CD 1 (61:25) | ||

Rachmaninoff Demonstrates His Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 | ||

| Impromptu performance at the piano | ||

| 1. | I. Non allegro (bar 1 to bar 41) | 1:34 |

| 2. | I. Non allegro (bar 48 to bar 236) | 8:02 |

| 3. | I. Non allegro (pickup to bar 241 to 263) | 1:04 |

| 4. | II. Andante con moto, Tempo di valse (beginning to bar 176) | 7:00 |

| 5. | II. Andante con moto, Tempo di valse (middle of bar 182 to end) | 2:14 |

| 6. | III. Lento assai — Allegro vivace — Lento assai, Come prima — Allegro vivace (bar 8 to bar 214) | 7:10 |

| An edited version of the original recording, with most of the repeated phrases and spoken comments removed, and with the music presented in its proper score sequence | ||

| 21 December 1940 | ||

Rachmaninoff: Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 | ||

| 7. | I. Non allegro | 11:57 |

| 8. | II. Andante con moto, Tempo di valse | 9:45 |

| 9. | III. Lento assai — Allegro vivace — Lento assai, Come prima — Allegro vivace | 12:38 |

| with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos | ||

| 20 December 1942, New York City | ||

CD 2 (76:31) | ||

Rachmaninoff: The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 | ||

| 1. | Introductory radio announcement followed by Eugene Ormandy speaking about Rachmaninoff | 2:54 |

| 2. | The Isle of the Dead, Op. 29 | 18:42 |

| with the Philadelphia Orchestra conducted by Eugene Ormandy | ||

| 2 April 1943, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (This performance was given as a memorial to the composer five days after his death on 28 March) | ||

Rachmaninoff: Symphony No. 3 in A Minor, Op. 44 | ||

| 3. | I. Lento — Allegro moderato — Allegro | 15:14 |

| 4. | II. Adagio ma non troppo — Allegro vivace | 11:32 |

| 5. | III. Allegro — Allegro vivace — Allegro, Tempo primo — Allegretto — Allegro vivace | 12:07 |

| with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra conducted by Dimitri Mitropoulos | ||

| 21 December 1941, New York City | ||

| 6. | Belilitsï rumyanitsï, vy moi (Powder and Paint) (Russian folk song, arranged by Rachmaninoff) | 3:50 |

| Nadezhda Plevitskaya, mezzo soprano, with Sergei Rachmaninoff, piano Victor Talking Machine Company private recording, made for the composer | ||

| 22 February 1926, New York City | ||

| (Note: This song was used as the third of Rachmaninoff’s “Three Russian Songs for Chorus and Orchestra, Op. 41.” The Victor recording logs give the title as “Powder and Paint”) | ||

Rachmaninoff: Three Russian Songs for Chorus and Orchestra, Op. 41 | ||

| 7. | I. Cherez rechku (Over the Stream), Moderato | 3:30 |

| 8. | II. Akh ty, Vanka (Oh, My Little Johnny), Largo | 4:40 |

| 9. | III. Belilitsï rumyanitsï, vy moi (You, My Fairness, My Rosy Cheeks or “Powder and Paint”), Allegro | 4:04 |

| with the American Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leopold Stokowski, with the Schola Cantorum | ||

| 18 December 1966, New York City | ||

CD 3 (66:37) | ||

Rachmaninoff: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43 | ||

| 1. | Introductory radio announcement | 1:45 |

| 2. | Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 43 | 23:12 |

| Benno Moiseiwitsch, piano, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Adrian Boult | ||

| 14 September 1946, London | ||

| 3. | Russian folk song: Bublichki (Bagels) | 1:26 |

| with Rachmaninoff accompanying friends at a party, circa 1942 | ||

| 4. | Rachmaninoff: Polka Italienne | 0:36 |

| with Sergei and Natalia Rachmaninoff, piano | ||

| private recording, circa 1942 | ||

| 5. | Rachmaninoff plays ballades: Brahms Op. 10, No. 2, in D (middle of bar 145 to bar 150), and Liszt No. 2, in B Minor (through the end of bar 125; bars 77-79 omitted) | 6:24 |

| recorded by Bell Telephone Laboratories during a Rachmaninoff recital at the Academy of Music | ||

| 5 December 1931, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | ||

Rachmaninoff Demonstrates His Symphonic Dances, Op. 45 | ||

| Impromptu performance at the piano | ||

| 6. | Side 1: Movement I. Non allegro (bar 48 to bar 236) | 9:32 |

| 7. | Side 2: | 9:19 |

| Excerpt 1: Movement I. Non allegro (pickup to bar 241 to bar 263) | ||

| Excerpt 2: Movement III. Lento assai — Allegro vivace — Lento assai, Come prima — Allegro vivace (bar 8 to bar 214) | ||

| 8. | Side 3: Movement II. Andante con moto, Tempo di valse (beginning to bar 176) | 9:17 |

| 9. | Side 4: | 5:05 |

| Excerpt 1: Movement II. Andante con moto, Tempo di valse (middle of bar 182 to end) | ||

| Excerpt 2: Movement I. Non allegro (beginning to bar 41) | ||

| The unedited, complete recording, with each of the four acetate sides presented as track points | ||

| 21 December 1940 | ||

• • • • •

The recording of Sergei Rachmaninoff playing his Symphonic Dances is reproduced from the original discs in the Eugene Ormandy Collection of Test Pressings and Private Recordings, 1930-1983, Ms. Coll. 440, with the permission of the University of Pennsylvania.

Producers: Gregor Benko, Francis Crociata, Scott Kessler, and Ward Marston

Audio Conservation: Ward Marston, J. Richard Harris, and Raymond Edwards

Photographs: Anonymous, Gregor Benko, Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library, Lion Heart Autographs, and the Rachmaninoff Network

Booklet Design: Takeshi Takahashi

Marston would like to extend a special thank you to Jay Reise, whose discovery of the Symphonic Dances was the genesis of the project and whose continued help and patience shepherded the project to fruition; to Gregor Benko and Francis Crociata, whose concern, knowledge, and tireless efforts helped make this project possible; and to Richard Taruskin and Ira Levin, whose essays provide context and insight.

Marston wishes to thank Mark Arnest, Maxwell Brown, Frank Cooper, Joseph S. Crociata, Jr., Johan Falleyn, Margarita Glebov, Andrew Hauze, International Piano Archives at Maryland, Jeffrey Javier, Natalie Wanamaker Javier, Neal Kurz, Library of Congress Rachmaninoff Archive, David Lowenherz, Donald Manildi, Kevin Mostyn, Elger Niels, Mark Obert-Thorn, Gene Pollioni, Larisa Soboleva, Jonathan Summers, Simon Trezise, Wouter de Voogd, and Irina Yakovenko

Our thanks to Claire Hoeffler for the Stokowski recording from the collection of Paul Hoeffler

Marston is grateful to Peter Greenleaf for his financial contribution to this CD set.

Marston is grateful to the Estate of John Stratton (Stephen R. Clarke, Executor) for its continuing support.

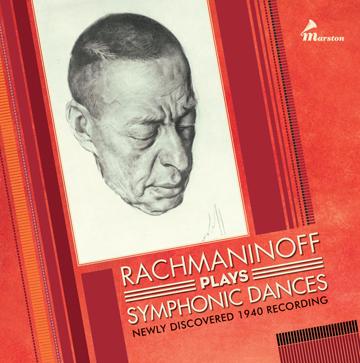

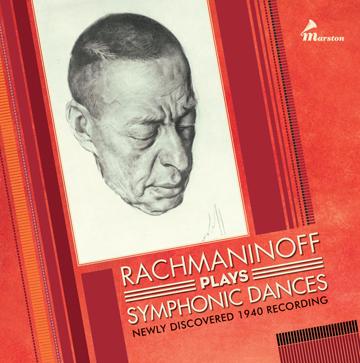

RACHMANINOFF PLAYS SYMPHONIC DANCES

—Newly Discovered 1940 Recording—

So I start on A-sharp?” Sergei Rachmaninoff asked his passenger. “Right,” said Robert Russell Bennett, and they drove on. Rachmaninoff had invited Bennett over to Orchard Point, the Huntington, Long Island estate where he was staying in the summer of 1940, to hear the orchestral composition he had in progress. At this point he was thinking of it as “Midday, Twilight, Midnight,” and (after at first imagining Marian Anderson’s voice as its ideal medium) he wanted to give the long melody he had written for the middle section of the Midday movement to the saxophone, probably because of the plaintive effect Ravel got from it when orchestrating the troubadour melody in “The Old Castle,” one of Musorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, at Serge Koussevitzky’s request. Rachmaninoff, who had never written for the instrument, didn’t know which saxophone to use, or how the various sizes were pitched. Bennett, a friend and trusted assistant to the recently deceased George Gershwin, was then the top Broadway and Hollywood arranger. He knew saxophones.

The range of Rachmaninoff’s melody suited the alto sax, pitched on E-flat, so that the melody, in C-sharp minor, needed to be transposed in the score to the improbable key of A-sharp minor, with seven sharps. Bennett, having reassured him that the transposition was correct, then had the rare pleasure of hearing Rachmaninoff play through the new and as yet not fully orchestrated triptych at the piano, “and I was delighted,” he later told Rachmaninoff’s biographers, to see his approach to the piano was quite the same as that of all of us when we try to imitate the sound of an orchestra at the keyboard. He sang, whistled, stomped, rolled his chords, and otherwise conducted himself not as one would expect of so great and impeccable a piano virtuoso.1

Now we can all share Bennett’s delight in Rachmaninoff’s singing and stomping, thanks to the chance preservation and fortunate discovery of the private (perhaps surreptitious) recording at last made public here, of another impromptu solo rendition by the composer of the same work—Rachmaninoff’s last, which the world now knows as his Symphonic Dances, Op. 45—on 21 December, 1940, less than two weeks before its dedicatees, “Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra” (as printed in the published score), gave the world première on 3 January 1941. Never nearly as prolific in exile as he had been in Russia, Rachmaninoff found neither the time nor the mood to compose after finishing the Dances, which in a gloomy moment he called his “last flicker.”2 The only creative tasks he accomplished in his last two years were a posthumously published revision of his Fourth Piano Concerto (for which his widow called again on Robert Russell Bennett to complete the piano reduction of the orchestral score) and one last encore piece for use in his recitals: the florid arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s “Cradle Song,” Op. 16, No. 1, which he completed later in 1941 and recorded the next year in one of his last RCA Victor sessions.

The makeshift recording of the Symphonic Dances, on two double-sided 10-inch acetate discs of the sort then used for home recordings, was probably made at Ormandy’s house. There are several reasons to suspect that it was done covertly. The microphone was placed very far from the action—frustratingly so, for although the piano comes through clearly enough to make listening enjoyable as well as instructive, the occasional verbal interjections have resisted all efforts to transcribe them. (There have been various conjectures, none consequential; listeners to the CDs are welcome to try their luck.) The four sides neither begin at beginnings nor end at endings, suggesting that Rachmaninoff was unaware of when the recording device was switched on and when the discs were turned or changed. For this reason, the recorded music is presented here twice: first in an ordering that more or less follows the score (breaking off in the middle of the third movement), and then as recorded live.

The main reason for assuming that the records were made literally behind the pianist’s back is that Rachmaninoff never permitted his live performances to be recorded or broadcast. All of his extant recordings except this one were inscribed under tightly controlled studio conditions. The only exceptions are eavesdroppings like the one on the Symphonic Dances, which is by far the most substantial of them. The others, also included here, are dimly recorded fragments of ballades by Liszt and Brahms from a Saturday matinee recital in Philadelphia (5 December 1931), picked up by engineers preparing to record another concert later in the day; and, finally (and truly insignificant), a couple of souvenirs of a gathering at Rachmaninoff’s West End Avenue apartment in New York (possibly a surprise party for his last birthday, in April 1942): a bawling rendition by the company of an urban folksong (sometimes sung in Russian, sometimes in Yiddish) called Bublichki (or bagels), with the host accompanying on a barely audible piano, and an impromptu four-hands rendition, with his wife, of Rachmaninoff’s early “Italian Polka.”

These are trifles, but the run-through of the Symphonic Dances is a major document, for the Dances were a major work. In the short time left to him, Rachmaninoff always called them his best composition. Few agreed at the time. Charles O’Connell, the artists-and-repertoire man at RCA Victor, thought so little of them that he passed up the opportunity of recording them under the composer’s baton (and told the story, quite unflatteringly, in his memoirs).3 By now, though, the Dances have overtaken in frequency of performance all the other orchestral works of Rachmaninoff’s without solo piano. In his hands they are indeed a major statement. Besides the extraneous sounds that delighted Robert Russell Bennett (including the shouted “Badabada BAA” to simulate the timpani tattoos near the beginning of the first movement), one hears a relaxed yet enthusiastic Rachmaninoff alternately tearing through his dances and caressing them, giving an astounding if casual demonstration not only of his affection for them but also of his skill at reducing a complex orchestral score to what can be encompassed by two huge yet preternaturally supple hands.

No conductor should miss Rachmaninoff’s demonstration of what he meant by marking the first movement of the Symphonic Dances “Non allegro.” Many have been misled into thinking that it means “not fast.” One of them, at first, was Dimitri Mitropoulos, whose December 1942 performance with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra is included in this set. He had done the work a month earlier in Minneapolis, at a concert for which Rachmaninoff had been engaged to play his most popular piano concerto, the Second. William McNally, the critic for the Minneapolis Star Tribune, attended the first rehearsal, and watched as the composer, pacing and frowning in the wings, began loudly snapping his fingers to get Mitropoulos to speed up. The conductor stopped the orchestra, whereupon Rachmaninoff reached into the score on the podium and crossed out the “Non” before “allegro.” (The critic mistakenly thought he was correcting a misprint.)4 Mitropoulos learned fast, and produced a performance that Rachmaninoff thought definitive. “It will never be played better,” he told the conductor, and asked him expressly to repeat the Dances in New York (replacing the scheduled Poem of Ecstasy by Scriabin) so that he could record the Sunday broadcast at home. (That is the performance included here, taken not from Rachmaninoff’s home recording but from professionally recorded airchecks.)

What Mitropoulos learned is that, rather than “not fast,” Non allegro meant “not as fast as it may look at first glance.” The music is notated in “common time,” four quarter-note beats per measure, but there is a pervasive pulsation of eighth notes (marked molto marcato) accompanying the main theme, all of which need to be executed with an “ictus”—that is, the sort of metrical stress normally given to the beating value, in order to produce the quick yet heavy, throbbing tread that Rachmaninoff captures so perfectly in his piano demonstration.

Anyone following Mitropoulos’s performance with the published score is in for a surprise at rehearsal figure [7] in the first movement (2:08 on CD 1 Track 7), where the piano, which in the first two movements has a small part to play in the percussion section of the orchestra, gets a little virtuoso moment, twice accompanying the melody with a rapid chromatic scale in thirds. These were evidently added in rehearsal—possibly for Ormandy originally, whose première performance was not recorded (though Rachmaninoff, in the run-through at Ormandy’s only days earlier, does not play them). They can be heard in recorded performances by conductors who worked with Rachmaninoff or from rental parts that went back to composer-supervised performances—besides Ormandy’s studio recordings and Mitropoulos’s with the Philharmonic, they include those of Artur Rodzinski, Erich Leinsdorf, Leopold Stokowski, and Eugene Goossens. They were published as one of three “Composer’s Amendments” in the prefatory material to the 2005 Boosey & Hawkes edition of the full score, but even recent performances rarely include them. Perhaps now that they have been documented in this Mitropoulos recording for which the composer was present, they can become “canonical,” as the composer surely intended.

Another aspect of Rachmaninoff’s private recording that public performers might try to emulate is his variable tempo—far more flexible than even he usually produced when recording his work for posterity. The score is full of marked accelerandos and rallentandos, but these are only the grossest gestures on a sprawling scale of perpetual tempo rubato. Now that we can overhear his private playing, the contrast with his rather severe and phlegmatic public persona is often striking. Before audiences his reserve, epitomized by his crewcut in an age of manes, was legendary—“a tower of apathy,” one critic called him in an obituary.5 Comparing his demeanor to that of the mercurial Scriabin, Boris Pasternak’s younger brother Alexander recalled Rachmaninoff sitting “at the piano with the same seriousness and simplicity as he must have sat down at his writing desk or at meals in front of a plate of soup.”6

Despite his undemonstrative exterior, he could take rubato to extremes, even in public, that often outstripped the emotings of more overtly flamboyant types—Mitropoulos, for example, whose bodily involvement with the music he was leading (like Leonard Bernstein’s later on) could strike onlookers as verging on indecency. (Gunther Schuller, who watched Mitropoulos from the horn section of the New York Philharmonic as he conducted Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony, was “convinced that he was having an emotional orgasm.”)7 Rachmaninoff liked Mitropoulos’s performances of his Third Symphony as much as he did the Symphonic Dances (which is why Mitropoulos’s 1942 broadcast is included here) but Mitropoulos came nowhere near the audacity of Rachmaninoff’s own shaping, in his 1939 studio recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra, of the cellos’ dolce cantabile theme in the first movement, where upbeats are stretched to something approaching double their notated length to give them the desired quality of yearning.

Rachmaninoff’s keyboard rendition of the “saxophone theme” in the first movement of the Symphonic Dances is another superb lesson in performance practice. The passage is remarkable for the sparseness of its scoring. The saxophone is mostly accompanied by wispy woodwind counterpoints in sixteenth notes that, as Rachmaninoff plays them, never settle down into a predictable groove. To get this effect in an orchestral performance would require an abnormal level of initiative on the part of the individual wind players, and of trust on the part of the conductor, but it would be worth the try. The unpredictable, meandering effect mimics the drift of lingering memory—in a word, nostalgia—which is surely the exiled Rachmaninoff’s most persistent mood.

And just as surely, no other work of Rachmaninoff’s is as drenched in nostalgia as the Symphonic Dances. It is tempting to imagine that the composer sensed that it was what it in fact turned out to be: his swan song. But that could be said with equal justice of all the orchestral works of Rachmaninoff’s expatriate years, of which four out of five are included in this set. They are all preoccupied with the symbolism of memento mori and recherche du temps perdu, nowhere more obviously than in the Dances, which bear multiple traces of their suppressed program, in which the times of day were a transparent stand-in for the life cycle. Those obdurate eighth notes that inhabit the first movement from its opening bar bring ticking clocks to mind, and the last movement adds three campane (orchestral chimes) to the list of instruments, so that they can toll twelve times (Rachmaninoff, whispering to Marcia Davenport at a Cleveland performance in 1942: “That’s midnight!”) to herald the approach of the Dies Irae, the ancient requiem chant, which has haunted the music of practically every composer since Berlioz (one published list enumerates more than fifty compositions by no fewer than thirty-four composers), and none more obsessively than Rachmaninoff’s. Three other pieces in this set of recordings (Third Symphony, Paganini Rhapsody, Isle of the Dead) all allude to this, classical music’s preeminent spook.

In the Symphonic Dances, Dies Irae is balanced against a life-asserting counterpart: the Resurrection doxology or song of praise (Blagosloven yesi, Gospodi, “Blessed be the Lord”) from the liturgy of the Vsenoshchnoye bdeniye (All-Night Vigil), the Orthodox vesper service, of which Rachmaninoff had made a masterly, now famous setting in 1915. The old Slavonic (znammenïy) chant melody on which the early choral setting was based is paraphrased in its entirety, beginning at the third bar after figure [96] in the score (11:15 on CD 1 Track 2), and when the final acclamations are reached, Rachmaninoff actually wrote the word “Alliluya” in his score, spelled the Orthodox way, reflecting its liturgical pronunciation in five syllables, the –y– counting as one of them.

But the most touching programmatic allusion in the Symphonic Dances is one that absolutely no one not named Rachmaninoff could have recognized at the time of its early performances. The softly shining coda of the first movement, Midday (=Youth), quotes, beneath a canopy of sparkling arpeggios in piano, harp, and glockenspiel, the motto theme of Rachmaninoff’s First Symphony, op. 13 (1895), whose disastrous 1897 première was so traumatic as to usher in a three-year creative block that almost scotched the composer’s budding career. The symphony had never been performed since then, and the score, left behind when Rachmaninoff emigrated in 1917, had been lost. It was not until the year after Rachmaninoff’s death that the orchestral parts were discovered (like those of Stravinsky’s long lost Funerary Chant, which turned up seventy years later) in the library of the St. Petersburg (then Leningrad) Conservatory, and so the resurrected Symphony could have a second, much more successful, première in 1945, something the composer never foresaw and never heard. The beautiful citation in Symphonic Dances—clearly the movement’s tochka, or culminating point, as Rachmaninoff used to say—changes the character of the theme from menacing (as in the original symphony) to comforting, befitting the alteration of the now elderly composer’s perspective on the great disaster of his youth. But that only made the reference doubly arcane, and may be the reason why the composer decided to discard the programmatic title in favor of a neutrally descriptive one (with “Fantastic Dances”—the title by which he referred to it when first offering it to Ormandy—coming in between).

Ormandy was the inevitable recipient of both the performing rights and the dedication, because he was probably, if indirectly, responsible for the very existence of the Symphonic Dances. During the 1939–1940 season the Philadelphia Orchestra, both at home and in New York, presented a three-concert “Rachmaninoff Cycle” in commemoration of the thirtieth anniversary of Rachmaninoff’s American debut. These concerts worked the composer very hard indeed. In the first of them he played his First Concerto and the Paganini Rhapsody after Ormandy had conducted the Second Symphony; in the second program, Ormandy conducted The Isle of the Dead and the 66-year-old Rachmaninoff had to play both of his middle concertos, a colossal assignment that would have taxed a pianist half his age. At the last concert Rachmaninoff was on the podium to conduct the Third Symphony and his largest work of all, The Bells, an oratorio (or, as the title page declares, a “choral symphony”) setting the eponymous poem by Edgar Allan Poe as freely translated into Russian by Konstantin Balmont. These concerts left him exhausted, but also morally keyed up at their warm reception, and they aroused his fragile muse. During the summer months of 1940, in the quiet and cozy atmosphere of Orchard Point, he unexpectedly bestirred himself and wrote the Dances, thinking at first to give them to Mikhaíl Fokine, who had choreographed the Paganini Rhapsody, for possible use as a ballet. (Fokine’s death in 1942, a year before Rachmaninoff’s own, put an end to this notion.)

By late August he had the piece down in particell or “short score,” and immediately invited Ormandy to Orchard Point to hear it, so that the December run-through was Ormandy’s second time through it with Rachmaninoff. Despite all this collaboration, and despite the dedication, Ormandy never liked the piece; and despite his gratitude after the Rachmaninoff Cycle, Rachmaninoff never liked the way Ormandy performed it. A few years after the composer’s death, Ormandy wrote to Olin Downes, the New York Times critic, who was advising the Philadelphia Orchestra in planning a benefit concert for the Rachmaninoff Fund, an organization that sponsored piano competitions. “I was thinking of perhaps playing the Symphonic Dances,” the conductor confided, “which is dedicated to our orchestra and myself, but in all honesty I doubt whether this is his best work although he told me he felt it was. However, we know so well that composers are not always the best judges of the merits of their works.” For his part, after a 1942 concert in Ann Arbor at which he played a concerto and Ormandy conducted The Isle of the Dead and the Symphonic Dances, Rachmaninoff wrote to his cousin-cum-sister-in-law Sophia Satina that “Ormandy played the Isle of the Dead badly, and the Dances acceptably only in spots.”8 (That is why the Dances are represented here in a performance known to have satisfied the composer throughout.) Nevertheless, Ormandy’s rendition of The Isle of the Dead, broadcast within days of the composer’s death and preceded by a touching memorial speech, does make a fitting contribution to the present offering, and has the additional merit of documenting the cuts that Rachmaninoff entered in the Philadelphia Orchestra’s score in his own hand, and also observed in his 1929 recording of the piece.

Until recently Ormandy’s has been the prevailing opinion not only of the Symphonic Dances, but of all of Rachmaninoff’s post-emigration compositions. They always received a bad press at the time of their premières, when modernist values prevailed among critics and music like Rachmaninoff’s could be written off as “contemporary music which shows no contemporary influence,” and which “could with very minor changes be a product of 1890, 1940 or—for that matter—1970,” according to Edward Barry, reviewing the Chicago première under Frederick Stock, a few days after Ormandy had unveiled the Dances in Philadelphia. After the Philadelphia première, a New York reviewer disparaged the allusions, now among the score’s chief fascinations. Because the finale quoted Dies Irae, it was “a rattling poor imitation of Saint-Saëns Danse Macabre.” The middle movement, a dark-hued waltz, was “a real rendez-vous of ghosts. … A lugubrious ennui shuffles through it, and Ravel, Richard Strauss, and Sibelius join the dance in deep purple.”9 Downright cruel was the prognosis of the critic from the Chicago Daily News who, after an evening that included the Third Symphony under Frederick Stock, the Fourth Concerto as performed by the composer, and more, compared the Russian master to Robert Rutherford McCormick, the much-reviled publisher of the rival Chicago Tribune:

Somebody described a noted Chicagoan as “a man with one of the finest minds of the 14th century.” Rachmaninoff owns one of the intriguing composing talents of the 19th century. But, to listen to an all-Rachmaninoff program is like sitting down to a seven-course dinner with Beluga caviar for each course. He no more deserves a concentrated evening than Reger, Franck or Saint-Saëns [again!] and, in 20 years, he won’t get one.10

But all pales before the non-review that Virgil Thomson, the composer-critic who in the 1940s was the New York musical tastemaker supreme, gave one of the performances included in the present set of recordings. “The Rachmaninoff Third Symphony was billed for last,” he informed readers of the New York Herald-Tribune; but “Being a trifle allergic both to Mr. Mitropoulos’s conducting and to Mr. Rachmaninoff’s writing (I don’t react the way one is supposed to), I thought it wiser to leave the concert at the intermission.”11

Now that 1970 is nearly as far in the past as 1890 was in 1940, and when it is Virgil Thomson who will never get a concentrated evening, it doesn’t hurt to quote any of this. But when one recalls that it was a cruel review of the First Symphony by composer-critic César Cui that knocked Rachmaninoff for such a loop so early in his career, one can understand why his composing had dwindled to a trickle by the end of it. In fact, besides the Fourth Concerto, the Variations on a Theme of Corelli for piano, and a slew of arrangements for use as concert encores, there is only one Rachmaninoff score completed in emigration that has not yet been mentioned in these notes, namely the Three Russian Songs for chorus and orchestra, Op. 41, composed in 1926 and dedicated to Leopold Stokowski, who gave them their first performance the next year in Philadelphia. They are among Rachmaninoff’s most unusual compositions—unrecorded until the mid-1950s—and are still very rarely performed, which is why they are represented here in a performance conducted by the dedicatee, but recorded almost forty years later, and by a chorus singing in English at a time when the earlier generation of Russian émigré musicians had died off and the newer waves of emigration had not yet begun.

The most unusual thing about them is that for practically the only time in his life, Rachmaninoff did what is often thought of as the most usual thing for a Russian composer to do, namely base an entire composition on traditional Russian music, whether folk or ecclesiastical. He often explicitly exempted himself from that stereotype, as when an organist and music scholar named Joseph Yasser proposed that the opening theme in his Third Piano Concerto was based on an Orthodox chant. Yasser asked for confirmation of his assumption, and Rachmaninoff replied, “You are right to say that Russian folk song and Orthodox church chants have had an influence on the work of Russian composers. I would only add, ‘on some Russian composers’!”12 In other words, not me.

The one exceptional work was yet another expression of Rachmaninoff’s perennial nostalgia—perhaps the most poignant one of all. The impressionistic orchestral haze that surrounds the tunes, which are sung for the most part in unison by lower voices only, whether male or female (basses in the first song, altos in the second, both together in the third)—and, most especially, the motto that sounds at the beginning of each song, so reminiscent of the magical chords that punctuate Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream or Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sheherazade—conspire to evoke not the Russia that then was—a place then “groaning under the terrible yoke of a numerically negligible but well-organized gang of Communists, who are forcibly, by means of Red Terror, imposing their misrule upon the Russian people,” as Rachmaninoff and two other prominent émigrés put it in a letter to the New York Times13—but rather the vanished and now idealized Russia he had left behind forever.

The Russian Songs also pay tribute to a pair of fellow emigrants from whom Rachmaninoff had learned the tunes: the great basso Fyodor Chaliapin, with whom Rachmaninoff had often collaborated in his long since abandoned career as a conductor of operas, from whom he learned the second song, Akh ty, Van’ka! (Oh my, little Johnny), which Chaliapin loved to sing unaccompanied as an encore (and which he recorded that way, albeit singing Ekh instead of Akh); and Nadezhda Plevitskaya, perhaps the most popular of all variety singers in the late Tsarist days, from whom he learned the third song, Belilitsï, rumyanitsï. (The first song, Cherez rechku, or “Over the Stream,” about a drake and how he lost his mate, Rachmaninoff found in a book, according to his sister-in-law.)14

That third song deserves a bit of commentary. Plevitskaya is to this day a figure of mystery. Her recent biography, Stalin’s Singing Spy by Pamela A. Jordan (2016), characterizes her in the role of a Soviet agent married to a former White Army general, now working for the Soviet secret police, implicated in the 1937 abduction from his Paris exile of another White general, Yevgeny-Ludwig Karlovich Miller for trial and execution. For this crime she was sentenced by a French court to a term of twenty years, only two of which she had served at the time of her death (from an alleged heart ailment) in 1940, shortly after the Germans had occupied France.

That, of course, is not how the staunchly anti-Soviet Rachmaninoff knew her. He remembered her as the headlining “Gypsy singer” at the famous Moscow restaurant Yar’, and as a personal favorite of Tsar Nikolai II. In 1924 he financed the publication of her memoir of her early life, Dezhkin karagod, or Dezhka’s Circle Dance (Dezhka being her childhood nickname, derived from Nadezhda, Russian for Hope). He met up with her again in January, 1926, when she came to New York on her one American tour, and brought down the house with her the next month at a benefit concert held for indigent Russian émigrés at the Plaza Hotel, having improvised an accompaniment to Belilitsï, rumyanitsï that provided the impetus from which the Three Russian Songs took shape. A few days later, the two of them booked a recording studio owned by the Victor Talking Machine Company to make a souvenir of their performance. It was first issued for public release by the Rachmaninoff Society almost a decade after Rachmaninoff’s death, and it, too, is included here.

Comparison with Stokowski’s performance of the orchestrated version amply corroborates a story told by Igor Buketoff, the conductor of the first stereo recording of the Songs, who attended the première, as well as the rehearsals for it, in 1927. “As Mr. Buketoff recalled it,” read his obituary in the New York Times, “Rachmaninoff was unable to persuade Stokowski to adopt his preferred tempo for the last of the songs.”15 But it is not just that Plevitskaya and Rachmaninoff perform the song more slowly than Stokowski dared conduct it: Rachmaninoff plays with his patented, uniquely weighty ictus as in the first of the Symphonic Dances, and Plevitskaya’s half-parlando, half-yodeling delivery of what is after all a pretty drab and uninteresting melody is utterly inimitable. It is a really pungent taste of old Russia: the old Russia Igor Stravinsky once described as “a combination of caviar et merde.”16

And what, finally, is this extraordinarily caustic song about? Belílitsï and rumyánitsï are non-standard Russian words for feminine makeup: “face-whiteners” and “face-reddeners.” (The accents are indicated so that when listening to the song one can hear how, in the manner of all Russian folk singers, the stresses are shifted around at will in Plevitskaya’s performance, and in Rachmaninoff’s setting.) It is by now conventional to call the song what it was called on first publication of the recording, “Powder and Paint,” and the song portrays a woman frantically washing off her “face” at the approach of her husband, who is set on corporally punishing her for flirting with a bachelor at a party. Kurt Schindler (1882–1935), a German-born conductor who worked at the Metropolitan Opera and published many folk-song arrangements as well as a well-known anthology of Russian art songs, provided a translation of the text for Plevitskaya’s audiences in 1926, which although not entirely literal, preserves the rhythm of the original, as well as an appropriately archaic diction. As given here it has been slightly adapted for accuracy and pruned of its repetitions as well as the nonsense refrains (Ai, lyuli, lyushen’ki, etc.) with which Plevitskaya so alluringly embellishes it:

Quickly, quickly, from my cheeks, the powder off!

And the rosy paint remove without delay!

That my face be white and not betray the tale.

For I hear my jealous husband coming near.

Lo! he brings, he brings a costly gift to me!

What a gift, a precious woven whip of silk!

Ho! he longs, he longs to lash his little wife!

And I do not know nor guess the reason why.

For what evil have I done or what misdeed?

Only one offense that I can think of now:

To our neighbor’s feast I stole myself alone.

Opposite the bachelor they seated me.

To my handsome squire, a cup of mead I brought,

And with gracious smile, he took the foaming cup

Joining his white hands with mine upon its rim.

Then, before all folk, he call’d me “mistress mine.”

Hi! my mistress! Hi! My lovely little swan!

How I like thy graceful bearing and thy walk!

Quickly, quickly, from my cheeks, the powder off,

etc. 17

©Richard Taruskin, 2018

Richard Taruskin, the author of the Oxford History of Western Music, is Class of 1955 Professor of Music emeritus at University of California Berkeley and the recipient of the 2017 Kyoto Prize in Art and Philosophy.

1 Sergei Bertensson and Jay Leyda, Sergei Rachmaninoff: A Lifetime in Music (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), p. 361.

2 Bertensson and Leyda, p. 380, quoting the oral recollections of Yelena Konstantinovna Somova, the wife of Rachmaninoff’s friend and sometime secretary Yevgeniy Somov.

3 Charles O’Connell, The Other Side of the Record (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1947), pp. 167-68. 4 Barrie Martyn, Rachmaninoff: Composer, Pianist, Conductor (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 1990), pp. 348-49.

5 John K. Sherman, Minneapolis Star Tribune, 4 April 1943.

6 Alexander Pasternak, “Skryabin: Summer of 1903 and After,” trans. Felicity Ashbee and Irina Tidmarsh, Musical Times, CXIII, no. 1558 (Dec., 1972), 1169-74, at 1173.

7 Gunther Schuller: A Life in Pursuit of Music and Beauty (Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2011), p. 332. (In)

8 S. V. Rakhmaninov, Literaturnoye naslediye, III (Pis’ma) (Moscow: Sovetskiy Kompozitor, 1978), pp. 202-3.

9 Pitts Sanborn, New York World-Telegram, 8 January 1941.

10 Robert Pollak, Chicago Daily News, 7 November 1941; quoted in Bertensson and Leyda, p. 370. 11 Virgil Thomson, New York Herald Tribune, 22 December 1941.

11 Virgil Thomson, New York Herald Tribune, 22 December 1941.

12 Rachmaninoff to Joseph Yasser, 30 April 1935; S. V. Rakhmaninov, Literaturnoye naslediye, III: 49. 13 “Tagore on Russia: The ‘Circle of Russian Culture’ Challenges Some of His Statements,” New York Times, 15 January 1931.

14 Bertensson and Leyda, p. 247.

15 Allan Kozinn, “Igor Buketoff, 87, Conductor and Expert on Rachmaninoff,” New York Times, 11 September 2001.

16 Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Dialogues and a Diary (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1963), p. 224.

17 Kurt Schindler, trans., Ten Russian Folk Songs from the Repertoire of Nadiejda Plevitzkaia (1926); Maximilian M. Filonenko papers, Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European Culture, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University (first two stanzas quoted in Pamela A. Jordan, Stalin’s Singing Spy [Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016], p. 296n22).

Stalin’s Singing Spy follows the remarkable life of Nadezhda Plevitskaya, a Russian peasant girl who achieved fame as one of Tsar Nicholas II’s favorite singers and infamy as one of Stalin’s agents. Pamela A. Jordan traces Plevitskaya’s life from her childhood in an isolated village to national stardom. She always declared that she was foremost an artist who sang for all people, regardless of their ideological leanings or socioeconomic background. She claimed throughout her career to be fundamentally apolitical, yet decades later in Europe, Plevitskaya was unmasked as one of Joseph Stalin’s secret agents along with her husband, White Russian General Nikolai Skoblin. Their experiences in exile shed light on Stalin’s covert operations and the hardships Russian émigrés faced in interwar Europe, an era of great political and economic turmoil. In addition, this book uncovers the roles that the couple played in one of the Soviets’ major intelligence coups—the 1937 kidnapping of White Russian General Evgeny Miller in Paris. Jordan recreates Plevitskaya’s sensationalized 1938 criminal trial in the Palace of Justice, where she was accused of conspiring to kidnap Miller and portrayed as a Red femme fatale. The first Western biography of Plevitskaya and the first to reconstruct her dramatic trial, this book provides a fascinating window into Soviet-era espionage in interwar Europe.

RACHMANINOFF PLAYS SYMPHONIC DANCES

—A Musician’s Reaction—

Although I had listened to his studio recordings hundreds of times over the past decades, I was flabbergasted after my first hearing of the newly discovered recording of Rachmaninoff playing his Symphonic Dances. Immediately I thought of what Nicolas Medtner had written about his great friend and colleague’s playing of orchestral scores at the piano: “He played with such precision and astounding coloring it was better than any orchestra”. That is indeed the case here—it is nothing less than revelatory, on many levels. Rachmaninoff left a huge recorded legacy, but—as is well-known—forbade broadcasts of his live performances—just the opposite of his greatest pianistic contemporary (in Rachmaninoff’s own opinion) Josef Hofmann, who did not record much of his enormous repertoire and nothing commercially at all after 1923. Our chief impressions of Hofmann are through his broadcast legacy, which shows his playing in a different light from his records, in live concerts like quicksilver, his playing of any given work varying widely from concert to concert. Hofmann knew that studio recordings perpetuate interpretations of only a given moment in time, made in sterile circumstances. Certainly that is one of the reasons Hofmann refused to record his major repertoire for posterity.

There has always been this question about Rachmaninoff—was he the same pianist in concert as in the studio? Judging by many reports and the recordings presented here, the answer is probably “no”. We had all come to the conclusion that Rachmaninoff, speaking broadly, basically stuck to an interpretation once he decided upon it. But he himself wrote in 1934: “I am well aware that my playing varies from day to day. A pianist is the slave of acoustics. Only when I have played my first item, tested the acoustics of the hall, and felt the general atmosphere do I know in what mood I shall find myself at a recital. In a way this is unsatisfactory for me, but, artistically, it is perhaps a better thing never to be certain what one will do than to attain an unvarying level of performance that may easily develop into mere mechanical routine.”

Many, like my great teacher Jorge Bolet and several others who heard Rachmaninoff play works like the Chopin second sonata and Schumann’s Carnaval in the hall, said that his recordings, despite their greatness, gave only an impression of the freedom and color of those live performances. That can of course be said about many artists, perhaps the majority, who feel somewhat constricted by the microphone, knowing that what they leave behind, wrong notes and all, is for posterity. Schnabel’s Beethoven and Cortot’s Chopin are full of technical lapses, and even such a titanic musical and pianistic genius as Busoni suffered torments trying to record four presentable minutes of music.

Rachmaninoff was very much aware of the problems of recordings and for that reason made twenty takes for even such a short and relatively easy work as Mendelssohn’s “Spinning Song” and complained about the faults of some of his duo recordings with Kreisler. One can hear his liberation from the microphone on these CDs, along with the inimitable Rachmaninoff tone. But, perhaps the most important aspect of the recording presented here is the relationship of his playing to what is written. Mahler said “What is best in music is not to be found in the notes” and that is borne out here. There is much more rubato and agogic freedom in the phrasing in the composer’s realization at the keyboard than what one hears in almost any other recordings of Rachmaninoff’s works, except the recordings of conductors Golovanov, Mitropoulos and Stokowski. Such playing is far removed from most of today’s streamlined and “safe” performances, which avoid extremes of phrasing, subjective involvement and risk-taking. Bolet told me that he attended an early rehearsal of the Paganini Rhapsody with Rachmaninoff and Stokowski (1934), during which Rachmaninoff made several changes, all of which Bolet entered into his score, and showed me decades later. These included dynamics, tempi and even some notes.

Rachmaninoff was by all historical accounts no exception to this freer attitude towards his own music, opening the entire question as to what extent an Urtext should be considered bible-like and indeed what “playing what is written” even means. The greater the performer, the greater his or her subjective contribution will be. It is, after all, the sum of a unique personality and a lifetime of study and experience. Do any of the disciples of Mahler (Walter, Fried, Klemperer) sound even remotely like each other, indeed even like their own performances of the same works recorded years apart? Do Boult and Barbirolli, both friends of Elgar, conduct his works at all the same, indeed like Elgar’s own recordings? Do any of the Liszt pupils play Liszt alike? No! Indeed, if we had recordings of such stupendous geniuses as Mozart and Beethoven playing their own works, would that mean that is the way we must play them centuries later, on vastly different instruments in huge modern concert halls to a public otherwise used to listening to streamed music through earphones while riding the subway or working out in the gym etc.? How can we claim to know how to play composers from the 17th to 19th centuries based on historical texts, but do not always take seriously recordings from the composers themselves, or performers who studied with Liszt, Rubinstein and others? These are questions that no Urtext edition can answer. For me, it is this freedom with his own music (which he has in common with such dissimilar masters as Bartók and Stravinsky) and the great communicative energy with which he invests it is that mark the great value of this Rachmaninoff discovery, way and above the staggering pianistic and musical command demonstrated throughout.

©Ira Levin, 2018

Ira Levin studied with Jorge Bolet at the Curtis Institute of Music. He conducted Rachmaninoff’s operas, Aleko and the Miserly Knight, in 2013 at the Teatro Colón; 2014 saw the premiere of his orchestration of five Rachmaninoff solo piano works. Levin studies historic recordings extensively for clues about performance practice. His solo piano CDs of his own transcriptions of the music by Bach, Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and Villa-Lobos are especially notable additions to the recorded virtuoso literature.

A NOTE FROM THE PRODUCERS

The recording of Rachmaninoff, demonstrating how he wanted his Symphonic Dances to be performed immediately prior to its premiere, is a unique find. Unknown for decades it now takes its place near the summit of the world’s legacy of historic recordings. It documents what was possibly the composer’s second read-through of the score for conductor Eugene Ormandy, the eventual dedicatee of the piece, apparently at an informal gathering at which the composer translated his new orchestral score into a solo piano run-through, jumping from spot to spot and playing in an impromptu, non-linear fashion, “imitating the sound of the orchestra,” as Richard Taruskin’s notes describe the occasion. The composer’s first run-through for Ormandy had taken place at Rachmaninoff’s rented Huntington, Long Island, home during the third week of September 1940. Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra presented the world premiere on January 3, 1941. Specific details about a second run-through, however, remain hazy. We know that Rachmaninoff’s schedule was open all day on 21 December 1940, the date of the recording, and that Ormandy’s was open until evening, when he conducted at the Academy of Music, but we do not know the specific circumstances under which the recording was made. At least four distinct voices can be heard talking, laughing, and exclaiming on the recording. One sounds very much like Ormandy, one is an unidentified woman, and one is, presumably, the cigarette-scarred basso of the composer, speaking both Russian, English, and possibly German.

Many recordings of older, live musical performances (perhaps of less exalted status) have emerged in recent years from radio stations and other sources. No longer rare and unusual, they are now ubiquitous “historic” aural snapshots of music as it was actually made back then. They confirm that live music was often played in a different way from today—in a word, it was freer. Further, comparing historic live recordings with the corpus of commercial recordings of the same period suggests, also, that the commercial recording process itself seems to have inhibited musicians. The prospect of leaving an imperishable legacy has sobered many musicians into an almost frightened state when recording for posterity, causing them to play carefully and correctly—but not freely. That phenomenon of deliberate restraint associated with making recordings persists to this day, but it is only a concomitant part of the much larger, general tendency toward impersonal literalness in playing music, helping fuel the onrush of history that has taken musical performance ever further from spontaneity.

Whether this matters is debatable, for although current performances and recordings (and older commercial recordings) might show less personal imagination, modern performances are undeniably more acceptable to most modern ears. There are many folks for whom historical recordings of actual performances often seem comical. We know from existing recordings of Bartók, and especially Prokofiev, that few if any current performers play the way the composers do on those recordings. Today’s students often find Prokofiev’s playing of his own piano works shockingly romantic, unsuitable as guides for how they should play Prokofiev. The way any important composer played their own music on a recording is evidence of how the music might be played, but can we, should we, play that way now? If not, how do we put the evidence captured on historical recordings into the broader context of correct performance practice? The idea of recapturing “what the composer intended” has emerged as a philosophical exercise that is often used to justify purely modern trends, but it seems also an exercise with an unconscious agenda: to find every scrap of evidence to support modern ideas of performance practice, but to ignore other evidence. So far no way has been found to incorporate any lessons that might be learned from historic recordings into modern performance practice, but that does not mean we should ignore these recordings.

Rachmaninoff once described his recording sessions as highly stressful ordeals. There is an important question that has never been resolved—how well do his recordings actually represent his live playing? Received opinion on the subject coalesced long ago around the idea that the composer/pianist’s commercial recordings accurately preserved his final, unalterable thoughts on performance. Two knowledgeable connoisseurs who often heard Rachmaninoff in concert and were intimately familiar with his recordings, Harold Schonberg and Abram Chasins, both stated this view forthrightly in their books. Yet Vladimir Horowitz averred in a taped interview with Schonberg that, of all the Rachmaninoff commercial discs, only the recording of his First Piano Concerto, and in that only in the second movement, provides an accurate glimpse of the penetrating intensity, spontaneity, and tonal luminosity of Rachmaninoff on the concert platform.

Rachmaninoff was punctilious at the Victor record company, insisting his rejected takes be destroyed; had he known this recording was being made, he would likely have insisted upon its destruction after it had served its purpose. For whatever reason it was not destroyed. Rumors of live Rachmaninoff recordings were diligently investigated through the decades, but all turned out to be chimeras, so it was more than astonishing when this recording came to light. It had been hiding in plain sight in the University of Pennsylvania’s Eugene Ormandy Music & Media Center. When Ormandy died in 1986, his collection was given to the University. Years later, composer Jay Reise, a member of the University’s faculty, noticed a catalogue entry for an item in the Ormandy collection, on two ten-inch double-sided aluminum based, lacquer coated discs: “33 1/3; 12/21/40; Symphonic Dances … Rachmaninoff; Rachmaninoff in person playing the piano” the information copied from the typewritten record labels. Professor Reise, personally much interested in both the music of Rachmaninoff and the playing of historic pianists, brought the recording to the attention of Ward Marston. Reise had immediately realized the importance of the recording, for apart from the evidence it contains about the composer’s wishes concerning performance of the score, the discs captured Rachmaninoff’s “live” playing. Time will tell whether the recording settles any questions about his live versus commercially recorded playing.

There are other home-made acetate discs in the Eugene Ormandy collection, poorly-recorded broadcasts that the conductor apparently wanted saved, but nothing else like the Rachmaninoff recording. It is possible, but not probable, that Alexander “Sascha” Greiner, then the manager of the artist relations department of the Steinway piano firm, could have been involved. Greiner, a friend of Rachmaninoff’s, owned a home disc-recorder, quite uncommon at the time, which he could operate competently. Using it, he had recorded the informal recordings of Bublichki and Polka Italienne, included in this collection.

In addition to the extraordinary playing of Rachmaninoff himself, to provide context we have selected recordings of late-period Rachmaninoff compositions, performed by musicians who were personally associated with and coached by the composer. We have included two versions of Rachmaninoff’s recording: a complete transcription as it was recorded (CD 3, Tracks 6–9) and an edited version in musical sequence with all repeated passages and spoken comments omitted (CD 1, Tracks 1–6).

Rachmaninoff was of two minds regarding the idea of definitive performances. He was content with scrupulous adherence to the score, always expecting professional competence as the minimum. He might disagree with conductors and insist his own view prevail, as with Mitropoulos’s initial tempo at the beginning of Symphonic Dances. Rachmaninoff’s occasional dust-ups during rehearsals with conductors Furtwängler, Mahler, Reiner, and Stokowski, reportedly laced with Russian curses, invariably resulted in magical performances. But there were some musicians he held in such high regard that he ultimately accepted almost anything their creative imaginations might uncover in his music. Dimitri Mitropoulos, Benno Moiseiwitsch, and Leopold Stokowski were foremost among these, as well as Feodor Chaliapin, Nikolai Golovanov, Josef Hofmann, Nina Koshetz, Willem Mengelberg, and Antonia Nezhdanova. (Vladimir Horowitz was another, more complicated, matter.)

This recording of Rachmaninoff’s impromptu playing will probably remain the only document of its kind, an important archaeological artifact to be studied and treasured. It gives us a unique peek into the mind of a great composer and pianist.

‘Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances’ Review: A Master Interprets Himself [pdf]

Sergei Rachmaninoff was notorious for refusing to have his performances recorded, but the discovery of one in a university archive presents his music in an entirely fresh, overpowering way.

—Joseph Horowitz, Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2018

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) Rachmaninoff plays Symphonic Dances: Newly Discovered 1940 Recordings [pdf]

Marston’s documentation, a thirty-one page book in English, is second-to-none. Richard Taruskin’s extended essay provides more than adequate background and context, whilst Ira Levin views things from a musician’s perspective. There’s also a detailed note from the producers. This set is of notable historical importance and it gets my warmest recommendation.

—Stephen Greenbank, MusicWeb International

Rachmaninov desencadenado [pdf]

El valor del documento es incalculable y la edición de Marston Records es un justo homenaje a la mejor composición de Rachmaninov

—Pablo L. Rodríguez, Scherzo, November 2018

“Nobody Could See This Coming”: Marston Records’ Revelatory Rachmaninoff Release [pdf]

This is, quite simply, the most important, and most arresting, historical release of the century, something that no lover of Rachmaninoff (as composer or pianist) or of piano music more generally can let slip by. It would be a top priority even if the sources were not so artfully restored, and it would be so even if it came in plain brown wrappers.

—Peter J. Rabinowitz, Fanfare, Jan/Feb 2019

Rachmaninoff’s Private Concert at Eugene Ormandy’s House in Philly Is Now Yours to Hear, 78 Years Later [pdf]

—David Patrick Stearns, Philadelphia Inquirer, August 2019