breathless though she be in her wonderful unpublished record, keeps the rhythm going with a minimum of holds [Marston 52011-2, Adelina Patti & Victor Maurel]. The aria “Siccome un dì” from I pescatori di perle is a lovely record, sung with infinite care for the sinuous vocal line (CD 2/5), and even better is Norina’s aria from Don Pasquale (CD 2/2). The opening section, “Quel guardo il cavaliere” is ravishingly sung, without any hint of caricature (which, however, Donizetti may well have wanted more of here), but Pareto successfully effects the necessary transition to winsome coquetry—without the traditional interpolated laughter, which I rather miss—adopting a charmingly light and piquant tone for “So anch’io la virtù magica”. In this brilliant performance, furnished with a solid high C, spectacularly fluid runs and a fine trill (that gradually unravels into a sustained single note—was this intended, Graziella?), we get a rare glimpse of a Pareto for once portraying neither a dishevelled lunatic maiden nor a wistful wayside flower. The rather sudden ending might well be an established theatrical cut. In Susanna’s aria from Le nozze di Figaro, Pareto and Percy Pitt thankfully give us the traditional “Vienna” tempo, heard also in the recordings by Sembrich and Lotte Lehmann, and Pareto’s singing is most beautiful (CD 2/1). Strange to tell, although she sings most of the appoggiaturas in the recitative, she leaves them out in the aria! Like most sopranos, she is principally concerned with bringing out the celestial beauty of the music with all her mastery of limpid tone and legato line, and, like others (not Lotte Lehmann, however) she tends to overlook the strongly erotic element in the music and dramatic situation. Perhaps her most detailed and carefully thought-out interpretation is her triumphant record of Violetta’s “Ah, fors’è lui”, one of the very best performances on 78-rpm records (CD 2/3). She is in flawless voice. Her musical interpretation is a curious mixture of “ancient and modern”: she sings the recitative “È strano” clearly and expressively, without paying undue attention to note-values as marked in the score, which is exactly how Garcia instructs us to sing recitative—laying the stress on the syllables where it would fall in speech. On the other hand, unlike Tetrazzini and some other sopranos wedded to traditional variants, she follows the score literally by not waiting for the orchestra to finish before she sings “Che risolvi, o turbata anima mia?”. In the opening phrases of the aria she phrases “ah / for / s’è / lui” exactly as written, with all the marked pauses, while introducing old-fashioned upward portamenti to join the phrases. She concludes the cadenza with a fine crescendo and diminuendo on the high C. In the recitative “Follie! Follie!” her attack on “Gioir!” is a little too heavy, but she takes the high D-flat securely in her stride (CD 2/4). “Sempre libera” is neatly executed, though trills on lower medium notes are not her strong suit, and she manages the ascents to high C impressively. She concludes by interpolating the now expected high E-flat, though this showy variant cannot be called “traditional” because Patti and her contemporaries eschewed it: Tetrazzini was probably among the first to introduce this note here.

In 1924 Pareto seems still to have been in excellent voice for her only two published recordings made for HMV in Milan. Giovanni Manuritta assists her in the sublime ensemble from La sonnambula, in which Pareto, distantly placed, joins in singing the tenor’s line as was, and is, usually done (CD 2/7). Manuritta sings Elvino’s music rather well, but the chorus tends to drown out the soloists. Both Pareto and Fernandino Ciniselli sing the Pescatori di perle duet elegantly, with considerable feeling (CD 2/6).

In Barcelona in 1926 Pareto, virtually at the end of her career though only thirty-seven years old, made five double-sided late acoustic records of Catalan and Spanish songs, all very rare indeed. These are beautifully recorded and, like the London records, allow us to hear the full beauty of this bewitching voice. There is no sign of any vocal deterioration, unless we count the careful avoidance of any note higher than A. The middle register, the one most subject to wear in a twenty-year career, is full, fresh, and limpid—certainly fuller and probably even more beautiful than when she was eighteen years old. The records were obviously planned for Catalan buyers, but today they will delight all those who have fallen in love with her operatic records. “Dolor de amor” is the most dramatic number, while “La piel de mi amado” brings out the delightfully piquant side of her personality (CD 2/10 and 18).

ELVIRA DE HIDALGO [so]

(Valderrobres, Spain, 1891 – Milan, 1980)

Remembered today as the teacher and inspiration of Maria Callas, Elvira de Hidalgo was a highly-regarded coloratura soprano with an international career. She was born in Valderrobres, Spain and received her principal vocal training from Melchiorre Vidal, who had also taught Graziella Pareto, Maria Barrientos, Rosina Storchio, Fernando Valero, and Francesco Viñas. At the age of sixteen, she made her debut at the San Carlo in Naples as Rosina in Il barbiere di Siviglia, a role she would sing throughout the operatic world. She soon was singing in Paris, Monte Carlo, and Prague, and in 1910 she made her Metropolitan debut in her favorite role of Rosina. There she also sang Gilda in Rigoletto and Amina in La sonnambula. She again sang Rosina for her 1916 debut at La Scala, and appeared the following year at the Teatro Colón in her usual roles of Rosina and Gilda, with the addition of Violetta in Traviata. In 1924 she appeared at Covent Garden as Gilda, and sang in Lakmé and Barbiere at the Chicago Opera. She returned to the Metropolitan in the 1924–1925 season, and in 1926 toured the U.S. singing in Barbiere with the great Feodor Chaliapin. Moving to Athens in the 1930s, De Hidalgo taught at the Athens Conservatory. In the fall of 1939, the sixteen-year old Maria Callas enrolled there and De Hidalgo became her teacher, nurturing and encouraging her prodigious talent. De Hidalgo died in Milan at the age of eighty-eight, outliving her illustrious pupil by over two years. Her earliest recordings were made for Columbia around 1908, followed by a group of Fonotipias in 1909. She recorded nine sides for English Columbia in 1924, and finally a group of fourteen songs recorded by HMV in Athens, 1933 and 1934, of which only eight were released.